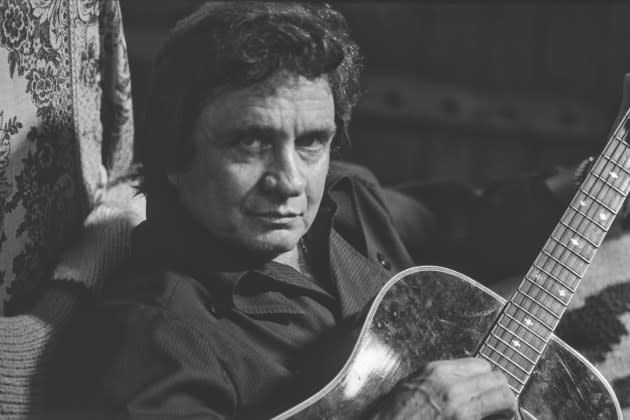

New Johnny Cash Album ‘Songwriter’ Asks, What If the Man in Black Never Met Rick Rubin?

On the cover of American Recordings, Johnny Cash’s stunning 1994 comeback album, the Man in Black stands squarely between Sin and Redemption — literally, since that’s what he named the black-and-white dogs that flank him as he glares into your soul. At the time, he also felt between sin and redemption metaphorically and the album was a leap of faith. The new archival compilation, Songwriter, which contains demos Cash recorded in 1993 mere months before American Recordings, presents an alternate history of the period when absolution still felt unattainable, and many of the songs find Cash treading water in the same low tide that nearly parched his career in the Eighties and early Nineties.

The key to understanding the whole compilation is held in “Like a Soldier,” a tune of survival that Cash recorded both in the Songwriter and American Recordings sessions. On the tune, he sounds flabbergasted that he’s even singing at all: “I said a hundred times I should have died,” he grossly understates in one lyric, while in another, he beams, “my spoils of victory is you,” surely a nod to his long-suffering wife, June Carter Cash. Its verses are brutally stark, but when he recorded it for 1994’s American Recordings, he sang the chorus, “I’m like a soldier getting over the war,” with hope glimmering through the gravitas of his basso profundo. He sang it plainly — no electric guitar chickaboom, no galloping snare, no Ennio Morricone soprano wafting behind him — it was just his voice and his guitar, lyrics and chords. It’s intimate and inspiriting.

More from Rolling Stone

Black Keys' Dan Auerbach Featured on New Johnny Cash Song 'Spotlight'

Johnny Cash Finds Love at the Laundromat on Posthumous Song 'Well Alright'

Hear Bob Dylan Cover Johnny Cash's 'Big River' For First Time in 21 Years

When he recorded the song for the Songwriter session, though, he had decided to keep it to himself. It’s big and welcoming and it lacks punch, and he knew it.

After refusing to hop on the urban cowboy and outlaw country bandwagons of the Eighties, the big river that was once his career had trickled down to trough drippings (not counting the Highwayman albums). His label wanted nothing to do with him, so he tried to blow up his whole career with the self-parodying “The Chicken in Black” in 1986, and when he tried to get serious on another label, the records bombed. (Water From the Wells of Home still sounds great, though.) Cash would’ve retired if he didn’t feel obligated to provide for his musicians and family, according to Robert Hillburn’s 2013 biography.

So Cash continued touring and writing songs, and eventually he met producer Rick Rubin in 1993. Rubin was best known at the time for Beastie Boys, Red Hot Chili Peppers, Slayer, and Andrew “Dice” Clay records. Somehow he convinced Cash that he understood country, too. He saved Cash’s career simply by asking Cash to sing his favorite songs with only a guitar accompanying him, and those songs became American Recordings. In his autobiography, Cash described the sound as “late and alone in a room,” but the austerity of the sound, coupled with a few comically macabre lyrics (even for Cash), turned him into an alternative icon at age 61.

So Songwriter asks the question: What would Johnny Cash have sounded like if he’d never met Rubin? In early 1993, the same year he met Rubin, Cash and various band members cut around a dozen demos of songs he’d written at LSI Studios in Nashville. For Songwriter, Cash’s son, producer and guitarist John Carter Cash wiped everything from those sessions (including, sadly, W.S. “Fluke” Holland’s drums) except for Cash’s voice and assembled musicians to rerecord the instrumentation with guest appearances by Vince Gill, Marty Stuart, and the Black Keys’ Dan Auerbach. His intention was to give the recordings a supposedly more modern sound — but it still doesn’t match up to the cowboy-boot heel turn of American Recordings.

