‘The most expressive face I’ve ever seen’: Tony Hancock at 100, by Diane Morgan, Paul Merton and more

‘When I was 12, my father introduced me to Tony Hancock,” says Diane Morgan, AKA Philomena Cunk. “Not literally, of course! He said, ‘Sit down and watch this. You’re going to love it.’ And I did. I could not believe how funny this man was.”

Morgan is far from alone among her fellow comics in revering Hancock, who was born in Birmingham 100 years ago today. Indeed, many will tip a battered Homburg in homage to the comedian whose disgruntled DNA can be detected in later sitcom characters from Captain Mainwaring to Basil Fawlty – and possibly even Hyacinth Bucket. It doesn’t end there: the Tony Hancock Appreciation Society is going from strength to strength; over the past few years, membership has swelled by 50 per cent. “Stone me,” as Hancock himself might have said.

But why? Hancock died in 1968; his TV shows are seldom repeated, his films are rarely shown. Books have been written and documentaries made in an attempt to unearth the secret of his comedy genius. Indeed, even Hancock became obsessed by the quest. “He was never satisfied with being a funny man,” his friend Harry Secombe once said. “He needed to know why.”

Hancock was neither slapstick comic, nor gag merchant. “And he was a terrible stand-up,” fellow devotee Paul Merton tells me. (Although one joke from his early stage act is fondly remembered: he would bounce on in top hat and tails and call back into the wings, “Put the Rolls in the garage, George – I’ll butter them later.”) But he possessed that ineffable talent to amuse, what they call in the business “funny bones”. It eludes definition – like star quality or sex appeal – yet, when you encounter it, it’s unmistakable.

“I have seen a lot of TV comedians, both here and in America, but Hancock at his best soared high above them all,” wrote that connoisseur of comedy, J B Priestley. “We might almost say that he existed in an extra dimension. Hancock was something else – an artist.”

Hancock belonged to that brave cohort of post-war comics who had begun by entertaining the troops, a generation that also included all four future Goons: Peter Sellers, Spike Milligan, Harry Secombe and Michael Bentine. “That was one of the very few upsides of fighting a world war,” Clive Anderson, another of Hancock’s famous fans, tells me. “A lot of performers got their first break in the Armed Forces.”

Next came another ordeal by fire, playing the Windmill Theatre in Soho, where so-called “Revudeville” performances ran from lunchtime to just before midnight, six days a week, for a six-week run. Variety acts and comedians had the thankless job of keeping punters amused between glimpses of the main attraction: girls, girls, girls.

Later, Hancock would remember the experience with a rueful smile. “You learnt to die like a swan, you know – gracefully,” he said. In fact, he fared relatively well at the Windmill, certainly better than a northern double act called Bartholomew and Wiseman, which only survived a week; though later, they’d find fame as Morecambe and Wise. Hancock soon acquired an agent who secured him some radio broadcasts, leading in turn to better bookings on stage. By 1952 he was starring in London Laughs at the Adelphi with Jimmy Edwards and Vera Lynn.

On the wireless, Hancock featured in a 1951 series called Happy Go Lucky. Lucky it was indeed – because that’s where he first encountered Alan Simpson and Ray Galton, two brilliant young comedy writers who would custom-build a vehicle for his unique talent. Launched in 1954, Hancock’s Half Hour became one of the BBC most popular comedies, running for more than 100 episodes.

Their idea was to get away from the standard format of an opening monologue, some sketches and a song or two. Instead, they wanted a story-driven situation comedy, without “jokes” per se, in which the humour came from the characters. The persona they developed for their star was Anthony Aloysius St John Hancock, “a shrewd, cunning, high-powered mug”. This grandly named individual lived not in a stately home but in shabby post-war austerity at 23 Railway Cuttings, East Cheam.

Galton and Simpson transmuted elements from Hancock’s own personality into the character he played. As Hancock told an interviewer, the role wasn’t “a character I put on and off like a coat. It’s a part of me and a part of everybody I see.” In a typical episode, Hancock’s lofty aspirations – his “delusions of adequacy” – were continually upended by reality. And also by his friendly nemesis, Sidney Balmoral James, whose dodgy get-rich-quick schemes invariably left Hancock holding the baby.

Sid James was first among equals in a wonderful supporting ensemble. In the early shows, Hancock had a girlfriend. But as his character developed – displaying a marked lack of success with women – the feminine touch was provided by Hattie Jacques as Griselda Pugh, Tony’s housekeeper-cum-secretary. Bill Kerr was the lovable dumb lodger. And Kenneth Williams, with a glorious profusion of character voices, played almost everyone else.

Paul Merton recalls buying a big old reel-to-reel tape recorder from a school friend so he could record repeats of Hancock episodes. Holding the microphone up to the radio, he implored his family to keep quiet for those magical 30 minutes, “And then it was marvellous to be able to hear the shows over and over again,” he tells me.

In 1956, while the smash-hit show continued on radio, a parallel television series of Hancock’s Half Hour was launched on the BBC. Hancock’s transfer to TV was boosted immeasurably by the fact that, as Simpson put it, “Tony looked like he sounded.” Listeners were delighted to find him just as funny on the small screen – if not even funnier.

