‘That film ruined her life’: Maria Schneider and the sordid legacy of Last Tango in Paris

On October 15 1972, the French actress Maria Schneider awoke to find herself the most talked-about woman in America. The film in which she starred, Last Tango in Paris, had premiered at the New York Film Festival the previous night, and had become immediately notorious.

Its distributors United Artists – experts in whipping up controversy after previous experience with the Oscar-winning, X-rated prostitution drama Midnight Cowboy – had held no press screenings but let it be known that there were scenes in Bernardo Bertolucci’s new picture that pushed the sexual envelope beyond what audiences had ever expected in mainstream cinema. No wonder tickets were selling to the curious, or prurient, for $100 apiece.

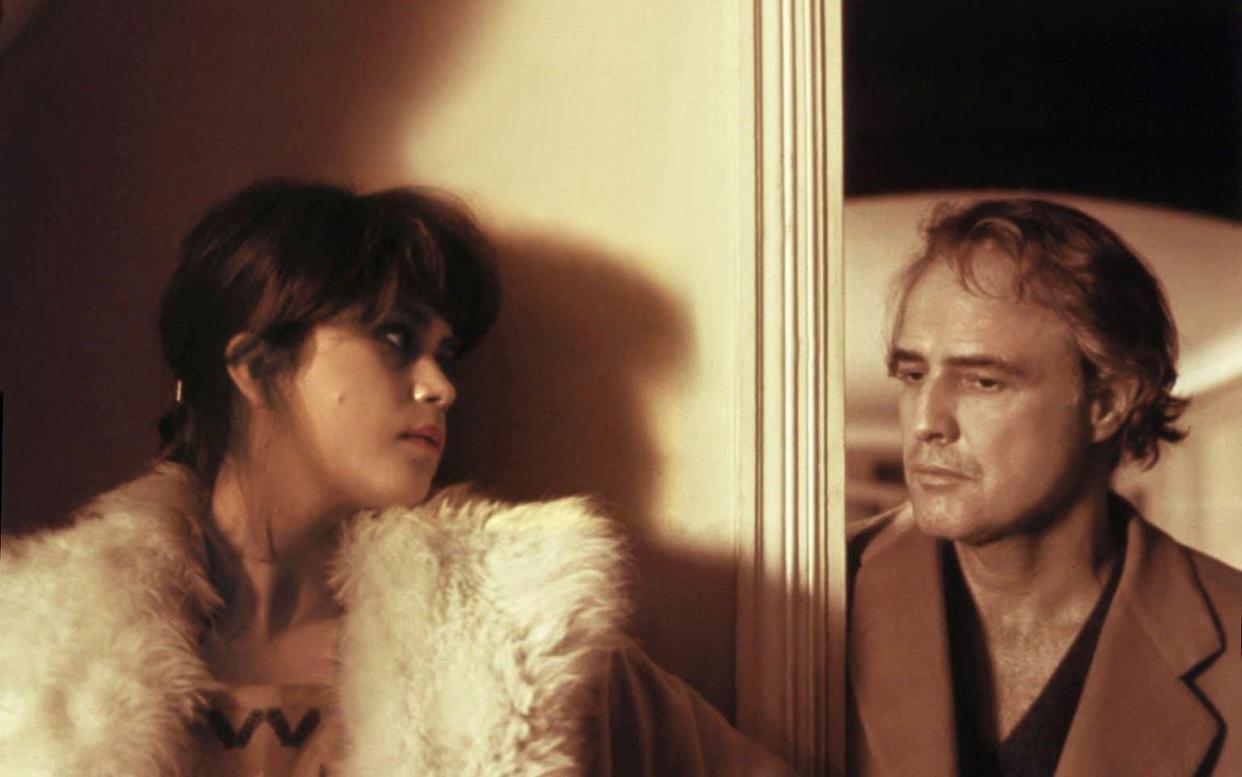

The events that led up to the premiere of Last Tango in Paris, and Schneider’s reluctant involvement in the film’s most notorious moment – a butter-assisted depiction of sodomy between Schneider and the film’s star Marlon Brando which, increasingly, looks like a rape scene rather than a love scene – have now been made into a film, Being Maria, which has premiered at the Cannes Film Festival.

