Israeli Filmmaker Ran Tal on Berlinale Documentary ‘1341 Frames of Love and War’

Ahead of Sunday’s world premiere of documentary “1341 Frames of Love and War,” which plays in Berlinale Special, Variety spoke to the film’s writer-director Ran Tal, and Israeli war photographer Micha Bar-Am, who is the subject of the film.

In some ways “Frames” continues Tal’s interest in Israeli history evident in his previous work, “What If? Ehud Barak on War and Peace,” which centered on the former prime minister of Israel. Bar-Am was born in Berlin in 1930, but grew up in what became Israel, and across a five decade-long career as a photographer he documented many of the major episodes – in particular the wars – in the life of the young country, founded in 1948.

More from Variety

“I wanted to do two films: one about a player in history […] and the second one should be about the witness,” Tal says. The filmmaker got in touch with Bar-Am, who showed him his archive of more than half a million negatives, stored in his basement in Tel Aviv. “It was clear to me immediately that I wanted to spend a lot of time in this basement,” Tal says. “It took me three years to assemble the film.”

Bar-Am and his wife Orna were “very friendly and honest, and opened their hearts, their house and the archive for me, but it took time to build this kind of trust, because I set as one of my conditions that: I want open [access to the] archive and I want to use any image I want. You don’t get to see the film until the end. You need to trust me,” Tal says.

