Graham Bond thought he was the son of Aleister Crowley. He was also one of the most influential musicians of the 1960s

The voice on the other end of the phone line was optimistic; enthusiastic, even. “I feel great. I’m clean. I’m off everything and I’m looking forward to getting back to work again.”

It was Tuesday, May 7, 1974, and Graham Bond was calling the NME office to thank them for recently printing an old photo of his. During a cordial exchange, the paper agreed to interview him in the next few days, after which he hung up. There was nothing to suggest anything amiss.

Twenty-four hours later, Bond was dead, crushed under the wheels of a Tube train at Finsbury Park station. It was two days before the police were able to identify the body, and then only from his fingerprints. He was 36. It was a strange, messy end to a strange, unpredictable life.

In his mid-60s prime, Graham Bond was a true originator and one of the key figures on the British music scene. As the driving force behind the Graham Bond Organization, he dragged trad jazz out of its fusty confines and made it jump with heavy doses of blues and wailing R&B. A raft of talent passed through the band on the way to greater success in Cream, Blind Faith, the Mahavishnu Orchestra, Colosseum and elsewhere.

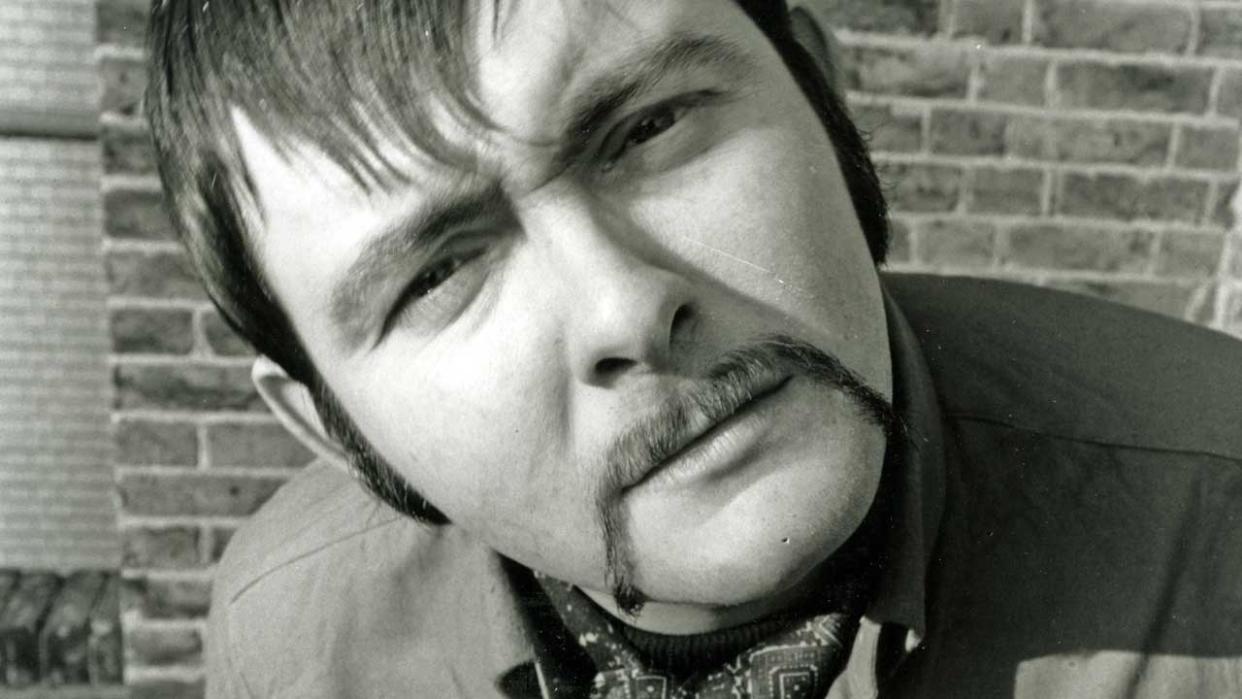

As an organist and alto sax blower, Bond was a primal force. He redefined the role of the keyboard during his time with the GBO, his energy and outsized personality reflected in his ferocious playing and the anguish of his raw singing voice. Bulky and, during his later years, bearded, he was a formidable presence.