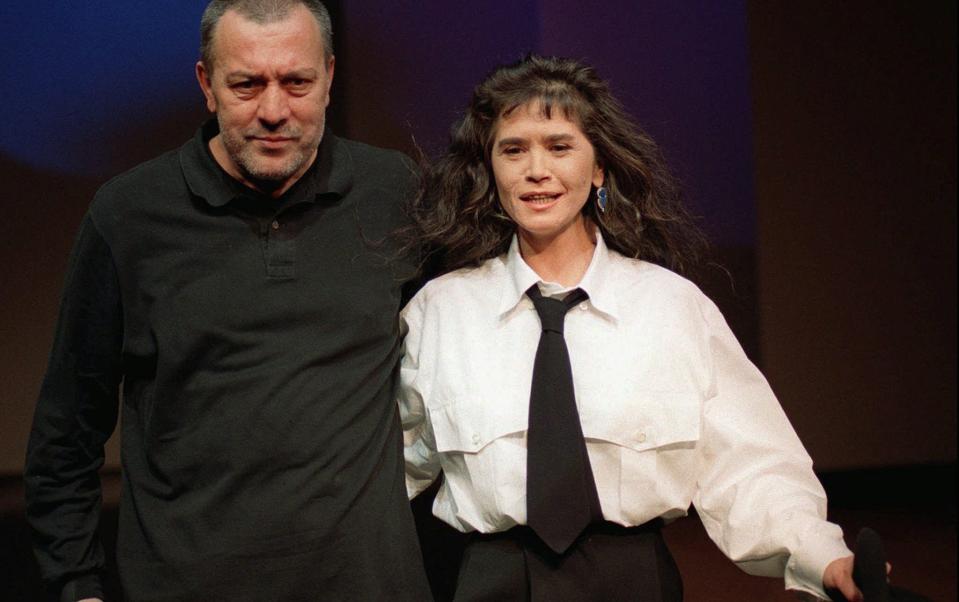

Starring Anamaria Vartolomei as Schneider, alongside Matt Dillon as Brando, the immediate critical consensus is that the film is stronger when it concentrates on the events during and immediately after the production of Last Tango in Paris than depicting the remainder of Schneider’s tragic and frustrated life. She continued to act until her death in 2011, at the age of 58, but seldom with the same impact as her most famous role.

There were rumours throughout Schneider’s career that she was “difficult” – the kiss of death when it comes to a sustainable professional life, especially when an actress is no longer marketable as an ingenue. Although the success of her most famous film led to her being offered a variety of high-profile roles, the hurt and humiliation that she underwent at the hands of both Bertolucci and Brando – for which she received a considerably lower salary than either of those two men, who made millions when it became a box office sensation – drove her into heroin addiction and suicide attempts. The picture that made her famous became the ultimate poisoned chalice: as one friend of hers, Esther Anderson, said: “That film ruined her life.”

At the beginning of 1971, Bertolucci was keen to exploit the success that he had had with his earlier films, including The Conformist and The Spider’s Stratagem, which were about, respectively, the descent of a diffident man into politically motivated assassination and a character’s inability to escape the legacy of his antifascist martyr father. Both pictures featured intense performances from their male protagonists, a dreamlike atmosphere and moments of shocking violence, all of which can be found in Last Tango in Paris, but the new film would push the envelope considerably further than its predecessors.

The director was only in his early 30s, but he was already a filmmaker of considerable note, and actors were keen to work with him. Marlon Brando, then riding high after his performance in The Godfather, was not Bertolucci’s first choice for the lead role in his new film. His initial plan for the casting was to reunite his lead actors from The Conformist, Jean-Louis Trintignant and Dominique Sanda, but Trintignant was, in Bertolucci’s words, “beyond shyness” and informed the director, nearly in tears, that he could not be “à poil”, or naked, on screen.

Sanda was pregnant, so she was ruled out, and Bertolucci went to the two European leading men of the moment, Jean-Paul Belmondo and Alain Delon. Belmondo found the script offensive and, in Bertolucci’s words, “a piece of obscenity”, and Delon would only agree to take on the role if he could also serve as a producer, something that the director peremptorily refused. Then, quite by chance, Bertolucci was in Rome having dinner with the Italian head of Paramount, who was raving about Brando’s performance in The Godfather, and the director thought “yeah, that’s the one”.

Schneider, however, was cast in more roundabout circumstances. Bertolucci offered the role to the European actress of the moment, Catherine Deneuve – perhaps with the memory of her performance in Belle de Jour in mind – and she initially accepted, only to back out when she discovered that she was pregnant.

The then-19 year old Schneider had not yet taken on a lead role, let alone one that would be as demanding as the part of Jeanne, a young Parisian woman who meets Brando’s middle-aged widower Paul in an anonymous apartment for equally anonymous bouts of sex. She was the estranged daughter of a well-known French actor, Daniel Gelin, and said later that “Even before my experiences on Last Tango, I found it hard to trust men. I only met my father when I was 15 and all the role models in my family were women.” Her experiences on the film would only strengthen this distrust.

Although it is easy to see why an ambitious actress would wish to take on a potentially star-making role, there was something distasteful and exploitative about the project from its inception. Bertolucci was open about writing a script based on his own erotic fantasies, and he spent a good deal of time with Brando finessing the actor’s part to his own specifications. The director encouraged Brando to turn the role into an extension of himself. Brando later wrote in his memoir: “Bernardo tailored the story to his actors. He wanted me to play myself, to improvise completely and portray Paul as if he were an autobiographical mirror of me… he had me write virtually all my scenes and dialogue.”

