"I do like a good yarn!" Rick Wakeman and Journey To The Centre Of The Earth

Rick Wakeman vividly remembers the day he was presented with his first gold (“or platinum, or whatever it was”) disc for Journey To The Centre Of The Earth, at a music industry conference Midem. In a proud moment for irony, one of the heads of A&M, who had been “very anti” the album and hadn’t wanted it released, was doing the honours in front of a shedload of journalists. “He stood up,” recalls Rick, “and spoke words to the effect of: ‘Every now and then, an album lands on your desk and the minute you hear it you know you’ve got something very special here. Something you must nurture and go forward with. And that’s exactly how I felt when Journey To The Centre Of The Earth came to me.’”

Our man, waiting at the side of the stage, felt his jaw dropping with disbelief. “But what was really brilliant, as I approached him, under the applause he leaned over into my ear and said, very clearly: ‘Don’t. You. Fucking. Dare!’”

So onstage, Rick, choosing the route of diplomacy, declared his gratitude to A&M and afterwards the pair shook hands. “Many years later, with A&M long since sold off, this guy was asked about the history of the label – The Carpenters, The Police, The Tubes (who, by the way, I took to A&M co-founder Jerry Moss, Fee Waybill being a close friend) – and then they came to the ‘and Rick Wakeman?’ bit. The chap acknowledged that I had the label’s first UK Number One album and other massive sellers. ‘The interesting thing was,’ he said, ‘that I neither liked nor understood one single note of anything he ever recorded or played. I used to sit in my office and think, but why should I fucking question it? He paid for most of this.’ He added that, ‘You don’t always have to like everything you release. Thankfully, there were millions of people who did. So probably I was the one that was wrong.’ I’ve seen him since and we laugh about it and he says, ‘I still don’t get it…’”

Journey To The Centre Of The Earth, and the works of Jules Verne in general, had been a passion of Rick’s since he first read a compendium borrowed from the school library, aged about 12. He knew then he wanted to adapt it, having been enchanted by Prokofiev’s Peter And The Wolf, which his dad had taken him to see four years earlier. “How wonderful to tell stories with music,” he thought.

“And I do like a good yarn; a story with a beginning, a middle and an end,” he tells me. His own Journey… has now become one of those. A happy ending is within view."

