The Haunted Life of Lisa Marie Presley

Just before 2 a.m. on the morning of Sunday, Jan. 8, David Kessler was in his room at a hotel near Graceland when he heard a knock on his door. It was his friend Lisa Marie Presley. “Let’s go out,” she said. It was time to visit her father and one of her children.

Kessler, a friend and grief specialist based in Los Angeles, had met Presley in summer 2020, shortly after the death of her son, Ben. That tragedy felt like the latest in a series of upheavals in her life, starting with the loss of her father, Elvis Presley, in 1977, when she was only nine. Since then, the woman who friends called “LMP” had endured a turbulent ride of her own: four marriages, four divorces, battles with addiction, family loss, and the airing of her train-wreck finances for the world to judge. “I’m a tabloid queen … princess … whatever you want to call me,” Presley told Rolling Stone in 2003. Some of that upheaval and angst was documented, or alluded to, on the three albums she’d made. As producer Glen Ballard, who worked on one of them, would note, “It was never an easy journey for her.”

More from Rolling Stone

That she had ventured into music at all was remarkably gutsy. It was impossible to look at her and not see her father’s smoldering sensuality and sultry gaze, along with hints of his curled lip. Her mother Priscilla’s porcelain beauty was also apparent. As she well knew, the comparisons to her dad were inevitable. Singer-songwriter Samantha Harlow beheld the expectations for herself when she opened for Presley at a show at Nashville’s Exit/In club in 2012. Stepping onstage for her set, Harlow observed a house packed with women older than her, pressed against the stage, eagerly awaiting the arrival of the daughter of the King. “She had so much weight on her shoulders,” Harlow says. “I can’t imagine what it would have been to carry the responsibility of her father’s legacy.”

But Presley — or Lisa Marie, as Elvis fans always called her — had a charisma of her own. “There’s a genuine swagger to a star,” says producer and songwriter Linda Perry, who also worked with Presley. “Keith Richards has it, Courtney Love and Harry Styles have it. They just walk a little different than other stars, and Lisa Marie was so interesting too — there was something dark about her, a mystery around her.” The mere fact that she soldiered on was inspiring. Everybody yearns to carve out a life for themselves apart from their parents, and here was someone trying to do that against absurdly overwhelming odds. If she could do it, so, maybe, could you.

Every Jan. 8, Elvis loyalists from around the globe congregate at Graceland to commemorate his birthday in 1935, complete with a cake-cutting ceremony and a proclamation of Elvis Presley Day in the city of Memphis. His daughter, who was as private as her father was provocative, rarely attended such events. This year, however, she was making an exception, but she had one thing to do first. Wearing a floral-pattern coat to ward off the middle-of-night chill, Presley beckoned Kessler into one of the golf carts she would regularly use to navigate Graceland’s 14 acres. As her friend held on, she hit the pedal and began whipping around the paved roads that snaked through the property — so fast that Kessler, who was accustomed to golf carts that puttered along, asked if there were seat belts. “No seat belts!” Kessler remembers her barking back.

“Here we are, in the middle of the night, driving around Graceland,” Kessler says. “I can’t even see in the dark where she’s going, but she can close her eyes because she knows these roads so well.”

Finally, they arrived at their destination: the Meditation Garden, the patch of ground behind Graceland that includes a circular fountain and, most prominently, the graves of Elvis, his parents, and Ben. Kessler, who sensed that Graceland was, as he puts it, her “happy place,” assumed she wanted to pay her respects to her family before the Graceland gates opened and the public swarmed in. Stepping out of the cart, they took a seat on some steps in front of Ben’s grave.

“I’ll be right there next to him someday,” she said, according to Kessler, motioning to the empty space next to where Ben had been laid to rest.

Not for a long time, Kessler replied.

“No, no — it’s going to be a long time,” she told him. “I really want to do things. I have a lot more to do.”

After silently sitting at Ben’s grave for a bit, they moved over to her father’s burial spot, directly across from Ben’s. Kessler took the conversation as an encouraging sign. The past few years had been brutal, and perhaps Presley was finally emerging from a period that, even for her family, seemed especially dark. “I’ve dealt with death, grief and loss since the age of 9 years old,” she wrote in an article for People months before. “I’ve had more than anyone’s fair share of it in my lifetime and somehow, I’ve made it this far. … It’s a real choice to keep going, one that I have to make every single day and one that is constantly challenging to say the least.”

Just over a half hour later, they returned to the golf cart and headed back out to prepare for the next day’s festivities. After more than two years of seclusion, Presley was ready to reengage with the public.

But her rebirth would be sadly short-lived: Two weeks later, she would return to the Meditation Garden, under very different circumstances.

