“It was when we knew Roger Waters wasn’t going to be part of anything we did, but before he’d officially left. He had us trapped in limbo. I was putting my toe in the water”: David Gilmour’s solo career

In 2020 Prog writer Daryl Eastlea looked back over David Gilmour’s solo career beyond Pink Floyd, which amounted to just four albums to date, but also several production and countless session credits.

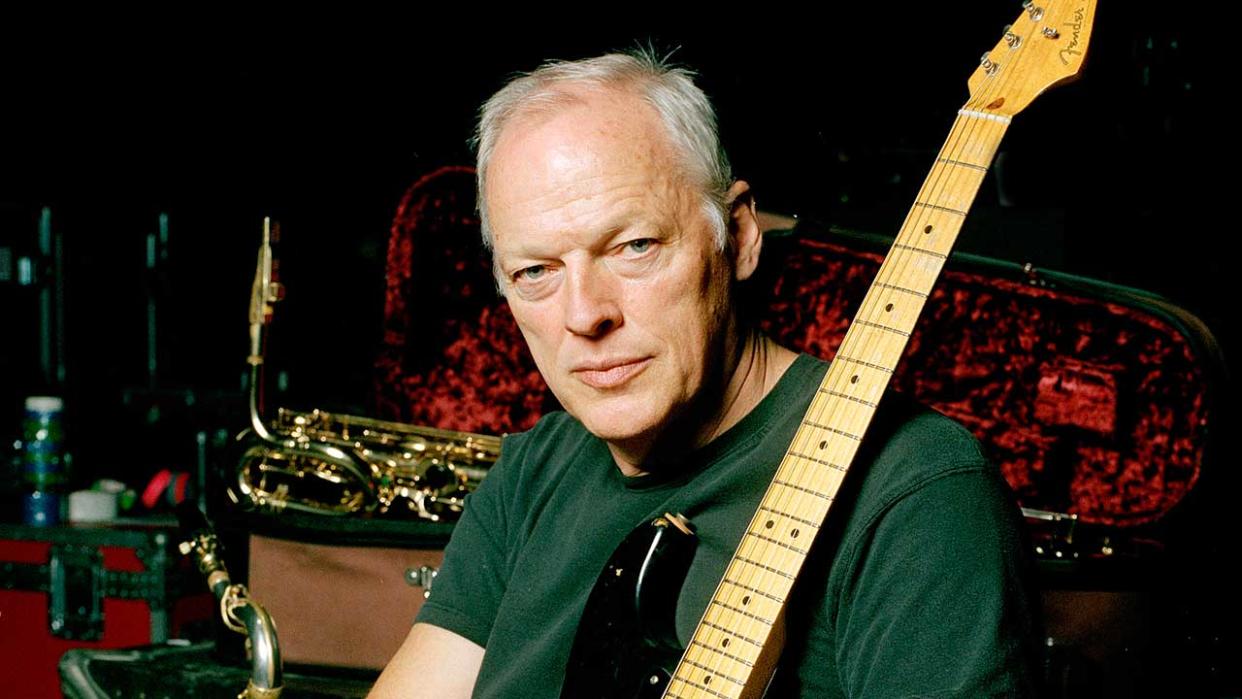

"For me it’s much less complicated to work alone,” David Gilmour said in 2006, with his characteristic understatement. Yet among those who would rate a David Gilmour album, few would even consider him – even after all these years – a solo artist.

Insteam most think of him, more now perhaps than anyone else, as the ongoing embodiment of Pink Floyd, the group he joined in late 1967 as a live replacement for Syd Barrett. Steady, strong-willed and undoubtedly his own person, Gilmour has stealthily sought to preserve the legacy of a group that – it could be argued – its other two leaders ( Barrett and Roger Waters) sought, if not to destroy, then certainly undermine.

Gilmour has never been especially prolific, or taken to the stage with the same gusto as Waters, whose stadium shows in the 21st century have continued where The Wall left off. Gilmour works under the radar as much as a multi-millionaire lead guitarist with one of the most successful bands of all time can. He has let his playing speak for itself – his impeccable taste and career choices have marked him out as someone who has hardly been forced to do things he would rather not – unlike the final years of Pink Floyd under Waters.

