HIP HOP IS DOPE, AND AMERICA IS A DOPEFIEND HOOKED ON THE FRUIT OF ITS OWN BRUTALITY

I’m driving with Truth, a friend who is a music producer. We both make rap music, but he makes beats, too. I’m an undergraduate at the small, private university in my hometown, Decatur, Illinois. He finished his undergraduate degree a couple years ago. We are leaving Jay’s house — he’s another friend — driving from his West Side neighborhood toward the campus at its edge.

It’s remarkable, while driving through this neighborhood, what distinguishes the town from university grounds. It’s not the manicured hedges and lawns. They aren’t greener, neater, or more meticulously trimmed on one side or the other. It’s the wrought iron fencing that separates them. The gates are a portal between worlds.

More from Spin:

In the short time after I glance at my rearview mirror and see the outline of the lights atop the police car that starts trailing us, my imagination takes over. My hands start sweating as I try to maintain composure. As far I can tell, Truth is unaware of our impending doom, while I am terrified that the drive will soon end with those lights swirling their red, white, and blue warning, commanding us to pull over to the shoulder. I see it happening clearly, in slow motion — the cops searching the car, opening the trunk, digging into my bookbag; us offering inadequate denials. Denials unable to protect time: to keep the time that will now be taken from us and to hold onto the time we will be taken from the world, our families, our lives. There’s no question we will be found guilty, even though we didn’t own what was in our possession.

But that scenario never happens.

The slow, silent pursuit ends when I pull up to the lacquered black gate that separates the neighborhood from university housing and swipe my I.D. The gate creaks as it slowly swings open, and we drive through to a parking spot, uninterrupted. The squad car turns right and heads back through town.

