Karl Bartos and Kraftwerk: "The endless cycling didn’t help invent new music!"

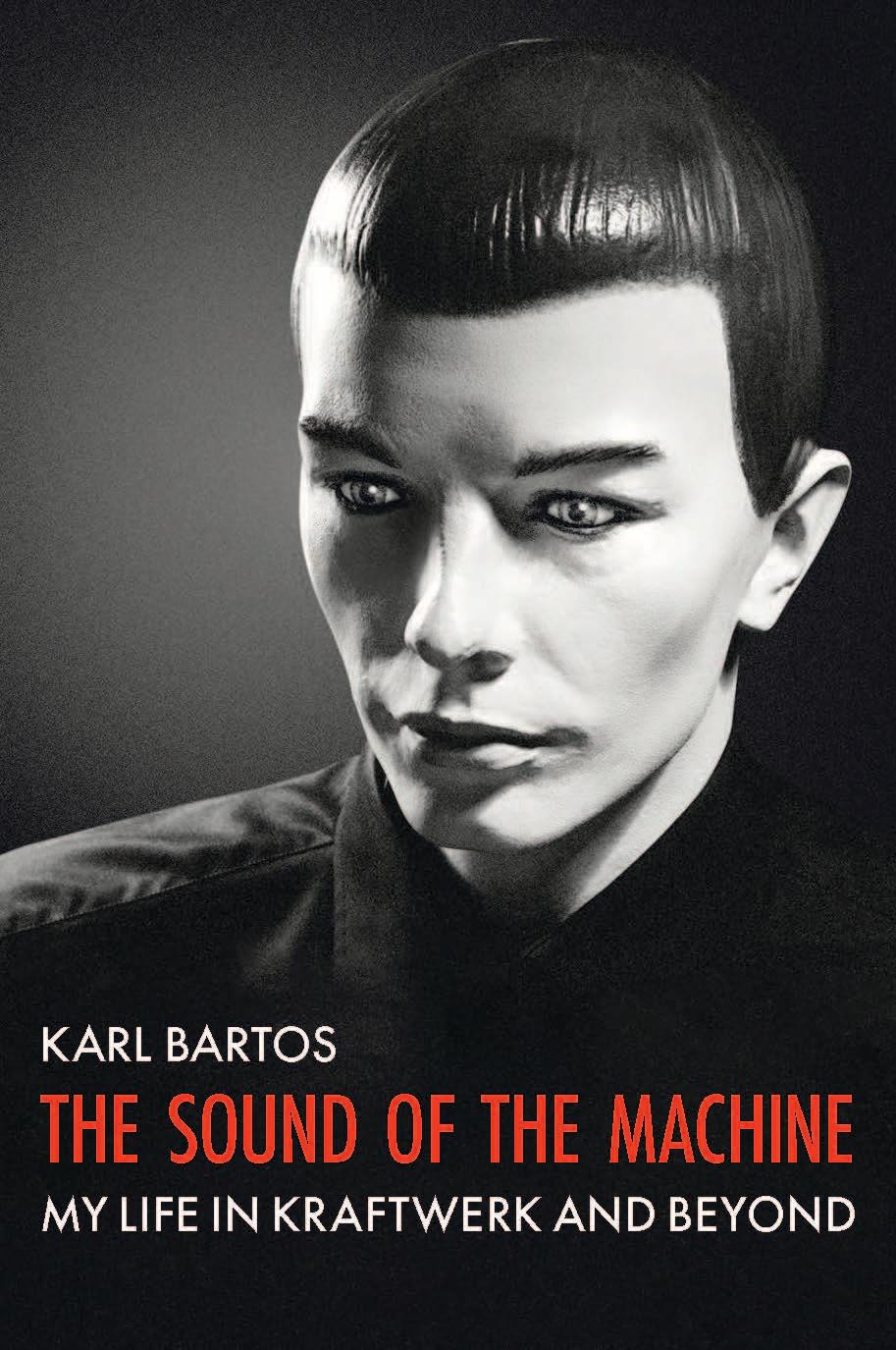

Karl Bartos might always primarily be associated with Kraftwerk, but he’s been no slouch outside of the group. As well as reliving his experiences as the second robot from left in his new book The Sound Of The Machine, Bartos explores his time as a classically trained percussionist during the 70s, his well-received post-Kraftwerk solo albums and collaborations with groups like Electronic (featuring Bernard Sumner and Johnny Marr), and his foray into academia: Bartos was a visiting professor at the Berlin University Of The Arts between 2004 and 2009, lecturing on Sound Studies and Acoustic Communication.

