“I just knew Trevor Horn as a pop producer. When he turned up with a guitar, I said, ‘Is that a prop, or are you going to use it?’ We just didn’t hit it off”: How Yes’ 90125 became a triumph – despite starting with “the worst jam in history”

In January 1981, Yes met at Steve Howe’s house in Hampstead. The previous year had been a fraught one for the band: following the departure of Jon Anderson and Rick Wakeman, the three remaining members – Chris Squire, Alan White and Howe – had recruited Trevor Horn and Geoff Downes from new-wavers The Buggles. The resulting album, Drama, remains a fan favourite, but was created under extreme pressure with a US tour only months away. During the shows that followed, Horn frequently struggled to fill Anderson’s shoes. All was not well.

Horn was effectively fired after the tour, and Squire and White announced a plan to form a new project with Jimmy Page of Led Zeppelin. This left Howe and Downes holding the baby, with no appetite to continue as Yes. Within months, the remaining duo joined forces with John Wetton and Carl Palmer to form Asia, while Horn made the second Buggles album and started a production career. Then-manager Brian Lane was horrified: he’d lost Yes and the band went on to lose their record contract with Atlantic.

The few months that White and Squire spent rehearsing with Page as part of XYZ are the stuff of legend. Page, himself reeling from the death of John Bonham just months before, was initially enthusiastic and the trio pooled material, producing several demos. It didn’t take long, however, before the relationship began to fall apart, scuppered by both musical and managerial disagreements.

At a loose end once more, the pair teamed up with lyricist Peter Sinfield and recorded a Christmas single, Run With The Fox, which was released towards the end of 1981. It’s since become something of an unsung classic in the Yuletide sing-along genre.

Although XYZ never recorded an album, it’s clear that the two former Yes men had music in mind that was a little more contemporary in tone, even compared to the energetic prog of Drama. Some pieces from those rehearsals would wind up on later Yes albums: the Squire song Telephone Secrets, which never found a home with Yes, shows a band combining musical chops with commercial aspirations. This would become the template for their new band, Cinema.

Meanwhile, South African guitarist Trevor Rabin was also at something of a crossroads. Following fame in his homeland as part of Rabbitt, he had moved to the UK and released three solo albums on the Chrysalis label before a songwriting development deal with the new Geffen label led to him suddenly moving to California. However, things started to turn sour, and after a period rehearsing –ironically, with Howe and Downes’ Asia in London – he was unceremoniously dropped by Geffen. However, Rabin wasn’t short on interest.

“I started sending out demo tapes,” he remembers. “The irony is that I sent out all this material that was going to end up on 90125, like Owner Of A Lonely Heart and Changes, and they were rejected. I’ve still got the letter from Clive Davis at Arista saying, ‘While we feel your voice has Top 40 appeal, we feel your song [Owner...] is too left-field for the marketplace today.’”

Other offers came in. “There was talk of a band with Keith Emerson, Cozy Powell and Jack Bruce, but that idea didn’t move forward,” Rabin remembers. “Then Ron Fair, a fantastic A&R guy at RCA, offered me a solo deal, so it was that: the band with Keith and Jack or the possibility of a band with Chris Squire and Alan White via Phil Carson at Atlantic, who had also heard the demos.

Part of my job is being a marketing guy. A new band is difficult to sell. An established one is much easier

“In the end, Phil – who’s a pretty persuasive guy – called me up and said, ‘Come on, stop fucking around.’ So the next thing I knew, I was in a sushi restaurant in Shepherd’s Bush, west London, getting to know Chris and Alan.”

At the end of the evening, the trio went back to Squire’s house in Virginia Water in Surrey and had what Squire referred to as “the worst jam in history.” Rabin agrees: “It didn’t sound great, but it felt so right.”

Squire, Rabin and White found themselves in another development deal financed by Phil Carson personally, with the freedom to work on material at their own pace at John Henrys rehearsal studio in Islington, north London.

Carson already had a long history with Yes. As an executive at Atlantic, it was he who had convinced the label to re-sign Yes after their second album, Time And A Word, flopped in the US. He’d also introduced Yes to long-time engineer Eddie Offord and had stayed in close touch with the band, especially Chris Squire, throughout their success in the 1970s.

