Jazz Legend Charles Lloyd Is Still Making Fresh Music

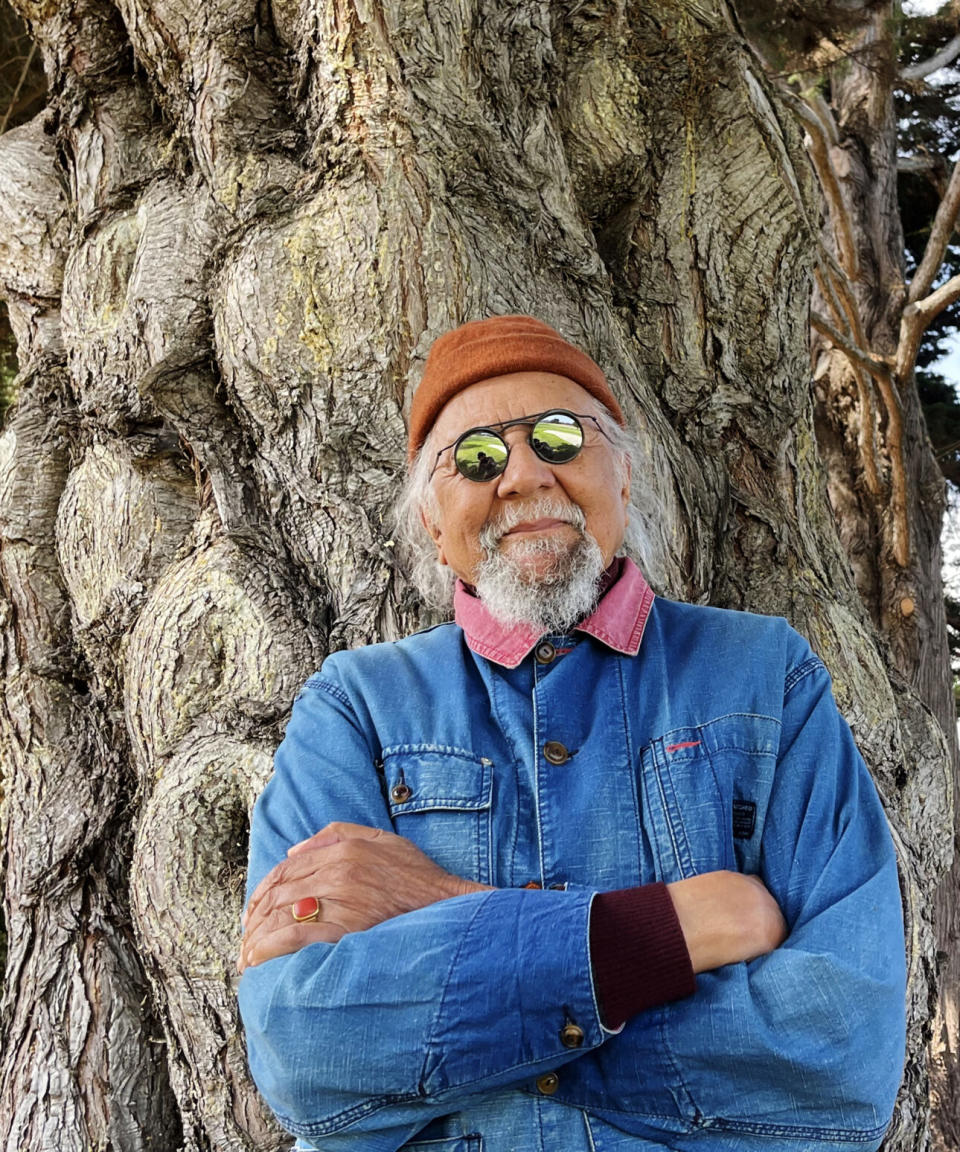

It’s a little chilly, cotton-ball clouds against the blue sky, the air crisp and fresh coming off the Pacific. Charles Lloyd, in a caramel-colored stocking cap, silvery parka, and socks-less Birkenstocks, stands on a rooftop deck at his home in the hills near Santa Barbara, surveying the stunning view down to the sea. The venerable jazz sax and flute player and composer has lived here with his wife, Dorothy Darr, for about 25 years.

