"I know me and I know my playing... and then there's Rain": The story of The Beatles' greatest b-side

Day Tripper, I Feel Fine, Revolution, Lady Madonna, Hey Jude, We Can Work It Out, She Loves You, I Want To Hold Your Hand, Don't Let Me Down… just some of The Beatles' classics that never made a studio album.

That's how good Paul, John, George and Ringo were in their seven years, seven months and 24 days together as a band. But there's a true Beatles b-side that fascinates even more than those songs, and it found them and their studio geniuses at the point of accelerated evolution.

“This is a song I wrote about people who are always moaning about the weather all the time,” John Lennon once said of the Revolver-era Rain. The word 'I' there suggesting the Lennon / McCartney credit the song carries needn't apply.

This is in contrast to Lennon's memory of the genesis of Rain's A-side, Paperback Writer's. "I think I might have helped with some of the lyrics," he told Hit Parader Magazine in 1972. "Yes, I did. But it was mainly Paul's tune." But he clearly saw Rain as his song. Indeed, in the same interview, it was one of a number of Beatles songs he listed as being written by himself.

Paul McCartney remembered things differently. Though noting Lennon was the more dominant contributor to the song, he said it was still a "70-30" authorship and seemed to play the idea of his late bandmate as its instigator down. “I don’t think he brought the original idea, just when we sat down to write, he kicked it off,” McCartney claimed to Barry Miles in his 1997 biography of the Beatle, Many Years From Now.

“Songs have traditionally treated rain as a bad thing and what we got on to was that it’s no bad thing," he said of its inspiration. "There’s no greater feeling than the rain dripping down your back.”

Authorship aside, McCartney and Lennon's reading of Rain's songs's lyrical meaning seems to be quite literal, but on the sonic side, it was clear Lennon may have wanted to go much further on Rain than what the band ended up releasing.

“It was the first time I discovered [backward music],” he told Rolling Stone in a 1968 interview. “On the end of Rain you hear me singing it backwards. We’d done the main thing at EMI and the habit was then to take the songs home and see what you thought a little extra gimmick or what the guitar piece would be.

I staggered up to me tape recorder and I put it on, but it came out backwards

“So I got home about five in the morning, stoned out of me head," Lennon remembered after recording the main session in the studio. "I staggered up to me tape recorder and I put it on, but it came out backwards, and I was in a trance in the earphones, what is it — what is it?” he said.

Lennon was hooked on what he heard. “It’s too much, you know, and I really wanted the whole song backwards almost, and that was it,” he admitted. “So we tagged [the backwards part] on the end. I just happened to have the tape the wrong way round, it just came out backwards, it just blew me mind.”

This small outro seemed revolutionary for a pop song in 1966 – coming just over two months before the release of Tomorrow Never Knows on revolver. But despite Lennon's belief that it was "the first backwards tape on any record anywhere", it wasn't. Backmasking – purposefully recording a vocal line backwards onto tape – dates back to the 1959 song Car Trouble by US vocal group Eligibles adding some comedy lines from an imagined girlfriend's angry father. But the Beatles' first use of it brought it into a sharp mainstream focus that was a far cry from the novelty, though trailblazing context of the Eligibles.

Revolver closer Tomorrow Never Knows is the most famous use of a backwards guitar solo (played by George Harrison) and probably came first as far as a studio recording is concerned (recording on it began about a week before Rain and Paperback Writer). Lennon's happy accident with Rain came in the same month of April 1966. But there's much more to this song to define it as not just historically important, but progressive is terms of musicianship and sound.

This extends to the other Beatles and the unofficial members outside of the Fab Four. Producer George Martin and the experimental spirit of engineer Geoff Emerick's moves towards changing the role of a recording studio from simply capturing performance to playing an instrument-like role in musical creation were coming to fruition.

My favorite piece of me is what I did on Rain

It was Emerick – then just 20 years old and newly made engineer for the Revolver sessions on the recommendation of George Martin – who decided to amplify the dynamics of Ringo Starr's intricate fills on the song against the recording conventions of EMI at the time. The results delighted the drummer, but it's hard to deny he drew something extra from himself with his performance.

"My favorite piece of me is what I did on Rain," Starr reflected in 1984. "I think I just played amazing. I was into the snare and hi-hat. I think it was the first time I used the trick of starting a break by hitting the hi-hat first instead of going directly to a drum off the hi-hat.

"I think it's the best out of all the records I've ever made. Rain' blows me away. It's out in left field. I know me and I know my playing... and then there's Rain."

The song, the sound, the feel – Rain sounds like British indie rock decades ahead of its realisation. No wonder it inspired Liam Gallagher & Co's pre-Oasis moniker before brother Noel changed their fortunes with Live Forever. Emerick's influence on the sound of Rain went even further than Ringo.

Rain also had an unusual sonic texture, deep and murky

"Rain also had an unusual sonic texture, deep and murky," recalled the late engineer in the Howard Massey co-written 2006 book Here, There And Everywhere: My Life Recording The Music Of The Beatles. "This was accomplished by having the band play the backing track at a really fast tempo while I recorded them on a sped-up tape machine. When we slowed the tape back down to normal speed, the music played back at the desired tempo, but with a radically different tonal quality."

The Beatles' studio team had already discovered the value of this in the Tomorrow Never Knows sessions, but the practical reality of what was needed to achieve it is striking. The band played the original speed in the key of A (or not quite as I'll explain later), and when slowed it was in the key of G. Take a listen to the instrumental recording of Rain above to hear just how fast that original backing track speed was too.