Unlike other bands of their day, Pink Floyd were pretty insular and there were few guest appearances from them on others’ records. They stopped being together round the clock after the success of The Dark Side Of The Moon, and Gilmour began to dabble with production, working closely with country rockers Unicorn.

He oversaw their second album, Blue Pine Trees in 1974 and went on to produce another album and a half for them; but the Ken Baker-led outfit never achieved the acclaim they deserved. Gilmour would be luckier with his next A&R spotting – he paid for three demos for the young Kate Bush. It was an association that lasts until this day; Gilmour was spotted at the final show of her Hammersmith residency in 2014.

Released in May 1978, Gilmour’s self-titled first solo album was a classic example of getting one’s head together in the country during time off from his parent group. While Waters was off building The Wall, Gilmour got together with his pre-Floyd Bullitt/Flowers bandmates bassist Rick Wills and drummer Willie Wilson.

Aside from Barrett’s albums (which, lest we forget, were produced by Gilmour) and Waters’ soundtrack to The Body with Ron Geesin, David Gilmour was the first ‘proper’ Pink Floyd solo album.

Recorded in the South of France, David Gilmour has lovely moments. Cry From The Street has echoes of Sheep; the Shadows’ guitar lines of Mihalis; the Roy Harper collaboration Short And Sweet (Gilmour would appear on his 1980 album The Unknown Soldier); Raise My Rent has fabulous guitar parts (and towards the end a figure that would be used directly in Another Brick In The Wall Part II).

It was clearly Gilmour’s Dark Side/Wish You Were Here vision of the Floyd rather than Waters’ Animals one. In some respects it feels like the follow-up to Obscured By Clouds. Charting inside the Top 30 on both sides of the Atlantic, it was “good, but without the emotional peaks of the Floyd at its best,” The Guardian opined. “This album blatantly demonstrates just how much of the notorious Floyd ‘sound’ comes directly from Gilmour,” said Sounds.

“The first one was a quick blast,” Gilmour told this writer in 2002. “It was all Rick and Willie encouraging me to get going. We congregated in the south of France, knocked out a few jams. It was really off the top of our heads, it was fun – comparatively, compared to Pink Floyd.”

For Gilmour, Pink Floyd was about to become considerably less fun. In fact, one of the moments of relief was Comfortably Numb, which grew from an outtake from Gilmour’s first album, not unlike the track So Far Away. The success and the antagonism between Pink Floyd during The Wall led Gilmour to be the only member of the group available to re-record Money for 1981’s A Collection Of Great Dance Songs when Capitol wouldn’t licence the original to Columbia in the States.

After his request for more time to complete songs for consideration on The Final Cut was turned down by Waters, Gilmour made his next album in 1983 in Paris and London. It was recorded, as Gilmour said, “at a time when we knew Roger wasn’t going to be part of anything we did, but before he’d officially left. He had us trapped in limbo. I was putting my toe in the water.”

Appearing in March ’84, About Face was co-produced by Bob Ezrin and its arrangements were by Michael Kamen. With the Kick Horns, Anne Dudley on synthesisers and at least two members of Paul Young’s The Royal Family, it is an archetypal mid-80s artefact. The album’s most successful track, You Know I’m Right, was a supposed barb at Waters.

“Roger addresses himself to whole problems in life and then tries to expand and broaden that and make a whole album fit around that sort of idea,” he told The Boston Globe in 1984. “He wants to explore that idea in very, very, very great depth from many angles, which I don’t have any disagreement with. But there are moments when I personally would not make some of the things quite so preachy and complaining.”

It’s not that Gilmour didn’t go in for some discussion of the hot ideas that were floating round – Cruise looked at the cruise missiles that were then stationed in Britain; Murder was a take on John Lennon’s assassination. Gilmour’s first solo tour followed, with a band including Mick Ralphs on guitar and Chris Slade on drums. The shows featured but three Floyd songs; a balance that would be redressed in future.

During this extended limbo period, Gilmour did various sessions: “I was bored and flattered to be asked,” he said. “Some of the things I don’t have a lot of affection for, and some I’ve never even heard. I can become a perfectionist when I'm with Pink Floyd, but going in, doing a guitar solo and then leaving is great.”

He produced the Dream Academy’s Life In A Northern Town, and his work can be heard on About Face collaborator Pete Townshend’s White City: A Novel album, Grace Jones’ Slave To The Rhythm and Bryan Ferry’s Boys And Girls. It was through this connection that Gilmour became the sole Pink Floyd representative at Live Aid, playing as a session man with Ferry’s band.

