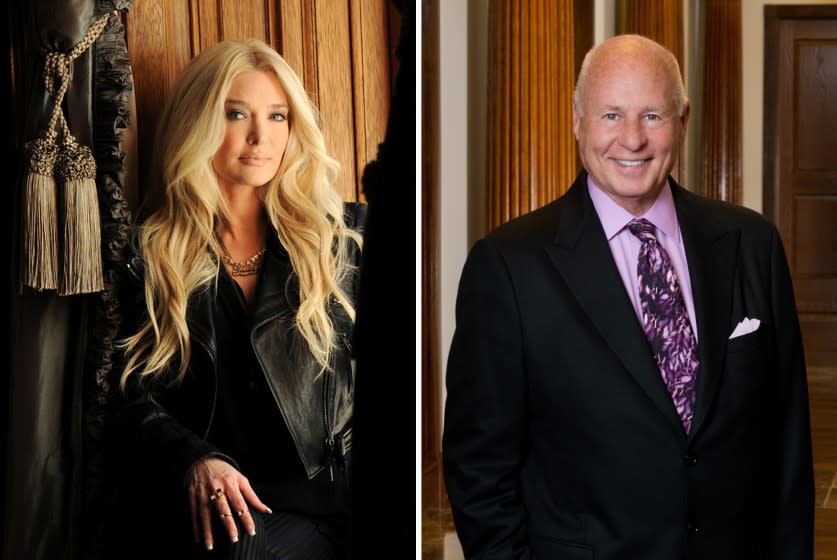

The legal titan and the 'Real Housewife': The rise and fall of Tom Girardi and Erika Jayne

From his Wilshire Boulevard office, Tom Girardi has dominated consumer law in California and beyond for decades, wresting billions of dollars from drug companies, carmakers and polluters on behalf of the injured and cheated, most famously in the case that inspired “Erin Brockovich.”

His cut of those legal victories, up to 40%, brought him spectacular wealth. With his third wife, a pop singer known as Erika Jayne, he appears on “Real Housewives of Beverly Hills,” flaunting the couple’s historic Pasadena estate and lifestyle: private planes, jewelry, exotic cars, couture-filled closets and vacations in Aspen and Mykonos.

The millions Girardi poured into Democratic political campaigns made him a confidant of generations of power brokers, including Gov. Gavin Newsom, who last year gave the attorney an official role in filling coveted state judgeships.

But now, in the twilight of his career, the 81-year-old is facing the collapse of everything he holds dear — his venerable law firm, marriage and reputation as a champion for the downtrodden.

He stands accused of stealing millions of dollars from vulnerable clients, including Indonesian children orphaned by a plane crash and a burn victim in the Pacific Gas & Electric pipeline explosion. His creditors have demanded payment in court, among them high-interest lenders, fellow lawyers, a security company that once guarded his Pasadena mansion, and his first wife. Nearly all the attorneys who worked at his firm, Girardi Keese, have left, including his own son-in-law, and last month Jayne petitioned for divorce.

Word of his downfall circulated through law firms and judges’ chambers in stunned whispers for months before bursting into public this week when a federal judge froze Girardi’s assets and called his mishandling of the Indonesian children's money “unconscionable.”

“At one point, I had about 80 million or 50 million in cash. That’s all gone,” Girardi acknowledged in testimony this fall about another client’s funds. “I don’t have any money.”

It was an extraordinary admission from a titan of American law who strode the courthouse halls with an aura of invincibility and whose name had become synonymous with massive windfalls.

Where all the money went remains a topic of intense speculation, and neither Jayne nor Girardi's representatives responded to requests for comment. Some creditors have pointed to his much younger wife. Girardi has underwritten Jayne’s attempts at fame as a recording artist with songs titled “PAINKILLR” and “XXpen$ive” and as a reality TV figure who boasts of dropping $40,000 a month on clothes, hair and makeup.

In court filings last year, a company that loaned money to Girardi Keese for business expenses suggested Girardi improperly funneled more than $20 million to Jayne’s entertainment company.

He has bristled at allegations that he diverted firm assets for lavish living, but his lawyers admitted in court this week that he has been unable to tell them what happened to the money.

Warning signs beyond the 'Real Housewives' glitz

Hints of serious financial troubles at Girardi’s law firm surfaced around 2015. At the time, he and his wife were becoming household names, thanks to producers who cast them in the Beverly Hills edition of Bravo’s “Real Housewives,” on which she appears as Erika Girardi.