“You wouldn’t miss him in a crowd,” says Jack Bruce, who formed Cream with fellow GBO member Ginger Baker. “He was a colourful character and a powerful guy.”

If Bond’s reputation is largely diminished these days, his influence on his fellow musicians is undeniable. The likes of Rick Wakeman, Elton John, Steve Winwood and Deep Purple’s Jon Lord were all indebted to both his musicianship and his showmanship.

“He taught me, hands on, most of what I know about the Hammond organ,” said Lord.

Bond’s pioneering spirit even marked him out as a harbinger of prog – witness his appropriation of classical music, most notably co-opting Bach for 1965’s Wade In The Water.

“Graham was important to a lot of people,” says Bruce. “He was a one-off. Nobody could play alto sax and Hammond at the same time and get that incredible sound. The Organization was a phenomenal band. It was quite primitive, but that was part of the beauty of it.”

But this is where his legacy gets mangled. The great enigma of Bond’s life and career was that, despite packed houses and plaudits from fellow musicians, he never achieved either the fame or the riches his talent deserved. By the time of his death, Bond was reduced to the role of outsider artist, his stock in tatters. The record industry had long given up on a troubled man prone to fits of erratic behaviour, trapped in an auto-destructive cycle of drug abuse and occultism.

“He was his own worst enemy,” says drummer ‘Funky’ Paul Olsen, who played with Bond in his final days. “He was supremely intelligent, but there was just too much going on in his head.”

The turn-of-the-70s Bond was a world away from the one who gatecrashed the music fraternity a decade earlier. Initially a saxophonist, Bond had studied music at the Royal Liberty School in London before landing a job with the Goudie Charles Quintet. By 1961 he’d signed up with the Don Rendell New Quintet, where his exuberant style and unique phrasing brought him to the attention of the jazz press. Bond’s recorded debut came on the Quintet’s album Roarin’, released later that year. In Melody Maker’s year-end jazz poll, his prowess was such that he was voted second in the New Star category.

The following year was a pivotal one. As well as playing with Don Rendell, he also began gigging with the Johnny Burch Octet, a ‘budget big band’ whose members included double-bassist Jack Bruce, drummer Ginger Baker and tenor sax player Dick Heckstall-Smith.

“I first met him at one of the all-nighters at the Flamingo,” Bruce recalls. “Graham used to sit in with us. His appearance reminded me of Cannonball Adderley, and the intensity just astounding.”

By October 1962, Bond had graduated to Alexis Korner’s Blues Incorporated, a hothouse for emerging talent. He doubled up on the sax by pumping out fat Hammond riffs through a Leslie speaker, brokering a new style of American-influenced R&B. Bond, Baker and Bruce, also in the line-up, began playing as a trio during intervals.

It’s not exactly clear just when Bond decided to start his own band, although a trip to Manchester in February 1963 appears to have been a turning point. He’d secured a trio gig and travelled up in a hired black Dormobile camper van with Baker and Bruce. The audience howled their appreciation of their wild, free-ranging approach. Not long after, Bond told Korner he was breaking off on his own, with Ginger and Jack in tow. It was typical of his single-minded bullishness that he never bothered to consult with those two first.

“I just showed up for rehearsal one day and Alexis was looking very glum and angry,” Bruce remembers. “He wouldn’t talk to me at all. Then I found out that I’d resigned from the band! I was very naive in those days, just a kid. I should’ve said something, but just went along with it. It was years before Alexis began talking to me again.”

Three became four when guitarist John McLaughlin joined from Georgie Fame’s band. The Graham Bond Quartet’s first release found them backing emergent rock’n’roller Duffy Power on a cover of The Beatles’ I Saw Her Standing There.

