“As hard as it was, and it was hard, nobody wanted to bottle out. We just knew we had a big landscape we could explore”: How Tales From Topographic Oceans became the most arduous project in Yes’ history

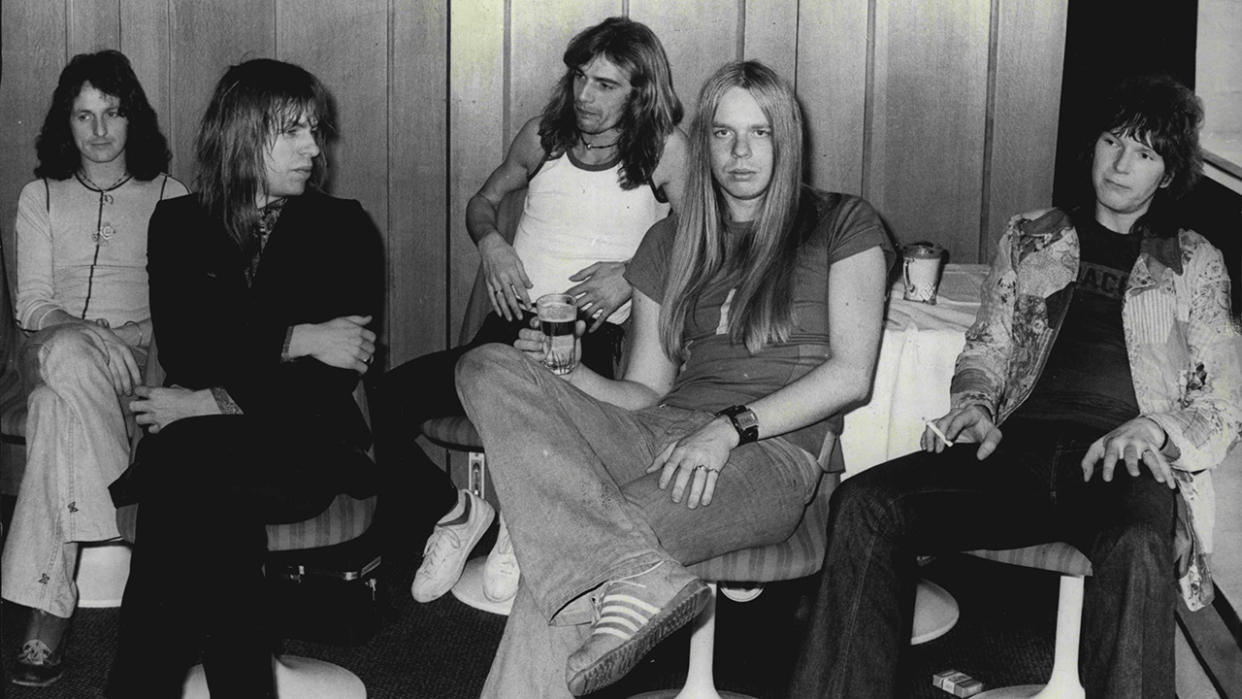

In 1973, Jon Anderson sold Steve Howe an idea he’d come up with from the pages of a guru’s memoir. The result was sixth Yes album Tales From Topographic Oceans – a four-sided release containing just four tracks. In 2016 Prog explored the determination it demanded of the band members, and the price they paid to deliver it.

“I actually wanted to record Tales From Topographic Oceans in a tent in this beautiful wood that I’d found, miles from anywhere. I thought we could bury a generator 300 yards away under the ground so we could have electricity in the tent. We’d be able to record there and have all these natural sounds around us. That’s where my brain was at at that time. Of course, they thought I was totally crazy!” laughs Jon Anderson.

