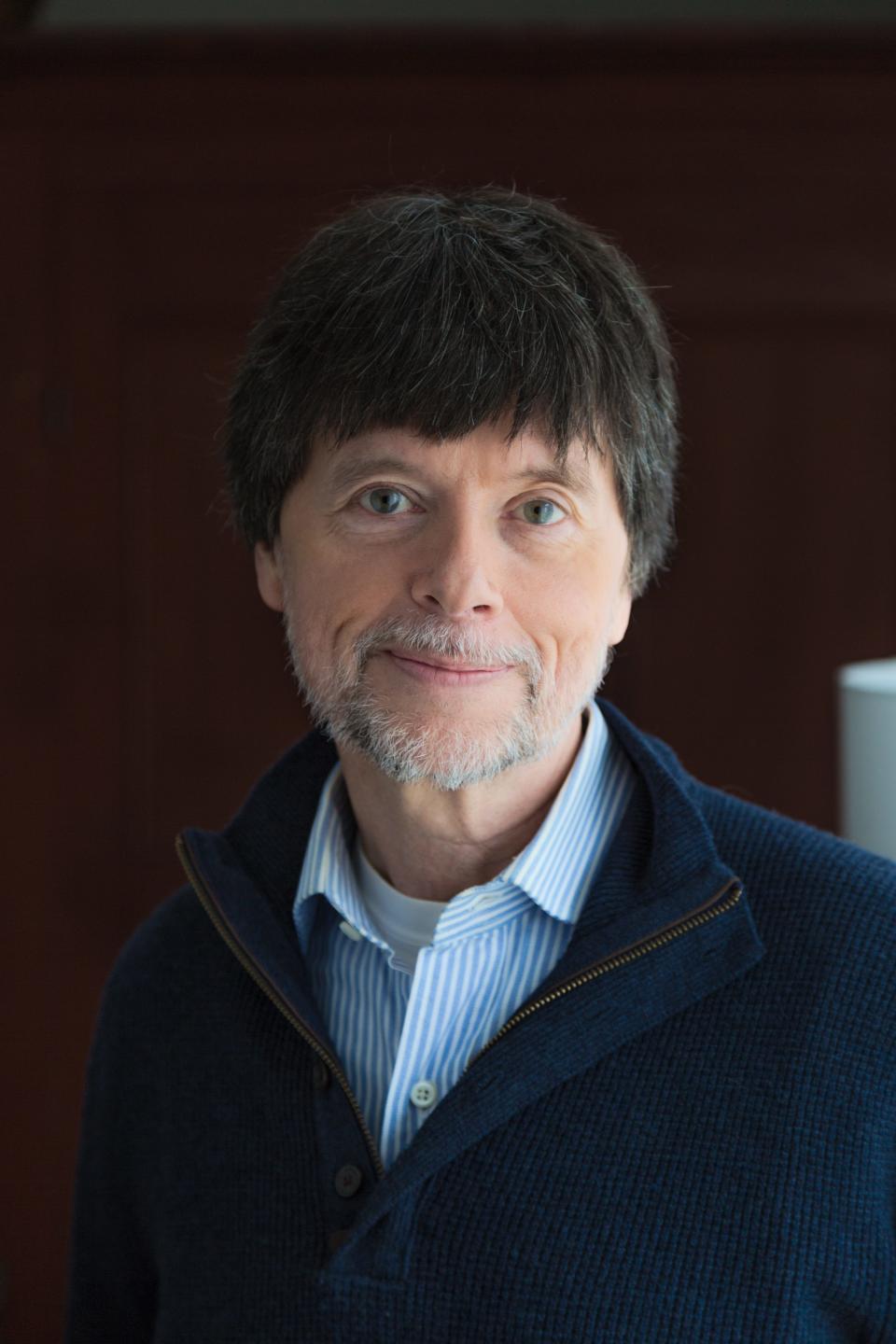

Ken Burns explores the virtues, vices of Benjamin Franklin in his latest PBS documentary

Ken Burns has been making the same film over and over again for 40 years.