But the group needed a keyboard player, and both Carson and Squire saw the logic of bringing in Tony Kaye, Yes’ original keys man. Carson confirms that even at this early stage, it was in his mind that Yes should be revived while the band rehearsed. “Part of my job is being a marketing guy. A new band is difficult to sell. An established one is much easier,” he acknowledges.

So, having Kaye in the band would take the line-up closer to being Yes from day one. As a bonus, Kaye had a certain charisma, and the way he played would also suit the new band. Squire, however, had the job of selling the idea to Rabin. “Chris suggested Tony,” says Rabin. “I didn’t know him, but Chris said that he was a ‘meat and potato’ keyboard player, a real Hammond guy. He said to me: ‘I think he’ll be right for the band because you’re a little fancy!’”

They called themselves Cinema and started to rehearse material that both Rabin and Squire had originated. As rehearsals went on, Kaye also began to contribute. “We rehearsed some of my songs,” Rabin remembers, “and there was also a song called Open Your Doors, which Chris had written, that had Alan on electronic drums. We also played the song that we used as the intro to Owner... live, called Make It Easy.”

Despite the four-piece’s chemistry, there was talk of a fifth member. “During the rehearsal process, Chris mentioned bringing in a singer and suggested Trevor Horn,” Rabin recalls. “I was confused. Chris had told me that, during the shows, he started at the front of the stage, and by the third song, he was standing beside the drums. I said, ‘What for?’ Chris said, ‘He could sing, you could sing, I could sing. It might be good.’

“But I just knew him as a pop producer. He turned up to rehearsals with a guitar. I said, ‘Is that a prop, or are you going to use it?’ We just didn’t hit it off at that point at all. Within 24 hours, I told Chris that it wasn’t working for me. I loved working with Chris, Alan and Tony, but I was ready to pack it in and come home. Then, suddenly, Trevor wasn’t there, so we carried on with everything going smoothly.”

Rabin also remembers the music becoming more complex. “We were having such fun playing together, and we were introducing some interesting time signatures and some exciting chordal left-turns into the music.”

Chris said, ‘I know you and Trevor Horn won’t ever play onstage together, but how do you feel about him producing us? I said, ‘Who? The Dollar guy?’

Eventually, the band invited others to hear what they were doing. Yes fans Jon Dee and David Watkinson, both involved in the fanzine scene, were the only members of the public invited to watch the rehearsals at John Henrys

in 1982. By that time, the group had worked up some live tracks that appeared complete, yet none of these songs would appear on 90125. They played three pieces: Carry On, Make It Easy (which was then called Take It Easy) and Squire’s Open Your Doors. Between each, Kaye also worked on the keyboard introduction to what would become Hearts.

With the rehearsal period drawing to a close, the next question was who’d produce the Cinema album. Canadian Bob Ezrin, best known for his work with Alice Cooper and with Pink Floyd on The Wall, was the favourite for some time, with Queen producer Roy Thomas Baker and Rabin’s old mentor, Mutt Lange, also in the frame. Rabin remembers a long, boozy dinner with all of them. The three legendary producers got along famously, but nothing was decided and so the search continued.

In the end, Squire decided to ask Trevor Horn to take the recording on. Horn was by no means convinced. After all, he had been ousted by the band the year before, and while he bore no grudge, his wife and manager Jill Sinclair did. Furthermore, by now, he was an up-and-coming pop producer, acclaimed for his work with pop duo Dollar and on ABC’s award-winning debut, The Lexicon Of Love. Why would he get involved with a bunch of old rock stars who didn’t even have a record deal? Luckily, Horn remained a Yes fan and Squire’s charm was legendary. That charm was also needed to convince Rabin.

“Chris said, ‘I know you and Trevor Horn won’t ever play onstage together, but how do you feel about him producing us? I said, ‘Who? The Dollar guy?’ I was really apprehensive, and Tony Kaye wasn’t into the idea at all. In the end, I just decided to get my head down to make the album work.” It turned out to be the right decision, and Rabin and Horn would later form a strong bond in the studio.