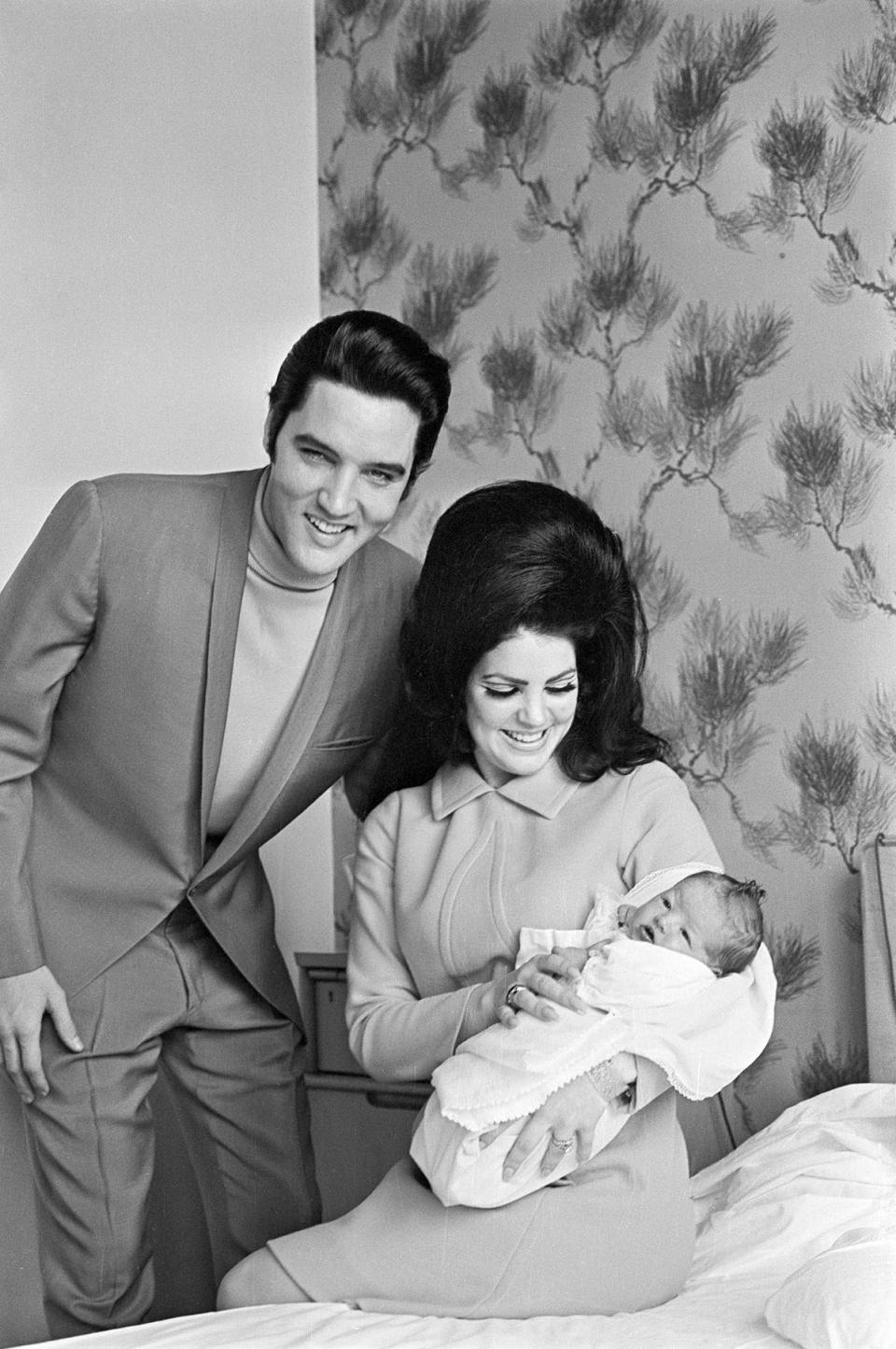

THE GOLF CARTS WERE THERE in the beginning, too. Lisa Marie Presley was born Feb. 1, 1968, and taken home from the hospital by her parents. That moment was probably the most normal of her childhood. Shortly after her fourth birthday, her parents separated, with Lisa moving with her mother to California while her dad stayed put at Graceland. When she would visit her father, for a few weeks or months at a time, Elvis was on rock-star time, generally sleeping during the day. Lisa did as she pleased, driving around the property in those carts and messing with the heads of the fans gathered outside. (She once admitted to Rolling Stone that she’d agreed to take a photo of her father for a fan, who gave her money for the task, but instead just tossed the camera.) According to Jerry Schilling, a member of her father’s close-knit posse known as the Memphis Mafia and a longtime Lisa Marie friend: “Lisa kind of ran Graceland before her dad got up. If somebody wouldn’t let her do something or the maids wouldn’t let her eat a whole chocolate cake, she’d say, ‘Well, I’m gonna tell my dad, I’m gonna fire you,’ ” he says. “But she was an adorable little girl.”

Back in L.A., Priscilla would again have to lay down the law to her rebel child. “It was really rough for Priscilla, who was a pretty strict mom — she needed to be,” Schilling says. “At Graceland, Lisa had no restrictions, basically. Priscilla had to go through the whole routine again of discipline.” When her father died in 1977, Lisa was in her room on the same floor, asking “What’s wrong with my daddy?” and trying to get into the bathroom where he lay dead, according to Elvis biographer Peter Guralnick.

It’s hard to imagine how traumatic that would have been, and Lisa Marie herself could be circumspect in talking about that day. (“I was there,” she told RS.) As she would later recall, the teenage Lisa went into what she described to Rolling Stone in 2003 as “self-destructo mode”: doing drugs (everything except heroin, crack, and mushrooms) from age 13 to 17 and, in her words, going “on a rampage.” By way of her mother, she had learned about Scientology before but reconnected with the church more fully at 17, after she’d been up for three nights on coke, as she later told Playboy. “Eventually, my mom kicked me out of the house and made me stay at the Scientology Center,” she said. “I was drinking, and she handed me over to them in the middle of the night. She wanted them to watch over me.”

As she told Schilling not long after, she wanted a job: “I think people don’t think I’m responsible,” she said. He hired her as an assistant in his management office in the late Eighties, when she was about 19. But even when she tried to lead a low-key life, she couldn’t. One day she and Schilling went to lunch — and returned to find so many paparazzi outside that they could barely get back into the building. An Elvis fan club president had leaked the news of her job. “And that ended her working for me,” Schilling says. “The word was out.”

