The Fire Behind The Film: ‘Bob Marley: One Love’

When movies come out, we grade them with reviews, define them by box office returns or eyeballs on streaming services, and maybe trophies down the line. But every successful, ambitious film starts with a dream, followed by compromise and adversity. Here begins Deadline’s occasional peek into the creative aspirations, and the sweat and blood that propels ambitious films.

The Movie

Bob Marley: One Love

More from Deadline

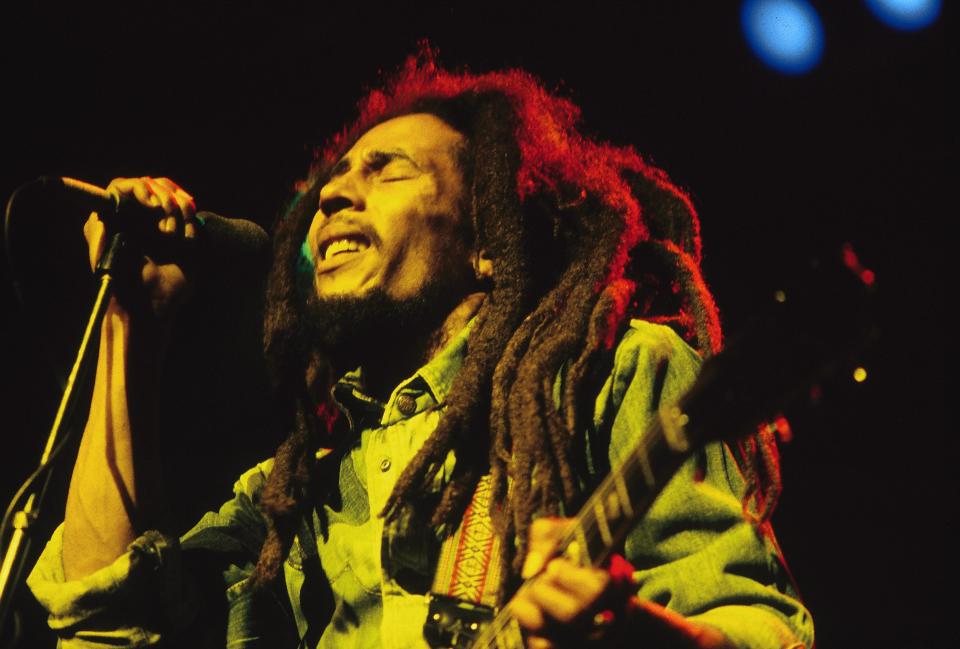

In today’s challenged theatrical marketplace, it’s particularly pleasing when a plan works out. Slotted against an underperforming Madame Web for President’s Day weekend, Paramount Pictures’ Bob Marley: One Love on Wednesday set the Valentine’s Day opening record with a $14 million gross, and the film has a nice chance to eclipse the initial $30 million long weekend projections. Per Rotten Tomatoes, the Paramount film has pleased audiences (95% approval) more than critics (44%), but Reinaldo Marcus Green’s skillfully made biopic of an iconic artist brought to life in a breakthrough acting turn by Kingsley Ben-Adir is a potent combination, especially when draped in Marley’s gorgeous and universally known reggae hits.

The History

Try about 20 years worth of futile attempts that never got to the starting line. One had the singer’s daughter-in-law, Fugees’ singer Lauryn Hill, one had Marley’s Grammy-winning son Ziggy playing the lead; there were rumors about Lenny Kravitz; and filmmakers including Martin Scorsese and Jonathan Demme circled Marley movies including a 2012 documentary eventually directed by Kevin MacDonald. Rights for a narrative project migrated to Paramount, but nothing happened until Mike Ireland and Daria Cercek became co-heads of the Motion Picture Group.

“The music rights came with the life rights; there was a blanket license that allowed us to access the vast majority of the catalog,” Ireland said. “The ones we didn’t have were easy enough to get, especially when it’s Ziggy Marley knocking on a rights holder’s door. We came in late 2020 and you evaluate what’s in the cupboard, and both Daria and I pointed to this one and said, oh, this is one we’re going to make. We had to re-up the rights and renegotiate this or that, but from that moment, it quickly took on a different life and a different urgency.”

Marley’s son Ziggy said the difference between this attempt and others was a decision by the family to take the initiative.