Schneider was given no such indulgence. She was simply “the girl”, and given minimal direction. Although she later claimed in a 2007 interview to be relaxed about the film’s envelope-pushing sexual content – “nudity wasn’t a problem for me in those days as I thought it was beautiful” – she was aghast when Bertolucci suggested that she and Brando have sex for real on set, in order to improve the film’s level of authenticity. Brando, thankfully, refused, on the grounds that “it would have completely changed the picture and made our sex organs the focus of the story.”

But working with the director was an unpleasant experience at the best of times. As Schneider recounted later, Bertolucci was “fat and sweaty and very manipulative, both of Marlon and myself, and would do certain things to get a reaction from me. Some mornings on set he would be very nice and say hello and on other days, he wouldn’t say anything at all.”

Yet the worst was yet to come. The centrepiece sex scene was not in the script that she signed up for, and instead came about as an idea – some would call it a fantasy – of Brando’s. Schneider was angry about having to perform it, saying that she was only told about it moments before shooting took place and that “I should have called my agent or had my lawyer come to the set because you can’t force someone to do something that isn’t in the script, but at the time, I didn’t know that.”

Brando did his best to console her during the filming of the exploitative – and still hard to watch – scene by saying “Maria, don’t worry, it’s only a movie”. But Schneider wept uncontrollably during filming; the tears on screen are entirely genuine. After it finished, she felt “humiliated and to be honest, I felt a little raped, both by Marlon and by Bertolucci. After the scene, Marlon didn’t console me or apologise. Thankfully, there was just one take.” Bertolucci was unrepentant, saying later: “I wanted her reaction as a girl, not as an actress. I wanted her to react humiliated.”

When Schneider eventually attended the film’s premiere, she had not yet seen the picture, and her reaction was a visceral one. Esther Anderson, who was with her, later recalled that “she was absolutely shocked. She had no idea what they were going to do with her. She ran from the cinema screaming and I had to run after her into the street and comfort her.”

Matters soon worsened. There was an Italian private prosecution by Gino Paolo Latin, the prosecutor of Bologna, on the grounds of “obscene content offensive to public decency” and “descriptions and exhibitions of masturbation, libidinous acts and lewd nudity, accompanied off-screen by sounds, sighs and shrieks of climatic pleasure”. It was initially unsuccessful, but, in September 1973, the appellate court in Bologna sentenced Bertolucci, Brando and Schneier to two months in prison and a fine: this was later overturned in December that year by the country’s highest court, the Court of Cassation.

Nonetheless, it was clear that the film had caused grievous offence in Bertolucci’s home country, and the stress drove Schneider to extreme lengths. She later said in an interview that the controversy “made me go mad. I got into drugs – pot and then cocaine, LSD and heroin – it was like an escape from reality.... I didn’t enjoy being famous at all, and drugs were my escape. I took pills to try and commit suicide, but I survived because God decided it wasn’t the time for me to go.”

That she was openly bisexual did not help her newly acquired reputation as libidinous, even if she now made a point of rejecting any roles that required nudity. She appeared opposite Jack Nicholson in Michelangelo Antonioni’s existential classic The Passenger in 1975, but apart from that, struggled to escape from the considerable shadow of Last Tango throughout the rest of her life and career.

Today, everyone from Martin Scorsese to Brad Pitt has praised Brando’s performance in the picture, with Scorsese describing the role as “the purest poetry imaginable, in dynamic motion”. Pitt, meanwhile, has said it is the part that he would most have liked to play, remarking: “Brando. That one hurts.” Schneider has been comparatively ignored, something that Being Maria is now, belatedly, addressing.

There had been a previous attempt at filming her experiences on the film in a planned 2021 miniseries, to be written by Jeremy Miller and Daniel Cohn, and one of the directors intended for the project, José Padilha, said “Tango tells the story of two men abusing a young and unexperienced woman, not for sex, but for the sake of art. They did it on camera, and the resulting scene made it into a major feature film, acclaimed by critics and audiences alike. The director and the actors basked in success, while Maria’s pain was neglected.” The series did not come to fruition but now, finally, viewers will know the truth.

It may have come as some consolation to her that Hollywood united against Bertolucci in later years. He is now, with some justification, seen as less an auteur and more a dirty old man, and as Jessica Chastain said of Last Tango, “To all the people that love this film – you’re watching a 19 yr. old get raped by a 48 yr. old man. The director planned her attack”.

Later in life, Schneider happened to be at a film festival years later that Bertolucci was also present at. The organisers tried to bring about an impromptu reunion between director and star, but she refused. “I don’t know that man,” she said.