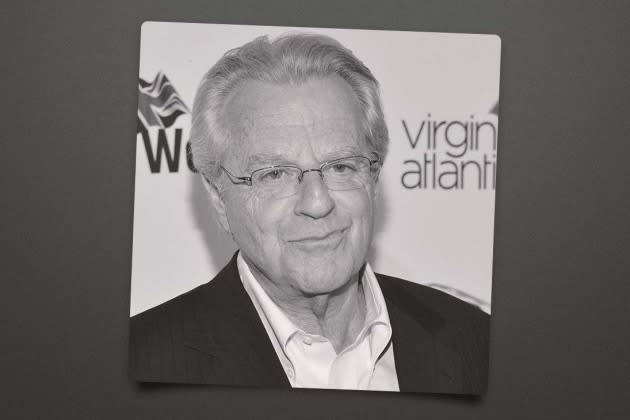

Jerry Springer, Host of a Scandalous Talk Show, Dies at 79

Jerry Springer, the former Cincinnati mayor who became America’s most controversial talk show host — a man described by one interviewer as a “purveyor of the puerile and arbiter of the aberrant,” famous for a combustible cocktail of hurled insults, punches and chairs — has died. He was 79.

Springer died Thursday of pancreatic cancer at his home in suburban Chicago, family spokesperson Jene Galvin told The Hollywood Reporter.

More from The Hollywood Reporter

“Jerry’s ability to connect with people was at the heart of his success in everything he tried, whether that was politics, broadcasting or just joking with people on the street who wanted a photo or a word,” Galvin said in a statement. “He’s irreplaceable, and his loss hurts immensely, but memories of his intellect, heart and humor will live on.”

For almost three decades, from its launch in 1991 until its cancelation in 2018, his eponymous program became synonymous with gutter viewing. The Jerry Springer Show was ranked No. 1 on a TV Guide list in 2011 of the worst shows in the history of television, beating out such dubious competition as Cheaters and Temptation Island.

In one episode, a purported sex worker lost her dentures when she got into a fistfight; in another, mother-and-daughter dominatrices brought out their “slave” and rode him around the studio. In two other shows, Springer welcomed women who claimed to have broken sexual records: one claimed she’d had sex with 30 men in the space of a few hours, the other that she’d fornicated with 251 men in a similar time frame.

These characters (or caricatures) were interviewed by Springer with genial tolerance, an air that mingled sympathy, amusement, intelligence and wry detachment, perhaps because in his heart of hearts he considered his day job beneath him.

“My passion is politics,” he told Men’s Health magazine in 2015, “and I’ve always been able to separate how I make a living from my passions.”

That was not strictly true: the two did collide in 1974, when the political and the prurient came together in an incident that derailed Springer’s dream of becoming a major politician. Then a Cincinnati councilman, he was found guilty of soliciting prostitutes (astonishingly, he had paid them with checks) and forced to resign, his long-term hopes of being a governor or U.S. senator shattered.

Gerald Norman Springer was born on Feb. 13, 1944, in a London subway station that was used as a shelter during bombing raids. He was the son of a bank clerk and a shoe shop owner, two Jewish refugees who had fled Germany.

“All of our family was exterminated by the Nazis, but my mother and father survived,” he said. “The train stations were used by people as shelter, and that was where I was born.”

Springer’s family moved to New York when he was 4, and he remained there until taking his degree in political science at Tulane University. After attending Northwestern law school, he worked on Robert F. Kennedy’s presidential campaign (cut short by RFK’s 1968 assassination) before taking a job with a Cincinnati law firm, Frost & Jacobs.

He was innately and irrepressibly liberal. “If you are a child of Holocaust survivors, it’s hard not to be a liberal,” he said. “Twenty-seven members of my family were wiped out. You learn that you never judge people on what they are, but what they do.”

At age 26, he became the Democratic Party candidate for a Cincinnati congressional seat; running against Donald Clancy, a four-term incumbent, Springer — who was also an Army reservist — lost but managed to get 45 percent of the votes. He was elected to the city council in 1971 and was, by all accounts, effective and popular.

“Wearing bell-bottom blue jeans, he spent a day working with a garbage collection crew, hauling cans from the curb and dumping the trash in the back of the truck,” noted one local reporter. “When the city took over the local bus service, he hijacked a bus during the Fountain Square ceremonies and drove it around the block. He spent a night locked up with prisoners at the old jail, a dungeon known as The Workhouse, saying he wanted to hear their problems and bring attention to their plight.”

After being re-elected, he was in line to become mayor (Democrats and Republicans had agreed to rotate the position), which would have made him the country’s youngest big-city mayor. Then came the prostitution scandal, triggered when the police raided a massage parlor and found a bad check pinned to the wall with “for services rendered” written on it.

The 30-year-old issued a statement: “It is with deep personal regret that I am announcing today my resignation from City Council. I understand what I am giving up, an enormous opportunity to share in the leadership of this great city. However, very personal family considerations necessitate this action. My family must and does come before my own personal career. Thank you all for all you have given me. I hope I have offered something positive in return.”