“Over the years there have been a few attempts, but what happened here is that we were the instigators of it,” he said. “The family took the step to approach people instead of waiting for them to come to us. We helped choose directors, producers actors, so the family became the real force behind this instead of the force coming from somewhere else, which was what it used to be like.”

There have been movies where subjects’ influence led to intrusiveness into the creative process. Who wants to put the Marley music catalog on display with a filmed depiction that might hurt sales? By all accounts, that didn’t happen here. There are depictions of a marriage between Bob and Rita Marley where each was unfaithful, for instance, and Marley is far from perfect but he sure is likeable.

“We wanted to show a side of Bob that is not seen in interviews, or anything people already know,” Ziggy Marley said. “We wanted to really show the internal struggles and the emotional side of Bob much more than anything has ever shown us before. People knew a lot of things, so we decided it was the internal workings around the emotional side. He was not a one note person, and we wanted to make sure that he was represented. We were there on the set, every day, myself and Neville Garrick, who worked with my father.”

The Vision

Coming off King Richard, the underdog story of Serena and Venus William that resulted in a Best Actor Oscar for Will Smith’s portrayal of the patriarchal title character, Green proved he could tackle cultural icons in lockstep with a family safeguarding a legacy. “When I first spoke with Rei, we had an early version of the script [Terence Winter, Frank E. Flowers & Zach Baylin share screen credit with Green] and first thing he said that struck me was this is a man who will speak the truth, but was somebody who could work with us,” Ziggy Marley said. “That was very important for us because we wanted to always be involved. Reinaldo brought so much to the table, and I respected his work, too.”

They’d focused on a pivotal moment in Marley’s life. As Jamaica roiled in a power struggle that began when it ceased being a British colony years earlier, Marley was far and away Jamaica’s most influential voice even though he was not a political figure beyond the lyrics of his culturally relevant songs. After he announced a Smile Jamaica concert, Marley was targeted for assassination; his wife Rita was shot in the head and nearly killed and Marley was hit in the wrist. He performed in front of 80,000 days later – Rita got out of a hospital bed to sing backup – but Marley left his home country for London while Rita took their kids to Miami, for safety reasons. The infusion of punk movers like The Clash, fame and women in London, had good and bad influences on the artist. He had been disowned as a youth by his father; adding that to his exile from Jamaica and separation from wife and children, Marley was searching for his own place of belonging. All of these images swirl as Marley and the Wailers record the seminal album Exodus and plot a return home and a reunion with his family. Why did the Marley clan embrace him?

“I hope it’s the humanistic approach to my filmmaking,” said Green, who was surprised when Ziggy told him how much he appreciated Stone Cars, a no-money student film Green directed at NYU, which had some parallel underclass themes. Green also had learned much about collaboration coming off King Richard, like when to hold your serve, and when to be changeable and factor in the family’s input that added authenticity.

“A lot of it was the communication process,” Green said. “And because they’re not filmmakers, it’s just the language and in in the way we talk about film. I was able to always make it about the movie and not about the personal. So for instance, if something happens in a particular location that may not be cinematic, how can we create a cinematic experience that is still truthful? King Richard, it was no different. For instance, the scene that happened on the tennis court with Will and his daughter, it was originally scripted to be in the bedroom, and she was crying with a doll. And that’s not cinematic. It’s much more cinematic if she’s outside and they’re on the tennis court and it ties in. It’s visually about communicating how we can still tell the truth or a form of the truth through visual storytelling. We have two hours to tell a story about your dad. It is impossible to get everything in there. We have to shape this in movie language, and that includes score. When do we use your dad’s music versus when we’re going to use score to elevate a particular moment cinematically? That’s always a tricky thing when you’re glued. But they were very receptive to the idea that we were making a movie together. And it just comes down to communication. It’s like any quarterback, right? You’ve got your fullback wide receivers, you’ve got all your personnel, and you’re just trying to get the ball downfield and in the end zone, and by any means necessary, how do we win the game?”

That included a resolution with Marley’s would-be assassin, which is in the film but didn’t happen, and the depiction of Marley’s London adventures, each of which served truthful themes in the film. “That comes down again to movie-making language,” Green said. “I think forgiveness can be portrayed a lot of different ways. I think it would be doubtful after what happened early on that anybody would be able to walk into a house without being seen or caught in reality, but Bob’s forgiveness to this represents a larger forgiveness. He forgave Jamaica, he forgave everything that happened. So that moment represents so much more than the individual. And so that’s a cinematic way to show it in our film. Obviously we took liberties there, but I think it represents the truth. That’s the best way I can explain it.” He wanted to include London and Marley seeing The Clash, as famed for punk rock as Marley and the Wailers were for reggae.