“She made all this,” he says, proudly, of Darr, who designed the gorgeous, adobe-style house.

He and Darr, who is his manager/producer—and a noted artist, photographer, and filmmaker—have called this home for half of the time they’ve been together. He remains invigorated by the setting.

“Check this out. People said, ‘You don’t want to move out there. It’s too far out of the village.’ I said, ‘Great!’ Because I used to play with them old blues cats and they would sing, ‘Going to move way out on the outskirts of town. I don’t want nobody coming out there, messing around.’ You know what I’m saying? Yeah. And it is beautiful.”

He is surrounded with beauty, outdoors with nature and indoors with art. Later, walking through, he points gleefully to a dream-like painting by Darr of him with sleeping elephants and a striking black-and-white photo portrait of pianist Art Tatum, a gift from Newport Jazz Festival founder George Wein after Lloyd had admired it at Wein’s New York home.

Up on the deck, he sweeps his arm at the view, a look of deep contentment on his face, and then moves inside a small office —“The Skybox,” he calls it.

He’s got his life here with Darr. He’s got the view. He’s got his music, He’s got the sky above it all. He has even titled his new album The Sky Will Still Be There Tomorrow.

“So the sky is always, like, the closer I get to it, the Creator says, ‘Not yet, Charles.’ ” he says of the title, seated in a desk chair, legs stretched out. “So I’m just still here working on it. But the benefit of that is that it gives me gratitude and humility to know that I still got a long way to go.”

Keep in mind that he just turned 86 on March 15. That was also the release date for Sky, the Memphis-born Lloyd’s 51st album in a singular career rooted in jazz but re-defined and re-shaped in his own terms at every turn through the years.

A long way to go? He means it.

“I’m still like, I got beginner’s mind, but I’m still in the now, you know? I don’t have the ability to fossilize stuff. I’m not interested in that. I mean, I like the whole historicity of it all.”

He smiles impishly. “But I still like to go exploring, because when you go exploring you don’t come back the same. And something about that I like, you know?”

He’s just as excited and invigorated by music as he is by where he lives. That attitude has helped Lloyd keep up a remarkable level of creativity throughout the decades, as much or more now than even in his heady youth. For that, last year, at 85, he was named Artist of the Year by the core jazz publication DownBeat—making him the oldest recipient of that honor since the magazine started its annual awards poll around the time Lloyd was born.

“Well, it’s a beautiful thing, isn’t it?” Lloyd says, a sparkle in his eyes coming from behind his stylish round glasses. “And they gave it to me when I was a little boy!”

Indeed they did. In 1967 he was what was then called DownBeat’s Jazzman of the Year at age 29, when he was leading a quartet featuring then 21-year-old pianist Keith Jarrett and then 25-year-old drummer Jack DeJohnette, both giants-of-jazz-to-be themselves. That ensemble set new standards in jazz, combining stunning melodic sense, forceful rhythmic power, and mind-blowing improvisational flights that won over not just jazz heads, but rock fans too.

Getting that DownBeat honor again 56 years later is an unmatched feat. This is not an award honoring a legacy. It’s a recognition of current artistry and achievement, which continues to grow on the new album with his latest quartet—pianist Jason Moran, bassist Larry Grenadier, and drummer Brian Blade.

And this is just the latest in a remarkable run of achievements in the last decade since Don Was, a big Lloyd fan who had become president of the vaunted Blue Note label, recruited him to join its roster, giving him complete creative freedom. Lloyd has turned that promise into standout work. Last year he released his Trio of Trios—three bracing albums teaming him with guitarist Bill Frisell and bassist Thomas Morgan, pianist Gerald Clayton and guitarist Anthony Wilson, and guitarist Julian Lage and tabla player Zakir Hussain, respectively. And before that there were three albums with his Americana-tinged ensemble the Marvels, featuring Frisell and steel guitarist Greg Leisz alongside Lloyd’s bassist Reuben Rogers and drummer Eric Harland from his quartet of the time. One of those was 2018’s Vanished Gardens, a sparkling collaboration with singer-songwriter Lucinda Williams.