With discussions continuing and with Rabin briefly back at home in Los Angeles, Horn paid a visit to hear his songs. The producer maintains that while Rabin was in the bathroom, he heard a demo of Owner Of A Lonely Heart at the end of the tape and realised it had the potential to be a massive hit.

“One inaccurate thing that keeps coming up is that Owner... was lost in some sort of bad cataloguing on my part,” says Rabin. “It’s not the case. Back when RCA wanted to sign me as a solo artist the year before, that was the song they were really hot on, and I knew that it would be a flagship track. Trevor Horn says he had to talk us into doing it, but that’s not quite true.”

While the band hadn’t rehearsed it as Cinema, Rabin always had it in mind, choosing to tackle the songs with more complex arrangements first. Horn, however, maintains that recording that potential chart-topper was the thing that convinced him to produce the album in the first place.

Recording began in London with Gary Langan as chief engineer, but Horn struggled initially. Having already dealt with new technology and relatively pliable artists, he now had to deal with experienced musicians with opinions of their own. Horn began to feel that this project was a ship beset by heavy seas.

Although their relationship was certainly improving, Horn and Rabin disagreed over the approach to recording Alan White’s drums. Robert ‘Mutt’ Lange, Rabin’s colleague from South Africa, was best known for producing AC/DC and Def Leppard with a drum style that Horn felt was wrong for such an expressive player as White. Rabin was given an opportunity to record the drums in Mutt’s style, which didn’t work, and the South African accepted defeat.

There is genuine contradiction over the ownership of Owner Of A Lonely Heart, particularly considering its massive, ongoing success. It’s mainly Rabin’s song – he wrote the chorus and the main verse melody, although a conventional middle eight was dropped. Anderson and Squire also made contributions.

Nobody at Atlantic in the USA gave a shit. They didn’t stop me doing it, but they were totally against it

Horn, however, has always claimed to have rewritten parts of the verses, saying that Jon Anderson sang the song as soon as he appeared in the studio, and was then surprised to be asked to re-record it after Horn had changed it.

However, Rabin insists that Horn had no part in the writing process and that he never should have agreed to adding his name to the credits. Rabin was understandably careful about giving up his share of the publishing, so when Jon Anderson later made some changes to the song, Phil Carson had to persuade Rabin to give up a portion of the publishing to Anderson.

Carson remembers, “I sat down with Trevor Rabin and his lovely wife Shelley, who is very astute. She asked if Trevor would make more money if we did this. I said he would. So she allowed me to give Jon the credit.”

What Horn is responsible for is the originality of the final arrangement. First, he got the band to play the song straight without any embellishments, which, according to Horn, wasn’t easy and produced a small, if brief, mutiny. Then there was the drum sound. Yes had never recorded over a click track or a drum machine. However, Horn insisted on programming the drums so that White could play over them. To his credit, White did, with the snare tuned high in the style of Stewart Copeland of The Police, whose drum sound Horn loved.

White remembered Horn gradually taking away more of his kit so that all he was left with was a hi-hat, snare and bass drum. This didn’t please everyone, with Nu Nu Whiting, White’s roadie, commenting that his drums sounded like “a pea on a barrel.”

Rabin’s guitar solo, played in fifths for a slightly off-kilter tone, was improvised in the studio, while the famous horn stabs, often misheard as orchestral, were taken from a cassette that had been transferred onto the Fairlight sampler. They had originally been used on the Malcolm McLaren album Duck Rock, which Horn had just produced. The random musical effects that make the record so unusual were played on the Fairlight by Alan White.

Recording progressed at the two Sarm studios in London, with a further session at George Martin’s Air Studios. It was there that the Grammy-winning instrumental Cinema was recorded. It was originally intended to open a long track called Time, which was never recorded in full. Due to how expensive the studio was, Horn begged Squire, famed for his terrible timekeeping, to arrive on time. In true style, he was five hours late.

At this point the band remained unsigned. Phil Carson was still financing the entire venture himself, and both Kaye and Rabin, who had homes in California, were living with him in London. “Nobody at Atlantic in the USA gave a shit,” Carson remembers of his mentorship of Cinema. “They didn’t stop me doing it, but they were totally against it.”