Whether she wanted it to or not, a life in music loomed. As a child, she would sometimes hear her father sing and play gospel songs in the hallway right outside her bedroom at Graceland. She herself would sing in the bedroom mirror, using a tennis racket as her microphone; Schilling remembers her listening to LPs and picking up the needle to replay the same parts of songs over and over, as if she were analyzing the arrangement. When she was 20, she made one of her first recordings, a cover of Aretha Franklin’s “Baby I Love You” that wasn’t released at the time. Then, she met musician Danny Keough and the two married in 1988; they had two children, Danielle Riley Keough (born in 1989) and Benjamin (born 1992). She wrote one of her earliest songs then too: “Give Me Strength” was a meditation on fear of death, set to an R&B groove.

During this time, Schilling became Presley’s manager and was on the verge of completing a lucrative record deal for her with Sony — which abruptly came to an end. In Rolling Stone, Presley claimed she “freaked out” and backed out of the arrangement partly because she just had her second child. But according to Schilling, it may have also had to do with the man about to become her second husband.

In 1993, Presley met Michael Jackson during an exclusive, intimate dinner at the house of Jackson’s friend. “You and me, we could get into a lot of trouble,” he supposedly said to her. “Think about that, girl.” They grew closer, and in 1994, 20 days after divorcing Keough, she married Jackson. They wed in the Dominican Republic and honeymooned at Donald Trump’s Mar-a-Lago estate: “They spent a full week in the tower and almost never came down,” Trump told Jackson biographer Steve Knopper.

Everyone on the planet was confused or baffled by the union, but for two people who grew up young in show business, it was natural to bond, even as allegations rose up around Jackson. “I got into this whole ‘I’m going to save you’ thing,” Presley told Rolling Stone in 2003. “I thought all that stuff he was doing — philanthropy and the children thing and all this stuff — was awesome, and maybe we could save the world together.”

Around her, she said, he would drink and curse and not speak in “that high voice.” They visited at least one children’s hospital together and held hands in public. Questioned about their sex life in their notorious joint interview in 1995 with Diane Sawyer, Presley replied, “We’re together all the time … how can you fake that 24 hours a day with somebody?” But her much-documented time with the King of Pop involved awkward PDAs, especially at the 1994 MTV Music Video Awards (“not my idea — I became part of a PR machine,” she told Rolling Stone), and an increasing strain between them over having children. Later, she told Oprah Winfrey that she gave Jackson an ultimatum — her or drugs. In January 1996, she filed for divorce.

The marriage, it seems, also briefly derailed her burgeoning music career. Weeks after she married Jackson, Schilling and Jackson met in Las Vegas, and with Presley out of the room, Jackson asked Schilling, “What’s this about Lisa and recording?” As Schilling recalls, “He didn’t have that little voice. He had his business voice. He said, ‘It would be like Princess Di [who was still alive at the time] cutting an album. She doesn’t really need that.’” In what Schilling feels was likely a mutual decision on both Presley and Jackson’s part, her first major shot in the music business was put on pause. (Neither Tommy Mottola, the former head of Sony Music, nor Dave Glew, one-time head of Epic, recalls the incident, although Mottola does add, “We got some demos and I heard some songs, which were pretty good, but we didn’t release anything.”)

Presley would call the following period after her breakup with Jackson “the worst, most stressful time in my fucking life.” In the end though, it was her father, not Jackson, who helped kickstart her career. For the 20th anniversary of Elvis’ death in 1977, she came up with the idea of singing a duet with him, inspired by Natalie Cole’s posthumous duet with her own father, Nat “King” Cole. With the help of producer David Foster, who had overseen the Cole remake, she joined her father on tape in a new version of “Don’t Cry Daddy.” Initially it was just meant for that particular gathering. But the recording and video received a slew of media attention — and seemingly revived the idea of Lisa Marie as a viable recording artist.

Soon after, she was introduced to Ballard, fresh off working on Alanis Morissette’s Jagged Little Pill. At a meeting in his office, Presley struck Ballard as “slightly guarded but slightly rebellious. She was irreverent about everything. … She moved from Memphis to Hollywood when she was 10 or so, and everybody’s a star out here. To her, it was always slightly ridiculous.”

In 1998, Ballard signed her to his Java label. According to Pete Yorn, the singer-songwriter who became one of her friends during this period, Presley knew what would come next — the media scrutiny, the comparisons to her father. “She was probably apprehensive about having to go through that,” he says. “I don’t think she was comfortable in the spotlight. But at the same time, she wanted to make music, so she was like, ‘Fuck it, let’s go do what I gotta do.’ ”

As Ballard also sensed, Presley wasn’t quite sure how she wanted to sound or what she wanted to sing about. “There was a lot for her to overcome as an artist,” he says. “Her father was Elvis Presley. She was married to Michael Jackson. It was like, ‘What am I supposed to do?’ And it was like, ‘Just express yourself.’ ” With songwriters that included Ballard and Clif Magness, she began writing about celebrity culture (“To Whom It May Concern”), her children (“So Lovely”), and Keough (“Sinking In”). During his time on the project, Ballard kept pressing her to write about her family. “I finally broke her down to the point of ‘Why wouldn’t you? I do think that people would look to hear about what you felt about it. But beyond that, wouldn’t you as an artist want to express how you felt about it?’ ” he says. “After months of conversation, she was ready to spit out the truth of her background.”

