“You hear bombs, a baby being born, an eagle flying, you hear things that people don’t normally hear”: how Jimi Hendrix pulled back from the brink of disaster at Woodstock and sealed his legend

If ever an event has grown in the telling, it was Jimi Hendrix’s performance at Woodstock in August 1969. Mismanaged on a cosmic – if not comic – scale, the performance has subsequently morphed into one of the most iconic moments in the history of rock.

Arguably the biggest name and reportedly the highest paid performer on the three-day bill, Hendrix was supposed to bring the festival to a triumphant close at midnight on the final Sunday, August 17. But this was the 1960s, and “technical and weather” delays meant that Hendrix eventually took to the stage at 8.30am the following morning. The massive crowd – estimated at half-a-million at its peak - had dwindled to a mere 40,000, many of whom had only hung around to get a sight of Hendrix, before making a hurried exit as the start of the week beckoned.

Thrust on stage in the cold light of day, Hendrix was faced with every performer’s worst nightmare – an audience drifting inexorably towards the exits before his eyes. “You can leave if you want to, we’re just jamming, that’s all,” he said disconsolately towards the end of the show, as the band meandered somewhat aimlessly through Stepping Stone, an unfamiliar song to audience and musicians alike.

Although introduced by the MC as the Jimi Hendrix Experience, Hendrix was not, in fact, leading the Experience, but road-testing a new group which he had put together only a few weeks before. This was their very first gig. “We decided to change the whole thing around and call it Gypsy, Sun And Rainbows,” Hendrix explained, as he took the stage. Alongside drummer Mitch Mitchell and bassist Billy Cox, the line-up also included guitarist and singer Larry Lee, and percussionists Juma Sultan and Jerry Velez.

The six-piece band had barely rehearsed and Mitchell later remarked that it was the only group he had ever played with that did not get better with practice. “The band was grim,” he declared.

“Jimi’s intentions were good,” Cox added. “But it just didn’t work when you had congas and timbales competing with what Mitch was trying to play.” The engineers who mixed the live sound, and the camera operators filming the show seemed to agree, and everyone involved evidently came to an unspoken agreement to treat Lee and the two additional percussionists as if they simply weren’t there.

The lack of rehearsal, loss of sleep and steady haemorrhaging of the audience throughout the performance was compounded by Hendrix’s decision to include in a long setlist a bunch of as-yet-unreleased songs which were either unfamiliar (Message To Love, Hear My Train A Coming, Izabella), unfinished (the rather impressive Jam Back At The House), or completely off the radar (Master Mind and Gypsy Woman/Aware Of Love, two numbers featuring Lee on lead vocals, the success of which may be judged by the fact that neither of them has seen the light of day on any Hendrix album or film footage ever released). Although he had never been inclined to exercise caution in his affairs or his music, Hendrix had truly gone off the deep end on this occasion. What was he thinking?

Spanish Castle Magic incorporated a spirited, percussion-led jam, but the ensuing Red House was one of several numbers dogged by tuning issues. This was, of course, long before electronic tuning devices had been invented and Hendrix always gave his strings a fearful bending and hammering. The fact that he was not used to playing with another six-string guitarist was an added complication on this occasion.

Two things changed the course of a gig that was heading for disaster. Firstly, although the audience had largely left, the film crew stayed put, enabling the makers of the subsequent documentary Woodstock, directed by Michael Wadleigh and edited by Martin Scorsese (among others), to include a brilliantly edited segment of Hendrix’s performance as the final sequence of the film. And secondly, Hendrix, perhaps sensing something in the zeitgeist in a way that the most gifted artists are somehow able to do, started to play his dramatically retooled version of the US national anthem.

