'General Hospital' star Maurice Benard opens up about his bipolar disorder, suffering from anxiety attacks amid pandemic

Mental health has been fragile for everyone amid the coronavirus pandemic, but for Maurice Benard, it’s been an especially slippery slope.

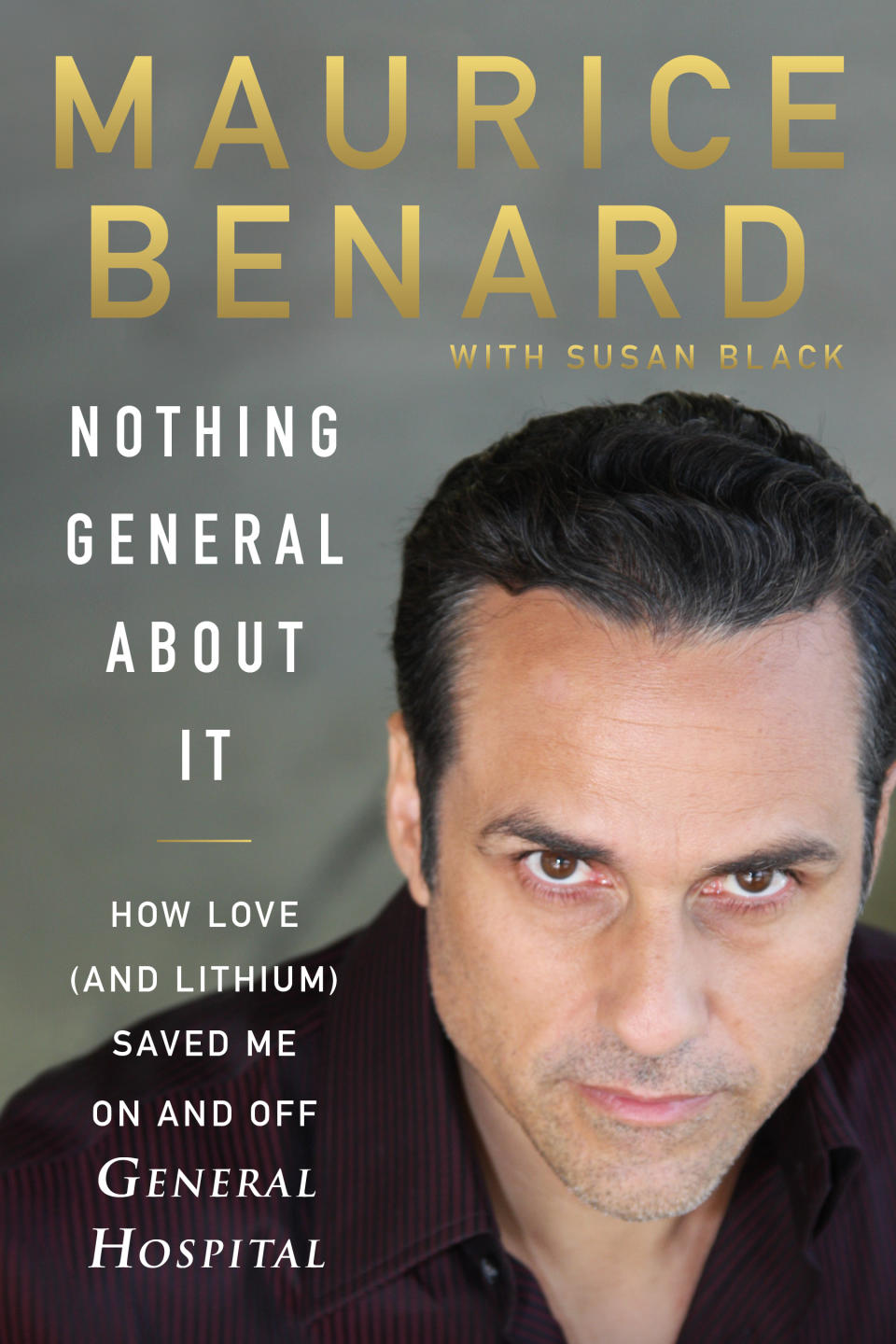

The beloved General Hospital star calls himself the “poster child for mental illness,” having first gone public with his bipolar disorder diagnosis in 2000, and now he’s written about that journey in his new memoir, Nothing General About It: How Love (and Lithium) Saved Me On and Off General Hospital. As that book, a literary wild ride, was released on April 7, life in the U.S. screeched to a halt amid the coronavirus pandemic — and Benard, 57, fell into one of his darkest and most debilitating anxiety episodes ever, which he describes as “two weeks of torture” during the start of quarantine.