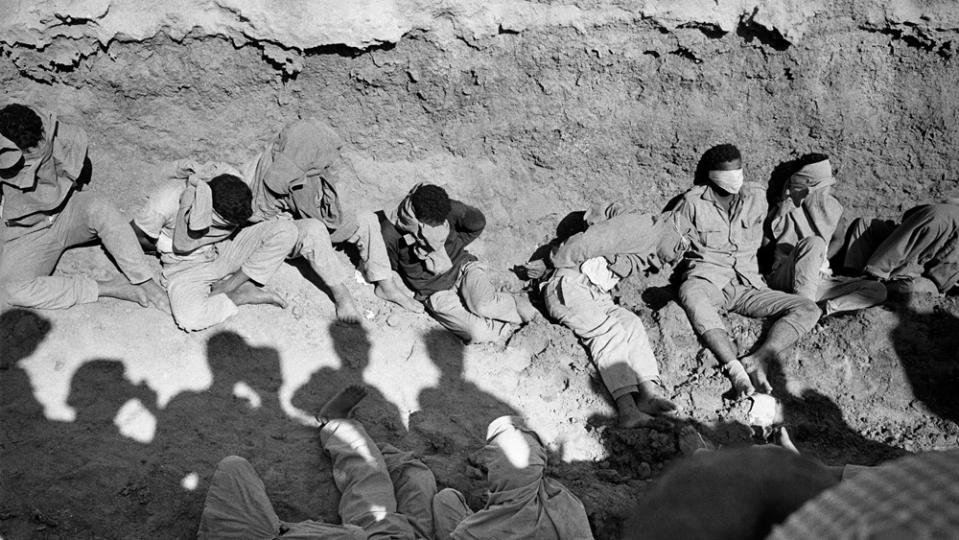

Courtesy of Micha Bar-Am

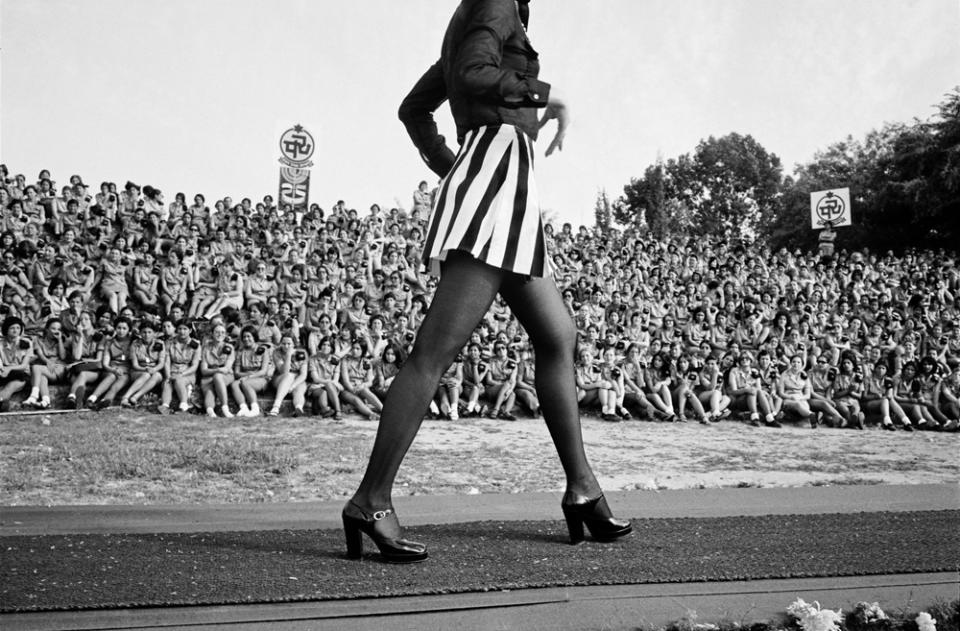

The film is almost entirely composed of the photographs that Bar-Am took over his career, and is accompanied by the conversations Tal had with the couple about the photographs and their recollection of the events and their feelings about them. Alongside the shots of the many military conflicts that Bar-Am covered during his career are intimate images of family life.

By only using Bar-Am’s still images the viewers see events through his eyes, and “see what he saw […] you can understand his mind.”

Bar-Am belonged to the elite group of photographers at Magnum photo agency, formed by Robert Capa and Henri Cartier-Bresson among others, and his work appeared in some of the most prestigious titles in the world, including the New York Times, Time magazine, Stern and Paris Match. Unlike the throw-away images of the Instagram era, Bar-Am’s photographs “try to tell you about complicated situations,” Tal says, and he was “inspired by that as a filmmaker.”

The conversations between Bar-Am and his wife Orna add “another layer to the film,” portraying the relationship between the couple. “Orna is very important to the Bar-Am project. Micha is the great artist and has been everywhere, but she is totally part of the game. She was always there: She was picking the photographs, she is the one that is creating the exhibitions many times, responsible for catalogues.” She has strong opinions about the events and ethical issues, so “it was important to have her voice and use these two characters to build new layers” within the film.

Courtesy of Micha Bar-Am

The film is principally about the photographer, but Israel itself plays an important role. “I think all my work is, in many ways, about the Israeli story, the Israeli project – to try to understand it from the inside, often from the bottom up,” Tal says. “It is about Micha, it is about photography, it’s about war, it’s about post-trauma, memory, age,” but the Israeli experience and history is also present. “It’s not about Israel, but Israel is always there.”

There is a progression in the film from the confidence and optimism of the early decades in Bar-Am’s career, to the doubt and questioning exhibited later, especially concerning the role of the Israel Defense Forces. Eventually, he stopped taking photographs altogether. “It came out in the recording of the talks. I really wanted to understand why he stopped. It is a really dramatic decision for an artist to stop making art, and in Micha’s case to stop taking images.”

Tal is now working on an installation based on the documentary that will open in Tel Aviv in June.

Speaking to Variety, Bar-Am downplays the impact he had on Israeli society and the perception of Israel abroad. “This is something that I was passionately doing, and I also happened to be able to make a living with the camera,” he says modestly.

“I don’t think that we photographers leave more than a scratch on the mirror. We try to reflect and actually we have the illusion that we really change reality, which is I think not true. Sometimes you make your impression on people, who can be impressed by your language, but I don’t think we photographers change anything.”

However, when he was young, he felt his photographs could change things. “Yes, I was na?ve enough to think so, but nowadays when everybody is a photographer I am not so sure that with a chaotic world around us photography can change anything.”

Courtesy of Micha Bar-Am

He is optimistic about Israel now. “Well, we will not go into anything political. Like many Israelis and other people around the world, I like this country. I am optimistic by nature. Even though there are darker periods with many question marks I don’t belong to the pessimists. I think you need to take a positive approach to life, even when it is down.”

He makes no bold claims for the artistic status of his work. “I didn’t go out to do art. I went out to do photography. To photograph is to record life as it happens around you, and because I have an adventurous nature, I really tried to make life also interesting to myself.”

One of the strengths of his work is that connection he feels with the people in his photographs. “You become part of the events you are photographing. You don’t have to sympathize, and you don’t always like what you see in front of your camera, but definitely I have a positive approach, and I like people, and I hope to see good things happening, and of course I was involved to be involved, but it doesn’t always happen.”

He says that photographers have to establish independence and “a certain distance” from those they are with, such as the soldiers he used to accompany on missions. “This is a paradox of people like myself who have to keep a certain distance in order to comprehend or to see not only the scene but also the whole scope of events around you. I don’t always agree or love what I see, but it is definitely important to record and then to analyze what you saw.”

Nowadays, he only takes photographs of his grandson, he says.

Courtesy of Micha Bar-Am

Best of Variety

Sign up for Variety’s Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.