His subjects may span centuries and cross cultural divides, but the filmmaker says each of his nearly 40 documentaries ponders the same deceptively simple question: “Who are we? Who are the strange and complicated people who like to call themselves Americans?”

Most people would buckle under the weight of such questions. Burns, however, has built an Oscar-nominated and Emmy-winning filmography working through them, one person, event and American hallmark at a time.

Last year, he debuted PBS films about Ernest Hemingway and Muhammad Ali. In 2019, he traced the origins of country music and in 2017 unfurled “The Vietnam War,” which took a decade to produce.

But his latest effort travels further back in history than he’s gone in more than 20 years, since 1997’s “Thomas Jefferson.” He’s returning to PBS with “Benjamin Franklin,” a two-part film (Monday and Tuesday, 8 EDT/PDT; streaming on pbs.org) about the man he decisively calls the “most compelling American character of the 18th century.”

More: There is no national day to honor hometowns. So Ken Burns is asking for your help.

“All of our attention in this period quite correctly is on a Jefferson, on a Washington, on an Adams, on a Madison, and lately on a Hamilton,” Burns says. “But Franklin is on the $100 bill because he’s about striving to lift yourself up. His story is so fundamentally American in lots of really good and really bad ways that it is, to me, irresistible.”

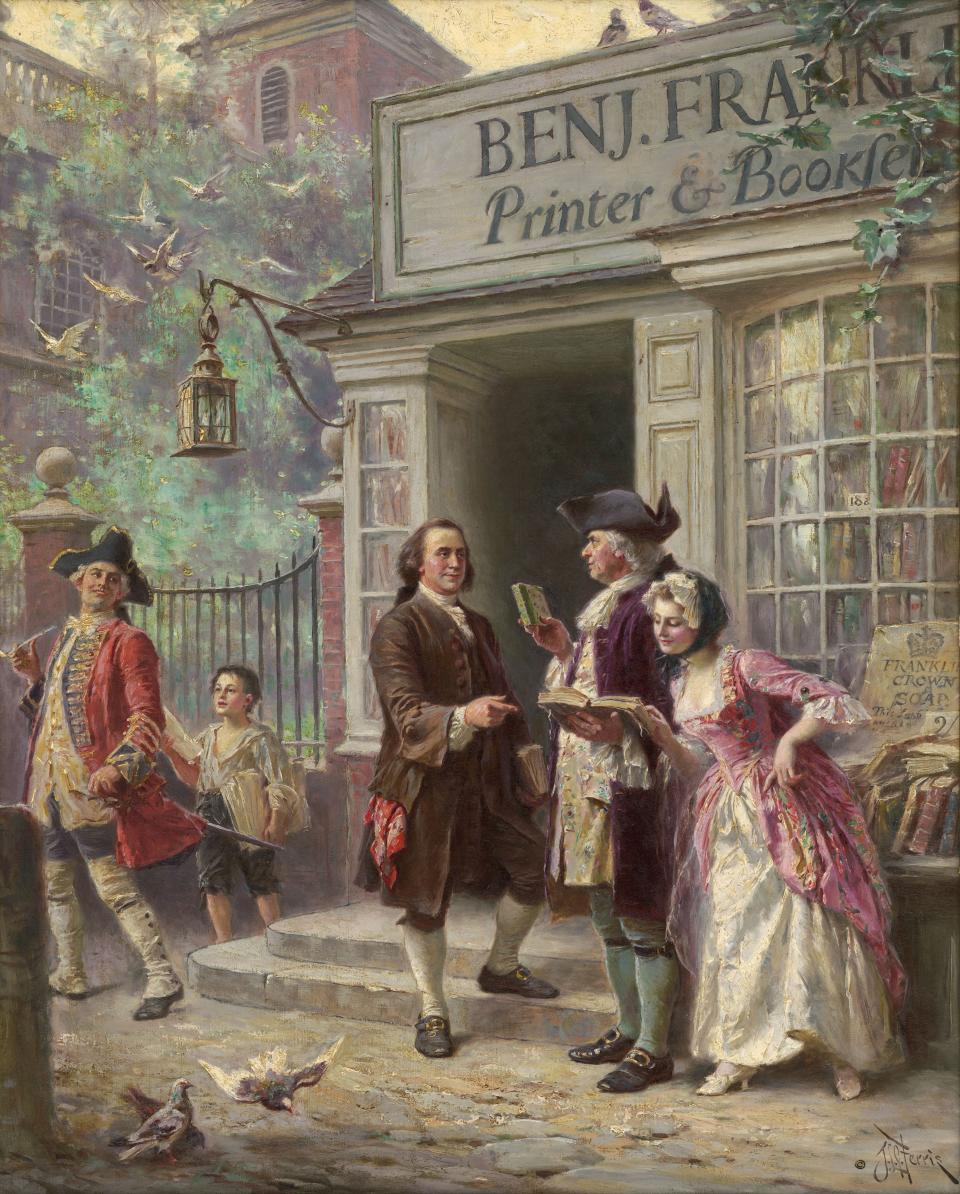

An influential printer by trade, a prolific inventor by hobby and a definitive politician by compromise, Franklin posed an enticing challenge for Burns, who famously immerses viewers in photos and film footage that preserve his given subjects.

Franklin predates such inventions, leaving Burns and his team to curate a delicate dance of paintings, animations, written sources and the commanding voice of Mandy Patinkin as the Founding Father to interrogate America’s collective memory of a complicated man.

“We can understand Franklin Roosevelt or Muhammad Ali a little better because we feel like we can reach out and touch them,” Burns says. “The challenge here was to make someone from the 18th century come alive in a way that has dimension, has flaws.”

Franklin printed some of the most influential papers of all time, pioneered our understanding of electricity, wrote extensively with a remarkably dry wit, negotiated France’s Hail Mary involvement in the American Revolution and guided his fellow Founding Fathers in creating a more perfect union than the one he knew.