Girardi was then in his mid-70s but expressed no interest in retirement. His high energy and obsession with the law were part of his persona on the show, and he publicly admitted having few hobbies and no succession plan at the firm he co-founded five decades previously.

“I’m finally getting good at this,” he joked to one reporter.

A lawyer since 1965, Girardi had won a name for himself in medical malpractice, securing what he touted as the first verdict in California in excess of $1 million. He’d gone on to conquer the nascent field of toxic torts. One of those environmental pollution suits, brought on behalf of residents of the Mojave Desert town of Hinkley, resulted in a $333-million settlement with PG&E that supercharged his career.

It was due less to the allegations — that tainted drinking water had caused cancer and other ailments — than to the 2000 movie it begat. Julia Roberts portrayed the titular paralegal Brockovich as a scrappy heroine whose short skirts and persistence made environmental litigation easy to absorb and improbably sexy.

The film reduced Girardi to a composite figure, but he, and later his wife, used it as a calling card announcing his importance.

“All of a sudden, I was part of a very public win that a lot of people understood,” Girardi recalled this year in an interview with a professional association honoring him. “The case did me an awful lot of good, to put me into a category that, ‘Hey, you know this guy can handle these big cases.’”

Victims sought out Girardi Keese. Other lawyers referred cases to him, believing in his ability to take on deep-pocketed corporations.

The problems that emerged around 2015 stemmed from one of those David-versus-Goliath cases: A $17-million settlement for 138 senior-citizen women who claimed they developed cancer after taking hormone replacement therapy.

The payout the women received from Girardi’s firm did not match the sum they anticipated. They requested an accounting.

The firm refused, and in 2014, about two dozen women filed suit against Girardi and the firm. Girardi’s lawyers insisted he had done nothing wrong, but they kept ignoring requests for bank records, emails and other documents despite orders from a federal magistrate, court records show.

The women became increasingly frustrated. Their lawyers alleged in filings that the firm had misappropriated more than $10 million and suggested the held-back documents “would reveal the fraudulent and criminal nature of their wrongdoing.”

As the case moved toward trial, Girardi borrowed $12 million at a high interest rate from a Northern California company that specialized in funding law firms, and an additional $5 million from a similar lender in Arizona, according to timelines they later detailed in court papers. Within months, he reached a settlement with the cancer survivors.

It was not the last time Girardi would have to borrow.

Those watching on Bravo were none the wiser. In their first episode, Girardi and Jayne gave viewers a tour of their gardens, designed by the Olmsted brothers, who planned Central Park. Jayne explained how she balanced being a Pasadena socialite with a secret life as a risqué performer of dance hits.

“If I don’t honor my inner bad girl,” she told the audience, “I’m not going to be happy.”

A chance meeting at Chasen's, and a new life

Girardi met Jayne in the late 1990s at Chasen’s, the famed Beverly Hills haunt where he was a co-owner and she waited tables in the bar. Jayne, then known as Erika Chahoy, was a striking, blond 28-year-old with a young son and dreams of stardom. Girardi was 60.

“He’s well read and educated. That kind of stuff is a powerful aphrodisiac,” Erika wrote in her 2018 memoir “Pretty Mess.” “When someone is positive, successful, loving, inspirational — I got to tell you right now … That is more enticing to me than six-pack abs and a chiseled jawline.”

She soon moved into what Girardi has described as a five-acre compound overlooking the Rose Bowl and quit Chasen’s. On her last day, she tossed her work uniform — a clingy, velvet emerald green dress and black heels — in the bar trash can.

“Closing the lid, I walked out of that restaurant and into a whole new life,” she wrote.

The couple married in the clubhouse of the Los Angeles Country Club in 2000. Girardi asked a judge he knew to officiate at the end of a round of golf. The wedding was so spontaneous that the groom enlisted an attorney in the bar as a witness. Although Girardi was in the midst of an acrimonious dispute over dividing assets with his second wife, he opted not to sign a prenuptial agreement.

Taking risks was part of Girardi’s nature — and his business. His firm’s bedrock was contingency cases. In those, clients do not put up a cent. Their lawyers front the costs of investigating the claim and putting on a trial. If they win, they collect their costs and 25% to 40% of the award. If they lose, they get nothing.

“I think the whole world should be on a contingency basis,” Girardi said to a reporter in 1996. “If you don’t cure the problem, you shouldn’t be paid.”