But there was more turbulence to come. Horn was growing gradually more dissatisfied with Kaye’s performance in the studio, and after a lengthy session trying to record the Hammond solo for Hearts, Horn snapped. Recording was paused while arguments raged, but in the end, the producer got his way, and Kaye returned to the USA.

Rabin, who remained loyal to Kaye – but who had also shown his considerable prowess when he suggested a part for Changes to Horn – was then enlisted to play most of the keyboards on the album. Horn insisted that he wasn’t trying to fire Kaye from the band, only the 90125 sessions, but understandably, Kaye took it hard and quit.

I told Chris that it sounded a bit like Yes. To which Chris said, ‘That’s why you’re here.’

Recording continued nonetheless and the album was completed. However, with Carson still financing everything, the idea of getting Jon Anderson back into the band began to gain traction. Horn and Carson were in favour, while Squire and White were resistant, although Carson insisted that the band were a much better commercial prospect with Anderson on board.

Feelers went out and an approach was formulated. Carson, who had always had a good relationship with Anderson, was the first to make contact but didn’t have a current number for the vocalist. “I got hold of Jon’s roadie, who said that Anderson was in a call box on the King’s Road in Chelsea waiting for a call from him right there and then. He gave me the number and I called Jon instead. Even though there had been a lot of bad blood, Jon expressed interest but demanded that Chris call him.” Squire took some persuading but eventually agreed.

“Chris called me and wanted me to hear some of the music he’d been making,” recalls Anderson, who was in London visiting family at the time. “We sat in Chris’ Bentley and he played me some of the songs. It was clear that Trevor Rabin could play, and I was impressed that Trevor Horn was on board as I’d liked Duck Rock. Chris played me Owner... and asked me if I’d like to come in the day after to sing it and work on the verses, as they hadn’t got them together at that point.”

Anderson obliged and went to the studio to track the vocals. “I told Chris that it sounded a bit like Yes. To which Chris said, ‘That’s why you’re here.’” After a difficult meeting with Horn, who had replaced him on Drama, Anderson agreed to come on board. “I spent two or three weeks working on the album, adding bits here and there, especially on Hearts, which I really like,” he remembers.

Despite Cinema’s updated line-up, Rabin still has a strong vocal presence on the album, particularly on Owner..., Changes and Leave It. Squire is showcased on the song he originated, It Can Happen, and also Changes, where his harmony vocals with Anderson are enough to melt any old Yes fan’s heart. Anderson says that Rabin’s vocal role “was mainly diplomatic” since Rabin had written so much of the material.

But Rabin was initially shocked to have Anderson involved and remembers telling them: “‘To rephrase what you’re saying, you want to fire me as the singer?’ I meant it semi-tongue-in- cheek. I’ve never been too proud or jealous about being the singer.” Ever the pragmatist, he saw the sense in handing the vocals over to Anderson.

All we had to play the demo to Ahmet Ertegun was this tiny mono cassette player.… The battery was pretty flat so the tape kept skipping

Now that Anderson was in the band and Owner... was in the can, Carson was desperate to get Atlantic on board too and was ready to play the track to label boss Ahmet Ertegun – but it wasn’t as easy as he hoped. “Ahmet was visiting Paris,” Carson recalls. “I grabbed a cassette of the track and sent it to the Paris office. I told Ahmet I was going to be on the next plane. So I got to his hotel and all we had to play it on was this tiny cassette player. It wasn’t even a boom box; it was a mono player. To make matters worse, the battery was pretty flat so the tape kept skipping.”

In the end, Ertegun liked what he heard, to Carson’s immense relief. “He believed what I was saying about the band’s potential, agreed to sign them; and I got all the money I’d invested back, much to the displeasure of the hierarchy at Atlantic USA.”

The final mixes for the album were completed without Tony Kaye. Cinema needed a keyboard player, and quickly, so Eddie Jobson, a virtuoso player with an excellent pedigree having been in Roxy Music, UK and, most recently, Jethro Tull, was approached. Although he stayed in the band very briefly, he appears in many of the promotional photographs at the time and is discussed in glowing terms by former Yes members, especially Anderson.

