First Americans Museum connecting Smithsonian's tribal objects and Oklahoma Native families

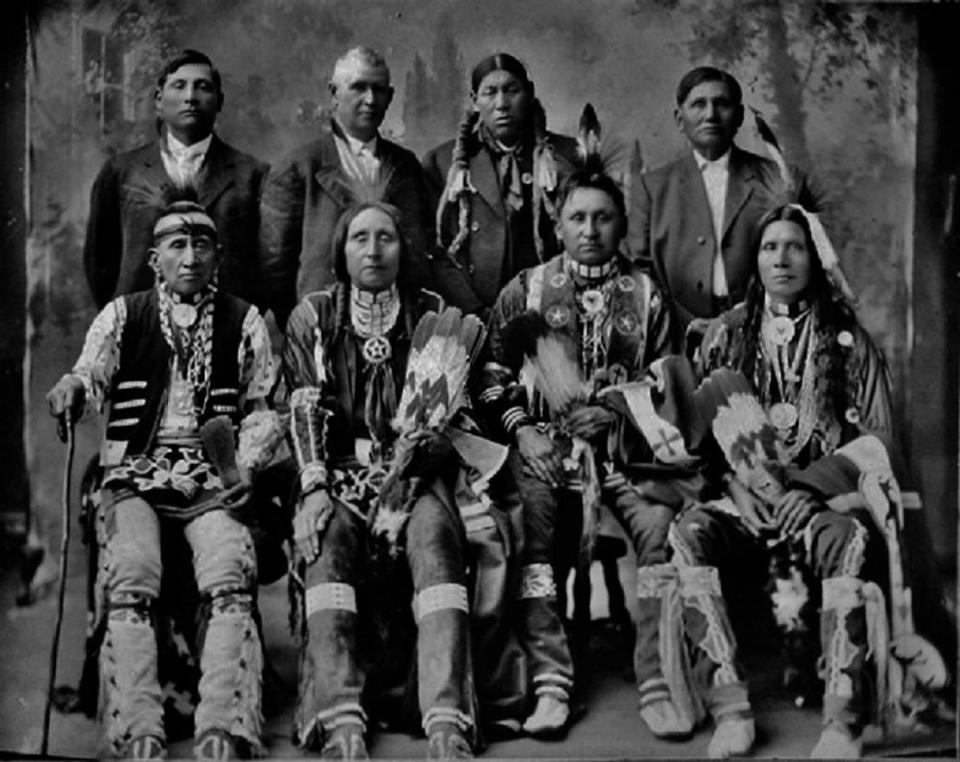

Everywhere James Pepper Henry has lived, the same black-and-white photograph has been displayed: a portrait of Kaw Nation delegates who traveled to Washington, D.C., in 1909, including his great-grandfather, James Pepper, or Mokompah, meaning "Medicine Powder."

"I've had this picture hanging on my wall my whole life," said Pepper Henry, pointing to the man sitting in the bottom row, second from the left, in the digital version of the photo he now keeps on his cellphone, too.

"This gentleman right here is my great-grandfather ... and sitting next to him is a man named Mehojah, which means 'Gray Blanket.'"

As Pepper Henry was interning in the 1990s at the fledgling National Museum of the American Indian in New York, he was looking through the Kaw items in the Smithsonian Institution's collection when he saw the name "Mehojah" on one of the drawer labels.

"I opened the drawer, and I saw this otter collar ... that is being worn by Mehojah in that historic photograph. And that's what has inspired me," Pepper Henry said. "I got so excited, I called the grandson of Mehojah ... and I told him about the otter collar. And it made me realize, at that moment, that thousands of objects were in the museum (collection), and each one of them had a story and had a family that they were connected to."

Not only did he get to reunite the fur collar with Mehojah's grandson, William Mehojah, but he also is proud to exhibit it now at Oklahoma City's First Americans Museum, where Pepper Henry is the director and CEO.

Mehojah's otter collar is part of the OKC museum's exhibition "WINIKO: Life of an Object," which features about 140 items on long-term loan from the Smithsonian's National Museum of the American Indian. The objects were bought in the early 1900s from members of the 39 Native American tribes now headquartered in Oklahoma, and curators at First Americans Museum, or FAM, are working to reunite more of them with their families of origin.

The National Endowment for the Arts recently announced that FAM is receiving a $65,000 grant to help the OKC museum continue to reunite Indigenous items collected more than a century ago with their people and tribes in Oklahoma.

What Oklahoma organizations are receiving early 2024 NEA grants?

The National Endowment for the Arts, or NEA, recently announced that organizations across the country would receive more than $32 million in its first round of funding for fiscal year 2024.

The federal agency is awarding nine Oklahoma organizations or people grants totaling $205,000:

El Sistema Oklahoma is receiving a $10,000 grant for a community-based concert series.

The Oklahoma Arts Institute is garnering $15,000 to sustain its annual Summer Arts Institute at Quartz Mountain.

Oklahoma City Repertory Theatre is receiving $15,000 to present contemporary theater. OKC Rep is using the grant to continue its annual "Under the Radar: On the Road" showcase.

OKC's Special Care Inc. is getting $15,000 to support multidisciplinary arts programming for youths.

Tulsa author J.C. Hallman is one of 35 recipients nationwide of this year's NEA Creative Writing Fellowships in fiction and creative nonfiction. The $25,000 fellowships allow recipients to set aside time for writing, research and travel so that they can create new works.

Tulsa's Philbrook Museum of Art is garnering $30,000 to present the exhibit "Making American Artists: Stories from the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, 1776-1976."

Tulsa Glassblowing School is receiving $20,000 for a visiting artist residency program.

The Tahlequah-based Cherokee Nation is receiving $10,000 for an arts therapy program for youth in foster care.