Born in 1952, the young Karlheinz Bartos (Kraftwerk shortened his name to ‘Karl’ to save money on lettering) was turned onto music the moment he heard the opening chord of The Beatles’ A Hard Day’s Night as a 12-year-old. As a teenager he played in bands, took acid while listening to Can and pursued a career as a classical percussionist, training at the Robert Schumann Conservatory and playing nightly for the Deutsche Oper Am Rhein. A call from Florian Schneider changed everything in 1974, when Bartos found himself hitting electronic drum pads all across America for the Autobahn tour.

Bartos became more and more irreplaceable at Kling Klang studios as Kraftwerk developed into the world’s greatest electronic pop band. They can now be regarded as a gesamtkunstwerk, though Bartos refers to the conceptual details pejoratively as a“fairytale”, a word he uses several times during our talk. Undoubtedly there are scores to settle, and a desire to wrest the narrative back in the direction of all of the band’s contributors – not least of all the Bavarian-born percussionist who co-wrote The Model, The Robots and Trans-Europe Express, to name but a few.

Ralf Hütter, founder and controller of the legacy, neither comes off well in the book nor in conversation, usually referred to simply as “my former partner”, while the current incarnation of Kraftwerk is called “the digital replacement product”. Bartos’ enthusiasm for the Kling Klang years when he, Hütter and Schneider were creating is evident, but it’s set against bitterness concerning stinginess from the keepers of the purse strings, and creatively the fact that his former band shut up shop more than 30 years ago to become a museum piece, quite literally on occasions. Unsurprisingly, Bartos and his drumming partner Wolfgang Flür have been airbrushed from the visuals.

Did your bandmate Wolfgang Flür’s 1999 account of life in Kraftwerk, I Was A Robot, influence the way you approached The Sound Of The Machine? And given that Flür ended up in court over it, were you concerned about litigation from Hütter?

No, Wolfgang chose a different approach, and no, regarding my book, I haven’t heard anything from my former partner yet. I’ll keep you informed! Naturally, journalists and interviewers have always brought up my past, but the events that took place in the Kling Klang studio were too complex to explain in just a few words. I wanted to take a few steps back and look at the bigger picture and form my opinion from a distance. During my time at the Berlin University Of The Arts, I began to realise that the Kraftwerk story, repeated over and over, is nothing more than a fairytale.

That prompted a desire in me not to leave the interpretation of my past solely to my former partner, and to tell the story of how our music came about from my own perspective. After all, I co-wrote all of Kraftwerk’s songs from The Man-Machine until I left. Today, one ex-member of the so-called classic line-up represents the digital replacement product of Kraftwerk, simply because he had the financial means to purchase the brand name. And that has nothing to do with our common ideas of trying to expand the expression of art. It is pure capitalism. But hey, he can buy the brand name, but not the lost golden trail of creativity.

You bring the Düsseldorf of the 70s to life in the book. Did the city mean a lot to you?

Looking back, I think Düsseldorf was the best place to live in Germany during the 60s and 70s. It’s a small town – almost everything is within walking distance with a strong emphasis on culture. I took it for granted and didn’t think about it at the time. Every artist, every musician, seemed to be there and I always seemed to meet Florian during the day. In the 70s, it was like heaven, but we didn’t notice! However, this Düsseldorf atmosphere has probably disappeared forever. I’d lived there for 40 years and I had to move to Hamburg. Hamburg is like a colony of England.

Hamburg has thrown up a number of opportunities, including a record deal with the Bureau B label. Your 2013 album Off The Record was brilliantly received, and I’m wondering if you feel it’s a consolidation with your past?

Off The Record is the auditory forerunner of my autobiography. My next album, which should be out next year by the way, will also appear on the Bureau B label.

With Kraftwerk, I experienced one of the most fascinating encounters of creativity in my life. When I think about it, I brought the tradition, life and spiritual power of classical music to that environment. Playing the immortal music of the great composers was part of my everyday life. My partners at the time had no experience with music in other contexts. I think it makes a difference whether you buy a record by Richard Wagner, Franz Schubert or Karlheinz Stockhausen and talk cryptically and in a blur about it in interviews, or you play these works in concert as part of the musical tradition.