“Graham’s influence on me was enormous,” admits Power. “He was a natural musician and had a philosophy where you must always go for it. That’s what he instilled in me. He was head and shoulders above the other Hammond organ players. And he was always very encouraging towards the others: ‘Yeah, Ginger! Yeah, Jack!’. He’d always be talking it up, saying they were making music for the future. When you stood outside a club where they were playing, the atmosphere was just magnetic.”

McLaughlin was replaced by Heckstall-Smith later that year. With the newcomer blowing sax with gusto and skill, the Graham Bond Organization became a fearsome proposition.

“I got the opportunity to see them play live a lot and absolutely adored them,” recalls Pete Brown, co-author of Cream classics I Feel Free, White Room and Sunshine Of Your Love, and a Bond devotee. “There was nothing like it. It had a lot of the spirit of jazz but with a ferocious energy from blues and rock.”

Jack Bruce: “There was hardly any R&B scene at the time – we more or less invented it. When we started out we’d be doing venues like The Place in Hanley and the Twisted Wheel in Manchester, these real funky little clubs. The audiences went bananas. The kind of stuff we were playing was very new for British music, as was the intensity.”

The Graham Bond Organization’s debut album, The Sound Of ’65, was a stirring attempt to capture the transcendent thrill of their live shows. So finely drilled were they at this point that, according to Bruce, the whole thing was recorded in three hours. The album, a mix of covers and strident original swingers like Half A Man and Spanish Blues, was doubly remarkable for the fact that it was the first British release to feature a Mellotron.

“Way-out blues sounds, weird at times, but always fascinating,” raved the New Musical Express. “Plenty of wailing harmonica and raving vocalistics.”

In July the GBO appeared on ITV’s flagship pop show Ready Steady Go! promoting their new single Lease On Love. Bond delighted in bringing along his new toy, with the Mellotron’s ability to reproduce strings, brass and woodwind sounds essentially putting him at the hub of his own mini-orchestra. He made liberal use of it again on the equally raucous follow-up There’s A Bond Between Us, released later in 1965. But by then it was clear that all was not well.

The GBO were working hard, forever on the road or in the studio, with precious little to show for it.

“Graham’s band flogged themselves to death for very little money and I don’t think they sold many records either,” says Power. “And I hate to say this, but Graham didn’t have the personality or looks that could catch on with a young audience. It must’ve made him unhappy because he thought he’d take the music business by storm when I met him.”

Drugs were starting to derail the band too. Pot had always been a communal form of recreation for the GBO [“We were all stoned out of our bonces,” Bruce admits], but now things had taken a more sinister turn. Both Bond and Baker had become addicted to heroin, making for what Pete Brown calls “the archetypal junkie relationship”. Bond’s burgeoning interest in white magic and the occult only made him more unpredictable. Plus he wasn’t always upfront with the band’s accounts.

“We were playing bigger places but getting no money,” Bruce recalls. “In theory, Graham was paying us. One night at a club in East London, between getting money from the promoter and then crossing the dance floor to pay us, it had disappeared. So he wasn’t being fair, financially. Then Ginger took over as the bandleader, but it only improved a little.”

In fact, growing friction between Baker and Bruce was a factor in the latter being sacked from the GBO in the autumn of 1965. Baker’s departure the following summer was effectively the end of the GBO.

Bond was undergoing myriad changes. He’d left his wife, grown out his hair, taken to wearing multi-coloured cloaks, become fascinated with tarot cards and begun dropping acid. As Baker noted in his autobiography, Hellraiser, Bond “was getting into the realms of the very weird indeed… Gone was the happy musician – he had been replaced by a strange, unsmiling mystic”.

Jon Hiseman was brought in as Baker’s replacement, but the instant impact of Cream had a profound effect on Bond. “What upset him most was the way Jack and Ginger went into Cream and almost immediately had chart singles,” says Hiseman. “Every time he heard one he physically shrank and began to feel endlessly betrayed.