As Ballard played a drop-D tuning on a guitar, Presley began singing about her father and family legacy: “Someone turned the lights out down in Memphis/That’s where my family is buried and gone/Last time I was there, I noticed a space left/Yeah, they’re down in Memphis in the damn back lawn.’” Says Ballard, “At that moment, she surrendered all of her defenses and really talked about what it was like.”

In an example of the way she often proudly refused to do as she was told, she didn’t want that song, “Lights Out,” to be the lead single from her debut album, To Whom It May Concern, which Capitol ultimately released in 2003. “I don’t think she ever wanted it to come out,” Ballard says. But the business prevailed, and, after a few false starts, Lisa Marie Presley was introduced to the world with that song. As she told RS of her debut album overall, “This is how either fucked up I am, or crazy or deranged or stupid or whatever you want to call it. This is me.”

ALANIS MORISSETTE NEEDED A BREAK, and took one in a rented house in Malibu. She was in the midst of becoming one of pop’s biggest new stars on the heels of 1995’s Jagged Little Pill. One day during her well-earned downtime, she was chilling on the back porch of her home — eating, of all things, a peanut-butter-and-banana sandwich, Elvis’ favorite — when a woman and two children approached her. “I was a little caught off-guard,” Morissette recalls. “And then she leaned in and said, ‘Hi, Alanis, it’s Lisa Marie.’ ”

Presley, with her children Riley and Ben, was in a home a few doors down. They giggled together over Morissette’s choice of sandwich, but Morissette also sensed that Presley knew what she was going through. “It was really striking to see how deeply empathetic she was toward me,” she says. “I was in the middle of the white-hot heat zeitgeist and felt pretty isolated. She could hold the complexity of what it means to be in the public eye, to navigate there. There was a quiet connection we immediately had, and I don’t have that with a lot of people.”

As she entered the L.A. music business of the mid-Nineties and into the next decade, Presley wasn’t just developing her own, non-Elvis sound but also endearing herself to the music community. She invited some of her musician friends to private tours of Graceland, even escorting Johnny Ramone and his wife, Linda, into Elvis’ bedroom. Not long after she’d met Yorn, he told her he was cutting a remake of her father’s “Suspicious Minds.” She told him she would send “the girls” — the Sweet Inspirations, the backup singers who’d toured with Elvis — to his studio to help, and much to Yorn’s surprise, they actually did show up. “Everyone loved Lisa,” says Yorn. “If she befriended you, you were stoked. She was one of the closest things you get to royalty in America. Then, when you got to know her a bit, you realized how down to earth she was. She was like a girl I would have gone to school with, but cooler.”

Another time, Presley and Yorn were backstage at one of his shows when an executive at Yorn’s label offered what Yorn felt was a mild suggestion for his music. Yorn wasn’t rattled, but Presley, sitting on the couch next to him, leapt up. “She pounced on him,” Yorn says. “She was like a mama bear protecting her cub: ‘Shut the fuck up! You don’t know what the fuck you’re talking about!’ I was like, ‘Whoa, LMP, you’re fucking awesome!’ ”

Not surprisingly for someone who was both a teen in the Eighties and also someone who knew well about death and darkness, she gravitated toward music that was hard and dark — and to the people who made it. During that period, her friends or mentors included Rob Zombie and Billy Corgan. “She was really guitar-oriented,” Ballard says. “It was usually me and my ’79 Fender Stratocaster in overdrive, playing power chords, and she was like, ‘OK, I like that.’ ” Her macabre side — perhaps the result of being confronted with a parent’s death at an early age — also emerged when she hosted one of her star-jammed birthday parties, this one aboard the Queen Mary, the luxury liner turned museum anchored in nearby Long Beach. She and her guests held a séance in the empty pool in the basement of the ship. “It was spooky,” says Yorn, who was invited. “Everyone said it was haunted. My friend was in the room next to ours, and he swears that in the middle of the night, his music system turned on out of nowhere. It was a cool memory, but I didn’t sleep a wink.”

The way she was trying to carve out her own sound — a splash of harder rock, a dab of pop-punk — was apparent in other ways. At the home of Johnny Ramone, who had relocated to Los Angeles after the breakup of the Ramones, Presley was given a tour of Ramone’s special “Elvis Room,” which included rare collectibles (like a champagne bottle from his and Priscilla’s wedding) and a jukebox filled with Fifties rock from her father, the Everly Brothers and other peers. “Johnny always wanted her to listen to stuff in the jukebox,” says Linda Ramone. “But she didn’t like it. She liked Guns N’ Roses, Marilyn Manson, and Queen.”

She and Johnny and Linda Ramone formed a particularly tight bond. In another move that evoked her father, they would fly to Las Vegas to see acts like Tom Jones or Siegfried & Roy and play the slots. Although Presley didn’t know much about the Ramones — she was more a Sex Pistols fan and only watched Rock ‘n’ Roll High School after Johnny told her about it — they became close pals. One Fourth of July, the three went to a beach and compared notes on what kind of firecracker they’d be: “Johnny says, ‘I’d be an M80,’ and she says, ‘Cherry bomb,’ ” Linda says. “They both wanted to blow up everything.” It was at Ramone’s house in 2000 that she met Nicolas Cage — who, weirdly, had come bearing a gift for Ramone: a receipt, signed by Elvis, for a gun purchase. (The two would leave their respective partners at the time, get married in summer 2002, and break up months later, finalizing their divorce in 2004.) When Ramone was dying of prostate cancer in 2004, Presley visited him in the hospital every day, gently massaging his feet. “Johnny was the most ticklish person ever,” Linda Ramone says. “He’d be so crazy at the thought of it. And what is she doing? She’s sitting there rubbing Johnny’s feet. And he’s just in heaven. That was their friendship.”

