"In our haste, the lump of hash got away and slipped down the sink drainpipe. Panic!": What happened when Jimi Hendrix created havoc and got banned by The BBC

On January 2 1969, the Jimi Hendrix Experience flew into London from New York for a European tour that would start with a TV appearance on BBC1’s Happening For Lulu show. The band had spent virtually the whole of 1968 in America, and had played just one British show, at the Woburn Festival in July.

It was something Hendrix felt a little embarrassed about, jokingly offering to buy everyone in the country a drink, according to one reporter who interviewed him on the afternoon before the show on January 4.

The band seemed in good spirits, although with bassist Noel Redding in the process of forming a side project, Fat Mattress, there were rumours that he was not entirely happy in the Experience. It was known that he was feeling some frustration, having been a guitarist before joining them on bass. His commitment to the Experience had also been questioned during the recording of Electric Ladyland, which had been released in October 1968. He had failed to show up for some sessions, and Hendrix had played bass on a couple of tracks, although he had still been allocated his own track on the album, Little Miss Lover. But there was no disharmony evident as they chatted to journalists while waiting to perform at the BBC's Television Centre in west London.

Happening For Lulu was BBC1’s primetime Saturday Evening show, broadcast live before the six-o-clock news in black and white – BBC2 had started broadcasting in colour in 1967, but BBC1 would not follow suite until November 1969. Hendrix would play two songs, starting with Voodoo Child (Slight Return) from Electric Ladyland. The show’s producer, Stanley Dorfman, then wanted Hendrix to play Hey Joe, even though All Along The Watchtower had been a Top 5 hit just a month earlier. Hendrix was not happy, feeling that Hey Joe, which had been released over two years earlier, was something of a backward step that did not represent where he was now.

But the producer insisted, perhaps believing that after such a long time away Hendrix needed to play something a family audience would recognise. There was also talk of Lulu joining in for a duet on the last verse, although no definite plan appeared to have been reached when the group rehearsed their spot earlier in the day and camera positions and angles were worked out. The band then retired to their dressing room and, to pass the time or maybe assuage Hendrix’ grumpiness at having to play Hey Joe, they decided to smoke the lump of hash someone had thoughtfully provided.

As drummer Mitch Mitchell recounts in his autobiography: “In our haste, the lump of hash got away and slipped down the sink drainpipe. Panic! We just couldn’t do this show straight. Anyway, I found a maintenance man and begged tools from him with the story of a lost ring. He was too helpful, offering to dismantle the drain for us. It took ages to dissuade him, but we succeeded in our task and had a great smoke.”