Were many of the ideas for Off The Record rejected ideas from your time with Kraftwerk?

I came up with some ideas like International Velvet somewhere during the 1981 tour, and wrote them down in my sketchbook. But my ideas and comments always found their place in the studio. Music is my language and my mirror. It was different on the business level, though. I studied music and not business administration. The problem was: the creative process was a communal joy and effort, but recognition and profits weren’t. That did not work in the long run.

We decided way too early to record some ideas for Electric Café [now known by its working title Techno Pop], and then we didn’t play them live in the studio or on stage and combine them with other ideas. That’s when one of us started getting into extreme sports, but his endless cycling didn’t help invent new music. A tired brain makes bad decisions. It was probably more of an obsessive-compulsive disorder to fill the inner emptiness.

Although my partners lived bohemian lives, they raised Kraftwerk like a capitalist corporation. I come from a different background, and at the Robert Schumann Conservatory and the opera you don’t learn capitalistic thinking. Exploiting other people makes you feel lonely, I guess. Maybe it would have helped us if we had been fair to each other. And then my former partner became a travelling salesman of nostalgia.

In the book, you go back to your Alpine roots in Bavaria (Bartos’ family relocated to Düsseldorf when he was two). What was that like?

I went back to Berchtesgaden, where I was born, because I wanted to start it there. It played its part in the darkest chapter in German history. It’s such a beautiful place and you just can’t understand how it all happened. When I returned, I went very often to the Kehlsteinhaus at the head of the mountain – or The Eagle’s Nest in English. If you’re there, you’re on top of the clouds. It’s like a perspective you get from being in an aeroplane. The Kehlsteinhaus looks exactly the same except the swastika has been removed.

It’s often noted retrospectively that German kosmische groups were remaking the culture as a reaction to what had come before. Was there a sense that this was your mission?

When I started in Kraftwerk, one of my typical days looked like this: in the morning we listened to and discussed Claudio Monteverdi’s 1607 opera L’Orfeo in music history, then had lectures on harmony and counterpoint. Ear training and piano lessons followed. Then we would perhaps rehearse a few bars on the vibraphone for a concert of new music over the weekend, and in the evening we’d go to the Opera House for a performance of Benjamin Britten’s 1973 score for Death In Venice. The next day I was rehearsing music from Karlheinz Stockhausen. I didn’t really have the feeling that I was living in a cultural vacuum.

Was there a sense of a scene among the so-called ‘krautrock’ bands or was that mostly a product of the British music press of the time?

The ‘krautrock’ scene was more underground then. And my previous partners were rather shy and largely avoided contact with other musicians. I think it was the elite phenomenon. From the start, Ralf and Florian had this aura of money, private school, boarding school – later on, big cars, constant vacations, flying to New York on Concorde, the surreal Synclavier period [Electric Café], etc. For my partners, success was the focus, and for me, it was always the music. I felt more connected to classical music, the classical avant-garde and jazz, and considered myself – and still see myself – as a very small part of the living music culture. I was never a part of that krautrock thing. Although I really like the taste of sauerkraut!

If we go right back to the beginning, you were first turned onto music by the opening chord from A Hard Day’s Night. Have you ever deconstructed that famous Beatles’ chord?

The A Hard Day’s Night opening chord is wonderfully explained on the net. It still sounds magical to me. It’s a bit like in that song Yesterday Once More by the Carpenters, but of course I’ll never have the same feeling I had as a little boy again. Back then I wanted to feel what The Beatles sounded like and life seemed endless before me.

My good friend Johnny Marr once told me the story of when he lived in London and Paul McCartney called him and said: “Do you want to come over?” So he went over to Paul’s and they played I Saw Her Standing There together and he was singing the John Lennon part. I envy him for this. I couldn’t have done it. I would have had a heart attack!