But he was also a negligent husband, an estranged father and a slave owner and eventual abolitionist who was instrumental in writing the Constitution, particularly the concession that gave Southern states the authority to count enslaved people as three-fifths of a person.

He was imperfect, and that's what appealed to Burns.

“We don’t live in a melodramatic world, and we don’t have a melodramatic history,” he says. “We have, as I.F. Stone said, a tragic history, which means these contradictions, the virtue and the vice, are included within people. The tragedy of human existence is more interesting to me than 100 melodramas in which you’ve isolated some superficially ‘perfect’ hero who never was.”

An essential component of breathing life into Franklin’s complex legacy was finding his voice through Patinkin, whom Burns effusively praises for capturing the spirit of Franklin.

He “brought such incredible life force to Franklin’s writings; I don’t have any other way to say it,” Burns says. “He is a beautiful human being, and he gave us every ounce of his talent to will to life someone who has been dead for well over 200 years. That is such an extraordinary gift.”

Joining Patinkin are Josh Lucas as Franklin’s Loyalist son, William; Liam Neeson as a member of the House of Commons; and Paul Giamatti, who reprises his Emmy-winning role as John Adams, which he played in HBO's 2008 miniseries. Frequent Burns collaborator Peter Coyote returns as narrator.

Burns’ long-awaited return to the 18th century also serves as an opening act of sorts for an even more exhaustive project on the horizon.

He is now years into work on “The American Revolution,” a five-part chronicle of the foundational war that will arrive just in time for its 250th anniversary.

“It won’t be out until 2025, but I have to say that feels like tomorrow,” Burns says.

“The Revolution has everything; it is pretty much the challenge of ‘Benjamin Franklin’ multiplied by three or four because of its length. But like Franklin, it has such a new history, and yet the superficial story is baked into our narrative of ourselves. We aren’t going to throw that away but we’re going to make it more complicated, as it should be.”

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Ken Burns: Why Benjamin Franklin is a fascinating documentary subject