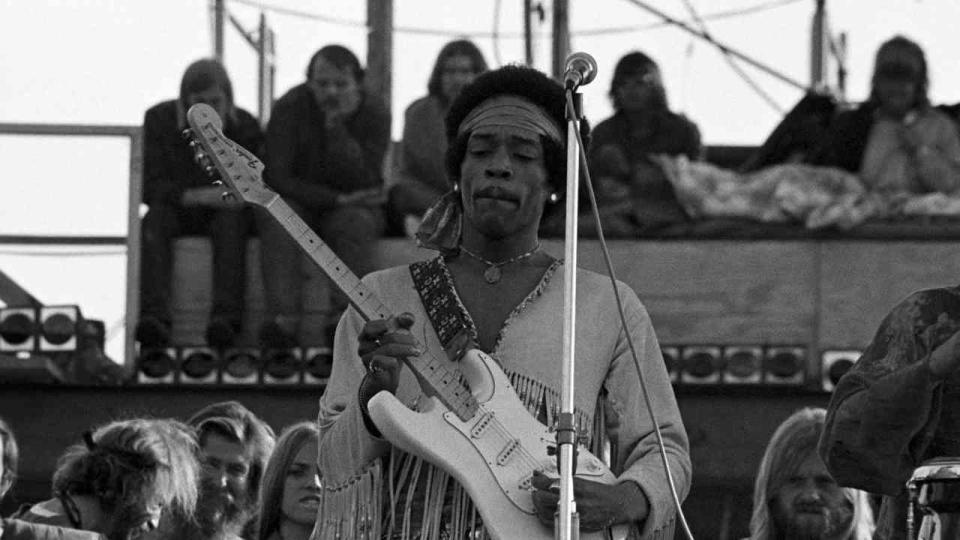

A psychedelic adaptation of The Star Spangled Banner had been a feature of his live shows for a while. But the timing and placement of this particular performance gave it a dramatic resonance that lasted long after the final, feedback-drenched notes had echoed round the fields of Bethel in upstate New York. Captured in close-up in the movie, resplendent in a white, beaded jacket and orange headband, Hendrix applied his freakishly long fingers and thumbs to wrench, bend and blast a free-form avalanche of sounds out of his white Stratocaster that conjured images of wonder, terror, anguish and awe. The rest of the band fell silent, apart from Mitchell who added a series of skittish, clattering, madcap, martial drumming sorties to the mayhem.

The familiar sequence of notes - internalised by generations of Americans as a musical representation of their national identity – were stretched and scrunched into all sorts of weird, incongruent shapes, while being all but overwhelmed by an intervening cacophony of wails, shrieks, siren-howls and juddering engine noises. Hammering his elbow against the body of the guitar while stretching his hand along the length of the tremolo bar and plunging it in to the guts of the scratchboard with a violent, jolting vibrato, Hendrix wielded an unearthly command of the electronics and physical dynamics of his upside-down instrument, throwing himself theatrically into the performance, while moving purposefully from one foot pedal to another.

Carlos Santana, another of the standout performers at the festival, was one of many who paid tribute to Hendrix’s astonishing version. “When I heard Hendrix playing at Woodstock, you hear bombs, you hear a baby being born, an eagle flying, clouds moving, you hear things that people don’t normally hear,” he said.

Coming at the end of the most significant event ever mounted by the mavens of the 1960s counter-culture, the symbolism of this rendition became magnified into something of immense and lasting importance, with commentators retrospectively ascribing all sorts of meanings to it over the years since Hendrix performed it. America at that time was embroiled in culture wars, race riots and student protests all swirling around the nexus of the Vietnam War. Hendrix’s twisted, tortured reinvention of the country’s national anthem was taken to be an alternative call to arms, a scathing rebuke and a most eloquent protest at what America had become.

Curiously however, Hendrix – who, as an ex-paratrooper with the 101st Airborne Division of the US Military had been a lot closer to the sounds and machinery of warfare than most of his cheerleaders had ever been - was never known to speak of his arrangement of the song in this way.

“We’re all Americans,” he said at a press conference a few weeks later. “It was like ‘Go America!’ We play it the way the air is in America today. The air is slightly static, see.” When asked to explain himself on a US TV show, Hendrix said, “I’m an American so I played it. They made me sing it in school, so it was a flashback. It’s not unorthodox. I thought it was beautiful.”

The legend of Hendrix’s performance that day was further cemented by another instrumental passage, a slow, melancholy blues jam known as Villanova Junction with which he counter-intuitively ended his set, and which ended the movie. On stage, Hendrix was calling out the chords and changes to the band, as he felt his way through the sequence. Meanwhile, on screen, the camera roamed across scenes of unimaginable squalor which unfolded as fans cleared up and trudged, some barefoot, through the mud and debris in the immediate aftermath of the festival.

As a soundtrack accompanying these images of dirt and decay, Hendrix’s music conjured an unbelievably poignant range of comedown emotions: sadness, serenity, peace, love, elation and desolation. A downbeat ending to an otherwise gung-ho, life-changing event, the Villanova Junction sequence in the Woodstock movie stands to this day as a perfect, fin de siecle evocation of the end of the hippie age, conveyed through music and images with a tawdry yet soulful grace.

Hendrix returned for an encore of Hey Joe, after which he left the stage, utterly exhausted. He had not slept for three days and collapsed on the steps coming down from the stage.

Woodstock changed the lives and career trajectories of just about every act that appeared at the festival, and certainly those that were featured in the ensuing film. Released in the US in March 1970, the Woodstock movie, became a phenomenon in its own right. Film footage of live music of this kind was not available for public consumption anywhere on the planet at this time, and if you wanted to see anything like it, you had to go to the cinema and see this movie. And people did. In America, on a limited distribution, Woodstock became the fifth-highest grossing movie of 1970.

Hendrix and Woodstock are inextricably linked in the mythology of the 1960s, particularly so in the UK, where the movie did not surface until June 1970. Three months after that, following another uneven performance with Mitchell and Cox at the Isle of Wight Festival, Hendrix died in London, and the end of an era was truly at hand.