For a long time, it seemed to work well; Girardi racked up scores of verdicts over $1 million.

The cases brought so much business that Girardi expanded the firm into an adjacent building on Wilshire Boulevard. By 2001, his monthly income was nearly $263,000, according to a divorce filing. Unlike firms where lawyers can work their way up to equity partnerships, Girardi retained 100% of the corporation.

“It was clear to everyone that it was his firm and only his firm,” said Graham LippSmith, who worked at Girardi Keese for 13 years and left in 2015.

Still, jobs there were much sought after by law school graduates. There were material perks for his lawyers — Girardi paid for luxury cars and brought in a tailor to make them custom suits and shirts, according to people familiar with the firm. Girardi Keese had a box at Staples Center, and attorneys had an ample budget for wining and dining potential clients and co-counsel.

Working for Girardi meant being in the orbit of the powerful and well connected. He counted among his friends the late Johnnie Cochran, at one point floating the L.A. legal legend $650,000, divorce records indicate. He belonged to country clubs across L.A. and was a regular at Morton’s, Pacific Dining Car and Madeo.

Judges, lawyers and civic leaders rubbed elbows at Girardi’s holiday and Super Bowl soirees. At those parties and legal conferences, he spared no expense for performances by Jay Leno, Burt Bacharach, LeAnn Rimes and Penn & Teller.

He could get former Gov. Jerry Brown on the phone with ease, associates said. Former Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid got him appointed to a Library of Congress board.

A Times analysis identified at least $7.5 million in political contributions from Girardi, his relatives and employees to candidates and political committees, from city council races to presidential campaigns. Jayne alone made more than $1.3 million in political contributions during their marriage, records show.

Most of the contributions went to Democrats, including Joe Biden, who turned to Girardi and Jayne when he came to L.A. to raise money. The pair hosted the president-elect for an event last year at the Jonathan Club, a private downtown social club.

Newsom named Girardi last year to a panel that evaluates potential judges in L.A. County. While lieutenant governor, Newsom told the executive producer of the “Real Housewives” franchise, Andy Cohen, that Jayne’s husband was “extraordinarily generous” to his campaigns.

“So she is my favorite ‘Real Housewife,’” he said with a smile.

A rocky music career, then fame on 'Real Housewives'

The Italian American Lawyers Assn.'s annual “Supreme Court Night” was normally a tasteful affair, with attorneys and judges gathering in a Biltmore Hotel ballroom for an orchestra performance and remarks by California’s justices.

Then there was 2011. Girardi, the association president that year, announced a special treat for the audience: A screening of his wife’s latest music video. For the next four and a half minutes, the justices watched with the rest of the crowd as a scantily clad Jayne gyrated on screen.

The Metropolitan News-Enterprise, L.A.’s century-old legal newspaper, termed the event “a fiasco.”

“Set at a smoke-filled party, the video, if I’m correctly advised, includes a woman partyer pouring liquor on a man’s bare chest and lapping it up,” wrote newspaper editor Roger Grace. Judges were “absolutely beside themselves,” Grace recalled in a recent interview.

The video was part of Jayne’s midlife attempt at a recording career. A decade into her marriage, she had grown bored with being the wife of an extremely wealthy lawyer.

“There was nothing more I could buy,” she wrote in her memoir. She feared being “relegated to a life of shopping, sitting on a few charity boards of no consequence, and standing silently by my husband’s side full of unrealized potential.”

She decided to launch herself into the music industry as a bawdy dance diva and presented Girardi with a spreadsheet of her desired production budget. “He was a billion percent supportive,” she wrote in the memoir.

His deep pockets made for advantages few rookies could imagine: Michael Jackson’s choreographer; a songwriter who had worked with Madonna, Stevie Nicks and Britney Spears; and a costume designer for Lady Gaga and RuPaul.

In the years that followed, she found some success. She has had nine hits on Billboard’s dance charts, toured in Asia and developed a cult following in the LGBTQ community. Girardi was often on hand for shows, she wrote, sometimes even picking up checks from club managers.

Some of her husband’s lawyer and judge friends rolled their eyes.

“Boy, they hated my a—,” she would later tell “Real Housewives” viewers. If it bothered Girardi, he did not let it show.

By 2015, she was preparing to close down her costly music ventures. As she recalled in her memoir, “The return on investment wasn’t really making sense anymore.”