The First Americans Museum's $65,000 grant to continue research into items on 10-year loan from the Smithsonian is believed to be one of the biggest NEA grants ever given to an Oklahoma institution.

"It's the largest for any of the projects I've ever worked on ... and I'm so grateful to be here, to be leading this and to be a part of it," said Director of Curatorial Affairs heather ahtone, who is Choctaw and Chickasaw. "FAM is open now, and we're going to do everything we can to make every day matter. It's a privilege to do this work."

How are the efforts of First Americans Museum helping to right past wrongs for Native families?

After interning there, Pepper Henry returned to work for the Smithsonian's National Museum of the American Indian from 1998 to 2007. During that time, he was part of opening the National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, D.C., and he drafted an agreement to loan items from the Smithsonian that were collected in Oklahoma to what would become the First Americans Museum.

"They were just in the basement; they weren't going to be seen by anybody. I tell people, it's like 'Raiders of the Lost Ark' when the Ark of the Covenant goes into the crate at the end of the movie and there's just all the other crates. That's the Smithsonian," said Pepper Henry, who is also vice chair of the Kaw Nation Tribal Council.

"All the way back then, not knowing that I'd be the director 17 years later of the First Americans Museum, I was adamant that the Smithsonian loan the collections that were taken from the tribes in Oklahoma between 1909 and 1914 and bring them back. And the amazing thing is (how) we've been able to reunite the families who had no idea these things existed."

One of FAM's inaugural exhibits, "WINIKO: Life of an Object" features three or four objects representing each of the state's 39 tribes, and every object was carefully selected from the Smithsonian's collection.

The National Museum of the American Indian collection is built on the vast personal collection of George Gustav Heye, a New York mining engineer who began collecting Native American artifacts in 1896 while working in Arizona. Anthropologist Mark R. Harrington worked for Heye collecting Indigenous objects, including in Oklahoma, where hundreds of tribal members forced to relocate and adapt to a monetary culture were desperate enough to sell their prized possessions for a pittance.

As he traveled the state collecting the items, Harrington would note what the object was, how much he paid for it, which tribe and family it came from and where he acquired it.

"In our initial gallery research, (curatorial specialist) Welana Queton, who's Osage, Muscogee and Cherokee ... and I were looking at those archival notes in relationship to the objects that we had selected. And Welana and I are looking at each other going, 'Is this a descendant of this person that has the same last name? Because if it is, then it's within the realm of possibility that we are able to connect them — and if we can, shouldn't we?" ahtone recalled.

Products of their time, Harrington and Heye believed that Native Americans were a vanishing people and that collecting their material culture items would save the precious objects for the benefit of future generations. Instead, they effectively robbed many Indigenous families and communities of pieces of their heritage.

"We were only about six months into that research when COVID hit. We were able to reunite three of the objects with their either descendant family specifically or with the community more broadly," ahtone said. "But at that point, we were literally making a conscientious decision to terminate that research out of an abundance of care for our community."

How are First Americans Museum staffers readying to reunite more Native families with items from the ancestors?

FAM staffers then turned their attention to getting the long-awaited museum open in fall 2021.

After, ahtone said one of her colleagues at the Smithsonian, Cynthia Chavez Lamar, who was named director of the National Museum of the American Indian in 2022, encouraged her to circle back to the researching the origins of the "WINIKO" objects.

"I think all of us recognize the critical importance of really pursuing this ... but at that point, I neither had the staff, nor the resources," ahtone said.

For the past year, the curator said she and her team have resumed the research, with support from the Ford Foundation, the Terra Foundation and the Henry Luce Foundation.

"The NEA grant is supporting the complete package of this research, which will be concluded by the end of this year. It allowed me to hire people into our curatorial team to specifically pursue this research with our tribal communities," ahtone said. "We are in conversation with the tribes now, and they are keen to have this research done. They've been incredibly generous, active partners in the process."

Although it took almost 40 years for FAM to evolve from dream to reality, ahtone said the OKC institution opened with a focus on giving Native peoples the chance to tell their stories, even as other museums across the country are reevaluating their representation of Indigenous cultures and reckoning with the racism that has underpinned their relationships with Native communities.

"There has been a reckoning for cultural awareness and a sensitivity that there are different cultural paradigms in understanding how the world operates. ... From an Indigenous perspective, we see these objects as relatives," she said. "Our community has always believed this way ... but that reckoning has opened the door for us to ask questions and have a conversation about that without simply being dismissed."

After witnessing previous reunions between Native families and their ancestors' personal items — including a traditional Osage coat owned by Henry Red Eagle and a breechcloth, or rérokina, that belonged to Iowa tribal member Benjamin Hallowell — ahtone said she is eager to schedule more of the meaningful meetings for later this year.

"They're so emotional for the families. ... It's already evident that not every item will have a singular reunion; some of them will have one or two. Given all of that, we're thinking through how to make that work, not only for us and the objects and the safety of the objects, but also for the families and the communities," ahtone said. "So, it's going to be a really busy rest of this year ... but it's going to be amazing."

After Smithsonian leadership attended a meeting last summer at FAM, Pepper Henry said they've been inspired to look at their collections in a new light.

"With the research that we've done connecting those families with those objects, we've expanded our knowledge exponentially ... and heard some really, really incredible stories," he said.

"'Winiko' is a Caddo word that means the life in everything, even inanimate objects … and we begin to understand that these aren't just inanimate objects that are on display."

'Winiko: Life of An Object'

Where: First Americans Museum, 659 First Americans Blvd.

Museum hours: 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. Monday, Wednesday, Thursday and Friday and 11 a.m. to 5 p.m. Saturday-Sunday.

Tickets and information: https://famok.org.

This article originally appeared on Oklahoman: OKC museum to resume reuniting Native American items with families