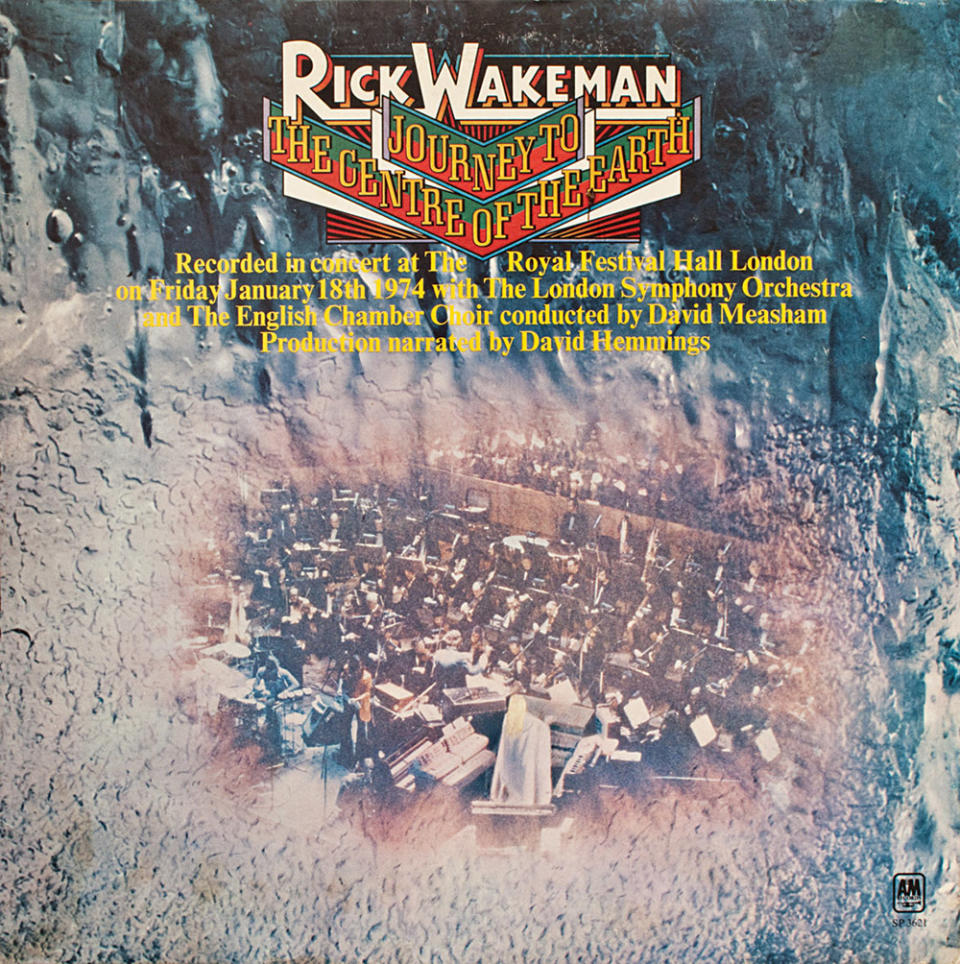

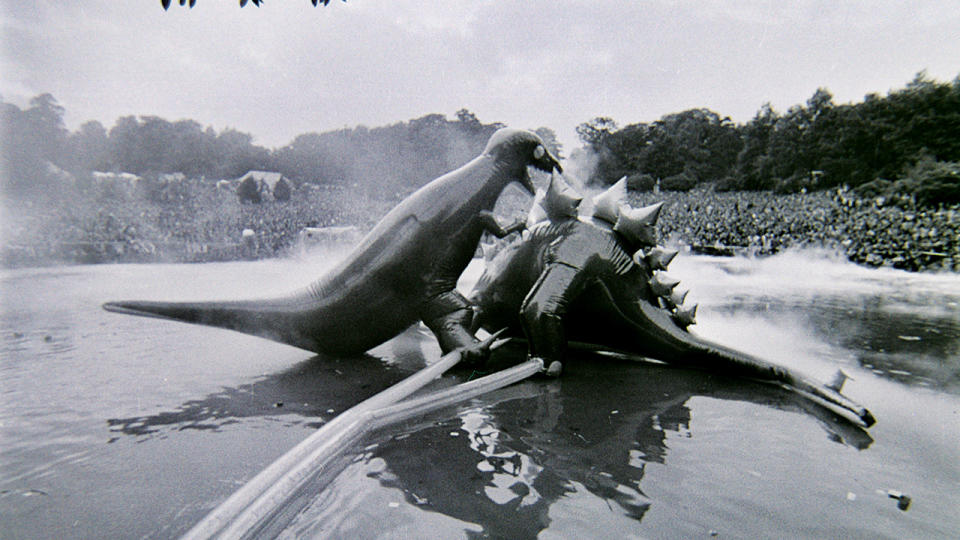

Wakeman recorded the original live at the Royal Festival Hall in January 1974, with the London Symphony Orchestra and the actor David Hemmings narrating. It cost a fortune, was unloved by the label in the UK until Rick took it to Jerry Moss (the M in A&M) in the US, and our caped crusader had to sell everything he had to make it happen. Famously, he remortgaged his house, flogged some cars, and received a writ for failing to pay the milk bill for two months. He defied common sense by getting his friends from the local pub band to play when names such as Clapton and Blackmore were being suggested. The day after his lavish tour ended, with a show at Crystal Palace Bowl, he had a heart attack and went into hospital for nine weeks (where he wrote the King Arthur… album).

By May of ’74, Journey… was number one in the UK and number three in the US: nothing succeeds like excess. In 2012 the long-lost conductor’s score for the full story, with material pruned to make it fit a single album, mysteriously turned up, and Rick was able to put together a fully realised Abbey Road recording.

