Foraging Felt Like a Fad From the Past. Turns Out It Was a Reality Check I Didn’t Know I Needed.

Fiddleheads, I’ve learned, are named for the way their green tips coil inward like the spiraling scroll of a violin. A natural immune booster and a source of iron and antioxidants, they’ve been part of the traditional diet in Northern France since the Middle Ages, and eaten by the indigenous Mi’kmaq and Penobscot tribes for centuries. Growing up in Southern Ontario, I’d picked them as a child. Still, if you had told me, at the beginning of March, that by mid-April I’d be holed up in a bungalow at the foot of the Appalachians foraging for fiddleheads from ostrich ferns, I wouldn’t have believed you.

In the beginning of March I was splurging on a bikini wax, a seaweed facial, and a ticket to Los Angeles. At that time, there was only a handful of known COVID-19 cases in my state. I planned the rendezvous in Joshua Tree and the brunch at Lasa, an afternoon at the Broad. But a week later, as my anxiety began to mount, I upended my packed suitcase in the middle of the room, cancelling my ticket less than two hours before departure. I couldn’t fathom leaving the house, much less getting on a crowded airplane headed for a destination three thousand miles away.

The decision felt existential somehow; would I spend the unforeseeable future quarantined in the forest, or by the sea? I’d been diagnosed recently with pneumonia and anemia, and I’d planned to stay the rest of the month on the West Coast, recovering while working remotely. But that morning the thought of venturing far from home didn’t seem so inviting. Over the next few days, what I thought had been peak hypochondria soon morphed into something else: obsessive-compulsive sanitation of any object in sight, petrification at the thought of even leaving the house. The supermarket was close, and I’d been wearing masks because of my underlying condition, but was there a way to reduce public life completely?

The fiddleheads, spring’s most ephemeral vegetable, provided an answer. Hadn’t even Shakespeare believed in their antidotal powers? In Henry IV, the thief Gadshill credits “fern seed” for rendering him invisible. Fitting for a newly agoraphobic writer with a respiratory infection, sequestered with family in Western Maryland, steps from the Appalachian trail. If foraging felt like a fad in the past, now it seemed like an act of preservation.

