The first paparazzo: How Sergio Strizzi captured stars’ tender moments in the golden age of cinema

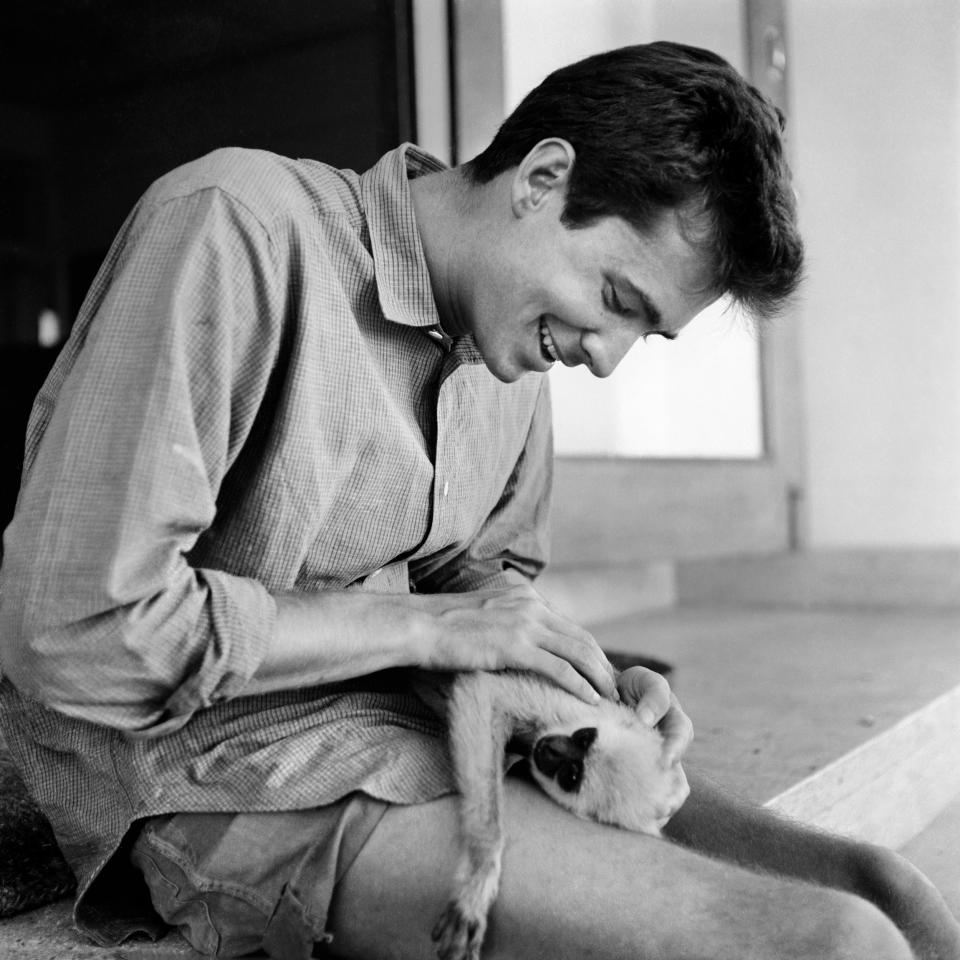

When asked for the secret to his tender, unguarded photographs of cinema’s biggest stars, Sergio Strizzi would simply say: “I wait. Some people come, take a picture and go on to do something else. But I wait: for the light, for a gesture, for something to start a dialogue.”

Strizzi worked as a stills photographer on European film sets from 1952 until shortly before his death, aged 73, in 2004. Time and again, he would capture moments of quiet reflection, passionate debate and spontaneous laughter in the careers of such glittering figures as Audrey Hepburn, Alain Delon, Anouk Aimée and Michael Caine. As the Estorick Collection in north London prepares to open the first British exhibition of Strizzi’s photography, his daughter Vanessa, speaking from her home in Rome, recalls the special gift her “charming, funny, professional” father had for “gaining the trust of his subjects, especially women. I think you can really see from the photographs that women trusted him,” she says.

Strizzi was a self-taught photographer who learned his craft as a boy mucking about in a darkroom belonging to a friend’s father. His own father was an anarchist who had fled fascist Italy before the war, leaving his wife and four children (of which Sergio was the third) to fend for themselves. As a child, Strizzi began earning an adult wage running a paint shop for a man who’d lost his leg in an air raid, before landing a job as general dogsbody at a branch of the national photography agency, Publifoto, at the age of 14.

“One day my father saw an advertisement for a local model aircraft display,” says Vanessa. “It was on a Sunday. He had the keys to the agency because he was meant to go in early on Monday to clean. So he let himself in and took a camera and two rolls of film: one to practise loading the camera and one to shoot pictures of the flying machines.”

The following week, one of his photographs was used on the front page of the national newspaper Il Popolo. The agency’s astonished owner handed over the keys to his car, telling Strizzi to go and photograph whatever he liked. By 1948, this gifted teenage snapper had landed a commission to cover the national elections.