Long labelled the epitome of outlandish, pompous pretension, Journey… now sounds like someone’s thrown open the windows in the stuffy, cramped rooms of predictable, prescriptive, musical possibility.

“One thing I’d learnt from David Bowie, while working on Space Oddity, was to fight for what you believe in. He fought tooth and nail for that single to be stereo, which might not sound like much now, but there weren’t many stereo singles then. He said to me: ‘If you battle for what you believe in, and get people around you who believe in you, then you really can make things happen.’ That was key. I was quite happy being a band member, both with Yes and Strawbs, and others. I liked being part of a team, but I’d always had clear ideas of other things I wanted to do. I wouldn’t say it was that I’d lacked the courage to do it but I’d thought it looks very difficult. David said: ‘No, it’s not so difficult.’ And the moment I started pulling in a group of like-minded people, we were on a roll. Journey… was my major breakthrough. Of course in the end it was difficult, with A&M not wanting it, but I persevered by going to America… without Jerry Moss there would be no Journey To The Centre Of The Earth.”

With a Warners box set imminent, Rick’s belief in the va-va-voom of Verne is vindicated all over again. The renowned joker takes his day job seriously. “You’ll have the original live version, plus a remastered version, plus the recent studio version, which for me is the definitive one, as it was meant to be. It’s all there, and it means a lot to me. Without being morbid, I did one of the eulogies at Jon Lord’s funeral, standing very close to his coffin. And I couldn’t help thinking: I wonder what you’ve taken with you, Jon – what other great things would you have given us? So I’m going to continue to cram in as much as much as I bloody well can.”

Did it frustrate him that Journey… – perceived by many as the high water mark of prog preciousness – wasn’t taken seriously for years, after punk’s burning-of-the-books barrage?

“In a way, as I do indeed take the music seriously. A lot of those problems came about even before punk, because in the 70s there was a kind of them-and-us issue between the classical musicians and the rock musicians. I got away with it a bit because I’d been to the Royal College Of Music and done all my bits, so both sides somehow thought: oh, he’s okay, he’s sort of one of us. But back then the classical players couldn’t actually play the stuff. I could write music and give it to classical players and to blues-rock musicians, and their feel for the music was completely different to each other’s. In the 60s and 70s, the classical players were going, ‘Ooh, that dreadful rock stuff!’

“But, yes, for years it was, by some parties, mocked. It was an era of: ‘I don’t understand it, it must be shit.’ Yet if you look back at the early 70s, prog or prog-related bands probably sold more albums than all other types of music put together, in numbers the pop stars of today could only dream of. And still the Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame barely acknowledges that prog ever existed.”

Cause championed, Rick is – as regular Prog readers will be aware – a fan of anything comedic. The thing with his anecdotes and tour stories is that they’re not just “like” Spinal Tap: they almost certainly begat Spinal Tap. “Never mind the film,” he says. “At the time, it was real. The 70s tours I did with Journey..., and other albums, were it. The secret that Spinal Tap hones in on is that when you look back at reality, hindsight shows you how funny it is, even though it wasn’t when it was happening. The first time I saw that film, Jon Anderson and I were watching it together in Montserrat, and when the bass player is caught in the pod, we looked at each other… because that’s exactly what happened to our drummer, Alan White, in one of Roger Dean’s stage sets. Alan was trapped in a giant clam. And the crew had to run on with pick-axes, trying to feed oxygen to him, trying to break him out.”

So did Spinal Tap nick the idea from there? “They had to have: there’s no way they didn’t. I’d like to meet Christopher Guest or Harry Shearer. The ‘11’ on the amp wasn’t us though: that was Pete Townshend. The 70s offered them rich source material.”

Wakeman found his rich source material in Jules Verne’s book, which celebrates its 150th anniversary this year. Now his very own time machine brings Journey To The Centre Of The Earth back to the surface. A return to core values? “Great stories,” muses Rick, “are limitless.”

This article originally appeared in issue 45 of Prog Magazine.