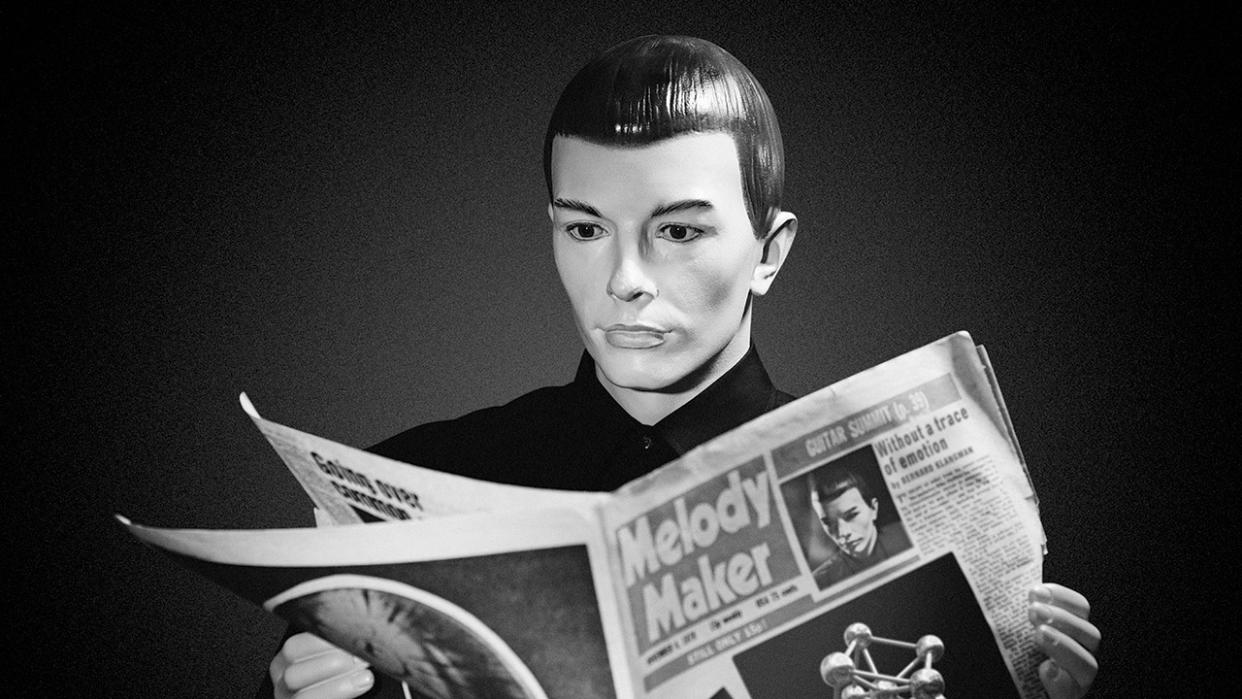

You’ve been an influence on nearly everyone in modern music, but are you influenced by musicians who were influenced by you – namely Bernard Sumner from New Order and The Smiths’ Johnny Marr – on songs like Without A Trace Of Emotion?

Songs talk to each other and although Without A Trace Of Emotion is self-referential, it seems to converse with the songs of Bernard and Johnny. I would have given anything to play live with Johnny and Bernard [in Electronic]. The other day I was chatting with Johnny on FaceTime. I read him my latest lyrics. Suddenly he picked up his guitar and played a rhythm to my poem that he felt was right. The thing is, musicians on Johnny’s level live and breathe music, and there’s a consensus that making music is all about listening, feeling, playing and thinking.

We just spoke about McCartney and I got a sense from reading The Sound Of The Machine that popular narratives might change – such as when Barry Miles’ Many Years From Now debunked the perception of John Lennon as the avant-garde Beatle (now we know that McCartney was the Stockhausen fan). This book makes a firm case for your important role in the creation of Kraftwerk’s music, doesn’t it?

Well, that’s why I had to write a book. There was a reason I had to write a book, because the narrative for 40 years is still going on. It’s just a fairytale. It wasn’t about the trademark, the money or the deep pockets of my former partners. It wasn’t just about the machines. It was three people in a room, improvising music. It was kids playing like kids, getting in the so-called flow for almost five years. It didn’t stop after the ’81 tour, it went on for another two years, maybe. But then it stopped when the computers came in, unfortunately, in the name of so-called progress. Nowadays, I think innovation and progress are synonyms, but they aren’t really. Is a machine gun progress? Or the atomic bomb? As they became more involved with the digital world, the more it became a business model.