Suddenly, there was no need for more solo work – Roger Waters left Pink Floyd, declaring it over. “I was unencumbered and carried on doing Pink Floyd,” Gilmour recalled in 2002. “There didn’t seem to be any reason to do a solo project.”

He rebuilt Floyd and took it forward with two studio albums (A Momentary Lapse Of Reason in 1987 and The Division Bell in 1994) and two live albums (Delicate Sound Of Thunder in 1988 and Pulse in 1995). Roger Waters may have been winning an intellectual argument but Gilmour was campaigning hard for the heart and soul of the group.

After the last Floyd tour finished in October 1994, Gilmour retreated to a world of playing as a session man, most notably on Paul McCartney’s Run Devil Run album. Playing live at the Cavern with the Beatle in December 1999, Gilmour managed to persuade McCartney to sing I Saw Her Standing There, with Gilmour doing the John Lennon parts.

“I didn’t know what to do with leisure time, but now I’m quite good at it,” Gilmour told The Guardian in 1978. As the 21st century dawned, Gilmour had become very good at filling his time with his marriage to writer Polly Samson and his new young family. Intermittent Floyd business would always be in the background, like working collectively (remotely, of course) on projects such as 2001’s Echoes greatest hits package.

Gilmour made a rare solo appearance at Robert Wyatt’s Meltdown at London’s Royal Festival Hall in 2001, and, enjoying the experience, booked his own solo gigs at the same venue in 2002. It marked the rebirth of Gilmour as a solo artist.

The shows were a low-key celebration of his career, and included more Floyd songs than he had ever played live before on his own, with the ‘doctor’ part of Comfortably Numb being played by Bob Geldof and Robert Wyatt. It established a tradition of Gilmour working with a ‘guest doctor’ at a lot of his shows.

As the 00s progressed, Gilmour began work on a new album with his friend and collaborator Phil Manzanera. During recording, Gilmour received a call from Bob Geldof that was to pull off the unthinkable: a one-off Pink Floyd reunion. Few expected the group to play together for Live 8 in July 2005, and its memory grows ever more poignant – the image of Gilmour in full (un)comfortable strum beside the double-denimed Waters, marking the final time that all four Floyd members would be on stage, with mention and image of Syd Barrett on the screens, in the park where the group had played free concerts in the late 60s. Gilmour was later to dismiss the performance as “sleeping with your ex-wife.”

Released eight months after Live 8, On An Island – the album on which he’d been working – was remarkable. Secure in the knowledge that, if anything, his Floyd had triumphed in the bitter battle with Waters, he could make the album that he wanted, 22 years after About Face. On An Island was described by The Times as “a doddery old uncle to Floyd’s 1975 opus Wish You Were Here,” before continuing it was “a sort of sun-dappled Saga-rock in contentment is tempered by an attendant awareness of mortality.”

It was business as usual, and everything you would expect from a Floyd album. The instrumental Castellorizon that opened the album gave it an immediate familiarity – with Gilmour’s lonesome solo guitar riffing, emerging from banks of synths, before collapsing into the mellow title track, supported by Graham Nash and David Crosby on vocals. Take A Breath upped the tempo, but, generally speaking, it was an ultra-pleasant, mid-paced, well-written, beautifully produced work.

It was the tour that supported the album that found Gilmour able to stretch out and create an amazing combination of old and new. There was almost a tacit acceptance of what most of the audience wanted to hear, and Floyd warhorses were duly brought out of the stable, while – just like Floyd had done in the 70s – the new album, in this case, On An Island, was played in its entirety in the show’s first half.

Gilmour’s residency at the Royal Albert Hall was poignant. On May 29, 2006, David Bowie joined Gilmour on stage to sing Arnold Layne, Pink Floyd’s first single from 1967 (when Bowie was just beginning). He continued by playing the guest doctor on Comfortably Numb.

The Telegraph said: “A grey-suited David Bowie strolled on to supply a beautifully apt mockney… As the lights went mental, and Bowie and Gilmour duetted on Comfortably Numb, a patchy show miraculously pipped Pink Floyd for drama in the end.” It was to be Bowie’s final UK appearance.