For her second album, 2005’s adult-emo Now What, Presley turned to Perry, who hadn’t met Presley before. Presley told Perry she wanted to be even more engaged with the writing on her next record and, as Perry interpreted it, wanted it to be less glossy. “She just wanted to tell her story,” Perry says. Perry would grab an instrument and play and encourage Presley to “open up your mouth and say whatever comes out.” In one of their first collaborations, “I’ll Figure It Out,” Presley referred to herself as a “boat-rocking troublemaker/Nonconforming shit starter/With the rebel DNA, the pirate spirit.” As Perry recalls, “Her dad was a rebel. And that was just her just saying, ‘Yeah, I have the DNA in me.’ ”

Dutifully promoting Now What, Presley sat for interviews with Howard Stern and Oprah Winfrey that circled back, once more, to her marriages, especially Michael Jackson. Presley handled them with aplomb and a barely contained sense of patience. In early 2006, she married her fourth husband, Michael Lockwood, a tall, lanky guitarist who had worked with Aimee Mann and others, was now in Presley’s band, and would eventually serve as her musical director. Two years later, Presley gave birth to their twin girls, Finley and Harper.

But Presley’s life and career began running into more headwinds. Now What didn’t sell as well as To Whom It May Concern, and soon after, she and Capitol parted ways. Even more troubling, she later wrote — in the introduction to the 2019 book The United States of Opioids: A Prescription for Liberating a Nation in Pain — that a doctor prescribed her opioids as a result of child-birth pain. It was, she said, a “short-term prescription,” but would soon lead to a full-blown addiction.

SHE NEEDED TO GET AWAY and did, and music again played a role in the makeover. Presley had a new manager, Simon Fuller, who had worked with the Spice Girls, and decided to meet and collaborate with British songwriters. Visiting London she hooked up with Ed Harcourt, Richard Hawley, and Travis’ Fran Healy, among others. “She definitely had a few things she wanted to say,” says Harcourt. “She had just come out of a few things that had been quite damaging.” Over the course of a few days, the two huddled over a piano and wrote songs. Presley wanted to call one of them “Shitstorm” until Harcourt pointed out that perhaps something softer, like “Storm of Nails,” would be better. Her salty language and frankness came through: “If something wasn’t great, she’d just say to you, ‘That’s shit,’ ” he laughs. “She was very honest.”

Presley was so captivated by England, especially its gray weather, that she decided to relocate. In 2010, she and her family moved to a 50-acre, roughly $9 million home in the village of Rotherfield in East Sussex, an hour and a half outside London. “I was around the wrong people for a long time, people who have no conscience, people who are doing the most draconian things and I had no idea about any of it,” she told the Daily Mail at the time. “I was an emotional wreck; therefore I needed simplicity.” She never specified whether she was referring to people in her personal life or in the music business. Around this time, she also broke with the Church of Scientology. According to Schilling, lifestyle may have factored into her leaving California as well. “She had problems growing up in L.A., and she didn’t want her kids to go through that type of environment that might be conducive to drugs or whatever,” says Schilling. “I really think that was the main motive.”

But while her farm was remote, it wasn’t always a total escape. When she was writing with Harcourt in his London studio, he glimpsed what her life was like when she arrived late for a session. “She showed up a bit flustered and a bit like, ‘Sorry I’m late. The car nearly crashed because we were trying to escape these paparazzi.’ I was like, ‘Jesus.’ It was a bit of a crazy life.”

T Bone Burnett came aboard to produce the album, Storm & Grace, which recast Presley as more of an Americana singer-songwriter. Burnett thought of her as “soulful” and admired her “beautiful, tough-minded songs,” he tells Rolling Stone. With it, fresh possibilities seemed to arise: She was on a new label, the record was her most warmly received, and questions about Jackson and Cage no longer dominated interviews. She was now two years older than her father when he died, a milestone of its own.