He was becoming increasingly frustrated by the fact that many of the musicians he had worked with on the way up were becoming much more successful than him, and he simply could not understand it. In his self-belief, nobody was as good as he was. And all his pent-up anger was running alongside a serious heroin addiction. A lesser man would have crumbled, but such was the force of his personality, nobody could help. He would just not let you in.”

By 1967, the GBO had split altogether. Hiseman and Heckstall-Smith played briefly with John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers before forming successful prog-jazzers Colosseum. It was a different story for Bond. Immersing himself in occultist lore, he was increasingly prone to bouts of delusion. He began telling people he was the lost son of The Great Beast himself, Aleister Crowley. It was an idea that took hold after Bond read that one of Crowley’s partners had given birth in 1937, the same year he was born, and left the baby in an orphanage. To Bond, a Barnardo’s child who was adopted at six months old, the symmetry made perfect sense.

“He felt that very deeply and would sometimes muse about what his background actually was,” Bruce says. “He thought he was Jewish, for some reason. But he just didn’t know. It must be a terrible thing, to not know who you are. I’m sure it played a large part in the way his life went later on.”

“In the early days he did seem relatively well adjusted,” says Pete Brown, “but when the heroin took hold, he got rather devious and difficult. People who’ve had addictions and manage to stop them find that the ritualistic aspect of it needs to be replaced. So when the smack was gone he felt he needed a power source. But it just became atrophied and went bad. Aleister Crowley just seemed like a fucking creep to me. Graham started off with so-called white magic, then I don’t know where it went. People make some bad choices.”

The remainder of Bond’s career was a procession of ever-diminishing returns. In early 1968 he set out for America, though his failure to secure a work permit put a crimp in his recording plans. Eventually he went into an LA studio and cut Love Is The Law, a pulsating set of organ-led blues, made with Wrecking Crew drummer Hal Blaine, that reflected his spiritual obsessions – the title was one of Aleister Crowley’s occult dictums.

There was also session work for Screamin’ Jay Hawkins and Dr John, the latter’s influence palpable on the gumbo funk of Stiff Necked Chicken, from Bond’s next album for the Pulsar label. Both records offered vivid proof that, no matter how precarious his personal state, Bond’s musical and compositional skills were still intact. Alas, it was a sign of the record company’s indifference that the title of the second LP was misspelt as Mighty Grahame Bond. Neither shifted many copies.

Undeterred, he returned to England in late 1969 and formed the Graham Bond Initiation with his new wife Diane Stewart. Not that it did him much good. Bond was promptly arrested on the eve of a comeback gig and carted off to Pentonville on a two-year-old bankruptcy charge [Jack Bruce would rescue him by paying his bail].

There were two further albums: 1970’s Holy Magick and the following year’s We Put Our Magick On You. The former was an incantatory blow-out recorded with Stewart, who shared his magickal beliefs, that consisted of meditations and rites in Egyptian and Altantean, backed by honking jazz-rock freakery. The sleeve showed the pair, arms raised in supplication, against a druidic backdrop of Stonehenge.

Around the same time, Bond began playing sax in Ginger Baker’s Air Force. The band, which included Steve Winwood, Denny Laine, Ric Grech and Chris Wood, proved too unwieldy to sustain. He also enjoyed a brief tenure as organist in the Jack Bruce Band, although, as Bruce points out, ‘enjoyed’ probably isn’t the right word.

“It was terrifying trying to be the bandleader of Graham Bond,” he winces. “We were playing somewhere in Europe one time and he went out on to the roof. He was in tears about his drug use. He couldn’t seem to get over it. I vividly remember firing him in Milan. He infuriated me so much by playing something or other that I actually ripped a sink off the wall and smashed it on the floor. He was that sort of a guy.”