In this time he was named an NEA Jazz Master in 2015, awarded an honorary Doctor of Music from Berklee, inducted into the Memphis Music Hall of Fame, awarded the French honor l’Ordre Chevalier des Arts et des Lettres in 2019, and given the Lifetime Achievement award last year by the Jazz Journalists Association.

“This 50-, 60-year gap, people still think I’m working on something, you know?” he says, a youthful electricity charging through him as he talks about what keeps him going. “And I am. It comes through me. I’m just a reporter. I’m just trying to shed some light here.”

That mission and that drive have taken him to many places, artistically, in the years between the DownBeat awards, with some interesting twists. He spent part of the 1970s living in Big Sur, outside of the jazz world, fed up with the “plantation system” of the music biz, as he put it, and disconnecting some bad habits he’d indulged in with such pals as Jimi Hendrix and Peter Fonda. For part of the decade, befriended by Mike Love, he recorded and toured with the Beach Boys (there’s a great live clip on YouTube from 1977 of “Feel Flows” featuring a spectacular, six-minute Lloyd flute solo). In the ‘80s, signed to the German ECM Label, he expanded his jazz language, collaborating with Hussain, Greek singer-composer Maria Farantouri, Swedish pianist Bobo Stenson, and an array of American artists including John Abercrombie, Billy Higgins, and young pianists Gerald Clayton and Moran. His voracious curiosity and hunger for new horizons took full flight through it all.

The thing is, he had this drive even when he really was a little boy, in Memphis in the mid-1940s.

“We had a big house and the musicians would come to town,” he says, recalling Jim Crow segregation. “There were no hotels for them, so Duke Ellington and Johnny Hodges, all those people, would stay with us. I was drunk”—he uses that term in the emotional sense, not the alcohol-fueled sense—“because I was playing music before they came. My mother told Duke Ellington I wanted to be a musician. He said, ‘No. Make that boy be a doctor, a lawyer, an Indian chief, because this stuff is too hard a life.’ But I was bit by the cobra, so there was nothing I could do.”

By his teens, alongside his best friend, trumpeter Booker Little, he was getting sideman gigs with blues and jazz artists coming through town, Bobby “Blue” Bland, B.B. King, and Howlin’ Wolf among them. The grit and demands of those performances stayed with him through the ‘50s as he studied composition at USC in Los Angeles by day and played in the city’s smoky Central Avenue clubs at night with Ornette Coleman, Charlie Haden, Eric Dolphy, and others who were pushing the West Coast scene into new territories. Those experiences and musical ambitions laid the foundation for the artistic and popular success of that ‘60s quartet.

And now, with Sky, he’s revisiting the quartet format as he has regularly in his career, setting a fertile ground for the fruits of his explorations, a home to his ever-expanding sense of expression. Moran and Grenadier have been his frequent collaborators over the last couple of decades. Newer to the fold is Blade, whose distinctive, almost orchestral approach to percussion was a big part of the last quartet led by Wayne Shorter, a close friend and great inspiration to Lloyd. In fact, Blade’s mystical rumbles provide the new album’s invocation, the first sounds heard on the opening piece, “Defiant, Tender Warrior,” before Moran’s colors-rich piano, Grenadier’s vocal-like bass, and Lloyd’s pure, warm tones and imaginatively evocative solos.

“I said to Dorothy about three years ago that I wanted to make an album of tenderness and bring some tenderness into the world,” Lloyd says. “And this is the cast of characters that I wanted to do it with.”

With some delays due to the pandemic and scheduling, the four were able to gather at Lloyd’s home studio to create the music and then played a concert at Santa Barbara’s Lobero Theater to mark his 85th birthday. The album is a mix of new compositions with several pieces drawn from his vast past catalog that were ripe for reworking and freshening by this lineup. The magic is that it’s hard to tell the old from the new, so fresh does it all sound, so in the moment. “Well, I’m not gonna bore myself,” Lloyd says. “So why would I bore other people?”