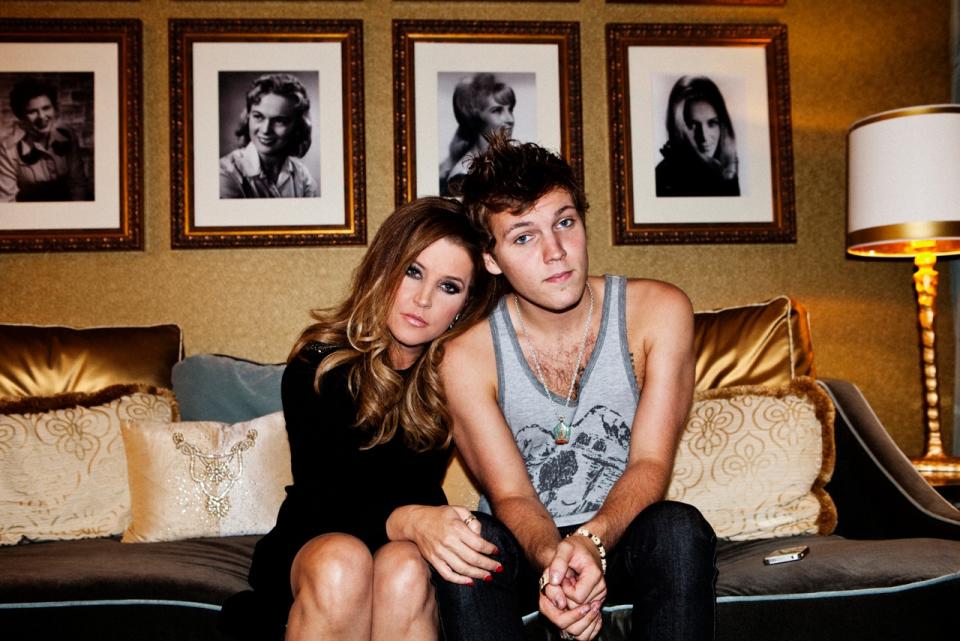

As part of the promotional push for the album, she was invited to perform, for the first time, on the Grand Ole Opry in Nashville. Arriving at the Opry House for rehearsal the day before, she quietly walked up and down each row of the empty theater, alone and lost in thought; after all, her father had performed on the Opry (and bombed) in 1954. Her family, including her young daughters and son Ben, joined her. Visitors fussed over Ben and how much he resembled his grandfather. Some of Elvis’ musicians and singers, including guitarist James Burton, enveloped Presley.

Also backstage was country singer and songwriter Larry Gatlin; Elvis had cut a few of his songs. To him, she seemed “a little bit fidgety,” and she admitted she was nervous. Of the songs he wrote for her father, Presley said her favorite was “Help Me,” with lines like, “Remove the chains of darkness/And let me see, Lord, let me see/Just where I fit into your master plan.” But in general, Presley seemed pleased with the crowd response and the backstage reception at what amounted to something of a homecoming. “Overwhelmed by the warmth,” she wrote in an Opry questionnaire she was asked to fill out before the show. (In answer to the question “Right now I could really go for,” she wrote, “a few shots of anything.”) The experience so moved her that, three years later, she’d text Opry talent director Gina Keltner, “OMG!!!! Wow. Best night of my life,” followed by seven smile emojis.

THE TEXT WOULD PROVE prophetic, since her world imploded right after. In 2016, she left Nashville, where she and her family had relocated after England, and returned to L.A. Citing “irreconcilable differences,” she filed for divorce from Lockwood. The battle, which involved custody of their two children, was personal and acrimonious. Later, she would admit that she had again lapsed into opioid addiction (the result of severe back pain, according to a source in her camp), possibly with cocaine mixed in, according to a court deposition during her divorce from Lockwood. She went into rehab in 2016, one of several such treatments. “I was not happy,” she admitted in a Today show interview. “I have a therapist and she said, ‘You are a miracle, you really are.’ She said, ‘I don’t know how you’re still alive.’ ”

But even if her addiction was put at bay, her troubles were far from over. In the midst of her personal drama, Presley became embroiled in another, even more public situation, this time involving her finances. In 1993, when she was 25, Presley was put in charge of Elvis Presley Enterprises as per her father’s will. A decade later, according to court papers, EPE was $20 million in the hole, thanks to what Provident Financial Management, the firm handling EPE finances, called “continuous, excessive spending” on her part. Presley and EPE were salvaged when, in 2005, Presley sold an 85 percent interest in EPE to CKX, the company that also owned American Idol. (However, she retained ownership of Graceland and her father’s possessions, including his clothes, cars, and musical instruments.) As Provident claimed in court documents, the deal was a financial boom for her: She wound up with $40 million after taxes.

In 2011, following the stock-market crash, CKX was sold to a private-equity firm, which soon after put the rights to the licensing of the Presley estate up for sale. For $145 million, Authentic Brands Group, a New York-based marketing firm, bought the rights to license and market Presley. Joel Weinshanker, who made his name in the collectibles and memorabilia world, took over the running of Elvis Presley Enterprises, which included overseeing Graceland. Presley retained ownership of Graceland and her father’s things, and still owned 15 percent of EPE — which paid her (or, rather the trust) $100,000 a month.

In 2016, Presley suddenly terminated her agreement with Provident. Two years later, she sued the company and co-founder Barry Siegel (who was acting as a trustee of Lisa Marie Presley’s trust) for breach of trust, negligence, and constructive fraud, alleging “reckless mismanagement,” according to court documents. In a countersuit, Provident claimed Presley owed the firm $800,000 for unpaid services, and that Presley had “resumed her spendthrift ways” after the EPE deal, “spending tens of millions of dollars.” (In a court filing, she alleged she had been kept in the dark about its investments, had less than $20,000 to her name, and, thanks to Provident, had an unpaid tax bill of $10 million from 2012 to 2017.)

According to court documents, Presley claimed she was in hock for $16 million; her monthly expenses, including mortgage, credit card bills, and food, amounted to over $120,000. “Was she perfect with money?” says Weinshanker, managing partner of EPE. “Very few people are. But was she burning $100 bills to keep warm? She wasn’t doing that.” (Presley and Provident reportedly reached an out-of-court settlement.)

Amidst multi-fronted turmoil, she returned to music one more time — and again with her father, echoing the way she had first made a splash in the music business. For a new, reconfigured collection of Elvis’ gospel recordings, she agreed to record duets with him, including “Where No One Stands Alone.” No sooner had she arrived at the L.A. studio — the same one where her father had cut some of the prerecorded songs for his 1968 “comeback special” — than her stubborn-rebel side kicked in. “She goes, ‘Play me that song one more time,’ ” recalls Weinshanker, who was co-producing the project. “After, she just said, ‘Next.’ That’s Lisa. She has her opinions. It took me a little bit of time to convince her that it was the right song.”

Once Presley settled down to begin the recording process, producer Andy Childs noticed one revealing moment. As she was about to deliver one line — “Take my hand, let me stand, where no one stands alone” — Childs saw something hit her. “I’m on the other side of the glass, looking at Lisa while she’s singing, and she looked up and just kind of shook her head,” Childs says. “She had to stop and regain her composure.”