But before she could announce her retirement, she was cast on “Housewives.” Her TV persona was built on the tension between her marriage to a much older, famous attorney and her dance hall image as an oversexed, cash-obsessed pinup. She threw herself back into music, launching and pushing out videos, including one in which she sang, “It’s expensive to be me” while writhing on a bed covered with money.

"I like the fact that it is named ‘XXpen$ive,’” her husband said on “Housewives” of the single. “It kinda suits you.”

Troubles at the law firm

While Jayne and her castmates frolicked in Italy and the Bahamas, Girardi was working quietly to keep his law firm afloat.

Although few at Girardi Keese or the larger legal community knew it, he went back to high-interest lenders again and again for help. He was so secretive that the companies giving money did not know there were other lenders holding the same collateral, according to a lawsuit filed by one lender and a sworn declaration by another company.

The collateral Girardi put up for the loans was the anticipated fees of a number of large contingency lawsuits, court records show. At various points, these included the litigation over the Porter Ranch gas leak and cases against the National Football League, Shell Oil Co., the maker of the diabetes drug Avandia, and others. The loans were made at rates of up to 20%, with even higher interest for missed payments.

He presented himself to them as a safe bet. He tallied his net worth in an affidavit two years ago at $264 million, including ownership interest in two planes; $9 million in jewelry “at cost;” $3 million in antiques, art and furniture; and his Pasadena estate, which he valued at $15.5 million.

“Conservatively, our fees for 2016 will be in excess of $110,000,000,” he wrote in an affidavit submitted that year to the chief executive of a company named American Law Firm Funding. He noted additional assets — a Temecula real estate investment and shares of a Nevada casino operator — and then mentioned his wife’s career. “I believe that the Erika Jayne record sales and performances will be worth a large sum of money, but I believe it’s a little too speculative to make it [a] substantial factor.”

Her star did seem to be on the rise. She competed on “Dancing With the Stars.” Her breezy, ghost-written autobiography made a brief appearance on the New York Times’ bestseller list. She deejayed at a Coachella event, and in a marker of mainstream fame, appeared on "The View," where guest host Alyssa Milano quizzed her on life with the “inspiring” lawyer from “Erin Brockovich.”

"I’m glad you said that,” Jayne replied in the 2018 broadcast. “Cause that's a lot of the reason that I had the courage to go be Erika Jayne was because of my husband.”

Meanwhile, Girardi’s creditors were growing concerned. The lenders expected that once Girardi settled major cases for millions, they would get their money. But Girardi Keese wasn’t paying its debts.

Law Finance Group, a Northern California lender, had access to some of the firm’s records and didn’t like what it was seeing. Company officials noticed, as its chief executive would later write in a sworn affidavit, that “very substantial sums, denominated as ‘loans’” were going from firm accounts to EJ Global LLC, the company set up for Jayne's performing career. The amount transferred topped $20 million, according to the affidavit.

“It became frustrating and impossible to get the money,” the CEO, Alan Zimmerman, recalled in an interview.

After nine months of demanding repayment, LFG filed suit in 2019, alleging that money loaned to the firm had been spent partly on “Mr. Girardi's lavish lifestyle.”

Girardi was enraged.

“Your claim that I used one penny of the funds for my ‘lifestyle’ is total fraud,” he steamed in a letter to LFG’s lawyers. “Four judges called me after they saw the lying materials. ... Every one of them stated [the opposing lawyers] better not come in his courtroom.”

Girardi managed to settle with the lender, but other creditors were already lining up at L.A. County Superior Court.

A company that provided back-office services for class-action suits demanded $7.5 million, an expert witness wanted $40,000 in fees, the security company that provided an armed guard at the Pasadena estate said it was owed $53,000, and a Long Beach lawyer who had referred cases to Girardi sued for nearly $4 million, according to lawsuits each filed.

Girardi’s first wife, with whom he split in 1983, revived a case that had sat dormant for decades to complain that her $10,000-a-month alimony payments had stopped abruptly, court records show.

In the swirl of creditors, one young man stood out. Joseph Ruigomez suffered burns over 50% of his body during the 2010 PG&E pipeline explosion in San Bruno, when he was 19. Girardi's firm had negotiated a substantial confidential settlement. But in the years that followed, his family concluded that the lawyer had misappropriated millions of dollars of their money.

Stealing client money is a very serious allegation for attorneys. Lawyers can be disbarred and even charged criminally for such conduct. In January, Girardi signed an agreement to pay the Ruigomez family $12 million. But after paying $1 million, he stopped.