The performances beyond Starr's also play crucial parts in this crafted psychedelic three-minute wonder. The bassline is surely one of McCartney's greatest in a notable period for his low-end prowess. A sibling of Revolver's Taxman, his verse parts don't repeat as his inventive melodic lines flow through the changes of what is mostly just two chords (G major and Csus2). McCartney's groove has a suitably watery quality in the song.

McCartney's bass was arguably more prominent on Rain and Paperback Writer than on any previous Beatles recording. He was bolstered by the sustain of his ’64 Rickenbacker 4001S – a move from the Hofner influenced by the more powerful low-end mix he was hearing in Motown soul from the US of the time. But the guitars are less simple to credit for sure.

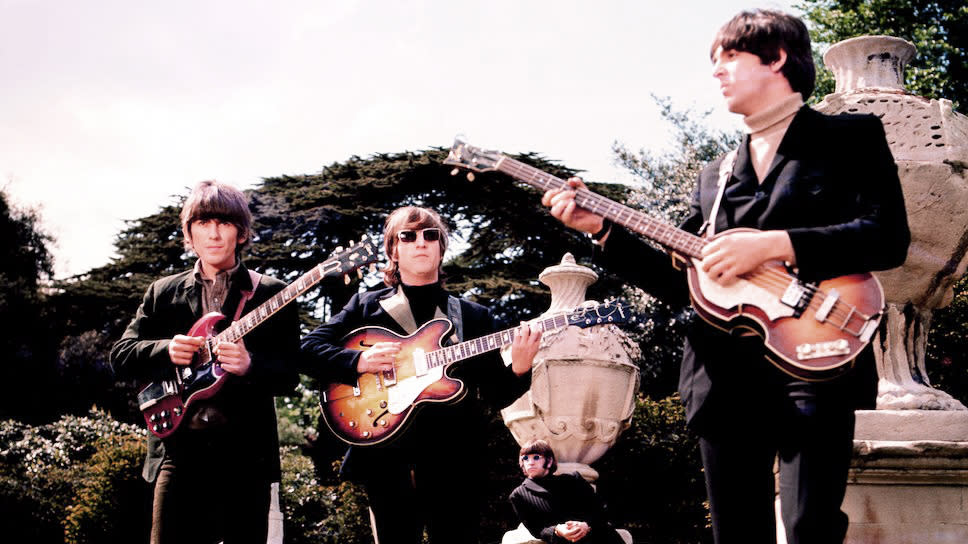

Rain was tracked during the two sessions on Thursday 14 April 1966 – recorded the day after the majority of Paperback Writer was laid down. Work on the track, including overdubs and mixing was completed on 16 April with the song released with Paperback Writer on 30 May. We know from Andy Babiuk's superb Beatles Gear book that for the A-side session Lennon was photographed in the studio with a newly acquired orange Gretsch 6120 around that time - that was reportedly never seen again afterwards.

It's tempting to attribute the droning quality of Harrison's arpeggiated chords to that of the Indian classical music Harrison had discovered during the filming of Help in 1965. This had resulted in the use of a sitar on Rubber Soul's Norwegian Wood later in the same year. The tape manipulation certainly aided to the ethereal quality of Rain's guitar, and the electronically double-tracked vocal sounds pioneered by Abbey Road engineer Ken Townsend played their part too.

The guitars were originally tuned above concert A in reality before the recording was slowed down – somewhere around A#

The band recorded five rhythm takes for the song in Abbey Road's EMI Studio 3 with the fifth decided as the keeper. Lennon also sang vocal harmonies with himself on the chorus. But hearing the original speed version of Rain still reveals an atonal quality to the guitar that feels slightly sitar-like to my ears. And it's due to the tuning. As Mike Pachelli reveals in his insightful lesson above, the guitars were originally tuned above concert A in reality before the recording was slowed down – somewhere around A#.

It's never been confirmed for certain what guitars were used on Rain. There are a three in contention; an Epiphone Casino, Lennon's new Gretsch or George's mainstay 1964 Gibson SG standard he's seen with for one of the song's multiple promotional videos.

Yes, videos in the plural – seven in total for between Rain and Paperback Writer. The former's three videos were not just unusual for a Beatles b-side, but arrived at a time when the precedent of any promotional video for a song didn't exist. The idea came about for a very specific reason.

It was great, because really we conned the Sullivan show into promoting our new single by sending in the film clip

"The idea was that we’d use them in America as well as the UK," Harrison explained in the Beatles' Anthology book. The guitarist had been keen for the band to focus on studio work over promotional live performances and the concept of a video suited these ends. "Because we thought, ‘We can’t go everywhere. We’re stopping touring and we’ll send these films out to promote the record.’ It was too much trouble to go and fight our way through all the screaming hordes of people to mime the latest single on Ready Steady Go! Also, in America, they never saw the footage anyway.

"Once we actually went on an Ed Sullivan show with just a clip," Harrison added. "I think Ed Sullivan came on and said, ‘The Beatles were here, as you know, and they were wonderful boys, but they can’t be here now so they’ve sent us this clip.’ It was great, because really we conned the Sullivan show into promoting our new single by sending in the film clip. These days obviously everybody does that – it’s part of the promotion for a single – so I suppose in a way we invented MTV.

Add that one to the list of Beatles innovations too then.