You talk of your former partners as being entrepreneurs and there’s an image that won’t leave me where Ralf Hütter is sitting reading Le Monde in a pair of bicycle shorts while he massages oil into his calves…

[Laughs] I had to write that because it was true. It’s a real situation shortly before I left the band. And I had to leave the band, of course. Kraftwerk was the act of creation, it was a communal effort and a communal joy, but recognition and profits were privatised like they are in industry. In the beginning, we were a group of artists, but it ended up being a capitalist environment. Always money and always new machines, and new innovative machines are there to produce better music, but it’s not true. The more new machines came into the studio, the less music we made. They invented this procedure by which you copy and paste analogue songs into digital media and repeat it over and over again, but if you tidy up art, the result of it is not a new piece of art.

How important was the advent of the Synthanorma sequencer to Kraftwerk in the mid-70s?

Yeah, it was, but it’s not really an invention of the 70s. The musical box was invented several hundred years ago! They were talking about automatic music in antiquity, can you believe it? During the classical period or even later in the 19th century, composers were fascinated by this idea of artificial music. Because you couldn’t record music at the time, it was impossible. So it was always a fascination.

I’m interested in the progressive electronic music that was around in the 70s, and how it was perceived by you and by Kraftwerk. Were you aware of what was going on with artists like Tangerine Dream, Klaus Schulze and Vangelis?

At that time, Stravinsky’s Sacre Du Printemps was on the repertoire of the Deutsche Oper Am Rhein. In truth, I was working. I was studying music. I remember after the Autobahn tour, we played Benjamin’s Britten’s Death In Venice at the opera. There were many drummers playing, at least 10. I had a small part on the microphone to play. Then Ralf picked me up in his car and we went into the studio where The Rite Of Spring was playing. I was filled up with the sound, the sound was inside me. Stockhausen was a perfect match, too.

You worked out that you were in the orchestra pit playing Prokofiev’s The Tale Of The Stone Flower the night the Sex Pistols first played Lesser Free Trade Hall, didn’t you?

I was talking with Bernard Sumner about this moment and he told me how influential they became. And at the time, I was inspired by Stravinsky, and pop music was resting in my soul, too. You can’t get rid of Bob Dylan and The Beatles and the Black music from America, and all the music from London, as it’s all too close. That’s the history of music: America was invaded by the Europeans, who brought their music, and it mixed with the music of Afro-American slaves. And from that came blues, country and western and jazz, of course.

You write a fair bit about Pink Floyd in the book. Did Kraftwerk see them as rivals?

Not really. Pink Floyd are a phenomenon. They were in a different league. But our potential with the classic line-up was already far greater than what the digital substitute of the former Kraftwerk has achieved today. For true artistic success, my ex-partners would have had to overcome their egoism, because now it’s becoming clear that it was not the machines that wrote our songs. It wasn’t the brand name, either. It was us, the people. What a surprise!

In my autobiography, I talk about the touchpoints of Pink Floyd. From my point of view, Richard Wright’s setup and his way of playing the keyboard was a great template for my former partner. Ray Manzarek was also an important figure. If you want to delve deeper, you should analyse Pink Floyd’s work.

I would say that On The Run, Astronomy Domine and Echoes were more than an inspiration.

Perhaps you’re being a little modest. Kraftwerk are one of the most influential groups of the past 60 years, surely?

The invention of Kraftwerk was really the aestheticisation of technology. We didn’t invent the Eiffel Tower, we just showed how it was built; you can see the steel statics and nothing is hidden. I would say one of the most important, overlooked things about Kraftwerk is that we didn’t invent the geography, or the mathematics, or the music or whatever; the grammar was invented before, by somebody else, but if you put the rhythms created by a jazz drummer or a pop drummer into the electronic environment, something changes. For instance, let me tell you about how I came up with the beat for Numbers unconsciously.

When I was growing up, I was listening to the songs my sister was playing on her stereo player. She was in love with Elvis Presley and Cliff Richard too for some reason [laughs]. Cliff had a really good band, The Shadows, and a good drummer, Brian Bennett. He did the intro to this wonderful song called Do You Want To Dance?, originally a Bobby Freeman song. So my subconscious brain from when I was a kid transferred this sequence by an English drummer into the song Numbers, because that’s how music works.

This article orignally appeared in issue 133 of Prog Magazine.