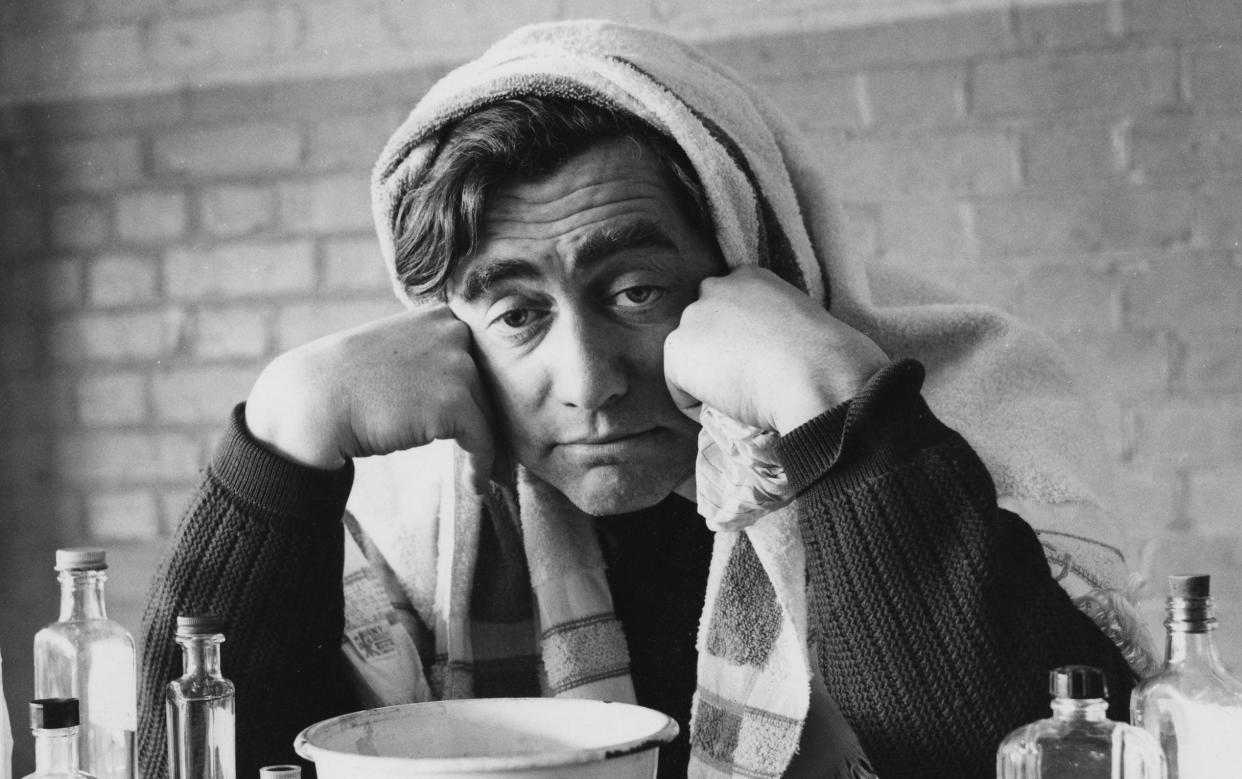

“It annoys me when people refer to Hancock as a deadpan comedian,” says Morgan. “Actually he’s got the most expressive face I’ve ever seen. He can go through 30 different expressions in one five-second clip … I watch him even now and he really cheers me up, more than any other comedian.”

Before advances in recording technology, Hancock’s Half Hour was transmitted live, leaving no opportunity for retakes or editing. It took five days to prepare each 30-minute show, then a day for camera rehearsal and the live broadcast, followed by a booze-up at the pub and a day off to nurse the hangover before starting on the next episode.

TV’s cumbersome technical demands also meant fewer set-ups and a smaller cast. By then, Hancock was tired of Williams’s funny voices and catchphrases (“Stop messing about!”), which he viewed as cheap laughs, and Galton and Simpson shared his desire to move ever further towards pure character comedy, at which Hancock excelled. So the East Cheam ensemble was disbanded, leaving only James as a regular co-star.

Anderson points out that, over their 10 years together, “the writers and actor grew into each other. And the scripts became increasingly realistic as Galton and Simpson burrowed into Hancock’s own insecurities.” Before long, Hancock opted to move away from East Cheam completely and, at his instigation, even James was given the heave-ho.

According to Simpson, “We thought, right then, if Tony wants to go it alone, then how about this?” And they wrote him an extraordinary tour-de-force: The Bedsitter, or Hancock Alone. It was just that. Hancock, now living in an Earl’s Court bedsitter, completely alone throughout the episode, in continuous real-time. It was a solo performance of remarkable subtlety, power and skill; a masterclass in comedy writing and acting.

Now entitled simply Hancock, the seventh TV series – which also included the fondly remembered episodes The Blood Donor and The Radio Ham – was a triumph. But it would also prove to be Hancock’s last series for BBC television. By now, he had set his sights on international stardom, and he knew the key to worldwide success lay in film.