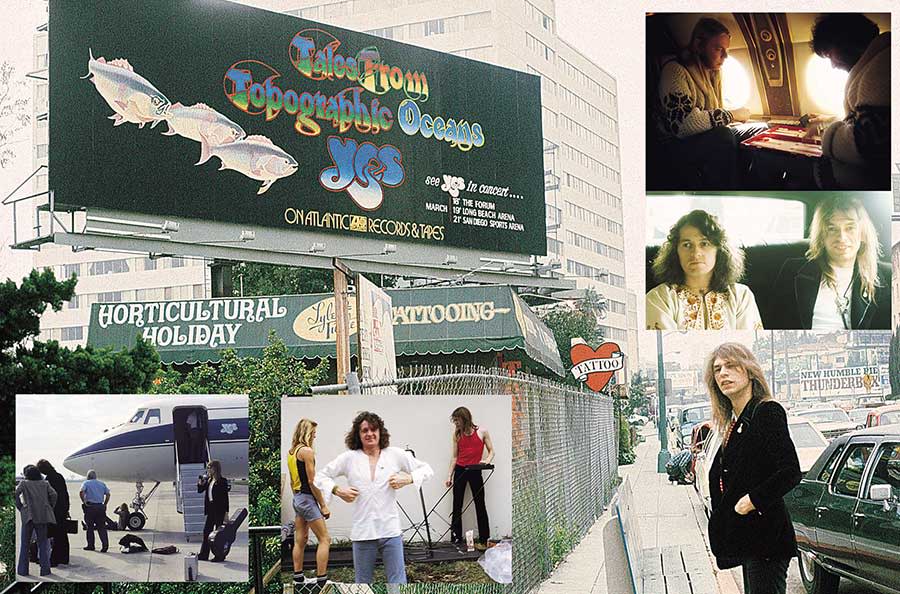

“Crazy” turned out to be one of the nicer things said about the sixth Yes studio album upon its release in December 1973. Although achieving Gold status on both sides of the Atlantic, it received a mauling from many critics. When the band played the four-sided opus live, many fans found it a challenge. But challenge is exactly what Yes thrived on. Always a band on a mission and in a hurry to push forward, they were keen to do whatever was in their power to be at the forefront of a musical movement where nothing that was worth anything stood still for very long.

Chris Squire observed that the build-up to Tales… had been going on for some time, with Heart Of The Sunrise marking the realisation of an ambition to produce something on a much bigger scale. With Close To The Edge, they went bigger still. An epic release, it meshed adventurous solo excursions with tightly knit arrangements. The punch Yes delivered came not from a single source but rather their collective force. Anderson was determined their music should avoid showboating licks for their own sake. “There were a lot of bands up there soloing forever but that wasn’t what I wanted to do. I wanted to create music that had length and breadth and adventure, that would carry the audience through this experience. With lights and staging, you could take them on a journey.”

They say a journey of a thousand miles begins with a single step. Tales From Topographic Oceans began with a single conversation between two characters at very different ends of the musical spectrum. In Bill Bruford’s London flat in early March 1973, along with dozens of other friends celebrating the drummer’s wedding earlier in the day, Anderson sat perched on an open windowsill talking with Jamie Muir. “He was an unbelievable stage performer,” says Anderson of the eccentric King Crimson percussionist, known at the time for wearing bearskins, spitting blood capsules from his mouth and flailing his percussion rig and packing cases with heavy chains. “I wanted to know what made him do that; what had influenced him.”

Muir enthused about Autobiography Of A Yogi by Paramahansa Yogananda. The late guru was well-known in esoteric circles, and had made a more secular cameo appearance on the cover of The Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, wedged between HG Wells and James Joyce. Reading Yogananda’s words, Muir told the singer, had had a profound impact upon him. “He said to me, ‘Here, read it,’ and it started me off on the path of becoming aware that there was even a path,” says Anderson. “Jamie was like a messenger for me and came to me at the perfect time in my life… he changed my life.”

It was powerful stuff. Reading the book prompted Muir to quit music and become a Buddhist monk, and while the effect upon Anderson may not have been so extreme, it was the catalyst that took Yes into uncharted waters.

