Gregg Allman, Cameron Crowe, and ‘Almost Famous’: The Story Behind the Story

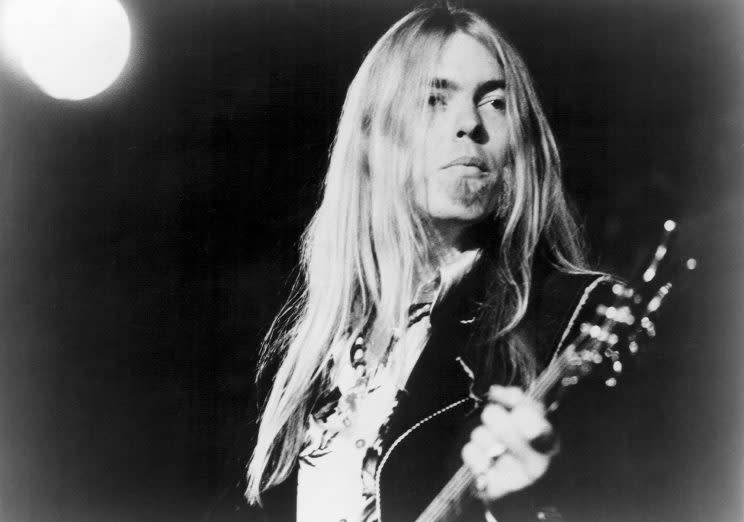

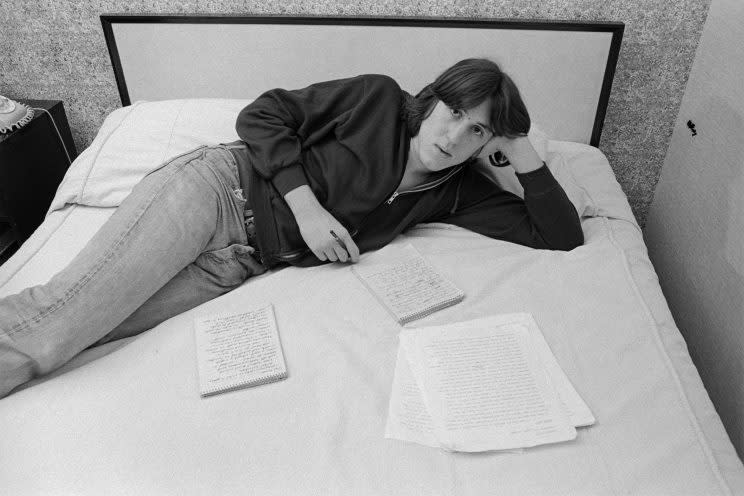

Cameron Crowe had a number of real-life golden gods in mind when he was writing and directing his roman à clef, Almost Famous. Among the rockers Crowe interviewed as a teenager for Rolling Stone whose one-liners were borrowed for the character of Russell Hammond (Billy Crudup) were Robert Plant and Glenn Frey. But it was the late Gregg Allman who inspired some of the fictional musician’s warier or most suspicious traits — including one stranger-than-movie-fiction story that didn’t make it into the screenplay.

Crowe told movie journalist Todd Gilchrist that landing an Allman Brothers Band interview as his first cover story for Rolling Stone when he was 16 “became the basis for much of Almost Famous.” His most memorable takeaway from that experience: “On the eve of leaving the tour with a ton of interview tapes and research, Gregg Allman asked for my tapes back, believing that I was actually an undercover cop sent to spy on the band.”

In the movie, the incident doesn’t get quite as dramatic, but Crowe’s screenplay does have Stillwater’s fictional guitarist suddenly getting paranoid: “Look at him. He’s taking notes with his eyes. How do we know he’s not a cop? He could be selling information!”

Crowe knew that the band was on high alert when he went on the road with them for 10 days in late 1973. Although they were riding high on their most successful album to date, the recently released Brothers and Sisters, the surviving band members were reluctant to spend any amount of time talking about the deaths not that many years earlier of Duane Allman and Berry Oakley. And a previous Rolling Stone feature, written before the deaths, had unabashedly mentioned drug use on the road. So it was Crowe’s fresh-faced persona that won them over, initially.

“Gregg was this towering, suspicious, incredibly vivid guy,” Crowe told Rolling Stone upon the movie’s release. “I finally got him to talk to me because I knew that he thought Jackson Browne was a great songwriter, and that Jackson thought Gregg did the best version of his song ‘These Days.’ So one night in his room, I ask Gregg to play it.” Not only did he get that song, but a lot of others, all on tape. “So I decide I’ve got to get the full story, and I ask him about Duane.”

Gallery: Gregg Allman’s Life in Photos

Allman opened up not only about the loss of his beloved brother — as well as an additional bandmate (Duane Allman and Oakley died in motorcycle accidents a year apart) — but even the tragic murder of their father by a hitchhiker many years earlier. “You’ve got to consider why anybody wants to become a musician anyway,” Allman said, referring to their father’s death as a motivator. “I played for peace of mind.” After the two bandmates passed on in quick succession, it gave Allman a different outlook on their run of hits. “The real question is not why we’re so popular,” he told Crowe. “The question is what made the Allman Brothers keep on going. I’ve had guys come up to me and say, ‘Man, it just doesn’t seem like losing those two fine cats affected you people at all.’ Why? Because I still have my wits about me? Because I can still play? Well, that’s the key right there. We’d all have turned into f***ing vegetables if we hadn’t been able to get out there and play. That’s when the success was, Jack. Success was being able to keep your brain inside your head.”