Thankfully, his first starring movie, The Rebel (1961), was again written by Galton and Simpson. And the character he played was – again – Tony Hancock, disgruntled, vain, aggrieved and bombastic. To Hancock’s army of fans, it felt like a gift: a full-length feature film! And in colour! We’d only ever seen him in black and white.

He looked terrific. There was top-notch support from comedy veterans such as Dennis Price and George Sanders and familiar faces from Hancock’s TV shows: Irene Handl as his landlady, John Le Mesurier as his bemused boss, Liz Fraser as a waitress. Plus a seasoned comedy director, Robert Day, whose credits included The Green Man with Alastair Sim and Two-Way Stretch with Peter Sellers.

Hancock plays an office worker who throws up his dull City job to become an artist in France. It develops a theme from one of his TV episodes: “Why is the public so slow to recognise genius? … It just comes natural to me – I was born with it … well, I was as good when I was four as I am now.” Lucian Freud declared The Rebel the best film about modern art he’d ever seen. The film was a hit in Britain, and Hancock was nominated for a Bafta. But in the US, the critics detested it. “Norman Wisdom can move over,” sneered The New York Times. “The British have found a low comedian who is every bit as low as he is, and even less comical …”

The studio quietly backed out of their deal to make more films with Hancock. His American dream had been dealt a mortal blow.

At the same time, Hancock’s private life was plunging into chaos. He had become increasingly reliant on alcohol, and it was now visibly affecting his work. His first marriage ended very publicly in domestic violence and divorce, the second soon headed the same way, and he’d alienated virtually all of his friends in the profession.

Hancock was now set on a lonely path. Questing ever further for realism, and for success in America, he decided to work with a new writer: the critic and journalist Philip Oakes, who had interviewed him for the magazine Books and Arts. Thus Hancock came to appear in a rather bleak film called The Punch and Judy Man (1963), playing a washed-up seaside entertainer whose marriage is falling apart.

Paul Merton remembers watching the film with his mother, who was scandalised when Hancock made a very rude gesture. The fans were disappointed, bewildered even, by this mournful study of a disintegrating marriage, with very few laughs. As Merton says, “It was basically a tragicomedy – but without the comedy. Very bitter.”

As well as being the star of the film, Hancock was also co-writer, co-producer and one of its financiers, so he was carrying an enormous burden throughout the production. The young director Jeremy Summers, fresh from television, had little experience of comedy or feature films. As Hancock’s widow Freddie told me: “Tony wanted more control of his career. But the more control he got, the less career he had.”

In the years that followed, Hancock was offered cameo roles in two period romps. In Those Magnificent Men in their Flying Machines (1965) he popped up as a pilot with an ingenious wheeze to win the 1910 London to Paris air race. In order to minimise air resistance, he would fly his plane backwards. (That was just about the best joke in the film.)

Next, The Wrong Box (1966) was a frenetically unfunny “caper” movie, featuring just about every comedy actor in England. Writer Harry Thompson called it “a classic example of the British film industry’s tradition of applying famous comedians en masse to a feeble script in the hope of papering over any cracks”. Larry Gelbart, of M*A*S*H and Tootsie fame, who co-wrote the film, told me, “Tony had that rare quality – an antic spirit. He shared this with Jack Benny. It’s partly a physical quality but more, I think, a metaphysical quality. They have an aura – something that goes before them, so the audience just knows they’re funny, even before they open their mouths.” It was always a joy to see Hancock on the big screen, in anything. But sadly, there would be no more films for him.

There had been signs of his troubled state of mind all through his career. Back in 1960, he’d been interviewed by John Freeman for a heavyweight TV series called Face to Face. It was more of an interrogation than an interview: he was questioned rather aggressively about his finances (“It’s said that you earn £35,000 a year …”), his religious views, his relationships, and most persistently of all, whether he was happy. “I wouldn’t expect happiness,” Hancock replied. “I don’t think it is possible … The only happiness I could achieve would be to perfect the talent I have, however small it may be … If the time came when I found that I had come to the end of what I could develop out of my own ability, limited however it may be, then I wouldn’t want to do it anymore.”

There were some unsuccessful comeback attempts on commercial TV, and theatre gigs including a disastrous one-night-stand at the Royal Festival Hall. But Hancock was very popular in Australia, and he was invited out there to film a comedy series in 1968. Very sadly, during production, alone in a hotel room, at the age of 44, he took his own life.

As Barry Cryer would later put it, “Tragically, first he got rid of his co-stars, then he got rid of his writers, and finally he got rid of himself.” To his old friend Harry Secombe: “Tony Hancock was one of those rare ones who are bedevilled by success … The demands of his profession shaped him, destroyed him and eventually killed him. But he served it well. If anyone paid dearly for his laughs, it was the lad himself. May he lie sweetly at rest.”

For further details about the Tony Hancock Appreciation Society, see: tonyhancock.org.uk; 79 episodes of Hancock’s Half Hour are available on BBC Sounds