Now the album and the line-up had been finalised, there came the issue of artwork. A traditional Roger Dean cover was never considered; instead artist Garry Mouat, who had already worked with Horn and specialised in computer-generated art, was asked to produce a contemporary cover design. Such a bold image was considered appropriate, as his style fitted in with the modern production techniques the band were using sonically.

Eddie Jobson was a great player, but he wasn’t a big enough name. We needed to get Tony Kaye back

When he created the first image, the band were still called Cinema, so the grey ‘Y’ that is wrapped around the middle ellipse was originally missing its tail and was on its side, creating the ‘C’ of Cinema.

Initially the album was to have a traditional title, but in keeping with the radical, minimalist tone, the record was simply named after its catalogue number, that being 80102. However, when Carson realised that the number was not available across all territories, 90125 became the title.

With the name Cinema starting to gain traction, several other bands smelled big bucks and tried to sue – although, as Rabin noted, they never tried to sue each other. For a short while, the band were also to be called Ice, but ultimately reverting to Yes was a far simpler option.

Owner Of A Lonely Heart was the obvious lead single for the new-look band. The Storm Thorgerson-directed video was filmed in London, with Jobson included in the shoot. Once the initial promotion had finished, Jobson returned to his home in the USA to prepare for the tour. But Carson, who hadn’t been involved in the decision to fire Kaye from the recording sessions, wasn’t happy with the situation. He’d played no role in bringing in Jobson and was concerned whether the keyboard player was suitable for the band.

“Eddie was a great player, but he wasn’t a big enough name. We needed to get Tony back,” Carsons says. Kaye was approached and agreed to return. According to Jobson, he was told that not only would there now be two keyboard players but that his rig had already been designed without consulting him. He decided to move on.

Owner Of A Lonely Heart was released in late October 1983 and started a slow rise up the US charts, finally reaching the No.1 spot for two weeks in January 1984. While it only hit the top spot in the USA, the single did well in most other territories, although in the UK and Ireland it was a relatively small hit, reaching No.28 and No.30 respectively. With a rather unpleasant “maggot” scene removed and Jobson now out of the band, all his scenes were cut from Thorgerson’s video, except for a couple of glimpses.

The single’s release was followed by 90125 itself, which was a huge success. It reached No.5 in the US Billboard 200 and No.16 in the UK album chart – good for a territory in which the band were still considered to be unfashionable rock dinosaurs. Two further singles were released: Leave It, a hit in the USA, with a video by Godley and Creme, and It Can Happen, with a more conventional (if very 80s) performance video. Bold dance remixes were also created for Owner... and Leave It to appear on the 12-inch versions.

Although released on CD later in 1984, 90125 is a masterwork of sequencing for vinyl. It hits the listener hard with the big single and follows it up with the bombast of Hold On, created from a combination of sections from two Rabin demos. Despite the 80s hard-rock vibe, there are plenty of Yes-isms in this track, particularly in the complex à capella vocal passage before the final chorus.

Squire’s It Can Happen, which stems from the Cinema rehearsal period, is one song that took on a new life when Anderson became involved. The Cinema version was released on the Yesyears box set in 1991, and the contrast is remarkable with Squire’s conventional verse replaced by something a lot more surreal, building tension which is released by the Squire-sung chorus. This combination of Anderson’s lyrics and Horn’s production gives the song an extra boost that was missing from the Cinema version.

Side one ends in epic fashion with the show-stopping Changes. Rabin’s demo contains the basic verse and chorus, while the song’s proggy mallet percussion opening section was written by White and embellished by the band, the song further enhanced by Anderson’s pensive middle eight. Outside Owner..., Changes remains the best-loved track on 90125, and with good reason.

I had an accident in a swimming pool. A woman came down a slide and hit me, which led to my spleen being removed. So the tour was delayed

Side two opens with the instrumental Cinema, recorded live with Kaye still on board, before the second single, Leave It. This was the last song to be written for the album, mainly by Squire and Rabin, and is the only piece without live drums. Anderson has no writing credit, but his percussive lead vocal in the second verse contrasts beautifully with Rabin’s smoother tones in the first.