There was cover-story gold in them thar quotes … until one night, possibly in an altered state, a brooding Allman worried that he’d been too vulnerable, or that Crowe was undercover, or both … and demanded an audience with the teen scribe.

“After the show in San Francisco, Gregg called me up to his room and told me to bring all of the tapes,” Crowe said. “I did, except the one with him singing on it. He answered the door, looking like he was just in another place — ‘f***ed up’ doesn’t do it justice. He looked like he had seen a vision.” Crowe recalled Allman suddenly demanding to see his ID. “Gregg says, ‘Who are you? You’re 16! How do we know you’re not a cop? We could be arrested for having you out here with us. How dare you not tell us your age! You see that empty chair? My brother is sitting there right now, laughing at you!’ I had never been more scared in my entire life.”

Related: Remembering the Midnight Rider, Gregg Allman

Crowe reluctantly turned over the tapes to his rock-star interrogator, and gave editor Ben Fong-Torres a rather dry and surprisingly quote-light cover story. “Ben kept saying, ‘Didn’t more happen?’ I couldn’t tell him — it would have ruined me.” But soon, he said, photographer Neal Preston “called to say the tapes were on their way, and that Gregg didn’t even remember why he had them.”

Shortly before the movie came out, Preston photographed Allman, “and Gregg asked him what ever happened to ‘that guy who was with you when we first met,’” making no connection between the band’s teen interviewer and the filmmaker by then famous in his own right for Jerry Maguire and Say Anything. “Then [Allman] says, ‘We really put that kid through the wringer.’ It really got me, because I had just finished the movie about the kid who gets put through the wringer.”

Related: Musicians React to Gregg Allman’s Death: ‘Words Are Impossible’

But the band members themselves have told different versions of the tale over the years. Allman, long since having made the connection between his 1973 encounters with Crowe and Almost Famous, proudly owned up to being an inspiration for the movie in later years. “That was a bunch of us in there,” he laughingly told Billboard in 2012, when he was promoting his memoir, My Cross to Bear. “Quite a bit. Duane jumped into a swimming pool off a two-story Travelodge in San Francisco,” Allman said, referring to a scene in the movie.

As for the tape-confiscating story, Allman insisted it was a prank, not substance-fueled paranoia. “The one that [Crowe] didn’t put in there [happened] after he did this interview with me and [guitarist] Dicky [Betts],” Allman told the Honolulu Advertiser in 2007. “It was late in the night after the gig. … We stayed up with him till almost the crack of dawn doing this interview. And then we decided after he’d left — about an hour later — to go up and knock on his door and say, ‘Well, look, man, we decided we can’t let you have this much information, so we’re going to have to have [the tapes] back. Of course we were just having fun with him, right? But, oh, man, he looked like he was going to swallow his tongue. We kept ’em for about an hour. And right before he had to leave for his plane, we took ’em back to him.”

So in Allman’s version of the story, the tapes are returned by him, not the photographer, with a hearty laugh before Crowe even has a chance to file his embarrassingly quote-free story to Rolling Stone.

Betts tells it even a little differently. “I talked to Billy Crudup about it, and he said he was playing me,” the guitarist told the Sarasota Herald-Tribune in 2014. With the initial Crowe dustup, “We were writer-shy,” Betts said, “and then Gregg got paranoid and took all of Cameron’s tapes. … And then I went and got the tapes back for Cameron.”

Whatever else may or may not have happened in real life, Almost Famous “was one of the best kinds of authentic rock ’n’ roll movies you get,” Betts avowed. “It’s more like what it’s really like out there than the rest.”

In Crowe’s account, “I left the tour in an emotional mess and wound up catatonic in the San Francisco airport, where I ran into my then-stewardess sister Cindy. She cheered me up and sent me home. Days later, the tapes arrived at my house with an apology note from Gregg Allman. I never told the magazine,” the editors of which were presumably shocked to get a second draft rich with emotional quotes. It didn’t hurt that some of those quotes came not just from the tapes but the letter that accompanied them, which included Allman admitting that he’d been suicidal years earlier, living in California on his own before the Allman Brothers Band got together.

“I had been building up nerve to put a pistol to my head,” Allman admitted in the note, referring to lonely, hard times back in 1969 before a call to join the band “may have saved his life.” Allman was also candid in the Rolling Stone story — which opened with a reverie about the cemetery the band used to hang out in, which inspired the title “In Memory of Elizabeth Reed,” and where Oakley and Duane were buried — about the effect of experiencing band deaths in quick succession. “It was so hard to get into anything after that second loss,” Gregg says. “I even caught myself thinking that it’s narrowing down, that maybe I’m next.”

He wasn’t, of course; there was no band curse after all, as Allman lived another 44 years after that bout of worry and paranoia. If Crowe’s Rolling Stone story didn’t exorcise all the band’s ghosts, it served as a definitive history of the group for many years, freeing them from being tied to the whipping post for too many equally intense interrogations.

And it got Crowe notice among other rock stars as well as in journalism. When a documentary he made about Elton John was released in 2015, Crowe recounted to Interview magazine how Elton “threw a party for the opening of his (Rocket) label in L.A., and he said to me, ‘I know who you are. I just read your cover story on Gregg Allman. It was cool. You really caught Gregg Allman. I love the Allman Brothers Band.’” Best of all, they got to skip over the phase where Elton might’ve worried that Crowe was a narc.