Discovering a reference to the different levels and divisions within Hindu scriptures in a footnote led to a ‘Eureka!’ moment for Anderson as the group toured Japan. Convinced he’d found the structural framework within which to place the large-scale ideas and concepts he’d been mulling over, he found a willing ally in Steve Howe. Having written Roundabout and Close To The Edge together, there was a real bond between the pair.

“We were really up for the big, challenging things like, ‘Let’s do an album with four Close To The Edges,’” laughs the guitarist. Over several post-gig evenings in candlelit hotel rooms, locked away from all the usual distractions from life on the road, they trawled through a huge accumulated array of musical sketches and motifs, searching for pieces to complement Anderson’s thematic ideas.

“I’ve a lot of cassettes of Jon and I sitting in places like New York or Cincinnati recording songs,” recalls Howe. “Jon would say to me, ‘What have you got that’s a bit like that…’ so I’d play him something and he’d go, ‘That’s great. Have you got anything else?’ and I’d play him another tune. I notice that one of the pieces he turned down early on eventually became part of side three. He heard it later and said, ‘That’s a good piece,’ because we were looking for something different then.”

At the end of a marathon all-night writing session in Savannah, Georgia, the basic themes and broad outline of the next Yes project had finally coalesced. Alan White recalls them presenting their deliberations to the rest of the group. “I thought it was great. The band wanted to make a big statement here worldwide. We had this whole story, you know? I wanted to create music that had length and breadth and adventure that would carry the audience through this experience.”

Howe remembers a slightly more cautious reception. “Some guys in the band were like, ‘Hold on a minute.’ They were fine with a double album but were, you know, ‘Just four songs?’ But Jon and I did manage to sell the idea.”

Some guys in the band were like, ‘Hold on a minute.’ They were fine with a double album but were, you know, ‘Just four songs?’ Jon and I did manage to sell the idea.

If the starting point of Tales… had come about when the paths of Yes and King Crimson had accidentally crossed at a party, the next stage in the story found Yes indebted to another part of the prog spectrum: Emerson Lake And Palmer and their Manticore Studios, based in an old converted cinema in Fulham. Over several weeks in the summer of 1973, occupying the main stage at the rehearsal complex, they got to grips with fragments, sketches and outlines. In some respects, this was business as usual for the group. Countless times in their history, Yes had sewn together different musical elements – never the easiest of jobs

The arrival of Rick Wakeman in 1971, who understood the nuts and bolts of the music, had improved the pace with which loose ends and threads might be put to use or dispatched. If things weren’t quite so quick this time, it came down in part at least to the sheer scale of the task. Nailing one track can be hard enough. Trying to map out four, each lasting the side of an album, was enough to give even the most enthusiastic in the band pause for thought. The logistics of creating a piece that would go through several distinct transformations over 20 minutes was a formidable prospect even for a group with Close To The Edge under their belt.

Likening the process to climbing a mountain, Anderson argues, “Sometimes you need someone to say, ‘This is where we’re going to go; we’re going to make it, we’ve done it before. Don’t worry, it’ll be okay.’ If you wait for everyone else to arrive at a decision, we’d still be climbing the mountain!”

He readily admits he was frequently overbearing during the writing and rehearsals, chivvying his bandmates along, trying to keep people focused. “So many things happened in that two-and-a-half-month period. In rehearsal I tended to know exactly where we were going, to a point. I knew there were going to be some solos from Steve, and in the first movement there were solos from Rick, and in the second movement. In the third movement there’d be solos from Chris and, especially the fourth movement, a lot of drums. I had such great faith in doing it.”

It was a collection of lots of pieces of music that we had carrying the story. We had to find a way of joining the jigsaw puzzle together to make it work

That faith was something shared by Howe. It was tough going, he admits, but there was a sense that there lay an unprecedented opportunity before the group, provided they were able to keep their nerve. “As hard as it was, and it was hard, nobody wanted to bottle out of what we’d committed ourselves to do. We just knew we had a big landscape we could explore. Side one set the scene so much. It was showing that we wanted to use some themes but use them in different ways. It was quite plain what we were doing.