Presley resumed, but Childs read something into that moment. “Lisa had difficulties in her own life, and this is a moment where she’s singing a gospel song, with her father, about not having to stand alone,” he says. “Maybe at that moment, she felt a connection to her father.” They wound up taping another duet, “You’ll Never Walk Alone,” but ultimately decided it should remain a solo Elvis performance. They would be her last professional recordings.

AS EARLY AS AT LEAST 2014, director Baz Luhrmann had begun exploring the idea of a biopic on Presley’s father. Five years later, with the casting of Tom Hanks as Elvis’ polarizing manager, Colonel Tom Parker, the project began picking up steam. Going back to the days when someone had suggested she don a white jumpsuit like her father, or even cover his songs, she had learned to be wary of manipulation. “She knew exploitation,” says Morissette. “She knew being taken advantage of.”

Still, she gave signs that she was open to the idea of the film. When Luhrmann made his first visit to Graceland, Presley, home in L.A., gave her approval for him to quickly dash into her father’s bedroom, provided he didn’t take photos. She worried about how her father would be depicted in the film, but Weinshanker worked at hearing out her misgivings. “Her getting comfortable with the movie was about me reassuring her how they were going to listen, how her dad was going to be portrayed and how he’s going to be protected, because that was always important,” he says. Her rule, she told him, was to “tell the truth” about her father. “He wasn’t a perfect human being — no one is,” he remembers her saying. “Just tell the truth, give him a fair shot.”

Her oldest child, Riley, was emerging as a rising Hollywood star (she’s currently seen in Amazon’s Daisy Jones & The Six), but Riley’s brother was increasingly troubled. Just months into the filming of Elvis, in July 2020, Ben was found dead in her family’s Mediterranean-style, five-bedroom house in Calabasas. The death was ruled a suicide, and cocaine and alcohol were found in his system. Like his mother, he had been in rehab at least once, and he also dealt with depression issues, according to the L.A. Medical Examiner report. “Every parent who has a child wonders if they could have done more, and she probably felt that way,” Kessler says. “She was just a shattered person.” Soon after, she sold the house and moved to another in the same city.

Talking with Rolling Stone in 2003, Presley had joked about her career, “My guess is that I’ll do this for a while and then turn into a recluse again at some point.” That time came after her son’s death. Weeks after his passing, she was put in touch with Kessler — but insisted on grieving on her own terms. “She didn’t want someone who’d studied grief academically and would tell her what she should be doing,” he says. “She said, ‘I don’t want a therapist, I don’t need a grief counselor. If you want to be friends, I’m open to that.’ ” With his help, she began attending online sessions with other bereaved parents, who mostly didn’t recognize her, and eventually hosted some in her home. Besides her son, other family members would sometimes come up. “She might mention her father,” Kessler says. “She certainly shared, ‘the movie about my dad is coming out.’ ”

In 2019, Presley had signed a deal — reported to be between $3 million and $4 million — to write her first memoir, in which she would go even deeper into her relationship with Jackson than she had in interviews. But following Ben’s death, along with her ongoing divorce negotiations, the project fell by the wayside, and she began instead talking about writing a book about grief and becoming a grief educator herself. “I already battle with and beat myself up tirelessly and chronically, blaming myself every single day and that’s hard enough to now live with,” she wrote in 2022, “but others will judge and blame you too, even secretly or behind your back which is even more cruel and painful on top of everything else … Nothing, absolutely nothing takes away the pain, but finding support can sometimes help you feel a little bit less alone.” With palpable bitterness, she added, “Your old ‘friends’ and even your family can and will run for the hills.” She also brought up the idea of her and Kessler working on a podcast devoted to grief.

As it had in the past, she considered a return to music as a way to express herself in ways she rarely revealed in public. In late 2021 or early 2022, Perry, who hadn’t worked with her since Now What, reached out again. “Things got rough with her son passing,” says Perry. “Obviously, that was difficult. I just kept texting her saying, ‘You got to come back in the studio.’ ” They met once to discuss what could have been Presley’s first album in a decade, then reconnected in the summer. Perry says that Presley told her she was swamped but would get back to her.

The release of Luhrmann’s Elvis last summer would prove to be less traumatizing than everyone around her feared. Steeling herself, Presley watched the finished film at a private screening, where she finally gave it her OK. “She was blown the F away,” Weinshanker recalls, and says Austin Butler’s performance especially moved her: “On some level, she saw her father in him.” She hosted a screening in Los Angeles for the movie, which Linda Ramone attended. “I said to Riley, ‘Wow, it’s so intense — how does she sit through it?’ ” Ramone recalls. “She goes, ‘Go ask her,’ so I go, ‘LMP, how do you sit through it?’ She said, ‘I do. Because I loved it.’ ”

Last October, she and Lockwood finally reached a settlement agreement on their divorce, which included joint custody of their two children. As much as she seemed to be clearing the decks, though, those around her sensed the impact the previous few years had taken on her. A few months before the divorce settlement, she and Schilling flew to Memphis for an advanced screening of Elvis. Schilling thinks he hadn’t seen her since Ben’s funeral, two years before. “At the airport, she said to me, ‘I’m not the same and I never will be,’ ” Schilling says. “You could see the stress she’d been through. But she was trying her best.”

Around the start of 2023, Perry reminded herself to prod Presley once more. “There was an urgency to me,” she says. “I wanted her in the studio because I knew she needed to get in here and start recording, and she knew that needed to happen as well. Music is just so healing.”