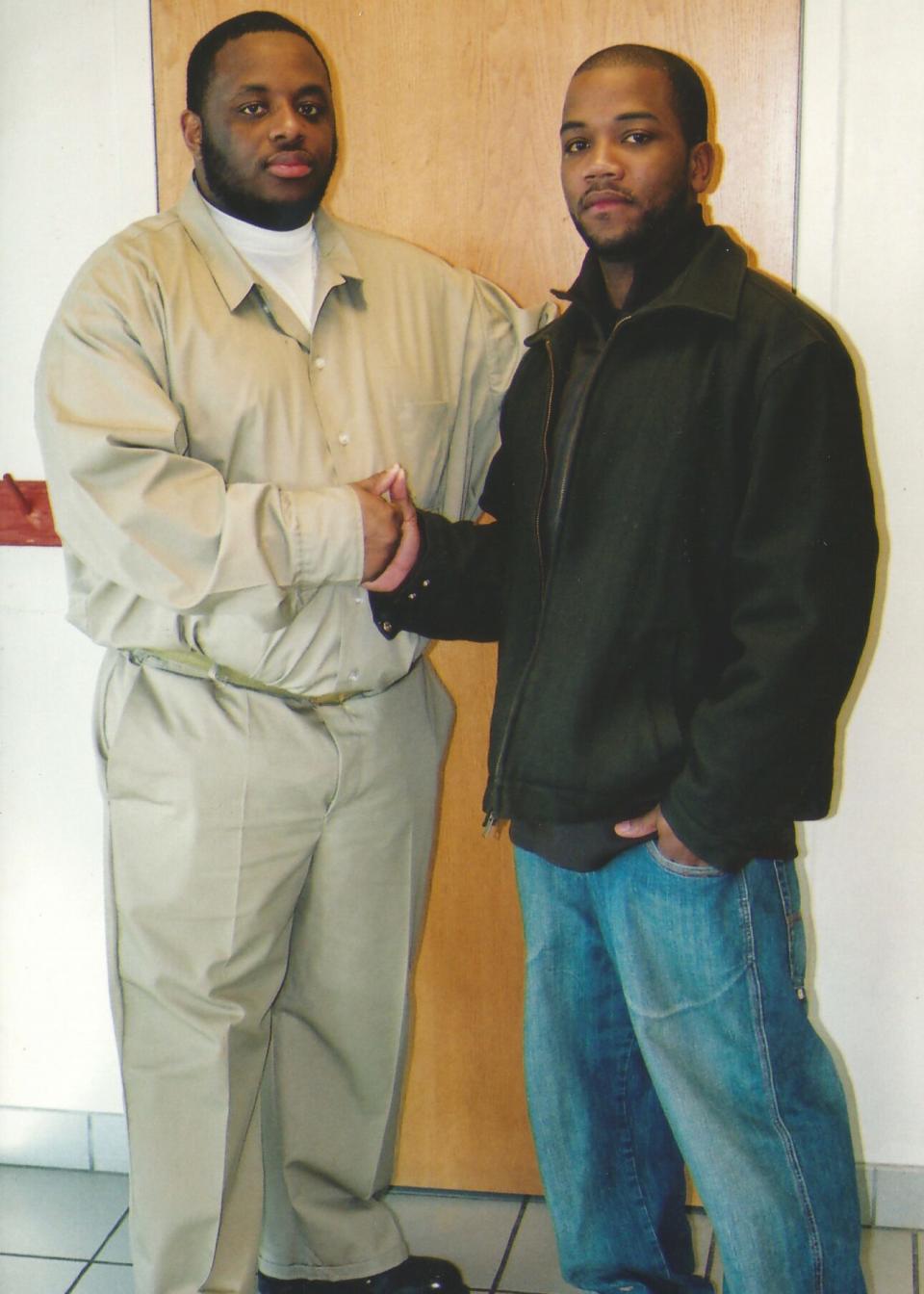

Several years later, Jay has spent roughly the same amount of time in prison as I did in graduate school. The contents of the bookbag in my trunk had changed from undergrad to postgraduate studies, but its contents on that day back in Illinois when Truth and I were headed to campus conscribed Jay to time living behind a different set of gates.

It wasn’t until I started my career as a professor at the University of Virginia that I discovered that the classroom furniture here is made by prison inmates, woefully underpaid for their labor. Jay is currently housed in a different state. Where he lives, the prisoners are paid very little to make shirts and towels for the U.S. Army.

The celebration of hip hop’s 50th year coincides with my promotion with tenure to Associate Professor of Hip Hop. It’s a momentous occasion, culturally and for my own personal, professional journey. It’s also a moment of fraught reflection. The broader cultural implications might be better understood through the personal.

On the one side is Jay, a prison inmate in a country obsessed with carceral control of Black bodies, and on the other side is me, a rapper and professor teaching through and about hip hop at a university that enslaved people built, which directly benefits from the country’s obsession with carceral control of Black bodies and whatever other ways it might be able to constrain and exploit Black people. In the middle is a thread that divides licit from illicit, legal from illegal, what’s sanctioned and what’s not. This thread is infinitesimally thin, and what exists on either side are gears working together to power the same machine. The machine is the United States.

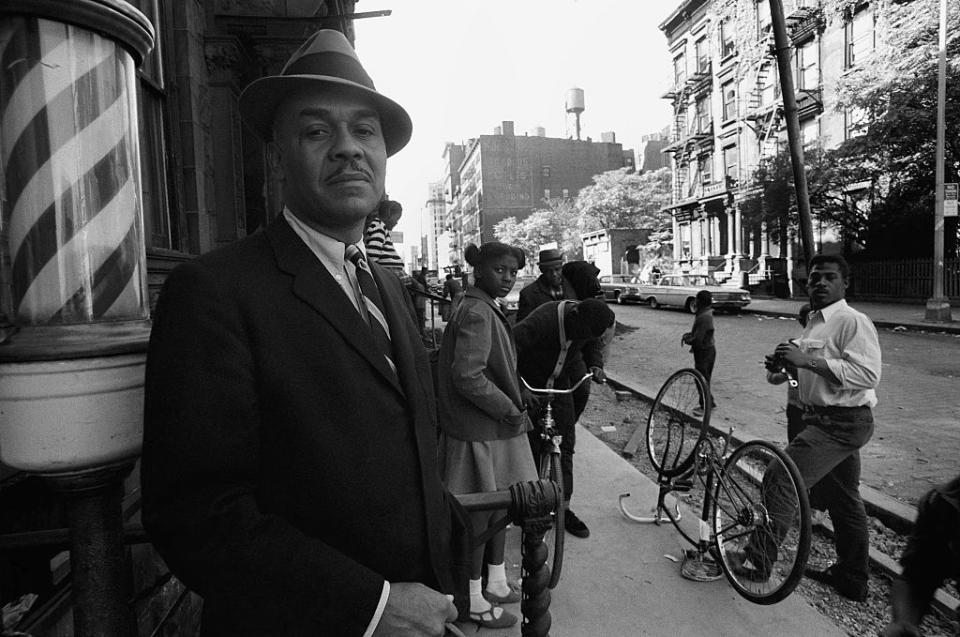

To the left is a 1912 New York Times article reporting that Johnson led a syndicate of “wealthy negroes” that planned an “invasion of the fashionable resorts of the white race”.