“By the time we got to the second side, I think we really wanted to go off somewhere else altogether if we could. There’s folky bits where I’m playing lute and we got very light and spry, which is its own dynamic. We could really stretch out; and no less so than on side three, when most of the beginning is a stretch-out of some mad, really quite wacky ideas – some quite Stravinsky, some quite folky. With Leaves Of Green you get back to the roots of our music. There’s almost a Renaissance period that we play at the end of side three. To close, we had to do something that was going to be bigger than big. We felt that with what we had constructed we had a beautiful song, Nous Sommes Du Soleil, and there was a use of theme again that we did nicely, I think.”

Anderson recalls being eager to get started as early as possible because they had so much to get through, though not everyone in the group shared that particular body clock. “It’s a known fact that Chris Squire never wanted to play music before midday,” laughs White [who died in 2022]. “We’d spend all day going over things and we’d get to dinner time and then get some rest. There was some trial and error initially. It was a collection of lots of pieces of music that we had carrying the story. We had to find a way of joining the jigsaw puzzle together to make it work.”

With much of that puzzle now in place, albeit somewhat loosely, Yes transferred to Morgan Studios in Willesden. Its urban location, on a busy road with heavy traffic, was about as far away from the countryside idyll Anderson had originally envisaged as you could get. On the plus side, it boasted a 24-track desk that was more than capable of containing the band’s expansive musical ambitions. And that lack of bucolic charm? Well, Rick Wakeman had the answer.

“One day Rick was in a particularly funny mood, which is not hard for Rick – he used to play jokes on everyone,” reveals White. “He said he wanted some cows in the studio. He had a cardboard cutout cow at one end of Morgan Studio, so we all said we didn’t mind. Then he brought some palm trees in. I was like, ‘Okay Rick, have you finished decorating ?’ ‘It’s a nice environment now,’ he said, and I went, ‘Okay, I can live with that…’”

As an indicator of how strange things had become, White also remembers a shower cubicle complete with tiles being built inside the studio in order to try to replicate the sound Anderson heard when he was singing in the shower at home.

Ask any musician about their ambition and the opportunity to make a record will be pretty high on the list. All the players in Yes had been there and done that several times over. As seasoned and successful professionals, there was no naivety about what was involved. They’d experienced the nitty-gritty of putting records together. Yet this time it was different. Every day, as each of them drove from home to the studio, the distance between what Anderson and Howe had outlined and the reality of what was going onto tape gnawed at their confidence. Of course, other sessions hadn’t always been plain sailing, but nobody in the band was quite prepared for how choppy the waters had now become.

Squire [who died in 2015] recalled in 1992 that despite the cardboard cows and DIY plumbing, there was little in the way of levity. Journeying deeper into the making of the album, he and Anderson were bumping heads. “At that time, Jon had this visionary idea that you could just walk into a studio and if the vibes were right, the music would be great at the end of the day… which is one way of looking at things! It isn’t reality. It took a lot of Band-Aids and careful surgery in the harmony and embellishment department to make it into something.”

Wakeman’s musical skills and flair for arrangements had been heavily utilised throughout the making of Fragile and Close To The Edge. However, changes in the personal and social interactions between the band took their toll in the confines of Morgan. As the construction of the vast musical edifice continued, the personal harmony prevalent on other albums was now rather elusive. Speaking in 1995, co-producer Eddy Offord commented on the rift that opened up during the recording. “At that point it was obvious that Rick became really much more outside the rest of the band. It wasn’t so much musical direction… If you want the honest truth, it was the fact that the whole band was into smoking dope and hash and Rick was into drinking beer. He never touched pot. I don’t know what it was, but he was on the outside.”

Yet there was perhaps another, more significant factor. The phenomenal success of Wakeman’s solo career with The Six Wives Of Henry VIII had created its own momentum and, not unreasonably, there was demand for a follow-up. As Tales… slowly progressed during the summer and early autumn, Wakeman, when not supplying keyboards to Black Sabbath in the adjacent studio, was also busy scoring his next solo project, Journey To The Centre Of The Earth.