STARTING WITH HER LATE-NIGHT RIDE at Graceland, the last week of Presley’s life was, much like her life itself, a combination of past, present, and an elusive future. On the night of Thursday, Jan. 5, she had flown to Memphis by herself, on a commercial flight. Late that Saturday night into Sunday morning, she visited Elvis’ and Ben’s graves with Kessler. She likely only had a few hours’ sleep before she had to prepare for her father’s birthday celebration.

It had rained in Memphis the night before, making the ground wet, muddy, and inappropriate for the high heels she decided to wear. “That’s going to be the headline: Lisa Marie Presley falling in the mud on the way to her dad’s birthday party,” she cracked to Kessler as they walked toward a tent with Elvis’ cake. Dressed in black, her eyes hidden behind sunglasses, she held onto Weinshanker’s arm as she approached a podium to address the faithful gathered. “I keep saying you’re the only people that can bring me out of my house,” she half-joked. “I’m not kidding.” After she signed autographs and posed for selfies with a long line of Elvis fans, she took a flight back to Los Angeles later that afternoon on Weinshanker’s private plane. That same night, another Elvis-related event was on schedule: a birthday party for him at the Formosa Cafe in West Hollywood, one of her father’s old haunts.

Luhrmann, Butler, and her daughter Riley were there, and Presley briefly addressed the gathering, saying she was “so proud” of the film, “and I know that my father would also be very proud.” Twice she used the word “overwhelmed.” There, she asked Schilling if he would accompany her two nights later on the red carpet at the Golden Globes, where Elvis was up for several awards. She told Schilling she would be coming alone, so he should keep an eye out for her.

Dressed again in black, as she was at the Formosa gathering, Presley arrived at the Beverly Hilton early that evening. When she saw the footage of Presley at the event, Linda Ramone was encouraged: “I was just thinking, ‘Oh, wow, this is great — she’s going out again.’ She hadn’t gone out for a long time after Ben.” What the public (including those who reached out to Ramone after) saw was a woman who looked startlingly pale and seemed to have trouble walking, clinging to Schilling, especially when she paused to give a quick interview on the red carpet.

Schilling attributes her careful steps to her footwear. As soon as she arrived, he says, “She had these huge high heels and said, ‘Oh, man, I think I’ve made a mistake with these shoes. I’m going to hold on to you, because these shoes are killer.’ ” Schilling insists the evening was “really uneventful,” adding, “Lisa was as lucid as anybody there. Anybody who says different doesn’t know what they’re talking about.” After the Globes, Presley attended a Luhrmann-thrown bash at the Chateau Marmont, staying until about midnight.

On Wednesday, Jan. 11, Presley texted her stylist, along with her manager and representative, Roger Widynowski, about which designer would handle her Oscar-ceremony dress. Thanks to the success of Elvis and the relaunching of Graceland and the Elvis brand, she appeared to be financially more secure. But loss was never far removed: Linda Ramone reached out to Presley, telling her Jeff Beck — who’d met Presley during her time in England — had died the day before. Ramone texted Presley a photo of her, Presley, and Beck together, and Presley wrote back, “Oh my God, I can’t believe he died.”

The next day, Jan. 12, paramedics rushed to a rented home in Calabasas, complete with a view of the mountains, to attend to a woman in “full cardiac arrest.” A housekeeper had found Presley in her bedroom. Danny Keough, who remained close to his ex-wife, even serving as best man to her wedding to Lockwood, had moved into the house to help her after the death of their son, Ben. He administered CPR, as did the paramedics, who initially detected signs of life. Presley was taken to West Hills Hospital, where she again went into cardiac arrest and was pronounced dead hours later. She was 54.

Presley’s cause of death remains unknown. Five days after her passing, the Los Angeles County Coroner announced that the investigation was deferred and that the medical examiner was requesting further information, “including additional studies.” That inquiry is still underway. A number of factors can increase the risk of cardiac arrest, from family history and health issues to drug use. Her father died from cardiac arrest (his mother, Gladys, died from heart failure), and Presley had admitted to substance abuse in the past. (According to Kessler, she had also complained about stomach pain in the weeks before her death.) TMZ reported that she had slipped back into opioid use, but Presley’s camp denies those reports. One thing is clear, though: Despite carving out a life and career of her own, she was repeatedly pulled back into the same types of personal, financial, and health turmoil that had engulfed her father, and fought to overcome them to the end.

On Jan. 22, exactly two weeks after her early-morning visit to the Meditation Garden, Presley was laid to rest next to her son. On a slate-gray morning, thousands of mourners gathered outside the gates of Graceland; musician friends like Corgan, Morissette and Axl Rose played songs in her honor. After the service, family and friends walked to the garden and her grave. Ballard, one of the attendees, couldn’t help but think of the lyrics she’d written for “Lights Out” two decades before. “She’s talking about being buried in the damn back lawn,” he recalled a few days later. “And I just walked past that damn back lawn yesterday. Not only was I was chilled by the cold, but just like the whole irony of it all and the prophetic nature of it. It will always be with me.”

On the same day as her service, on the other side of the Atlantic, Ed Harcourt’s son grabbed a comic book in their London home. Harcourt sometimes would stash work papers in books, and in this case, out fell a handwritten lyric to a song he and Presley had written together but hadn’t included on Storm & Grace. It was called “Light of Day,” and in perfectly handwritten prose with no cross-outs, it read, in part, “There’s a gift that you’ve been given/There’s a role you need to play/There’s a light to be taken/Now let it be the light of day.”

Best of Rolling Stone