'Kids' at 25: How a shocking indie teen drama scared '90s teens into practicing safe sex

We were psyched. Kids was coming to one of our local arthouses, and even only as 15- and 16-year-old teens, we had heard “the buzz.” It was right there at the top of the poster, with Rolling Stone’s Peter Travers declaring it “the real movie event of the summer.” And it was controversial as hell.

Written by 19-year-old skateboarder Harmony Korine and directed by Larry Clark, the docu-style drama that had debuted at the Sundance Film Festival some six months earlier was the supposedly real deal, an authentic portrayal of how many young folks actually acted in 1995. This wasn’t the unrelatable “cruising” of American Graffiti our parents showed us, or the contemporary fairy tales from John Hughes our old siblings and cousins loved. It wasn’t a sanitized depiction of American youth like other teen movies being released that year, films like Clueless (a glossy look at the ultra-rich), Empire Records (a harmless hodgepodge of coming-of-age clichés) or Dangerous Minds (an examination of inner-city strife, albeit told through the POV of Michelle Pfeiffer’s white savior).

It promised to be grittier and edgier than Dazed and Confused, the ‘70s-set stoner flick we were still quoting two years later and that, despite a two-decade difference in time, we still related to on certain levels. It promised to show kids skating, shoplifting, rabble-rousing, drinking, smoking and let’s face it — most intriguing of all to a group of four teenage dudes, having all kinds of sex. We were drinking and smoking at the time, and some of us were even lucky enough to be having a little bit of sex.

It was set in the concrete jungle of Manhattan, which to teens raised in the city — albeit a much smaller city, on the opposite side of the state, in Buffalo — was the epitome of cool. They could get anywhere by subway. We had a single subway line.

The MPAA had initially decided the movie was too real, assigning the dreaded, box office kiss of death NC-17 rating. Clark successfully protested, and Kids was ultimately released ‘unrated,’ meaning we didn’t have to borrow older friends’ IDs or pay for a PG-13 movie starting around the same time and sneak into the theater — tricks we employed for other films around that time like Clerks and Showgirls. Though, admittedly, the adrenaline rush of pulling one over on “The Man” was part of the fun.

Sitting down for Kids was a rush in itself. And then the movie started.

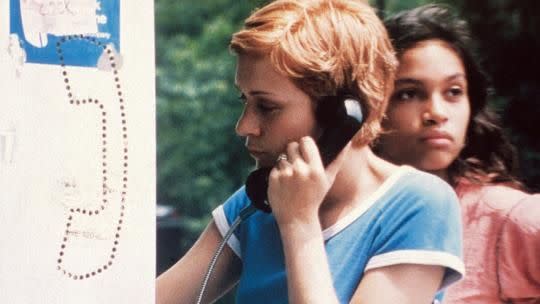

The film follows a day in the lives of a loosely connected group of New York teens, focusing primarily on the sexual conquests of 16-year-old Telly (Leo Fitzpatrick). In the opening moments of the film, Telly persuades a 12-year-old virgin to sleep with him. Across town, Jennie and Ruby (Chlo? Sevigny and Rosario Dawson, respectively, both in their film debuts) get results to STD tests. While Ruby is clean, Jennie tests positive for HIV despite having only had one partner, Telly. Jennie then embarks on a desperate quest to track down Telly before he can transmit the disease further. She fails, ultimately finding him already in bed with another virgin. After Jennie passes out from the effects of a pill a raver had popped into her mouth, she’s raped by Telly’s best friend Casper (Justin Pierce), who likely contracts HIV in the process.

Perhaps because of our hedonistic expectations, there were certain aspects of the film we relished in, even quoted incessantly, part of any moviegoing ritual at the time. The fact that the film’s 16-year-old “hero” Telly called himself “the virgin surgeon” was to our not-so-fully formed minds, hilarious. We mimicked the drunken bathtub ballad of “Casper the Dopest Ghost,” which, looking back, is one of the darkest moments in a devastatingly dark film, and willfully ignores that the same character would later become a rapist.

But more than anything, deep down inside, Kids scared the living daylights out of us, especially the older we got.

The HIV/AIDS pandemic was raging in the mid-‘90s, and still there was no subway PSA banner or health class VHS tape that could’ve come close to carrying as effective a safe sex messaging as Kids did.

We weren’t nearly as unruly or plain awful as Telly and Casper. We didn’t jump people in the park, hurl obscenities at gay couples or assault girls. But with Kids, Clark had essentially executed a masterful sleight of hand, luring us in with the promise of teenage debauchery among Manhattanites we were prepared to idolize before smacking us in the faces with a deeply visceral cautionary tale that demonstrates how, especially in the case of Jennie, the story’s most tragic character, one bad decision could potentially be a death sentence.

It resonated with us as we finished high school, went off to college, and became professional adults. And that was likely by design.

“The AIDS thing was like Jaws,” Korine told Rolling Stone for a 2015 oral history on the film. “It was a device that propelled it. We didn’t know anything about this disease other than that we didn’t want to get it.”

“Kids reconfigured the perception of AIDS at the peak of its epidemic, suggesting through the film’s bone-chilling rape scene that HIV could be contracted through heterosexual sex,” Dazed magazine’s Trey Taylor wrote in a separate 2015 oral history of the film. “Whether this was at the forefront of Clark and writer Harmony Korine’s minds at the time is moot. Poking narrative convention in the eye, the movie levels with its audience.”

Indeed, Clark, especially, caught heat for his sordid depiction of American teens having sex, with accusations of child pornography leveled at him. (It certainly didn’t help the photographer-turned-filmmaker’s cause that youth sex became a hallmark of his oeuvre between Kids and his later films.)

Others doubted the effectiveness of Kids. “The notion that some teenager somewhere will be taught to practice safe sex by seeing Kids is absurd,” wrote Jonah Goldberg, clearly an adult at the time, in Commentary magazine upon the film’s release.

Kids, at least for a group of four teenage guys from Buffalo, was that movie. It was a film we may have revisited a couple times after on VHS, but it was never an enjoyable experience — not like Dazed and Confused or Friday or Clerks, other films we consumed around that time ad nauseam. Beyond its surface-level voyeurism is pure real-life horror. Our own Jaws scaring us out of the water that summer. It’s probably not a film we’d ever want to watch again. It’s cringeworthy, especially after having all had kids of our own, and like so many older films, pretty damn problematic.

But who knows, it might’ve saved our lives.

Read more on Yahoo Entertainment: