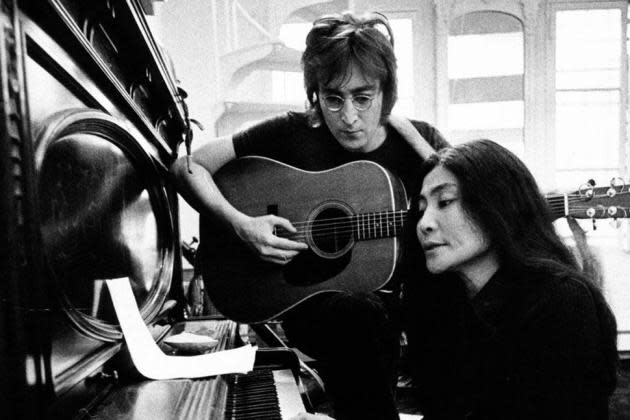

Kevin Macdonald On Diving Into John Lennon’s Archive For Venice Doc ‘One To One: John & Yoko’ & The Musician’s Connection To Politics Today: “We’ve Talked About The Same Things For 50 Years”

1970s New York.

Andy Warhol, Susan Sontag, Studio 54, John Lennon and Yoko Ono.

More from Deadline

It’s a period that has been explored to death, with countless works on the ‘scene’ across the city. Is there really anything fresh or engaging to be said about that time or its main protagonists? Scottish filmmaker Kevin Macdonald offers an interesting answer with his new feature documentary One To One: John & Yoko, which debuts tomorrow at the Venice Film Festival.

Set in New York in 1972, the ambitious and formally experimental film explores the time through the musical, personal, artistic, social, and political worlds of John Lennon and Yoko Ono. At the core of the film is the little-known One to One charity concert for special needs children, John Lennon’s only full-length concert between the final Beatles gig in 1966 and his death. The film includes a collection of previously unseen Lennon archives, including personal phone calls, home movies filmed by John and Yoko as well as restored and remastered footage from the One to One concert with remixed audio overseen by their son, Sean Ono Lennon.

Macdonald’s unique approach to the material provides viewers with an intimate look into the legendary couple’s lives but also creates a powerful bridge between the violent turbulence of 1970s America and our social and political climate today.

RELATED: Venice Film Festival 2024: All Of Deadline’s Movie Reviews

Below, Macdonald speaks to us about diving into the archives of the Lennon estate, visiting John and Yoko’s now-demolished apartment on Bank Street in Manhattan, and what Sean Ono Lennon said after seeing the film.

The Venice Film Festival runs until September 7.

DEADLINE: This film was announced a few years back. But where did the idea come from to focus on this one concert John and Yoko gave?

KEVIN MACDONALD: I was approached by Peter Worsley, the producer who has been working with Mercury Studios, which is part of Universal Music. They have the Lennon catalog and own the rights to the One To One concert. Sean Lennon and various other people had been trying to rescue the sound of the concert. The sound had been so badly recorded by Phil Spector. He was probably completely drunk at the time. The recording was really bad. That’s why it’s not better known. It came out once in 1986 on VHS but that was it. So with modern sound technology, they managed to pull out the audio and remix it, at which point they came to me and asked if I had an idea about how they could make a film about this.

RELATED: Netflix Takes U.S. Rights To Pablo Larraín’s ‘Maria’ Starring Angelina Jolie

I was a Beatles fan and was particularly fond of John, so I was never going to say no. But I thought there’s been so many films about The Beatles and Lennon, how do you say something fresh? I was doing a bit of research, and I came across these quotes where John talked about when he went to America, all he did for the first couple of years was watch TV. It’s the quote that starts the film. So I thought it might be interesting to replicate his experience in the early days of being in America, trying to understand this country through how it presents itself on television.

DEADLINE: There are so many gems from the archives in this like John on the phone with his manager, pitching these wild ideas…

MACDONALD: And the manager is always totally against them. And then as soon as John pushes him, he says it’s a great idea. That’s every artist-manager relationship that ever existed. Those calls were a real treat to find. They weren’t one of the first things I heard. I was given this drive with all the Lennon home movies and interviews. All the stuff the estate had. It was just an amazing gold mine of unseen things. All shards, none of them complete. They don’t tell the story, but there were moments. A few months later, I was called up by Simon Hilton, who was the sort of liaison with the estate. He said we’ve just found this box of audiotapes. Apparently, for a while, Yoko wanted to record all their phone calls. The estate hadn’t even listened to them.

DEADLINE: Where does the estate keep all of these things?

MACDONALD: Well because Yoko was an artist even back then, in the Sixties, she carried the tradition of collecting all the pieces of her artistic life. You meet a lot of visual artists now who keep everything archived in boxes with tissue paper. She already had that kind of attitude. So she kept a lot of stuff. I don’t think John was necessarily a collective person, but she was. So things like the bed they had in New York are still there. That was where the idea came from to rebuild the apartment where they were watching television. In the original ending, which I sort of regret taking out, I went out to New York and visited their old apartment on Bank Street. Lo and behold, it was being knocked down and turned into like a $70 million house with a triple basement and a pool and all that shit. So the guy let me in there and I filmed them destroying where their bedroom had been. That was originally the end of the film.

DEADLINE: Wow, do you think you’ll ever release that footage?

MACDONALD: I’m sure we’ll put it out somewhere.

DEADLINE: The thing I’ve always admired about The Beatles and John is how avant garde they really were. And this film really taps into that energy.

MACDONALD: Yeah, they were. That’s why almost every musical form except rap, I would say, The Beatles were sort of there first. People also give Yoko such a hard time, but I think she was truly avant garde. She really was a member of the New York art scene. One of the things I was pleased about when Sean Lennon finally saw the film is that he said “This is the first film that’s truly captured who my mother was as an artist and a person.”

DEADLINE: I’ve always thought John was erratic in his beliefs at this time in his life. He was still quite immature and trying to figure out who he was and what he believed in. That’s why he latches on to so many things. And that’s pretty clear in this film.

MACDONALD: I think that’s right. It’s amazing to think he was 31/32 when the film begins. The film covers 18 months from when they moved into Bank Street until they moved into the Dakota. It’s a story about how this concert came to be and this little-known period of their lives. I think you also see someone who is almost in trauma from the experience of The Beatles. He’s running away from that and trying to figure out who he is. Nobody else had done what The Beatles achieved except for Elvis, who’d made a total mess of it. And there was so much unpleasantness, particularly around Yoko in Britain. A lot of that was racism. The way she was treated in Britain was pretty appalling. So they were escaping from that and trying to figure out who they were and what they wanted to do.

DEADLINE: Yeah, it’s funny, the story of John and Yoko in New York is really a story about Britain. And, in some ways, mirrors the U.S. and UK today.

MACDONALD: That’s true. Once we started doing research on what he would have been watching on TV, we found that all the news clips and shows were incredibly similar to things today. Instead of people protesting about Gaza on the campus, they’re protesting about the Vietnam War. It’s America today, still unable to come to terms with its racial issues. You have George Wallace, a populist politician very much like Trump, saying stuff like “You’re not safe in the big cities in this country” and then he gets shot. I couldn’t believe it then when Trump was also shot. We always think we’re the first generation to worry about the environment. But back then, Nixon started the Environmental Protection Agency, which was the one good thing he did in office. So we’ve depressingly talked about the same f*cking things for about 50 years, and we still haven’t figured them out.

DEADLINE: One omission from the doc I thought was interesting is Paul McCartney. Around that time, he and John were going back and forth with diss tracks, right?

MACDONALD: There’s no real omission in the sense that I wanted to leave things out. The approach for this film was to use whatever existed. So I can’t be accused of leaving anything out because I just didn’t have everything, which was a refreshing position to start from. I hope the film can reach a wide audience and I hope people connect to it. But I’m aware that it’s a structurally unusual film. So I don’t know what the wider audience will think. But I do believe it’s entertaining and engaging because John and Yoko are very entertaining and engaging.

DEADLINE: You made this doc with Plan B. What is it like working with those guys?

MACDONALD: I’ve known Jeremy and Dede for 20 years. We were friends and then recently decided to set up this documentary joint venture to try and do in documentary what they’ve been doing in fiction films and and TV series. Which is to try and make artistic and ambitious work that, despite what the industry might think, will connect to an audience. What I really admire about them is that they’ve stuck to their guns and it’s paid huge dividends over the years. That’s obviously partly because of Brad who has enabled that ethos and supported the work.

DEADLINE: You’ve had quite a diverse and unique career compared to most British directors. Why do you think you’ve managed to work so freely for so long?

MACDONALD: I’m very flexible and curious. I come from a documentary background so often the subjects, even in fiction, come from a political place. Take The Mauritanian, for example. That film gets done thanks to the support of a lot of big stars and nobody is really making any money. I’m not sure that many other filmmakers want to enter into that terrain. They want to make the kind of films that they want to make, which may require bigger budgets and personal stories. I’m not really a personal filmmaker in that way. I’m just very curious about the world and how I want to make lots of different kinds of films.

Best of Deadline

Sign up for Deadline's Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.