The churning of this machine and the realities that straddle that nearly invisible dividing line come to mind when thinking of this half-century commemoration of hip hop.

In my work, I teach people to rhyme words, how to lyrically design arguments, to decipher layered meanings in music — whether or not they’re intended by the artist. I think of history as rhyming rather than repeating. It seems a more comfortable metaphor.

The narrator of Ralph Ellison’s 1952 novel Invisible Man describes history as doing a kind of boomeranging to which we should be alert, presumably to avoid being struck across the head. He recounts an experience he has as trying to hear around corners. He talks about how he sees and feels time fall apart while under the influence of drugs people have given him. Under the influence of dope, he comes into a different way of listening. He also is, somehow, able to commune with ancestors and people who are not in the underground room in which he’s hiding. Through these experiences, he learns about himself and the world around.

Dope is how I think about my work teaching, writing, rhyming, composing, listening, and being.

Us — the U.S. — and drugs, are fused in our storytelling. Drugs are in our literature. They’re a primary obstacle and escape for the protagonists in any number of acclaimed films. Our music across genres is steeped in drugs. Our modes of entertainment are informed by the realities of drug use. These, too – the fictions and their factual counterparts – fuel the same machine: America.

We can look through the past 50 years of hip hop and see Black people, Black art, and Blackness itself used, taken, ingested as a kind of dope that has both resisted and powered the machine, flowing side to side across America’s il/licit line.

Philosopher Avital Ronell, author of Crack Wars, describes intoxication as a method of “making phantoms appear.” And it’s more than that, she says; it’s a way of “treating the phantom, either by making it emerge — or vanish.”

Dope. It makes talking to ghosts possible.

The symbiotic relationship between me and hip hop is analogous to dope. I take it, and it takes me. As in Ronell’s narco-shamanism, hip hop transports me into longform discussions with disembodied voices, breaths breathed into instruments, sequences punched into machines that have preserved music made by people passed on. It feels like conjuring: like magic.

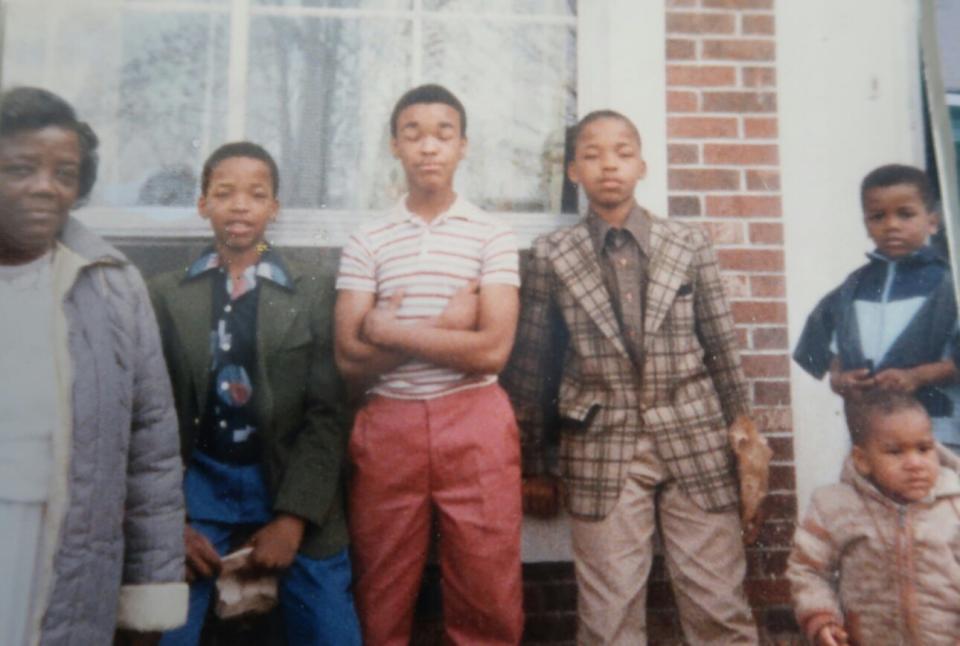

To mark this 50th commemoration of hip hop I’ve recorded an album I call a mixtap/e/ssay on which I converse with ghosts. On V:ILLICIT, the ghosts I’m talking with are family members like my grandmothers, Alice and Emma, my cousin Devin Slater, who was killed in 2020. I’m also talking to the day laborer named Samuel J. Bush and the racist white mob that lynched him in my hometown of Decatur, Illinois, in the summer of 1893. The voices of Toni Morrison, James Baldwin (in conversation with Nikki Giovanni), Fannie Lou Hamer, and the Senegalese film artist Sembène Ousmane are in the mix as well.