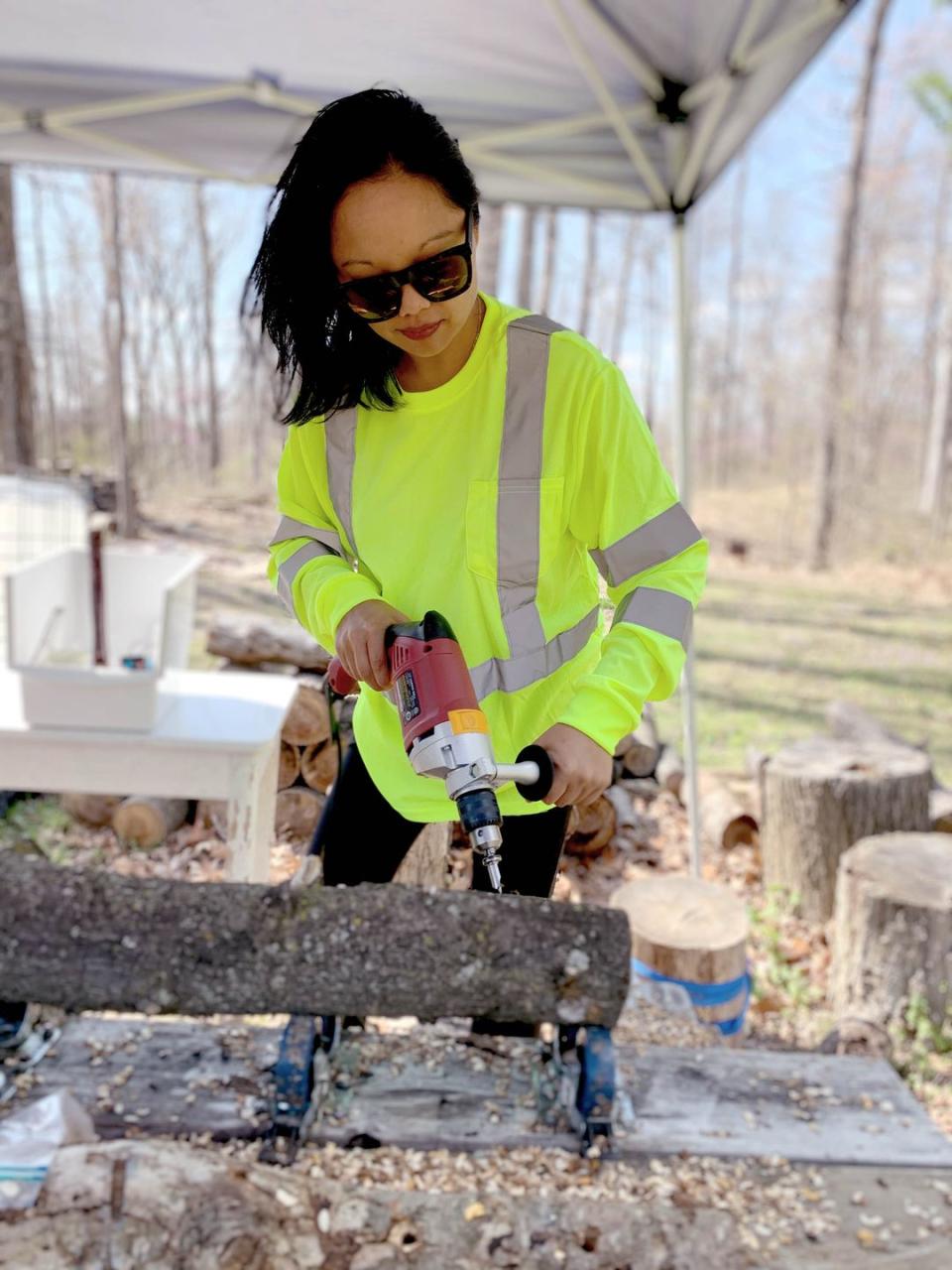

I found a patch of ostrich ferns on the property, the mint-green tendrils still curled like a nautilus shell, sheathed by papery, brown scales that flaked off with the slightest touch. When boiled (ten minutes to rid them of any potential toxins), the fiddleheads smelled faintly of sweetgrass and walnuts. The next day, guided by my parents—a mycologist and an environmental educator—I found over a dozen morels: enough for a midday omelet. Since we were looking for mushrooms, why not grow some ourselves? Donning safety goggles and a dust mask, we spent one afternoon drilling a diamond pattern of holes into oak logs and inoculating them with shiitake spore; in six months to a year they will fruit.

In addition to the fiddleheads, we discovered wide swathes of garlic mustard, growing unimpeded a few meters away. It wasn’t hard to identify; the leaves were kidney shaped with scalloped edges, and there were patches sprouting up everywhere I looked. The garlic mustard was usurping the back end of the property, covering winter’s natural detritus with a billowing verdigris. Some of them were already flowering, a cluster of delicate, white blossoms crowning each plant. An invasive species, but edible, the average garlic mustard plant produces up to 600 seeds arranged in slender capsules. I’ve read that a square yard of infested woodland can produce over 10,000 seeds, which are easily spread by human or animal feet.

But harvesting and tasting this noxious plant made it hard to hate—I crushed the leaves and root (the roots have a riotous flavor, like horseradish) with ground walnut, raw garlic, olive oil, and himalayan salt, for a pesto that made the inside of my mouth pucker, like from an unexpected kiss.

Not that I needed a reality check, but the temporality of the food I foraged—in-season for only a few weeks a year—was a reminder of my own mortality. Separated from friends, deprived for the most part from human touch, wasn’t food one of the few remaining sensual pleasures? Foraging was an act of self-care and resilience, adapting to a reality that was ever-shifting. I wasn’t able to forget that just a few weeks ago I’d embraced someone in the middle of Penn Station. I’d lost loved ones, colleagues, people I thought I’d see again. I missed so many things: movie theaters, concert halls, Joshua Tree in the spring. But those were joys I promised myself I’d still have, that would still be there when I emerged.

Eating at the kitchen table, we watched a rafter of wild turkeys sauntering across the lawn. Foraging had brought into focus a return to nature, moving beyond farm-to-table to a profound sense of terroir, made more poignant by the fact that the seasons would pass. What would come next? Rhubarb, ramps? For now, there were the fiddleheads. The furled tips waiting to unravel, heads towards the sun. They signaled a greening, a sign of warmer weather, of better days ahead.

Treat yourself to 85+ years of history-making journalism

SUBSCRIBE TO ESQUIRE MAGAZINE

You Might Also Like