The family had had enough. Their lawyers hauled Girardi into court and made it clear they would go to great lengths to get the money. They informed state and local governments that they had a claim on Girardi's assets and put a lien on a $23-million settlement he had won for a double-amputee injured in a car accident. They served legal papers on the Girardi Keese accountant; Girardi’s personal travel agent; Jayne; his son-in-law; and even the membership director at the Jonathan Club, where, they noted, initiation fees ran $45,000.

Prepare to testify under oath about the state of Tom Girardi’s finances, the legal notices announced.

In the Wilshire Boulevard offices, people who had worked with Girardi for decades were becoming nervous, according to individuals familiar with the situation. He had complete control over the finances and was secretive about them. Where had all the money gone, they asked each other.

Lawyers started leaving. In June, David Lira, Girardi’s son-in-law, resigned on a Saturday. The firm that once had 30 lawyers was soon down to single digits.

The situation only worsened for those who remained. A Chicago firm that had helped represent four Indonesian families with loved ones killed in a 2018 plane crash kept calling about missing settlement money. Boeing had already transferred about $2 million for each plaintiff, so why hadn’t the families received all their money, the Chicago lawyers asked.

When they finally reached Girardi in July, he offered an “extremely convoluted and meandering” explanation of what happened to the funds, according to a lawsuit the attorneys later filed. Another firm lawyer, Keith Griffin, later told them half of the money had been paid and more was on its way, even claiming to have seen the wire transfer confirmation, according to court filings. But the funds apparently never arrived and Griffin later admitted that “Girardi hadn’t actually paid the clients [and] that he was skeptical that Girardi ... had the financial means to” do so.

Griffin did not return messages seeking comment. He quit the firm this month and told a federal judge this week that he was merely a firm employee, and that Girardi had sole control of the Indonesian clients' money.

'I would like the record to reflect there is silence'

In late September, Joseph Ruigomez’s attorneys finally had a chance to confront Girardi about his assets in a proceeding known as a judgment debtor exam. Testifying on a videoconference call because of the pandemic, the attorney seemed for the first time resigned about his financial situation. He said his stock portfolio of about $50 million was “all gone” and he had “maybe a couple thousand” dollars in a personal bank account, according to excerpts of a transcript filed in court.

Asked about his income, he said, “I haven’t taken a penny in salary out of the firm for more than two years.”

On the date set for Jayne’s testimony, she was out of town and it was rescheduled for January. She filed for divorce on election day, citing irreconcilable differences and indicating she planned to seek spousal support from Girardi.

He continued putting on a confident face to people demanding money. Girardi touted his firm’s representation of more than 8,000 plaintiffs in litigation against Southern California Gas Co. over the massive Porter Ranch gas leak, telling a creditor in a letter this summer, “I believe a very conservative estimate as to the settlement for our clients would be in the $900 million area.”

He left voicemails last month promising to make things right with the Indonesian clients.

“We screwed up here a little bit,” Girardi acknowledged in a call to one of the Chicago lawyers, adding, “I’m so sorry, this never happened before. Anyway, everything will be smoothed over on Thursday.”

It was not. This week, a federal judge in Illinois overseeing the Indonesian case ordered Girardi to appear before him to explain what happened to the $2 million due the victims’ families. One of the attorneys representing the crash victims, Jay Edelson, said in court that for at least the last decade, Girardi had been running his firm like “a Ponzi scheme.”

“What they do is when money comes in, they use that to pay previous creditors and previous clients, and then they wait till more money comes in,” Edelson said. “I guess everything just caught up with them.”

U.S. District Judge Thomas M. Durkin asked Girardi, “Why wouldn’t everything be paid to the plaintiffs upon receipt of the money?”

Neither Girardi nor two criminal defense attorneys he had recently hired responded.

“I would like the record to reflect there is silence,” the judge said.

Girardi’s legal team said their client had been unable to help them understand what became of the money. One lawyer said in court that Girardi “has had issues of his mental competence” and another asked the judge to order a “mental health exam.”

The judge referred Girardi to the U.S. attorney’s office for criminal investigation. He also froze Girardi's personal assets and those of Girardi Keese, a step that appeared to have come too late. As one lawyer told the judge, the firm’s operating account contained just $15,000.

Hours later, Jayne posted a picture in silver stilettos, elbow-length mesh gloves and lilac lingerie.

She captioned the image, “Put me on your wish list.”

Times staff writer Melanie Mason and staff librarian Scott Wilson contributed to this report.

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.