Our Song, also much rehearsed by Cinema, is made glorious by Anderson’s lead vocal over the band’s mobile arrangement. Rabin’s City Of Love, written about his accidental trip to the wrong address in Harlem in New York, is the heaviest Yes ever got, but features a powerful vocal melody and performance from Anderson. The album closes with another epic in Hearts, which developed from a keyboard idea by Kaye but features the starkest contrast between Rabin’s hard-rock style and Anderson’s free-form lyrics. It really shouldn’t work, but it does.

Anderson’s contributions are fairly easy to spot, not just via his distinctive vocals but also in his melodies and lyrics. Of the nine tracks, he manages seven writing credits, which isn’t too bad for three weeks of work. But Horn must take huge credit for balancing all these elements into something that worked across the entire album. As an exercise in banging square pegs into round holes, it’s remarkable.

It was inevitable that the band would tour in support of the album. It involved visiting the sort of venues that Yes had traditionally played in the 1970s – big arenas in the USA, with a similar schedule in Europe planned for the summer of 1984. The audio system was designed by Clair Brothers, the US-based audio company that had worked with the band in the 1970s. Cash was thrown at the visuals, too. Yes were truly back in the big time.

But there were a couple more stings in the tail. The early dates of the tour, planned for late January 1984, were postponed when Rabin suffered an unfortunate injury. “My wife and I went to Florida just before the tour – we’d decided to celebrate as we’d just heard that Owner... had gone to No.1 and that the album was Top 5,” he remembers. “I had an accident in a swimming pool. A woman came down a slide and hit me, which led to my spleen being removed. So the tour was delayed.”

He took a few weeks to recuperate, which also meant time off from practice. “In the meantime, I’d barely played the guitar, and I certainly hadn’t played any of the older Yes stuff,” he says. “I had never wanted to call the band Yes in the first place, so now I was stuck with playing some of the old Yes tunes in what I considered to be a new band. Chris reassured me, ‘You choose what you want to play.’

“On the plane to rehearse in Philadelphia, I came up with some ideas. I was concerned that my guitar style was totally different from Steve Howe’s, so Chris also said, ‘You do it your way. It’ll make the band sound like its own thing.’ That made me feel warmer, and it made the tour much easier.”

With Yes rehearsing and the setlist chosen, another problem arose. The songs were too memory-hungry for one keyboardist, so enter Casey Young: an award-winning synthesiser-player with a growing portfolio of clients and a reputation for rig creation. He had been brought in to design Kaye’s keyboard set-up so that they could play the songs from 90125 accurately. However, not only had Kaye’s presets become overloaded, but he could only play so much with the two hands at his disposal.

Squire, ever the opportunist, suggested a surprised Young. After further persuasion from Anderson, Young agreed to “run away with the circus” and join the band on tour, his rig set up underneath the stage. Young’s position below decks came about more for practical reasons than for egotistical ones, since the stage set – stark and sleek in the 1980s style – had already been designed by this point. Later in the tour, when the band played open-air shows on other people’s stages, Young played on the same level as the band, if somewhat apart.

What he actually played developed over time. Initially, he was mainly triggering vocal enhancements, such as on Changes; but when Anderson suggested he acquire a vocoder, he had parts thrown at him constantly. Anderson sometimes asked him to play new parts with a minute’s notice and he often had to double Rabin’s guitar lines, which took some concentration.

To this day, I really miss Chris and Alan; the three-piece juggernaut, as I used to call us. I just loved playing with them

Young was grateful not to have to “perform” as the other musicians were required to. Indeed, while for most of the band playing these shows was in their DNA, for Rabin it was something of a culture shock that saw him overcompensating early on in the tour. “After the first gig, I remember Nu Nu Whiting saying that I should have a satchel [like AC/DC’s Angus Young] as I’d been jumping around so much,” he says. “So I calmed down a bit after that.”