“I had two panic attacks that got me,” the actor, who plays formidable mobster Sonny Corinthos on the long-running soap opera, tells Yahoo Entertainment. ”I was able to deal with it — accept it, move through it — but it’s two weeks of torture.”

And make no mistake — the two-time Emmy winner has lived through a lot of mental health struggles. His troubles started as a boy when he had intense nightmares and it escalated to anxiety, manic outbursts, hallucinations, hearing voices and suicidal tendencies. A nervous breakdown at 22 led to him being institutionalized against his will — an experience he compared to the film One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest — and ended when he escaped, running off from the hospital in oversized sneakers that he swapped another patient for. (And you thought soap plots were dramatic.)

Soon after, Benard felt relieved to be diagnosed with bipolar disorder — finally, it had a name — and his extreme highs and lows were balanced by the drug lithium. When he took it, the young, macho male model and aspiring actor thought he had been cured, and stopped taking the medicine. In 1993, two weeks after landing his role on ABC’s General Hospital, he was spiraling, thinking Michael Jackson was speaking to him in his songs, and he had a violent manic episode — in which he threatened his new wife, Paula, and their young nieces — leading to another breakdown and a deep depression as he recovered.

He’s been back on lithium after that and for “27 years I haven’t had a manic episode,” he says. “I can’t mess with it.”

While the manic episodes stopped, the medication is not a cure-all for the star, who continues to suffer from depression and crippling anxiety. The conditions have led to ruined auditions. For more than a decade, he was unable to fly. There are times when he finds himself paralyzed — physically unable to get in his car and drive. He’ll be unable to walk — frozen in place and scared.

“Depression is a heavier feeling,” he explains. “You don’t get out of bed. You just feel negative 24/7. Anxiety, what I’ve felt is a shift, things happen to your body. I am shaking like a leaf — like it’s 30 degrees below 0. It’s scary. And I don’t sleep. So that combination, and negative thoughts, will take you to places you don’t want to go because it’s like: Why am I shaking like I’m going to die? And why can’t i sleep at all? That’s where I was two weeks ago.”

Benard says his routine being upended by the safer-at-home order in California triggered his anxiety. While he relies on a lot of tools to keep his mental health steady — medicine, therapy, exercise, meditation, a healthy diet, visualization and therapy animals — the pandemic upset that routine.

“I hadn’t been meditating in a long time, so I started meditating again,” he says, citing the Calm app. “I go to my goats and alpacas outside” on the rural estate he shares with Paula, whom he has been married to fo nearly 30 years, “and I do breathing exercises.” He also resumed his workouts. “What happened was I didn’t exercise for a bit because I was in such a thing. So then I started working out again, I got my fight back.” He runs, lifts weights and boxes — all things he’s able to do at home.

For those struggling at home, he advises, “Keep doing the routine you were doing before you were stuck at home. It’s one thing to be stuck home, it’s another to be stuck in bed. When you’re stuck in bed, that’s when depression comes. So I know for myself, even now that I feel much better, when I wake up in the morning and still feel a little thing, I still get out of bed, man.”

But there’s one good thing that’s come out of the pandemic, says Benard, who has received numerous awards for his work raising awareness about mental health.

“What this coronavirus has done, it’s been a light shining on mental health,” he says. “Now people are seeing what can really happen under pressure. It’s always been there, but this is something nobody’s ever seen. Everything’s out of control. And maybe, in a sense, my book wouldn’t have done as well if it wasn’t for coronavirus,” he says of the New York Times Best Seller. “I think people are starting to [pay attention]. It’s time.”

When Benard was starting out a young actor — his first daytime role was Nico Kelly on All My Children in the late ‘80s — he was advised by an acting coach not to reveal his bipolar diagnosis or he wouldn’t be hired.