A day after he quit, Springer had to testify at the trial of two men accused of operating a Kentucky “health club” in which the evidence included one check for $25 and another for $50 that he had given for sexual services.

Springer’s then-wife, Micki, said she didn’t want him to resign, even though she had fled his news conference in tears. (They remained together until 1994.) “While what Jerry did was wrong, it’s nothing to throw your life away for,” she said. “I know what Jerry needs to stay alive. I just love him and I can’t bear to see him broken like this.”

Remarkably, Springer made a comeback when he was reelected to the council and subsequently named mayor in 1977, largely because he had apologized and addressed the matter front-and-center in his advertising. “When I think of being flat on my back three years ago, having this happen is almost unbelievable,” Springer said, with no evident attempt at irony. “This is the best feeling I’ve ever had in my political life.”

In 1982, he ran unsuccessfully to become governor of Ohio and then left politics for journalism.

During his student years, he had contributed to a local radio station and had continued to do so as a commentator for Cincinnati’s WEBN-FM. Joining local NBC affiliate WLWT-TV as a reporter and commentator, he soon rose to become anchor and for five years was the most popular newsman in the city, famous for his nightly commentaries. That paved the way for his talk show.

The Jerry Springer Show debuted in syndication in September 1991 and took aim at The Phil Donahue Show. Donahue was a liberal icon, a longtime talk show host whose affable manner and tolerant style eventually ceded its place to reality TV and sensationalist rivals.

In 1994, after struggling in the ratings, Springer and his producer took a leap in the dark: they decided to remake the show, turning away from such liberal themes as guns and homelessness and toward something altogether more tabloid.

Almost overnight, Springer’s program surged, and by 1998 it was beating even The Oprah Winfrey Show. Its set was revamped to make it softer and brighter; the host’s entrance was changed — he now slid down a stripper pole; and the theme of each installment was titled toward the lowest common denominator, with titles such as “Stripper Wars” and “I Want My Man to Stop Watching Porn.”

Some episodes defied belief, like the one in which a guest claimed to have chopped off his penis so a male stalker would not be able to touch him. Even that paled beside one who Springer called “the most bizarre story we’ve done” — about a transsexual who cut off her legs with a power saw.

Compared to these eyebrow-raisers, other highlights (lowlights?) seemed tame: There was one show with a man who bragged that he’d slept with his stripper sister and another with a fellow who said he wanted to marry his horse.

For dabbling in such subjects, Springer was extraordinarily well paid: in 2000, a contract renewal gave him $6 million per year. But for that money he had to endure not just opprobrium but also serious scandal.

In the same year his contract was extended, a 52-year-old woman who had just appeared on his show was found beaten to death. The victim, Nancy Campbell-Panitz, had been on an episode titled “Secret Mistresses Confronted” in which her ex-husband and his wife accused her of stalking them. The husband was subsequently convicted of her murder. Springer refused to share responsibility for the incident and told CNN that it “had nothing to do with the show.”

But that marked a turning point for the host. Afterward, concerned groups such as the Parents Television Council increasingly challenged what he was doing and urged advertisers not to sponsor the production, which damaged him hugely when he considered a return to politics. He weighed running for senator in 2000 and 2004 but chose not to go ahead in the face of too much hostility.

Springer ventured into other territory as a producer, host and actor. He presided over America’s Got Talent for two seasons, did Springer on the Radio for almost two years and hosted the Miss World and Miss Universe pageants on a few occasions. He also made cameo appearances on series from Roseanne to The X-Files, competed on Dancing With the Stars and even covered the U.S. presidential election for a British morning show in 2016.

Perhaps most impressively, he had a stage production based on his life, Richard Thomas and Stewart Lee’s Jerry Springer: The Opera, which ran in England for 609 performances and won the British version of a Tony, an Olivier Award, as best musical — which did not prevent 55,000 people from lodging complaints when it was broadcast on British television.

None of this came close to overshadowing The Jerry Springer Show, which continued until it ran out of steam after 27 seasons, when he segued to a new program, the syndicated Judge Jerry, in 2019.

Survivors include his daughter, Katie, a child born legally blind and deaf in one ear, and a son-in-law, grandson and sister.

Springer’s various ventures might have cost him his dreams, but they made him a fortune, for which Springer remained defiantly unapologetic. After everything his family had gone through, survival, ultimately, was more important than the ethics of a mere TV show. And yet he defended even the morality of what he was doing in a 2008 commencement address at Northwestern’s law school.

“It is perhaps inevitable that we are inclined to always judge others,” said Springer. “But let me share this observation. I am not superior to the people on my show, and you are not superior to the people you will represent. … Unavoidably, you will all join me on this witness stand of conscience, trying your best to figure it out — never perfectly but, hopefully, always sincerely.”

Stephen Galloway is dean of the Chapman University film school.

Best of The Hollywood Reporter

Solve the daily Crossword