Less than six weeks later, Barrett died, aged 60. Gilmour had been the keeper of the flame for years, ensuring Barrett’s material was not only played live by Pink Floyd or himself, but also placed on live releases.

It was with regret that he had not reached out: “I did know where he lived; I could have invited myself in for a cup of tea,” Gilmour said in 2007. “Syd and I were friends as teenagers and had a lot of memories that had nothing to do with Floyd. Some of that might have cheered him up.”

The tour was captured on the fine Live In Gdansk LP set, and the film of the Royal Albert Hall shows – Remember That Night – was released on DVD in September 2007. It was heralded with a screening and live extravaganza at the Odeon Leicester Square.

As well as the film, Gilmour took to the stage to play Castellorizon, and then, later, played a loose 10-minute jam with Rick Wright, Guy Pratt, Jon Carin, Phil Manzanera, Dick Parry and Steve Di Stanislao. It was to be Wright’s final ever live performance; Gilmour’s keyboard foil was to die in September 2008.

In summer 2010, Gilmour asked Waters to help him to raise money for the Palestinian children’s charity Hoping Foundation. In July, in Oxfordshire, the duo appeared together to play four songs with a band that included stalwarts Guy Pratt and Waters’ son Harry.

Together they sang, with a ladling of irony, To Know Him Is To Love Him and then Wish You Were Here, Comfortably Numb and Another Brick in the Wall (Part II). The quid pro quo was simple – as a thanks to Waters, Gilmour would play his most famous solo on Comfortably Numb at one of Roger Waters’ solo The Wall shows at London’s O2 Arena the following May. On May 12, Gilmour kept his promise and later that same night Nick Mason joined them for show closer Outside The Wall, and the surviving Pink Floyd were united once again.

Although the constant question of a permanent reunion is forever there, Gilmour was unequivocal to Rolling Stone in 2014: “I was in my 30s when Roger left the group. I’m 68 now. It’s over half a lifetime away. We really don’t have that much in common any more.”

In October 2010, Gilmour collaborated with The Orb, and released Metallic Spheres. A most pleasant surprise, it located Gilmour at the edge of space rock again, with his aching solos over Alex Paterson and Youth’s soundscapes. The Metallic side had some of Gilmour’s best playing of recent years; removed from expectations, he delivered something sweet indeed.

If Live 8 had been the full stop to Pink Floyd’s sentence, The Endless River – compiled initially from jams and outtakes around The Division Bell, which arrived in November 2014, was the perfect postscript and dedicated to Rick Wright, whose playing throughout was superb. Again, it was Gilmour’s vision of Pink Floyd, compiled leisurely by trusted lieutenants.

It was time for Gilmour to pick up his solo career; his fourth solo album, Rattle That Lock, was released in September 2015. It was loosely based on the contrasting thoughts and feelings people have in the course of a single day: a beautifully mellow rumination on life, love and ageing.

The John Milton-inspired title track, built around the French railway company SNCF’s call sign, bounced more than Gilmour’s work had in years. Among the album’s highlights were A Boat Lies Waiting, an emotional tribute to Wright, with simple, fluid grand piano played by Roger Eno.

As expected, the tour to support Rattle That Lock was stunning, taking in the UK, North and South America, and two visits to Europe. For the final shows Gilmour was rejuvenated by a personnel change (with only Guy Pratt remaining from the previous outfit).

The band played live in the Pompeii amphitheatre where Floyd had filmed in 1971. The film released of the concert was spectacular: Stage lights swell and subside in accordance with the music, and all the players look to be having a wonderful time, especially on One Of These Days, the only song to appear in this and Floyd’s original film.

One of the reasons Gilmour may not be viewed as a solo artist is his lack of releases. In fact, in the past two decades, Gilmour has become known for his philanthropy through the DG Foundation as much as his output. His increased share in sales Pink Floyd experienced after Live 8 was donated to causes close to Gilmour, as were the proceeds of his London townhouse, which he sold for £3.6 million in 2002, going to Crisis.

“You can’t live seriously in more than one house. Everything else is just a holiday home,” he said at the time. With his latest act of altruism, the thought of Gilmour being parted from his famous guitars may be just too much for some fans to bear, suggesting that it is really all over. You never quite know what David Gilmour will do next. One thing is for sure: it will hardly be in haste.