The songs themselves are a mixed bag, some showing promise and others showing disillusionment. “Like a Soldier,” as a song, still sounds moving, but it begins with an electric guitar turnaround that calls back to the opening bars “Folsom Prison Blues” and “I Walk the Line.” Waylon Jennings sings backup vocals, sweetening the chorus, but even those flourishes and the lush instrumentation lack the power and immediacy of the better-known American Recordings version.

Similarly, “Drive On” — another tune Cash didn’t feel comfortable recording officially until he met Rubin — bears sort of a Three Dog Night, “Mama Told Me (Not to Come)” psychedelic swamp-rock arrangement that undercuts the directness of the Rubin version. Had these songs come out in this format, they might still be beloved, but they wouldn’t have packed the juggernaut punch they did with just Cash’s voice and guitar.

In 1991, Cash had released his last pre-Rubin album, The Mystery of Life — a record he thought so little of he didn’t type the title correctly in his autobiography, misnomering it The Meaning of Life. Its big arrangements sound like Cash-by-numbers, and the Cash originals, other than rerecordings of “Hey Porter” and “Wanted Man,” sound just as uninspired. The novelty song “Beans for Breakfast” (as in “Beans for breakfast once again, hard to eat ’em from the can”) lands a notch about “The Chicken in Black,” showing where his state of mind was at the time. So it’s curious to think he was selfishly holding onto actually great songs like “Like a Soldier” and “Drive On.”

Ironically, the best songs on Songwriter that Rubin did not later record for American or its sequels have a novelty feel to them. The rockabilly pickup line, “Well Alright,” finds Cash chatting up a woman at the “laundry mat,” eventually taking her home — well, alright! He hums “mmm-mmm-mmm,” and Stuart’s guitar echoes the melody back at him, making for a song that needs bigger instrumentation. Meanwhile, on “She Sang Sweet Baby James,” Cash narrates the tale of a trucker mother separated from her child, singing James Taylor’s “Sweet Baby James” to comfort herself. He even sings highly and lullaby-like similar to Taylor (a feat for Cash), and the song likely could have benefited from a lighter arrangement like Taylor’s “Sweet Baby James,” rather than the spaghetti Western tremolo mandolin on Songwriter.

The rest of the songs are good, but none of them glisten like lost gems plucked from Cash’s blandest era. The lost-love elegy “Spotlight” benefits from Auerbach’s bluesy guitar solo, but the music largely doesn’t live up to Cash’s moving lyric, “Let me feel like losing her will be all right.” “I Love You Tonite,” which also features Jennings, is a sweet love song to June, but the loping percussion and whining steel guitar still sound dated even if they were recently recorded, while another ode to June and her mother, “Poor Valley Girl,” echoes the Fifties. A rerecording of “Sing It Pretty Sue” sounds good enough but never bests the original from 1962’s The Sound of Johnny Cash.

The collection’s biggest misfit, “Hello Out There,” finds Cash singing cosmically about Earth losing its luster echoing his own lyrics over a skipping triangle (as in the orchestra instrument) rhythm before pivoting to a hymn about the King restoring Earth’s realm. The original demo is still online, and while it lacks some of the drama of the new recording, specifically the religious heel turn in the bridge, it shows that Cash’s mindset at the time was still focused on towing the line of bland and bloated middle-of-the-dirt-road country he hitched himself to in the early Eighties.

The title of the collection, Songwriter, suggests John Carter Cash wanted to display his father’s ability as a songwriter, a talent that was well proven by the time he wrote these songs. The Nashville Songwriters Hall of Fame had already inducted Cash in 1977, pointing to songs like “Folsom Prison Blues,” “Get Rhythm,” and “I Walk the Line” as reasons for induction. None of the songs here rise to the level of those classics. Instead, they show Cash parsing his place within the strata of country music at a time when Billy Ray Cyrus and Garth Brooks were bridging two-chord, Cash-bred traditional country with pop music for untold success and he was still the Chicken in Black.

Cash likely would have continued spinning his wheels — and holding onto his best songs — had he never met Rubin. In that regard, Songwriter is like an alternate universe American Recordings — one that also overlooks Cash as a great interpreter of others’ songs (see: “Solitary Man,” “Hurt”). Fortuitously for Cash, and the rest of us, the planets aligned in this universe setting Cash up for one of music’s greatest final acts.

We’re changing our rating system for album reviews. You can read about it here.

Best of Rolling Stone