There is tenderness in it, but also power and playfulness, woven with links to the past and the present, tributes and homages to figures who had impact on him—“Monk’s Dance” for Thelonious Monk, with whom he shared a stage numerous times; “Cape to Cairo” for Nelson Mandela; “Defiant, Tender Warrior,” on which his playing carries the spirit of Lester Young—as well as enveloping interpretations of gospel classics “Balm in Gilead” and “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” anthems of the Civil Rights movement.

A quarter of the way through the generous double album is a short piece, just one minute, Lloyd duetting with himself on alto and bass flutes. It’s called “Late Bloom.” It seems [like] a funny title, a bit of a wink. He’s been blooming throughout his life.

“Yeah,” he says. “But the deep stuff has started to come.”

What follows “Late Bloom” justifies that claim, the brief bit serving as prelude to the emotional heart of the album, Lloyd’s tribute to someone who bloomed early and then was gone: his friend Booker Little, who died in 1961 at age 23 of kidney disease, just as he was emerging as one of the leaders of jazz’s next era. “Booker’s Garden” is a moving impression, a highly personal expression of Little’s spirit. It’s not somber or sorrowful, though. It’s a celebration of his continued presence in Lloyd. Just the mention of the piece sparks bright memories of that time, when Lloyd had just arrived in rocking New York, fresh from his USC and Central Avenue apprenticeships.

The move east was to join Chico Hamilton’s quintet, in which he replaced Dolphy. He booked a room at the Alvin Hotel, a “funky” place where the musicians stayed, he says, across from the Birdland club in the heart of Manhattan. It turned out that Little, touring with drummer Max Roach, was playing Birdland that very night—though Little, on hearing that his friend was staying in that hotel, insisted that Lloyd check out and come stay with him.

“I’d been out on the [West] coast with Ornette [Coleman], Scott La Faro, and [Billy] Higgins and [Don] Cherry and all that, and playing in Gerald Wilson’s big band and with Harold Land,” he says. “It was a rich community out there too. But when I got to New York, that was Mecca.”

Lloyd admits that he, 22 then, was dazzled by the pace of the city.

“I was blessed to be with Booker,” he says. “He pulled my coat, you know? I was ready to jump in the fast lane. He said, ‘No. It’s not about that. It’s about character.’”

Soon Lloyd hit the road with Hamilton, and before he got back, Little had, as he puts it, “left town.” But Lloyd views this now with a Buddhist perspective.

Booker, he says, was a “realized soul. He was an avatar. An avatar comes here to do some road work, and then they go back home.”

Little is still there for Lloyd to call on, though.

“I still communicate with him,” he says. “I was sitting down there, and he brought me a scale a little while back. It was a lost scale. I was playing my alto flute, and I was sitting downstairs, and I said, ‘Oh, Booker!’ So I have these metaphysical, mystical things that happen to me.”

His ode to Little leads into “The Ghost of Lady Day,” his nod to Billie Holiday, who also didn’t get to have a late bloom. And following that is the album’s title piece, a balance of meditation and frisky play showing his appreciation to still be here under that sky which will survive us all.

Once more he addresses the meaning of the piece and its title.

“That comes from something….” He hesitates. “Well, you know, it’s the last night of the play at the end of the journey. I’m like an elder or something, and I’m like a dream of a better world. We never got it, you know? Still throwing rocks at each other thousands of years later. These people haven’t behaved. So my ideal—not ideal, but my naive notion was to change the world with the beauty of music. And it never happened. That’s why I went up to Big Sur. I decided if I can’t change the world, I’ll change myself. My mom messed me up when I was little. She said, ‘I don’t care what you be or do. Just be the best at it.’ ”

He pauses again. “Well, you know, I haven’t achieved that either.” He laughs, heartily. “But I can keep exploring.”

To see our running list of the top 100 greatest rock stars of all time, click here.