Vanessa identifies that as the moment her father became “a paparazzo before the word existed”. (The term originated as the name of a fictional news photographer in Federico Fellini’s 1960 film La Dolce Vita). She explains that working as a photojournalist taught her father “when to wait and when to seize the moment. He couldn’t snap away the way people can today; back then, photographers would be sent out with only one or two rolls of film of 12 shots. You had only 12 chances to get the right image or you would lose your job. Every shot had to count.”

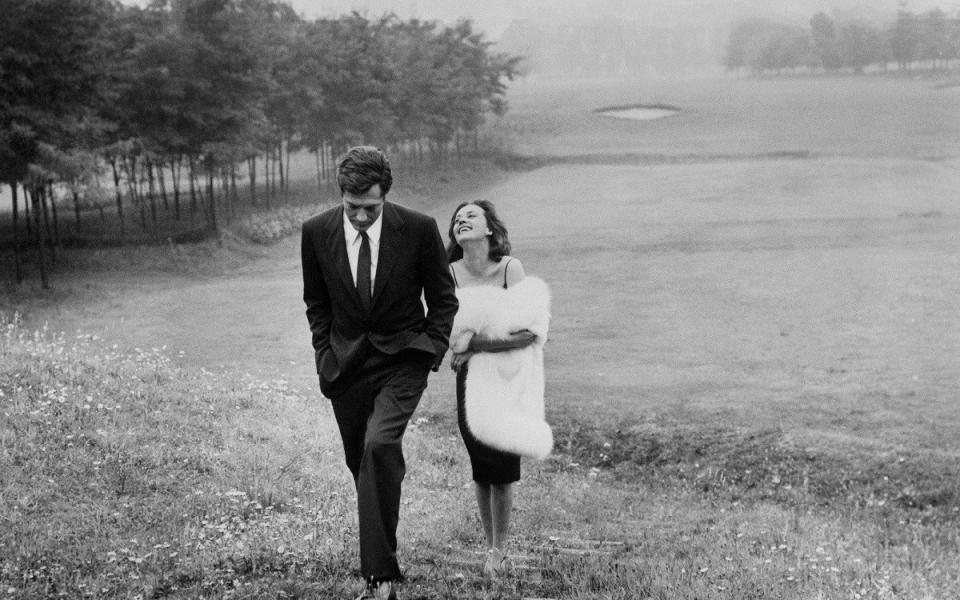

In 1952, Strizzi was invited to take stills on the set of a sports film called The Eleven Musketeers; he had found his niche. He would go on to document the making of Italian classics such as Vittorio De Sica’s The Gold of Naples (1954), Mario Soldati’s The River Girl (1955) and Mario Monicelli’s The Great War (1959). Next he chronicled Michelangelo Antonioni’s acclaimed series of alienation: La notte (1961), L’eclisse (1962) and Red Desert (1964), all starring Monica Vitti, the director’s lover at the time.

Strizzi shot Vitti in a spaghetti-strapped dress, leaning against the glass wall of a high-rise office block like a thwarted 1960s Rapunzel. And again, lying on her back in the same room, laughing as she plays cat’s cradle. These images now look ahead of their time, igniting a spirit that fashion photography would take a decade to rekindle. Antonioni, meanwhile, is captured sitting on the grass, wearing only one loafer and glowering at the photographer with whom he would have several blazing rows.

Strizzi’s daughter says her father used to walk away from sets on which controlling directors or cinematographers prevented him from doing his job properly. “He didn’t get on well with Ken Russell,” she says, “and he walked off the set of The Godfather Part III without pay because the director of photography, Gordon Willis, wouldn’t give him time to take pictures.”

But when he was treated with respect, Strizzi would become invisible to the actors, who would forget his lens was trained on them. And when he put his camera down he became a team player, Vanessa says. “He was a great chef and would cook pasta for everyone on set – he made wonderful carbonara and amatriciana sauces.”