This work isn’t only commemorative. I’ve spent my entire academic life talking to ghosts and thinking about drugs: how drugs affected me and my loved ones. And I’ve been listening.

All those years ago, I was just holding that bookbag as a favor for Jay. I never knew the exact contents or quantities. In a way, we thought we were being made into something like the bag’s contents. After all, those university gates were meant to keep people like us — and the contents of our bookbags — out. It’s not hard to understand how we, too, were perceived as illicit. Perhaps we could also be dope.

And we turned what was in that bag — that weight of potential that Ellison’s narrator, a man forced mystic by the power of unrelenting alienation — into beats and rhymes. We are part of a legacy of building with what other people assume is broken and often try to break if it isn’t already.

Scribbling verses for my assignments and rapping my coursework, I traded those beats and rhymes for academic credits toward degrees that eventually made my reality reflect my dreams. I stayed inside those wrought iron gates until I earned a Ph.D. Now I teach behind similar gates. Back then, our dopeness — who we were, who we wanted to be — was aspirational, what we might make with what we were given, or how we might make do despite what we didn’t have. It was what history repeatedly calls the American Dream.

For me and my friends, the university gates were a short-term barricade. It might be where police turn right and focus their attention on other potential crimes and criminals, but it could never remove the presumed criminality from our Black bodies, even if we were accepted into their classrooms and worked our way through their curricula.

Dope was the reason that, at the culmination of my career as a student, I wrote a rap album for my doctoral dissertation. I’m here now because I don’t belong. This feels like a fitting way to think about hip hop in America after 50 years.

Hip hop provided the alternative curriculum that we worked through outside the university gates but which served us just as well on campus. The illicit conjurings I scribbled back then before I became a Doctor, rhymes pressed into the pages of composition notebooks, napkins, and the empty faces of envelopes, are now prescriptions in rap form. And they don’t only prescribe. They’re scripts about things as I see them unfolding now. Sometimes, they’re postscripts, detailing stories of the past.

But, still, they are dope, which isn’t just a particular substance. Dope is as much about how the substance comes into being, the circumstances that make the substance possible. It’s also about context. Whatever gets prescribed and picked up from a pharmacy isn’t dope, even if it is drugs. That it’s sanctioned, allowed, part of an over-the-counter economy, changes the contours and character of its dopeness, and maybe even the quality. The exact same substance sold out the side door would change the relationship of the substance to its sanctioning. Illicitness has potency. More: illicitness is potency. And maybe what I’m saying is drugs vs. dope depends on the door – or the gate.

As an academic, I sometimes meet people who call rappers like me poets when they are describing what they think I do for a living. They do this, I think, to try to convince people who respect poetry to respect rap, too. They believe they can use poetry to smuggle rap across that razor-thin, almost imperceptible line that separates what’s acceptable and what’s not. Poetry is offered as cover so a rapper might walk through the gates of respectability unmolested. The attempt to make the illicit legal against its own definition, by redefining it in more acceptable terms, is narrative violence.

If they said I was “like a poet,” using a simile instead of the metaphor, I’d feel more comfortable with it. But they don’t. I’m attentive to figurative language. It’s of great use to rappers like me, especially after five decades of hip hop.

Numerous American institutions erected wrought iron gates to exclude hip hop and the people who make it over these past 50 years. I imagine many of these places will seem a lot like pharmacies trying to convince the world that dope has been decriminalized and they are now celebrating a half-century of its salvific benefits. They might advertise it over the counter or out the side door.

I can’t trust anyone trying to sell me the sanctioned version of what I am while denying the discomfort and unease of what created the real me. I’d more readily believe the people who are still here and repeat their disagreement with hollow celebrations of our resilience, and the ghosts with whom we have ongoing conversations, long before I’d believe anybody it took 50 years to convince.

If it qualifies as a metaphor, I imagine this is a comfortable one for America. Despite what has been made these past 50 years, against all odds, it would be entirely too uncomfortable for me to say, “hip hop is like America.” I suspect that’s probably mutual.

But I feel completely comfortable saying I am hip hop, hip hop is dope, and being Black while being dope is equal parts dream and nightmare when the same folks addicted to it can’t eradicate it, control it, and satisfy their addictions at the same time.

To see our running list of the top 100 greatest rock stars of all time, click here.