'Jaws' at 50: Peter Benchley's toothy terror and the fascination with great white sharks

It's been 50 years since the late author Peter Benchley introduced us to "Jaws," a fictional man-eating great white shark that terrorized the summer resort village of Amity, Long Island, and our hearts and minds.

Perhaps the latter impact wouldn't have been so profound had the book not inspired the 1975 summer blockbuster of the same name directed by Steven Spielberg, starring Roy Scheider, Richard Dreyfuss and Robert Shaw. The movie's musical score composed by John Williams has no doubt ruined many ocean swims once the ominous "da duh, da duh, da duh," creeps into a bather's head.

"Everybody got spooked," recalls Paul Mila, a Jackson resident today and scuba diver who's seen great white sharks up close and personal on dive expeditions off the coast of Mexico.

Mila grew up in Brooklyn going to Coney Island and the Rockaways. He saw "Jaws" in the theaters the summer it came out with his wife. He said the entire audience took a deep breath when the head of Ben Gardner appeared in the hole of the sunken fishing boat. He said the movie changed people's behavior.

See a shark up close: NJ fisherman faced great white shark all alone off Jersey Shore, recorded encounter

"We were all going to the beach and three or four times you'd hear the lifeguards' whistles and we'd be called out of the water because somebody thought they saw a shark," Mila said. "It was never like that before."

"Jaws" changed us forever. But a lot has also changed since Benchley conjured up "Jaws."

A great fish villain is born

Benchley, who lived in Princeton from around the time the book came out until his death in 2006, said he could never write "Jaws" in the current world the same way he did when he wrote it. In 1994, in the introduction to the 20th anniversary reprint of his book he wrote that he "could never demonize an animal, especially not one that is much older, and much more successful in its habitat than man is."

Benchley said "Jaws," his debut novel, was the offspring of childhood passion. Growing up on Nantucket in the 1940s and 1950s, he would see the dorsal and tail fins of sharks crisscrossing the oil-calm surface waters around the island. He said they spoke of the unknown and the mysterious, of invisible danger and mindless savagery.

In 1964, he read an item in a newspaper about a charter fisherman, Frank Mundus, who harpooned an estimated 4,500-pound great white shark off Long Island, and the idea for the book's plot was born: a monster that came into a resort community and wouldn't go away.

It would be another decade before Benchley wrote the book, and in doing so he said he succumbed to the anecdotal evidence — exaggerated tales of sharks attacking boats, targeting humans or staying in one area just killing and killing.

Long history: Jersey Shore men may have found first recorded shark attack in North America

"In those days, we knew next to nothing about them. Now we've learned a whole heck of a lot," said biologist Greg Skomal, a leading shark expert in Massachusetts and co-author of "Chasing Shadows: My Life Tracking the Great White Shark," which seeks to set the record straight about great whites.

"Jaws," Skomal said, touched on some primal fear in humans from our long hunter-gatherer existence.

"I think it's an innate fear that has not evolved out of us. That is the fear of being killed by some wild animal. The bulk of our evolution was dealing with that. It's ingrained in us," Skomal said.

Skomal was 14 and growing up in Fairfield, Connecticut, on the shores of the Long Island Sound when "Jaws" came out. Matt Hooper, the fictional ichthyologist from Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution that came to Amity to study the shark, became the inspiration for his future career.

Another "Jaws" character influenced a generation of fishermen: Quint. In a 2015 interview with the Asbury Park Press a few years before he passed away, Harry Thorne said shark fishing was hot because of the inspiration of "Jaws." "Everybody wanted to go out and catch sharks." Thorne told the press.

Thorne was the owner and captain of the charter boat Temptation, which docked on the Manasquan River in the 1970s and '80s. It's the boat on which Jimmy Kneipp reeled in the New Jersey state record 759-pound great white shark in 1988.

Unsolved mysteries: Jersey Shore shark attacks of 1913 among highlights of new book

From fear to coexistence

In the years that followed the book and the movie (and its multiple sequels), Benchley blamed himself for the overexploitation of sharks. He became a conservationist and, along with his wife, dedicated the rest of his life to raising awareness about sharks.