Yes was heading towards avant-garde jazz rock and I had nothing to offer there

Anderson, believing that these extracurricular activities were distracting and preventing Wakeman from contributing to the full extent as he had done on previous recordings, was in little doubt as to what the priority should have been. “My feeling was, ‘Why don’t you put that music into this project, into Tales…?’ We had a couple of times when Rick said, ‘Well, I’m doing what I want to do,’ and I was like, ‘Okay, well, I’ll just get on with it.’”

For his part, Wakeman had genuine misgivings about the general direction of the material. “Yes was heading towards avant-garde jazz rock and I had nothing to offer there,” he observed in 1974. “We had enough material for one album but we felt we had to do the double.”

Marshalling both music and esoteric concepts into a series of cohesive suites required a kind of commitment that was beyond their usual experience, says Howe. That some were struggling was, of course, a cause for concern but, he argues, the way around that was to overcome the doubt by diving in. “You could say to another member, ‘Well, you don’t like this bit but have you got a part worked out yet? Because if you find a part, you’ll get involved in the music!’ Jon and I sometimes really had to spur the guys on.”

A byproduct of Wakeman’s absences was to create a space for others to fill. White recalls sitting at the piano and coming up with the chords that would be used for the ‘Hold me my love’ bridge on Ritual. On another occasion, the drummer sat tinkering with a guitar, working out some chords. They captured Anderson’s attention as he strolled past. “Jon said, ‘Show me those chords,’ and then he took it over,” resulting in the chord sequence being added to The Remembering.

A hungry beast, Tales… called upon all of their songwriting resources, meaning that many items that had been discarded from their previous writing sessions were now re-examined and press-ganged into service. Some, such as the Young Christians theme that appears on side one, dated as far back as Fragile. Back then the passage had been given a much rockier treatment but had ultimately failed to find a suitable home. At this point, necessity demanded it be piped aboard the good ship Topographic.

The clock was ticking. A UK tour was already advertised for November and December. Factory time for pressing of the album was already booked. Every hour that swept by in the studio not only broke down into minutes and seconds but pounds and pence as well. “God bless Eddy Offord,” laughs Anderson, referring to the period when the pair were literally camping out at Morgan Studios as they worked around the clock, even sleeping there in order to cross the finishing line as mastering and manufacturing dates loomed.

“In those days it was like rolling the dice, whether you could mix it well on the first take or the 20th take. There’s a classic photograph of all of us on a fader. It was crazy but what happened was we would mix in sections: two minutes, one minute, four minutes and so on. Then we’d have the quarter-inch tapes hanging from the wall and Eddy would then stick it together with Sellotape and that was how we made albums in those days. There was no automation or click tracks.”

Perhaps not surprisingly, remixing the album in 5.1 surround sound was no easy task for Steven Wilson. Despite having so many previous surround sound remixes of classic material under his belt, he recalls how daunting it was to delve into the source tapes and make sense of what were in effect micro-managed moments and decisions taken on the fly 43 years ago.

“Even though it was recorded on 24-track, the complexity of the music and arrangements meant that every inch of tape was crammed with overdubs. One channel on the tape might start off as vocals, but then switch to a percussion overdub, then a lead guitar phrase, then some mellotron, et cetera. In order to have maximum control over the mix, and to be able to give each sound its own space and treatment, I had to identify and break every element out onto its own channel. This meant that one side of the original album could extrapolate out from 24 channels to 50 or 60 individual parts. Actually, I think side four ended up being more like 100!”

We started to drive with all the tapes still on top of the car… That was our wild experience of making this album – we nearly had it crunched under a double-decker bus!