Bond’s last concerted effort came in 1972, when he and Pete Brown teamed up for Two Heads Are Better Than One. “We had great fun making that record,” says Brown. “Graham was playing really well and we toured a lot. By that time he was a little damaged and addicted to Dr Collis Browne’s [a cough mixture and painkiller], which had opiates in it that you could extract or just down the whole lot. He lived with me for nearly six months, which was kind of difficult. But I loved the guy. I owe him a lot. The great thing about Graham was that he encouraged people. He’d always make you deliver something beyond what you thought you were capable of.”

There were further plans, too, chief among them being Magus, formed with folk singer Carolanne Pegg. But the band split by the end of 1973 without having recorded a note. Bond nevertheless forged a friendship with Magus’s drummer, Paul Olsen.

“My girlfriend and I had a little flat in Barnes, and Graham stayed with us for a while,” Olsen says. “He got arrested for drug possession and spent six weeks at Springfield mental home, this big old Victorian place in south London [it’s thought that Bond had schizophrenia]. They had an old upright piano there that was so out of tune. But I remember Graham sitting there, mapping all the keys in his head, then playing it. He had everybody standing around him, smiling.”

Bond convinced the staff to allow Olsen to bring in the whole band so they could play for the patients. “That gig was incredible. They were the best audience I’ve ever had. There were tears in their eyes.”

Duffy Power recalls seeing Bond at a TV show with Alexis Korner. “Graham couldn’t even get himself a drink,” he says. “I had some pep pills with me, but he wasn’t keen to get stoned like he used to. He was very down.”

Paul Olsen: “He was so depressed at one point that we answered an ad for Chingford Organ Studios, who were looking for a demonstrator. For a man of his history and capability to be reduced to that meant he was at rock bottom. He’d just blotted his copybook with too many people too many times.”

Pete Brown: “Right at the end, Graham said to me: ‘I’m giving all the magic stuff up and I’m just going to play. I’m not going to do anything influenced by that any more’. Then a few days later he was dead.”

There was no evidence of foul play in Bond’s death. Nor was there a suicide note. Some have speculated that he was chased into Finsbury Park station that afternoon by persons unknown, perhaps drug dealers whom he owed money. But with no witnesses coming forward at the inquest, the coroner was left to record an open verdict. It’s most likely that his demise was self-inflicted.

“His death shocked me,” confesses Jack Bruce. “I went to his funeral and played this amazing elegy on the organ there. A lot of people were very moved by it. And I really felt that I was getting messages from him. I felt his spirit and was interweaving a lot of his themes. It was very beautiful.”

Graham Bond was no saint. Even after all these years, Bruce sums him up as “quite a character and quite difficult”. Drug addiction and booze only accentuated his less savoury traits. And, on an altogether more disturbing level, it was claimed in Harry Shapiro’s definitive biography, Graham Bond: The Mighty Shadow, that he even sexually abused his stepdaughter. Bond never admitted it, nor did he deny it. But as a musical entity, his standing among his peers is immense.

“There was never any question about the music,” affirms Bruce. “The Organization was a powerhouse. It was an amazingly hip band for the time.”

Paul Olsen contends that Bond’s over-the-top behaviour and personality were both his biggest weakness and his biggest strength. “A lot of English uptights shunned him. And he was a loose cannon. But people like that enrich lives. When he walked into a room, no one else mattered. He had one of those naturally big personalities. When I first saw him at the Roundhouse in 1970, he was a monster on stage. He had on his robes, his long, flowing things, and all his pentagrams.”

For Pete Brown, Bond’s influence has never waned. “A lot of his showmanship and ideas–the multi-keyboard thing, the things he wore and played – got ripped off by people who made a lot more money. The prog rock people definitely took a lot from him. The GBO weren’t pretty boys preening around – it was real musicians with real soul. Although there were four terrific brains involved, it wasn’t just cerebral music. It was body music as well, powerful and sexy and groovy. And that’s what music should do to you. He was a classic case of someone never fully appreciated in his own time.”

This feature originally appeared in Classic Rock 185, published in July 2013.