"I think Benchley was way too hard on himself. He wrote a great horror story and it turned into a great horror movie. I don't think anyone who's written a horror story about giant ants felt the need to apologize for it," said Skomal. "He thought the demise of shark populations had a lot to do with his book and that's just not the case. He can take some responsibility for making a lot of people scared of sharks. You still meet people afraid to go swimming because of 'Jaws,' and that's just nonsensical."

Sherri the shark: Great white shark surprised NJ boaters, gets named Sherri after fisherman's mom

Overexploitation of fish populations is a theme around the world, but for sharks in particular, one of the most damaging practices is shark finning, that is killing sharks solely for their fins. The practice is now banned by many countries, including the United States, but not by all.

Regrading great white sharks, the United States prohibited fishing for them in 1997 and the species has slowly but steadily rebounded due to the fishing prohibitions but also the federal protection on their favorite meal: pinnipeds, commonly known as seals.

"White sharks are rebounding. Whether they are 100% restored to their historic levels, we don't quite know," Skomal said.

As an apex predator, the great whites create a delicate balance in the ecosystem between their populations and the seals. It has been cause for some concern, especially after a boogie border was fatally bitten by great white six years ago off Cape Cod, followed by another fatality in Maine in 2020.

More: Shark attacks climbed in 2023, and Jersey Shore saw its first bite in over 10 years

"You still have a lot of people fearful of sharks, but I think there has been shift in attitudes from 100% fear to one of fascination," said Skomal. "When you get an event like Cape Cod in 2018, there's always going to be some backlash because there's a victim and the victim's family and repercussions to the local economy. But then it kind of slips into the back of people's minds. It's been almost six years without a bite off Cape Cod and the people have come around to acceptance of the sharks and a kind of coexistence with them."

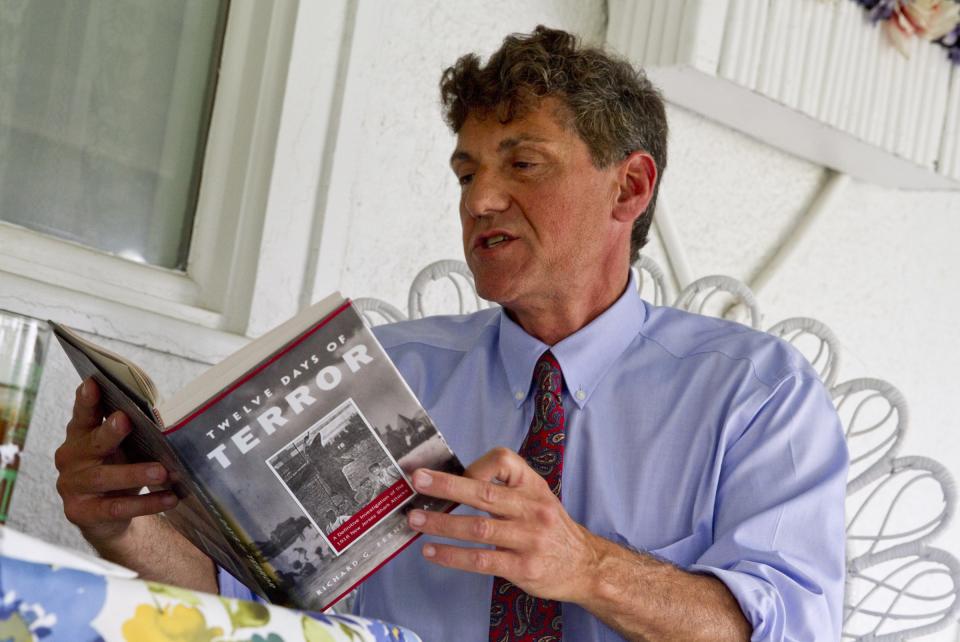

Allenhurst author Richard Fernicola is one of the Jersey Shore's expert voices on the Jersey Shore shark attacks of 1916, which killed four and wounded another. The event was referenced twice in Benchley's book. Whether it was one great white shark or multiple species that was responsible for the attacks no one can absolutely say, but the story has come down in history as a rogue great white.