Although they’d always built their albums from a patchwork quilt of takes, Tales… had without doubt been the most arduous recording in the band’s career. The grand themes and vistas, meticulous sonic sculpting and textural details embedded into the album hadn’t come easy, and nor did the completion of the record. With mastering and manufacturing deadlines looming, as Anderson and Offord sat bleary-eyed after the final overnight mixing session, their sleep-deprived state caused a last-minute drama that came perilously close to farce.

“At about nine in the morning, me and Eddy packed up the tapes and went to our car and he put the tapes on the top while he found the keys,” says Anderson. “Then we got in and started to drive toward the main road with all the tapes still on top of the car, making them slide off into the middle of the road. There was a big, red double-decker bus coming towards us and I ran out and stopped the bus [laughs]. That was our wild experience of making this album – we nearly had it crunched under a double-decker bus!”

The true extent of Wakeman’s antipathy towards Yes’ music became obvious early on in the UK tour in November 1973. “I remember we played the whole thing in its entirety at The Rainbow and he wasn’t happy,” says White. “It kind of went downhill from there.”

Wakeman’s growing disenchantment would famously manifest itself in eating curry on stage during Tales… and though it became something of a running joke, it was in truth an expression of his boredom and a protest of sorts. Looking back, White feels a sense of disappointment at the rift between Wakeman and the rest of the band.

“For some reason Rick couldn’t get his head around what we were doing but he played all the parts and he was great. He’s just an amazing keyboard player. But he couldn’t see where the band was going. He felt he wanted to move in his own direction.”

Even some of the band’s long-term supporters in the press at the time baulked at a record that had slipped far from rock’s usual moorings. With this double album, the argument went, they had overreached. Wakeman’s oft-quoted assertion that the album suffered from too much padding because of a lack of real musical substance became received wisdom in discussions of the band’s work. In later years it was routinely cited as evidence of prog rock’s over-indulgence, with sceptics pointing to its 80 minutes as proof of hubris and artistic extravagance.

When Yes went off the road in January 1974, Wakeman staged and recorded Journey To The Centre Of The Earth. Shortly after its release in May ’74, it topped the album charts. Hearing the news on his 25th birthday, Wakeman rang in his resignation from the band on the same day. Anderson recalls the recriminations following Wakeman’s departure. “Management and the record company were saying, ‘Why didn’t you just do another Fragile?’ I just had the feeling that if we don’t try something in this lifetime then, okay, we’re just rock stars, and I personally don’t think that way… You’ve got to do things that are a little bit different in this lifetime. And when you have the chance to do it, you have to jump in that water and enjoy it.”

For Howe, the album remains an important milestone in the Yes story. “It was a time of spreading our wings, a wonderful project where we went to the end of the earth to do it. There was often a feeling that disaster was almost about to strike, but we got there in the end. You have to account for Tales… in our history to properly talk about what Yes achieved because it was quite exceptional. I don’t think we’d be the same group without it.”

In 2016, as Yes toured America, The Revealing Science Of God and Ritual resurfaced. “Going on the road playing side one and side four is really nostalgic,” says White. “We made a great career of really adventurous material that was trying to move music in a good direction. Side one is a difficult thing to play and side four, you’ve got the whole Ritual thing at the end, which is quite a thing to put together, where you’ve got the drums playing the lead melody. We had a theme running through the album, recurring though different songs, and it culminated in the whole band playing the melody on drums, all of us at the same time. I’m really looking forward to playing it live again.”

Tales From Topographic Oceans is an album you can’t be ambivalent about. Asked if it’s a formidable achievement or a folly, Steven Wilson says, “Both! One of the things I miss in modern rock music is the will to reach for the stars and risk falling flat on your face. Conventional wisdom might be that with this album Yes roundly achieved the latter, but I’m happy to see a growing number of those like me that appreciate its beauty and ambition. Even when the ideas perhaps aren’t entirely coming off, I still admire and enjoy the sheer uncompromising strangeness of it. It doesn’t have the immediacy of some of Yes’ other records of the era, but I think, given time, it reveals itself as perhaps their greatest musical statement of all. It’s pure hardcore Yes!”