“It’s context and place and time and where are we,” Green said. “The Clash was influential not only to Bob, but to many others, and I think there were a lot of similarities between punk rock and reggae in terms of its anti-establishment and anti-colonialism themes, that put them on the fringes of society. They were seen as the bottom rung and they rebelled against that with reggae’s rebel music. So that all kind of represented that in a fun and exciting way. And a lot of people remember The Clash in ’77 and that Bob had gone and seen them. I thought it was a good way to establish where we were a place in time, but also get some political context and context of where we were in our timeline.”

The Performance

Green wasn’t the only one coming off a job that would help on the difficult task of channeling Bob Marley. Ben-Adir disappeared into Malcolm X in the Regina King-directed One Night in Miami. But he was a strong physical match there, and he’s about a foot taller than was Marley. So he didn’t imagine he’d get far when he sent an audition tape. Still, he had something. I recall director John Woo and Martin Scorsese tell me that when they projected their best selves into their screen characters, their avatars were Chow Yun Fat and Robert De Niro. Ben-Adir held the promise of presenting a most cinematic rendering of the diminutive Marley, and what he lacked in musicianship he more than made up for in acting chops.

“Kingsley, he kept us engaged,” said Ziggy Marley. “We looked at a lot of tapes, but Kingsley just kept us engaged with the connection he established with the character.” Said Green: “It took a year to find Kingsley. We looked at every tape we possibly could, from every country we possibly could, including Jamaica. We looked at family members.” Whereas once Ziggy Marley was a possibility, that ship had sailed. “Bob died at 36 and Ziggy’s 54, and looks great, but I needed a younger man. Lenny Kravitz is amazing but he wouldn’t have been right either. They’re famous musicians, it takes you out of the movie, and away from that movie language I mentioned. What we needed was an actor who could disappear and in some moments leave you feeling you were watching Bob Marley.”

That happened to Green when he watched the actor’s audition tape and had the “who’s that” reaction. He’d seen One Night in Miami, but because Ben-Adir’s hair was short, did not recognize the actor he was now watching. “Kingsley could just disappear, and there were moments I’m thinking I’m watching Bob. I felt the same as when I watched Spike Lee’s Malcolm X and forgot it’s Denzel and felt I was watching Malcolm. I know it’s a movie, but that’s how good he was in that film. We sought to create something similar with Kingsley where you’d just forget and feel you are watching Bob because the story and the music, it’s all so good. Credit to Kingsley, I can’t make him lose 40 pounds, teach himself not just a genetic patois language, but one that is specific to Marley. Or learn how to play guitar, how to sing and dance, and understand the significance of the words he is singing.”

Ben-Adir said his onstage performances was an example of inhaling all the mythology of a legend, and throwing himself into it and “having a go.” Having played Malcolm X helped him in the biggest challenge here, which he said was finding a handle on a layered and complicated subject. “I think you go straight to the vulnerability,” he said. “With Malcolm, I leaned on a lot of what Dick Gregory wrote about him, because I didn’t have access to the family. For Bob, I spoke to tens of tens of people, family and friends and bandmembers who were with him at the time. Every scene became an opportunity to try and investigate his spirit. The way I work is that it’s a bottomless pit of ideas, and the best idea wins. Being the size I am and Bob being very physically different, at some stage I just had to let go of feeling like I needed to look as similar as I could to him, and just trust in focusing on the authenticity of the language and how Bob engaged with music.”

There, he found the North Star that gave him the handle on his performance as Marley. “What the music meant to Bob specifically, I think he found real safety in music and I think it saved him, Ben-Adir said. “Honing in on that, and what it means to create music on that level … I learned how to play guitar and sing because I wanted to understand what it meant to have a relationship with an instrument and to write songs, which Bob did every day.

“I wanted to find out what Bob’s experience was as a child all the way through so that I could kind of try and connect to him on some kind of psychological level that made sense for a through line, so everyone could relate to him. What became most apparent with Bob in the context of this film was his relationship to safety and this journey that he went on to spread a message of peace and love and unity through his music. A lot of Bob’s vulnerability in his spirit, it is all in his music. He was a poet and he was a genius. But the real question for me was, where was Bob with himself in terms of his sense of safety? A lot of conversations I had with his friends and his family were just really me trying to check in with him on that level.