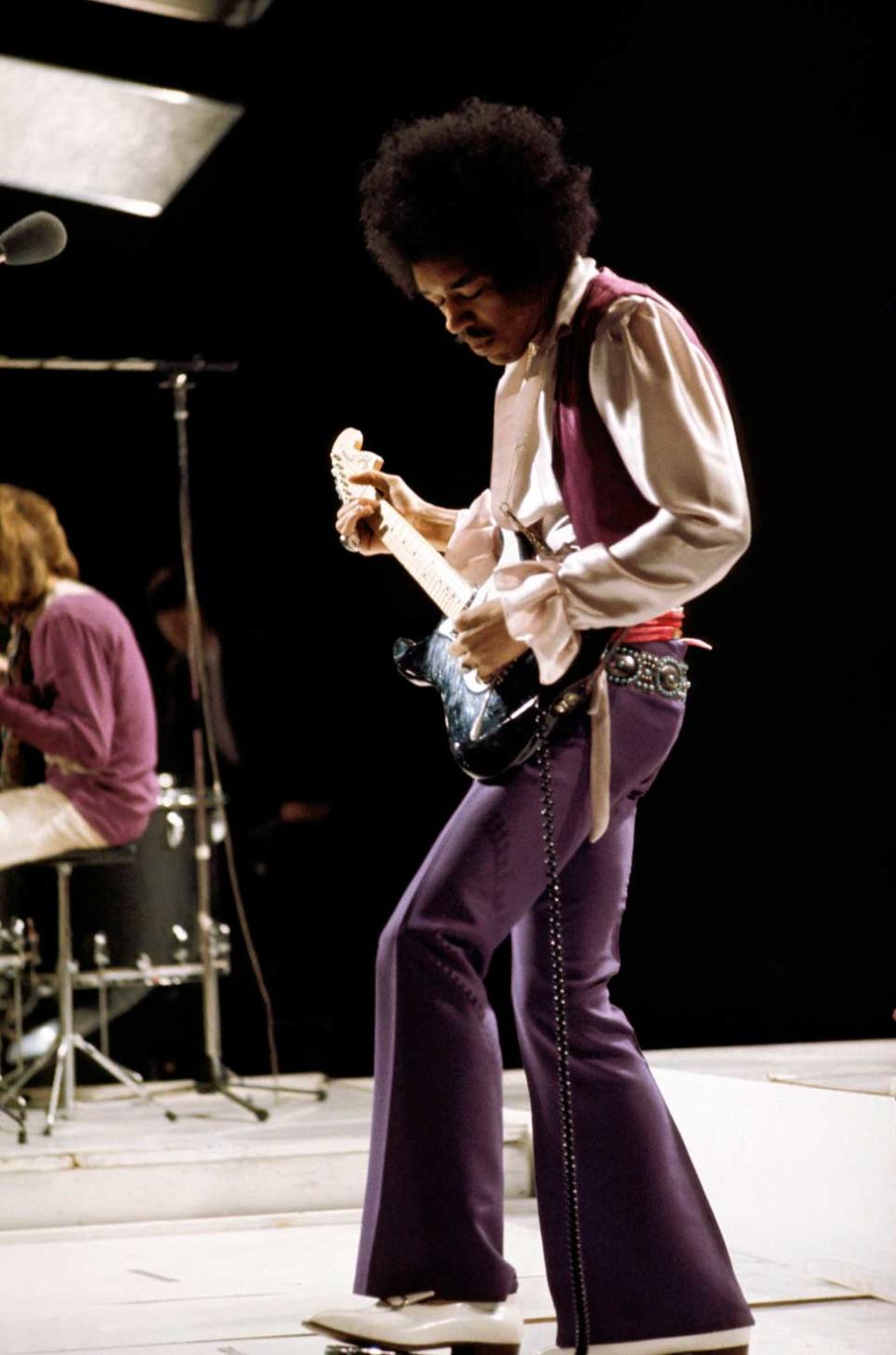

At the appointed time the band return to the studio and right on cue Hendrix, in a white shirt with puffy sleeves and flamboyant cuffs, launches into the now-legendary opening riff of Voodoo Child (Slight Return) while Mitchell sways gently on his drum-stool, getting into the groove and checking that Redding is ready too. As the song kicks in Hendrix opens up the throttle and starts ducking around in characteristic mode and by the time he starts singing his right hand is flying up and down the fretboard (he was left-handed, remember). While the sound is not the cleanest you may have heard from a rock band in a TV studio it’s never out of control and after four minutes Hendrix brings the song to a close with a quick burst of teeth playing.

The camera cuts to Lulu who is squashed next to someone on a chair in the front row of the audience. “That was really hot,” she beams as the applause dies down. “Yeah. Well, ladies and gentlemen, in case you didn’t know, Jimi and the boys won, in a big American magazine called Billboard (At this point there’s a quick squeak of feedback and she smiles towards the band), the group of the year. And they’re gonna sing for you now the song that absolutely made them in this country, and I’d love to hear them sing it, Hey Joe.”

The camera cuts back to the Experience and Hendrix mutters something inaudible to the rest of the band before counting them in to a heavy chord that is nothing like the intro to Hey Joe. The chord dissolves into waves of controlled feedback, almost as if Hendrix is going to break into The Star Spanged Banner. Instead he starts playing jumbled fragments of Hey Joe. And when he does start singing he’s singing the right words but not necessarily in the right order. He’s also trying to retune his bottom string that the feedback has sent out of tune and throwing in unaccustomed riffs like the intro to The Beatles’ Ticket To Ride.

After two and a half minutes Hendrix brings the song to an abrupt halt and says, “We’d like to stop playing this rubbish and dedicate a song to the Cream, regardless of what kind of group they may be in. We dedicate this to Eric Clapton, Ginger Baker and Jack Bruce.” He then breaks into the opening riff of Sunshine Of Your Love and is quickly joined by Redding and Mitchell (who are not unfamiliar with the song having played it on tour in America for the last couple of months) and they play an instrumental version.

Up until now the cameras have remained fairly steady but there is pandemonium in the control room as the precisely timed conclusion to the show (that may or may not have included a duet with Lulu) is now in shreds and the producer is frantically trying to figure a way out. The floor manager is making throat-slashing gestures at Hendrix to try and get him to stop which only winds him up even more. He leans into the microphone and says “We’re being put off the air” before gradually slowing down the riff and grinding to a conclusion just as the screen goes blank.

The producer apparently refused to speak to them after the show but they were later informed that they would never appear on BBC TV again. And they never did. Eighteen months later it wouldn’t matter.

Why did Hendrix do it? We will never know for sure because no one ever asked him why and he never appeared to talk to Redding or Mitchell directly about it. In fact the whole incident appeared to been forgotten by everyone (except the BBC) within a few days.

The producer’s insistence on having Hey Joe on the show may have triggered something in Hendrix that emerged almost spontaneously during the show. In October 1968 he had been to a Cream concert in Los Angeles during their Farewell tour. He was upset by their demise and the reasons for it, and that may have brought up issues within his own band and management. Chas Chandler, who had discovered and nurtured him, had quit a few months earlier, fed up with Hendrix “wasting time in the studio”, leaving Hendrix in the less sympathetic hands of Mike Jeffery who was really only interested in making money.

The Experience would break up at the end of June 1969 when Redding quit seconds before he could be fired. Mitchell was lured back for the Woodstock Festival in August but the other four members (including Billy Cox) were all new. And that band didn’t last a month afterwards.