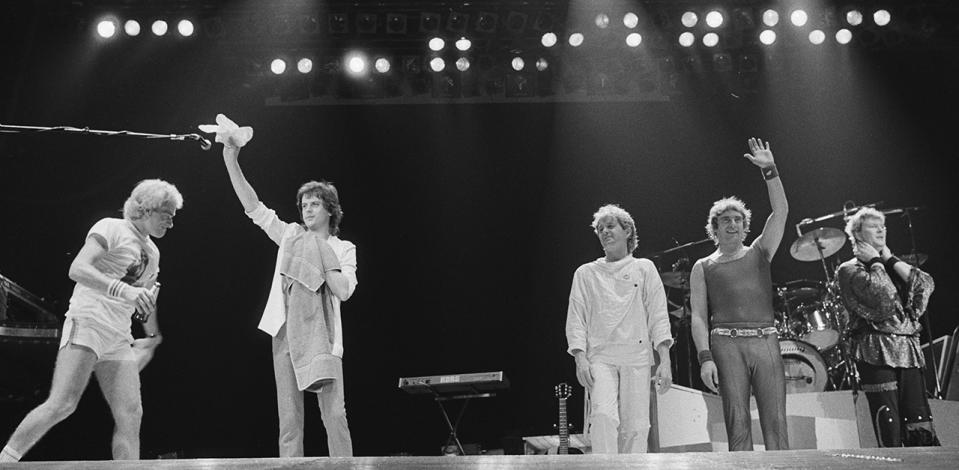

The setlist for the 9012Live tour remained fairly static, but songs moved around. The terrific Our Song wandered in and out, but the rest of the album was featured in a well-balanced show. Proceedings began with Cinema seguing into Leave It (with White playing electronic drums), followed by the more bombastic Hold On. Initially played towards the end of the set, Hearts was later switched to the first half, with the show-stopping Changes played mid-way through. Owner... and It Can Happen were performed late on, with an extended City Of Love often closing the main set. Starship Trooper was sometimes played before the inevitable encore of Roundabout.

The older material was mainly taken from 1971’s The Yes Album, which made sense since they were the pieces that Kaye had last played on with Yes, but were also the songs that best suited Rabin, who has always professed a love for Perpetual Change in particular. Only And You And I and the encore represented other areas of the band beyond Anderson and Squire’s solo sections. Squire and White’s Whitefish would include The Fish (as usual) but also segments of Tempus Fugit from Drama and Sound Chaser from Relayer, while Anderson would sing Soon.

The initial leg of the tour took in North America from February to May 1984, and after a few weeks’ break, the band reconvened in Europe for the summer, arriving in the UK in July. A further two-month jaunt around the USA and Canada up to October was followed by the first Rock In Rio at the purpose-built Citade Do Rock in Rio de Janeiro early in 1985. Almost 1.4 million people attended this 10-day festival, which saw Yes, Queen, George Benson, Rod Stewart and AC/DC each headline two nights. After further dates in Uruguay and Argentina, the tour officially came to an end in February, a year after it had started.

The shows were documented in a somewhat strange fashion; the VHS 9012Live was released later in 1985. Directed by Steven Soderbergh – who would go on to fame later in the decade as a movie director – the video captured a well-shot, if shortened, version of the shows from Edmonton, Canada, in September 1984, and combined the live performance with video effects and vintage movie footage in a way that has dated badly.