“He was going through a lot. And I did find out that recording the Exodus album after the attempted assassination was a very, very intense period of time for all of them. It was very, very work focused. Bob had a drive in him, and I don’t think it’s a coincidence that he created one of the great albums, weeks after he nearly died. Bob’s sense of a man’s lifelong journey to find inner peace was the internal through line that I latched onto after spending months and months and months talking to his family and his friends, and then reading the script and saying, you know what, if this is some sort of redemption story internally, that’s what I’m going to lean on. Finding Bob on a really, really internal level as it related to safety, to me felt universal for the audience because we’re all on our own journeys to try and find a sense of togetherness and a sense of love. We all want to feel connected and we all want to feel seen and heard and cherished in some way. I had to really understand what my relationship to that was. So the movie to me was about safety and finding Bob on his lifelong journey to find inner peace. But you can’t spread peace unless you are in some way trying to find it for yourself as well.”

The Payoff

The early results indicate the years of work were well worth it. Worldwide gross today is $19.4 million, including the first 10 markets, with 26 more following. It was paramount to all that Jamaica’s greatest export be embraced at home, and Bob Marley: One Love opened yesterday at $100,000, with an 89% audience share. That put the film past Black Panther, the previous record holder in Jamaica.

From the standpoint of a studio where every green light decision is perilous, Bob Marley: One Love already falls into the win column.

“We talk often about trying to find big commercial movies for adults,” said Paramount’s Ireland. “It seems reductive and simplistic to say, but there’s not a lot of it. And it feels like to some degree, that’s an underserved market, when you have this connection to music that has a global reach, and a really strong script and a filmmaker coming off a multi Oscar-nominated movie, and a rising star. It cost $70 million, all in.”

All of the participants said their measure of success came down to the reaction of Rita Marley, played so skillfully in the film by Lashana Lynch. Rita met Marley when both were little more than children, and it was she who took that life journey with him from rags to riches, and who has continued to keep his memory alive.

“I sat behind Rita when it premiered in Jamaica,” Ben-Adir said. “She was very emotional through the screening, and it was really hard. But her family surrounded her and we’re hugging her and just making sure she was okay. Rohan has, on a number of occasions, have spoken to me about his feelings about just the essence of finding his dad’s voice, his dad’s spirit, in moments. And yeah, that was goal, really. To find Bob’s voice and the authenticity of how he spoke and the vulnerability and the humanity of him. That was what I was working towards in trying to convince Jamaica and the family and anyone else I could do this.”

Paramount’s Ireland fixed on several moments: “We did a series of pre-records in advance of shooting the movie. We had a lot of the original masters available to us, but a lot were either damaged or it was from a mic on the left side of the stage that picked up more cymbal than it did Bob. So you had to kind of put together a version of each song that made sense. And in that prerecorded session, Kingsley was there and he was studying concert footage of Bob, and he was trying to mirror his movements while also he couldn’t play a single chord in the guitar. And just what I saw in him was this focus that usually in my brain is reserved for athletes. He was so intense and the magic of that moment with him doing that, as Ziggy and Steven are over here singing their father’s songs … there was just something in the air, and you kind of knew at this moment if you didn’t understand it before, the gravity of the thing that you were about to undertake. And it was just … I won’t forget it. I just won’t forget it. One of those moments where you look up and realize that you are part of a magical machine.

“The other thing seared into my brain forever came at the premiere in Kingston,” he said. “There were two things. The second that Kingsley said his first line, the audience applauded because they knew we didn’t screw it up. They were very afraid of the Hollywood whitewashed version of the story. And they knew we didn’t mess it up, as they applauded on the first line. Also, Rita Marley was there. Rita Marley is in a wheelchair. Rita Marley cannot speak. And at these incredibly emotional moments in the movie when Rita’s shot, when Bob is with her in the hospital, when Bob announces he has cancer … the theater was quiet, save for this audible wail going up in the back of the theater. It was Rita, because the movie is transporting her back in time to those moments. And she’s feeling all of that again. And that to me is the ultimate validation of the thing that we did. It just, that’s kind of the ultimate vote of confidence.”

Best of Deadline

Sign up for Deadline's Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.

Solve the daily Crossword