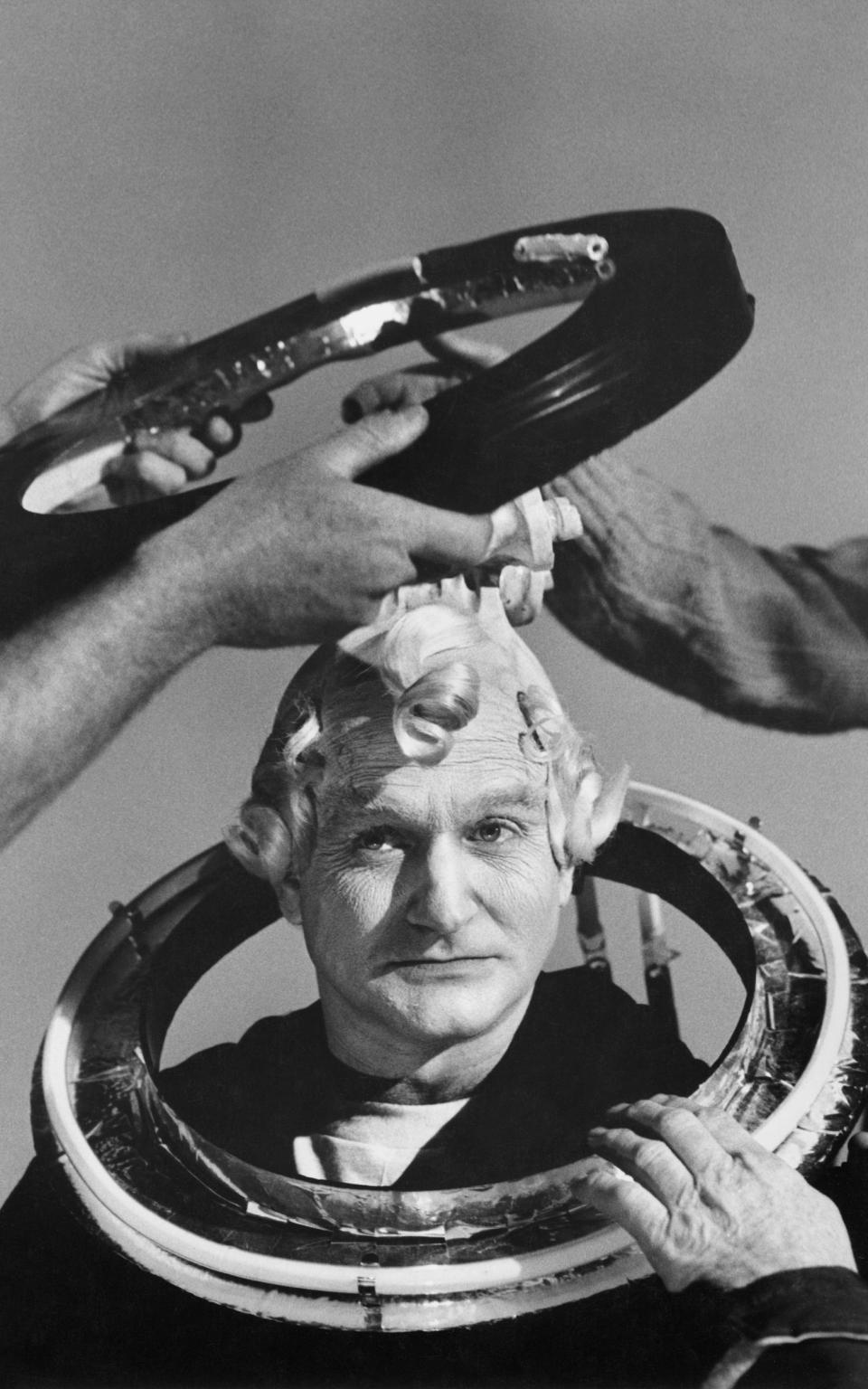

Although he spoke barely a word of English, Strizzi was invited out to South Africa to shoot on the set of Zulu (1964) where he forged a lifelong friendship with Michael Caine. He also worked on several James Bond films. Vanessa recalls the awkward moment when he showed his first pictures taken on the set of You Only Live Twice (1967), to producer Albert “Cubby” Broccoli and star Sean Connery. “They said the photos were ‘terrific!’,” she tells me. “Well that means ‘great’ in English but in Italian it means ‘horrible’. He was so upset! My mother had to calm him down and explain what they meant!”

Vanessa’s favourite photograph from her father’s 007 days shows director Lewis Gilbert and screenwriter Roald Dahl sitting on a desk. “Both of them are focused on their work, looking in different directions, in different moods,” she says. “It gives the personality of both men.”

In the year Audrey Hepburn turned 50, she chose Strizzi to photograph her in Paris for a feature published in Life magazine, after the pair had bonded while working on the set of Bloodline (1979). Over the following decade he would work on John Huston’s Escape to Victory and Terry Gilliam’s The Adventures of Baron Munchausen. Increasingly recognised by filmmakers as a great artist in his own right, Strizzi commanded high fees for his work, which, says Vanessa, “meant a lot to him after growing up so poor”.

Although by the end of his career Strizzi was expected to take 70 per cent of his photographs in colour and 30 per cent in black and white, he would have preferred those percentages to be reversed. His daughter says he didn’t get on with the digital cameras of that era “because those early ones had a delay between the click of the button and the picture being taken. He said they missed the moment.”

On the subject of missed moments, she notes that her father became so much in demand on film sets around the world that “he was almost never at home when my sister and I were growing up”. She sighs. “So we don’t have any photographs of our birthday parties, our special family occasions, nothing!”

Sergio Strizzi: The Perfect Moment is at the Estorick Collection, London N1 (estorickcollection.com), from Weds to Sept 8