At the height of the fear in 1916, farmers and their wives were shooting at shadows in the Matawan creek.

Matawan shark attacks: A century later, shark attacks still echo

Fernicola, who authored "12 Days of Terror," an account of the 1916 shark attacks, said unknowns about the great white shark contributed to inappropriate responses in the past. Today, there is a shift to science and the public seems to be on the same page about acquisition of data, he said. That acquisition of data has led to a few conclusions, one of which is that the vast majority of coastal shark attacks are cases of mistaken prey identification.

"Today, serious or fatal animal attacks are not reflexively greeted with fear and panic. Although public safety remains the paramount concern, understanding of the event takes priority," Fernicola said.

While a shark bite may not cause public hysteria, closing the beaches is still one of the actions often taken by local, county, state and federal governments. Walton County along the Florida Panhandle closed several miles of beaches following three shark attacks that occurred on June 7. Law enforcement and Florida Fish & Wildlife patrolled the waters with boats and helicopters much like in "Jaws."

Mary Lee the shark

If "Jaws" terrified the public, Mary Lee stole their hearts.

One of the elements that makes great whites so feared by people is their element of surprise. It is impossible to predict where or when they will show up. In the water, their color is to their advantage. Their top sides are shaded grey or dark blue while their underbellies are white. This contrast makes them appear like shadows as the dorsal area blends with the sea color from above and the underbelly poses a silhouette against the sunlight.

"They're super stealthy. They're invisible. If they don't want you to see them, you're not going to see them," said Chris Fischer, founder of OCEARCH, a nonprofit research group that has been tagging great white sharks on the East Coast for over a decade to study their life cycle.

Fischer said the young pups up until their 20s have clean and nearly perfect skin. But when they turn mature and start mating in the 30s, the battle scars begin to appear.

"Mating is violent and then they start to eat a lot of seals. Their faces are just covered in scratch marks from seals trying to claw themselves away," Fischer said.

Some of the mature sharks he's handled are 50 years old or more. They survived humans trying to kill them in the 1970s and '80s.

"It's like, 'Wow, you survived us.' You are the most clever of genetics. And then you feel so small and stupid for what we did," Fischer said.

With the use of satellite tags and OCEARCH's Global Shark Tracker App, the public for the first time was able to follow the movements of the great whites as they migrated up and down the East Coast. It peeled away at some of the sharks' mystique.

'We were amazed': Huge great white shark surprises stunned NJ fishermen

In 2012, one of those sharks, Mary Lee, a 16-foot, 3,500-pound mature female, captivated the coastal communities she swam to.

"Mary Lee undid everything 'Jaws' did on the East Coast of the United States," Fischer said. "She traveled up and down the East Coast, poking her nose in all sorts of rivers and estuaries. People starting watching her and started saying 'Oh Mary Lee, come here next or don't leave.' People began to see that we've been swimming with these white sharks our whole lives. We just didn't know. We knew nothing."

The battery on Mary Lee's satellite tag most likely went dead in June of 2017. The last place she her beacon transmitted was right off the coast of Beach Haven, a town that is no stranger to sharks. It was here where the first shark attack in the summer of 1916 occurred.

OCEARCH meanwhile has tagged 92 great whites in 46 expeditions, and while Mary Lee went silent seven years ago, there are dozens more with colorful nicknames to follow, including biggest of all, Nukumi, a 17-foot mature female. Fischer said the tagged sharks has helped educate the public.

"I think the East Coast now has the most mature disposition in regards to its sharks," Fischer said.

When Jersey Shore native Dan Radel is not reporting the news, you can find him in a college classroom where he is a history professor. Reach him @danielradelapp; 732-643-4072; [email protected].

This article originally appeared on Asbury Park Press: 'Jaws at 50': Peter Benchley's great white shark book still fascinates