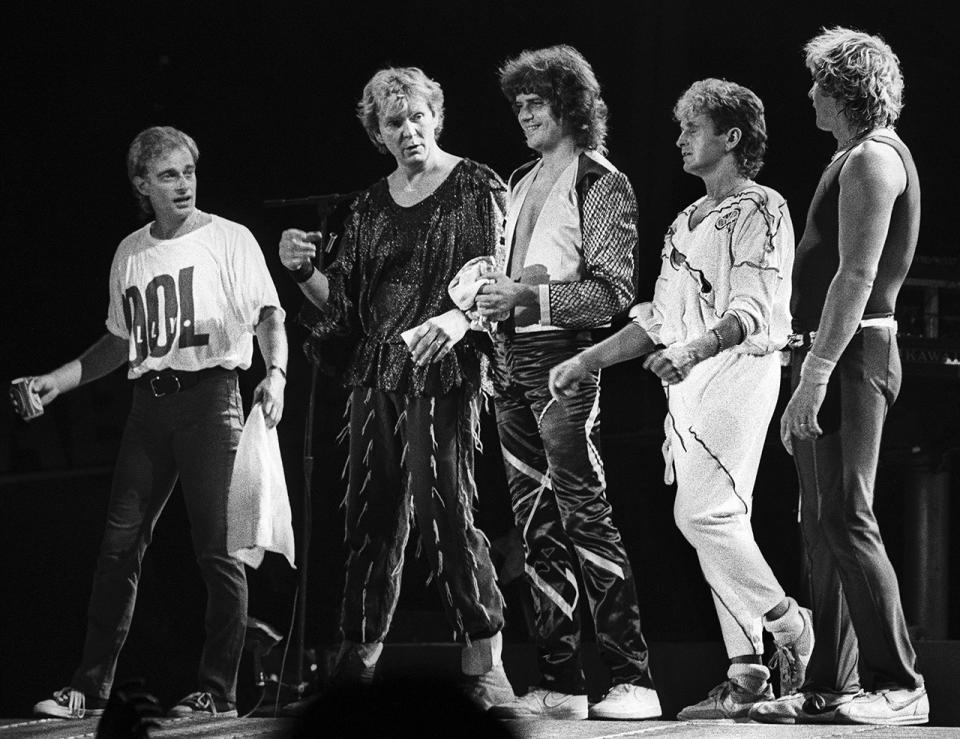

This footage, and some from another show from Dortmund earlier on the tour, gives a good example of the scale and excitement of these performances. Anderson, Squire and White’s stage personae are well represented, despite their bold attire, with Squire in particularly fine form. Kaye also oozes charisma. “On stage, he was perfect for the band,” says Rabin.

However, it’s the guitarist who steals the show, his youthful persona very different from Steve Howe’s more studious stage character. On City Of Love he’s particularly effective, and it’s obvious that playing Howe’s parts in his own style on the older songs offered him no particular difficulties.

An accompanying live LP, 9012Live: The Solos features good live versions of Hold On and Changes, and then all the solo spots from the five musicians. This was an odd choice, to put it mildly, perhaps designed as a companion piece to the VHS rather than a standalone live album in its own right. Better might have been an album that featured the songs that didn’t make it onto the video, such as Yours Is No Disgrace, Hearts or Roundabout. Or even better, a traditional double live album documenting most of the set.

Did 90125 save Yes? The answer seems clear. Rabin has always felt the album would have still done well had it been released as Cinema and without Anderson, and Carson believes Owner... was good enough to be a hit without the Yes vocalist. However, a record deal was far from certain until the very last minute.

Although Anderson’s solo career at that point had hardly set the charts alight, his work with Vangelis had produced two hit albums and two big hit singles in I Hear You Now and I’ll Find My Way Home. Anderson was a commercial bet – not just because he was the previous lead vocalist of Yes but because he was still in the public eye. Nonetheless, there’s little doubt that the fairy dust he sprinkled over the album enhanced it creatively as well as commercially. But Carson is surely the unsung hero of 90125, personally bankrolling Cinema for many months.

Without 90125 it’s possible that Yes might well have reformed eventually, like so many bands from the 1970s. However, it’s also very likely that the album’s success and the additional fans it generated, many of whom went back and discovered earlier material, gave the group a shot in the arm that remains in their immune system today.

Despite the very 1980s production techniques and a certain antipathy, even snobbery, among some fans of the 1970s era towards the 1980s version of Yes in general, the album has aged remarkably well. Like all the best music from that colourful decade, it’s the material that ensures its longevity. There isn’t one poor track on the album, and the way it’s sequenced makes it a wonderful one-sitting listen.

For Rabin, this period in his life remains one he remembers fondly: “To this day, I really miss Chris and Alan; the three-piece juggernaut, as I used to call us. I just loved playing with them.”

90125 was a product of its time, but its success is the result of a unique combination of creativity, commercial savvy and good fortune.