“Especially at that time, people weren’t ready for it,” he says.

It wasn’t until 2000 — seven years after his breakdown while working on General Hospital — that he first bravely mentioned his mental illness publicly. That opened the floodgates.

“A kid wrote to me, because I had written something in this magazine, and said by reading what I wrote, it helped him deal with his brother’s suicide,” he recalls. “After that, I said: OK. Well, I’m gonna talk about this. And I’ve been talking about it — I’ve been yelling it, shouting it — for 20 years.”

You’d think playing a soap role would be a fun, light way to escape real life for Benard, but if you’ve caught a minute of him as Sonny — in his nearly three decades on the show — you know his counterpart is intense. And the mobster is also bipolar, something Benard suggested to writers in 2006 as he began his mental health advocacy.

“Sometimes it’s been great, sometimes it hasn’t,” Benard says when asked if he regrets making the suggestion. “But I signed up for all this: Mental health. Mental illness. Bipolar guy.... And I don’t have a problem because I know how many people I’ve helped — and how many I’m going to help. But there are times, like the last two weeks, that I need to know how to help myself.”

Unlike many celebrity memoirs, Benard’s doesn’t make the reader feel like he’s trying to make you like him the whole time you’re reading it. He paints his flaws — vividly — detailing that incident in which he threatened Paula’s life as well as cheating on her before they were married and falling for a stripper after they had tied the knot. (It was unrequited — and all these things happened when his mental health was unstable.)

“It wasn’t so hard” revisiting these painful moments for the memoir, he says, “because I’m an open book. I pretty much talk about everything.” As for Paula, who’s also his manager, “it’s so behind her now. She just appreciates that the book is good and that I’m getting some acclaim... She worked hard on the book also.”

Benard met his wife when she was 16 and she’s been on this wild journey with him throughout. (“The second book would be from her perspective,” he says, already planning. “People want to see it from her side.”) They raised four kids together, which hasn’t been easy for someone like Benard who struggles. The book detailed cancelled vacations because dad couldn’t get on an airplane — and a family trip to Las Vegas where he remained in bed most of the time. He also detailed an incident in which he screamed at his son, Joshua, now 14. (They’re also parents to Heather, 27, Cailey, 25, and Cassidy, 21.)

“It’s very difficult when your kids don’t understand why dad looks different,” he says. “Why he looks like he’s scared or why he looks like he can’t walk... [My children] have seen now three times I think with anxiety. It’s really hard on the person, on me, because I don’t like that my children have to see me in such a weak state of mind.”

While the book is about his mental health struggle, General Hospital fans won’t be disappointed. He talks about his onscreen leading ladies (he texts Vanessa Marcil, who played Brenda, all the time), storylines he loved (including Stone’s groundbreaking AIDS diagnosis), trouble with co-stars (including Tamara Braun and Chad Duell) and blowups on the set (“I’m pretty intense”).

As for the return-to-work plan, “Nobody really knows, but it looks like June 1” if things go according to plan, he says. The show had enough banked material through mid-May. “They’re stretching it out right now,” by adding flashbacks to new episodes and only airing four new shows a week along with one classic show. After that, they’ll have to air all classics.

While Benard has taken breaks from the show — including to make films, like 2015’s Joy starring Jennifer Lawrence and 2018’s Nightmare Cinema with Mickey Rourke — he’s in it for the long haul, he says.

“After this virus, the coronavirus, I’m cool. I’ll stay there until it ends,” he says of the show that debuted in 1963. Time away certainly makes him “appreciate it,” he says. “And I’ve done other stuff the last two to three years — I’ve done movies of the week, movies, this that — and the grass ain’t greener.” (His book details playing John Gotti in 2019’s Victoria Gotti: My Father's Daughter and dealing with a producer who “clearly didn’t want me in the role and made it miserable for me.”)

Benard’s book is out now and he hosts weekly chats about living with mental health — Sunday Sessions/State of Mind talks — on Instagram. “I’m not a doctor, but I’m the poster child for mental illness now I think,” he says, “I”m proud of it and I’ll keep doing it because it’s bigger than me.”

Read more from Yahoo Entertainment: