Gilda Radner Found the ‘Funny Side’ of Things in Her ‘Darkest Moments’ Before Cancer-Related Death

Former Saturday Night Live writer Alan Zweibel recalls being so nervous at his first cast meeting that he hid behind a plant in producer Lorne Michaels’ office. Gilda Radner found him, asked if he could help her write dialogue for a parakeet sketch and offered to sit with him. “She said, ‘It’s my first TV show, and I’m a little nervous, too,’” he recalls to Closer.

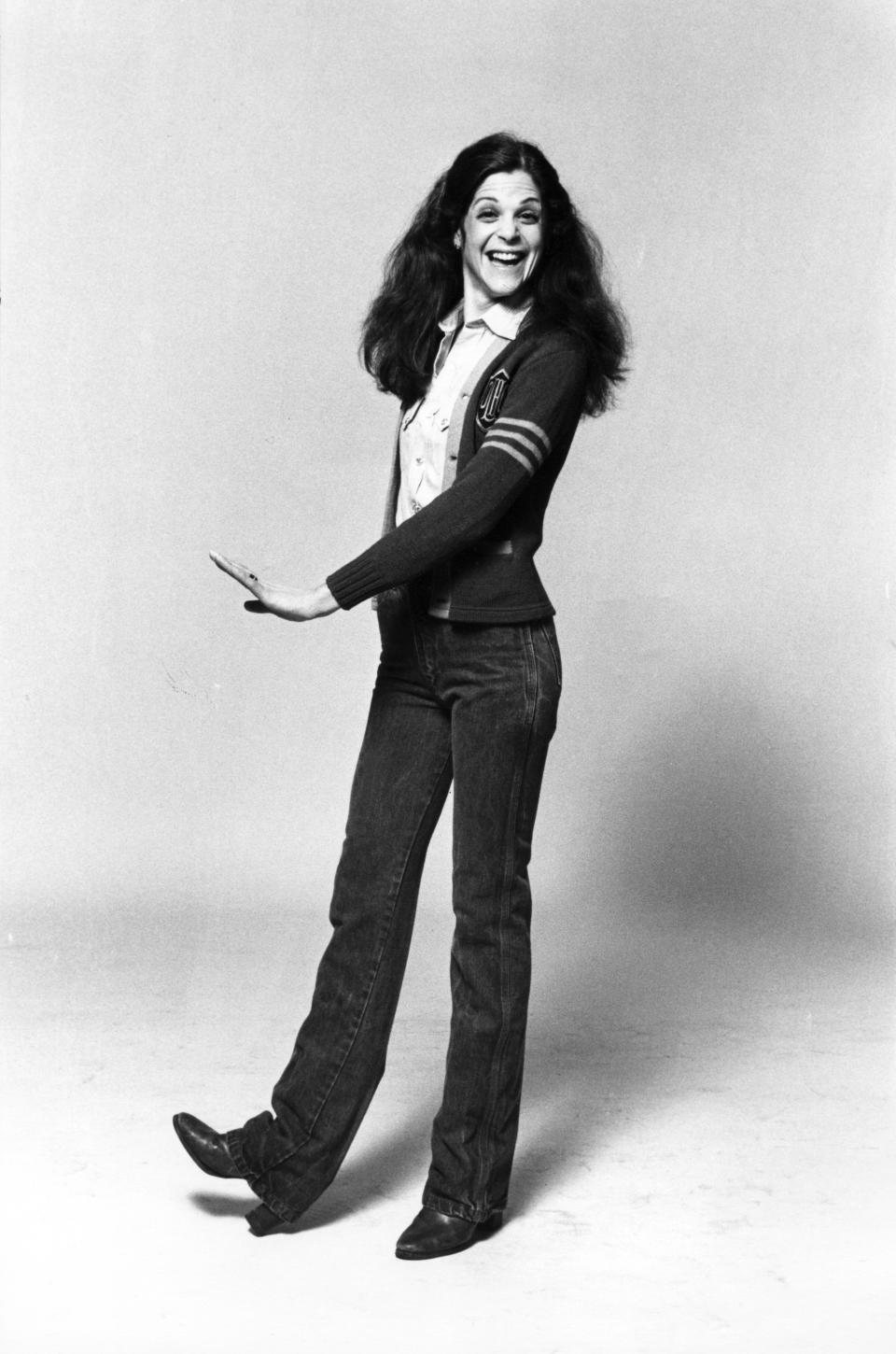

On SNL, Gilda helped blaze a trail and prove, without question, that women could be as funny as men. Her fearless pursuit of a laugh allowed her to go toe-to-toe with the best comedians of her generation, but it’s her giant heart that has kept her memory alive for the past 34 years.

“What was special about Gilda is that you could see her true sweetness. She was able to showcase that in characters like Judy Miller and Emily Litella,” SNL alum Laraine Newman tells Closer, adding that Gilda also ran with the boys playing “gross, subversive and hard-edged characters like Roseanne Roseannadanna and CandySlice.”

It seemed exceedingly cruel that such a talented, universally loved person should die young — but before she passed at 42, Gilda initiated a bigger conversation about the needs of cancer patients. “To me, her connection to the world of cancer was unique,” Lisa D’Apolito, director of the 2018 documentary Love, Gilda, tells Closer. “Her book, It’s Always Something, and organization, Gilda’s Club, have made such an impact on people’s lives.”

Gilda came from a well-off family in Detroit. “When she was born, she became the apple of my father’s eye,” her older brother, Michael Radner, tells Closer. “He loved show business, and she used to sing and perform for him. She loved doing it because it made him so happy.”

When her father became ill with an inoperable brain tumor, Gilda’s family tried to shield her from the worst of it. His death when Gilda was 13 upended her world. “It was devastating to her,” says Michael.

That early loss would always color Gilda’s relationships with men. “She was very open about how she was always looking to replace her dad,” says Zweibel, who wrote Bunny Bunny: Gilda Radner: A Sort of Love Story about their close friendship.

A failed romance landed Gilda in Toronto, where she joined the Second City comedy troupe in 1973 and became a featured performer on the National Lampoon Radio Hour. “If you love to do it, do whatever you can to be around or near what you love,” she said of performing. Producer Lorne Michaels recognized her talent, and Gilda became the first person he cast for SNL in 1975.

In the early years, she, Laraine and Jane Curtin shared a dressing room. “In retrospect, it’s remarkable that there was no ‘mean girl’ behavior amongst us. It formed a great sisterhood,” said Laraine.

Gilda also spent hours with Zweibel developing characters, like hard-of-hearing Emily Litella, who was based on her childhood housekeeper. “What a ride it was for all of us!” Zweibel says. “It was playtime. It was fun. And Gilda got all the adoration she ever wanted because she was the darling.”

Success, of course, had its drawbacks. After the initial thrill of being recognized on the street, Gilda found she missed her anonymity. The eating issues she’d carried since childhood grew worse. People befriended her to help their careers. The weekly SNL schedule was also grueling. “Quite often I heard her say, ‘I just want a life,’” says Laraine.

By 1982, Gilda had left SNL, gotten help for her eating disorder and started doing movies. She fell in love with Gene Wilder on the set of Hanky Panky. Unlike a lot of men she had dated, Gene was older, established and had his own money. “In Gene, she found the man she had been looking for her whole life,” says Michael, who adds that Gene was quieter than the manic characters he played in films. “If you met him, you’d think he was a college professor teaching philosophy.”

The couple would costar in two other films, The Woman in Red, released in 1984, the year they wed, and Haunted Honeymoon in 1986. Gilda also threw herself into baking and decorating their home. “Gilda was a Jewish housewife who was stuck in this incredibly talented body,” says Zweibel.

But her inability to conceive sent her to doctors. After many wrong turns, Gilda was diagnosed with stage 4 ovarian cancer in 1986. During treatment and despite the support of everyone around her, Gilda felt alone and eventually turned to the Wellness Community, a place where patients could come together and talk.

“I think finding community was what helped Gilda the most,” says D’Apolito. “That was her impetus of writing her book.” Humor helped, too. “Even in the darkest moments, Gilda was always finding the funny side in things. I think that’s how she coped,” D’Apolito says. Today, the Wellness Community has merged with Gilda’s Club, a support group founded in the star’s honor, to become the global Cancer Support Community (CSC).

During a period of remission, Gilda attended a party with her former SNL costars. “We hadn’t seen her in a long time. And she started doing, ‘I’ve got to go,’” said Bill Murray. “So we started carrying her around. … And we said goodbye to the same people 10, 20 times.”

No matter how much time passed, Gilda never forgot her friends — for years she sent Laraine sushi for her birthday. “She called me twice to say goodbye. I missed both of the calls, much to my continued grief,” Laraine says. “She said, ‘I love you.’ It still makes me cry when I think about it.”

Gilda died in 1989, a short time after her book, It’s Always Something, was published. She had wanted a happy ending, but it was not to be. “Like my life, this book has ambiguity,” Gilda wrote. “Like my life, this book is about not knowing, having to change, taking the moment and making the best of it, without knowing what’s going to happen next.”