Leon Russell — a songwriter's songwriter, a musician's musician — is finally getting his due

Anyone tracing a path through the history of American soul music could do worse than to catalog the many, many renditions of Leon Russell’s “A Song for You.”

Start with Russell’s tender yet stately original, which opened his debut solo album in 1970 after the years he spent haunting Los Angeles recording studios — that’s him playing piano on the Ronettes’ “Be My Baby” and the Byrds’ “Mr. Tambourine Man” and the Beach Boys’ “California Girls” — as a member of the storied Wrecking Crew of first-call session musicians. Then move through Donny Hathaway’s virtuosic R&B aria, Willie Nelson’s cosmic-cowpoke ballad and Aretha Franklin’s queenly slow jam on your way to the pleading testimonial with which Ray Charles won a Grammy Award in 1994; skip ahead to hear later interpretations by Herbie Hancock and Christina Aguilera, Whitney Houston and — why not? — the pairing of rappers Bizzy Bone and DMX.

The latest to take up “A Song for You,” which salutes a partner for teaching the narrator “precious secrets of a true love withholding nothing,” is Monica Martin, who performs it on a new tribute album called “A Song for Leon” that also features Margo Price, the Pixies, Orville Peck, Bootsy Collins and Nathaniel Rateliff & the Night Sweats, among others. An L.A.-based singer and songwriter known for her collaborations with Marcus Mumford and James Blake, Martin does “A Song for You” as a hymn, more or less, with churchy organ rippling beneath her airy vocals.

“It’s such an unusual piece of music in that it’s very free-form but it still cradles you,” Martin says. “And some of the lyrics! ‘I love you in a place where there’s no space and time,’” she says, quoting one of Russell’s signature lines. “You don’t have to engage with the woo-woo nature of that, but it so captures that feeling where it’s like you’ve loved someone for multiple lifetimes, you know?

“It just makes you want to know more about what was going on in this man’s head when he wrote it.”

That’s the idea behind the 10-track “A Song for Leon,” due Sept. 8 from Primary Wave Music. Nearly seven years after Russell’s death at age 74, the LP is part of an effort by his survivors and stewards to bring attention to the work of a musician who bridged styles and eras — from rock and pop to country and gospel, from the ’60s song factory to the emergence of the ’70s auteur — but whose legacy has been overshadowed by those of the classic-rock icons he inspired and worked with, among them George Harrison, Elton John, Eric Clapton and Joe Cocker.

As an oft-top-hatted bandleader, Russell organized Cocker’s famously boisterous Mad Dogs & Englishmen and played a crucial role in Harrison’s all-star Concert for Bangladesh in 1971; he arranged horns for the Rolling Stones and played guitar and piano with Delaney & Bonnie and Friends, whose lineup Clapton borrowed to create Derek & the Dominoes. John has called Russell’s barrelhouse piano playing the model for his own, while acts as diverse as the Carpenters (“Superstar”) and George Benson (“This Masquerade”) scored huge hits with his elegantly crafted songs. In Russell’s music, history and geography fold in on themselves — you can hear New Orleans, L.A., his native Tulsa, Okla. — even as he showcases an instinct for the explosive and the unpredictable.

Can you think of someone else who worked with both Barbra Streisand and the Gap Band?

“Leon had the total package,” says Collins, the funk pioneer who played bass with James Brown and Parliament-Funkadelic and who teams with the art-rock group U.S. Girls for a slinky version of “Superstar” on the new tribute album. “Whether he was recognized as a bluegrass player or a rock ’n’ roll player or a jazz player, to me it don’t really matter much. And I don’t think it mattered to him. Certain things just touch the soul.”

Read more: Our expert picks for fall's can't-miss albums, concerts and music books

Often described as a musician’s musician — and by even those who admire him as curmudgeonly — Russell managed to dent the charts under his own name with songs like 1972’s rollicking “Tight Rope,” which made it to No. 11 on Billboard’s Hot 100. But by the time John cold-called him to make a 2010 duo album, he’d fallen — thanks to health and money troubles and to some dubious creative decisions — into what he called “a ditch by the side of the highway of life.” He married twice, abused drugs and booze and food and blew up a relationship with singer Rita Coolidge, she says, because of his taste for orgies; some claim that Russell cut Coolidge out of a songwriting credit for "Superstar" as revenge.

Now things are happening to elevate his standing. Bob Dylan, who recruited Russell in the early ’70s to produce a handful of tunes including “Watching the River Flow,” name-checks him in a cut from his most recent studio LP, “Rough and Rowdy Ways.” An exhaustive biography by author and musician Bill Janovitz, “Leon Russell: The Master of Space and Time’s Journey through Rock & Roll History,” was published to acclaim this past spring, just about the time Russell was feted with a tribute concert at Nelson’s Luck Ranch during March’s South by Southwest festival in Texas. And on the heels of “A Song for Leon,” a documentary project about Russell is said to be in the works with the involvement of big names yet to be revealed.

This Leonaissance comes as legacy acts’ catalogs have become newly valuable in the age of streaming and social media and of Hollywood and commercial licensing of old hits — see the resurrection last year of Kate Bush’s “Running Up That Hill” after it was featured in an episode of Netflix’s “Stranger Things” or the return of Fleetwood Mac’s “Dreams” to the Hot 100 in 2020 after a random TikToker used it in a skateboarding video. Primary Wave — which also owns portions of the intellectual property of Whitney Houston (whose 2022 biopic it helped produce), Bob Marley, Prince and Joey Ramone — acquired a stake in Russell’s music publishing and master recording income stream in 2019.

“I think of this tribute album as a trailer to the rest of what’s unfolding with Leon,” says Primary Wave’s Laurel Stearns, who assembled “A Song for Leon” and who describes Russell as “a genre-hopping genius.” Adds Dub Cornett, a veteran manager and producer who serves as a partner to Russell’s widow, Jan Bridges, in overseeing Russell’s estate: “It’s vital we keep his memory alive, reintroducing his music to a new generation.”

Read more: Meet Chappell Roan, L.A.'s queer pop superstar in the making

The eclectic nature of Russell’s career — he also co-founded Shelter Records, which released early singles by Bob Marley and by Tom Petty's first band, Mudcrutch — might make it easier to do that at a moment when young listeners think little of stylistic barriers. “A Song for Leon” certainly demonstrates the breadth of his approach and influence, with laidback alt-country from Price (who sings “Strangers in a Strange Land”), windswept balladry from Peck (“This Masquerade”), fuzzy indie rock from the Pixies (“Crystal Closet Queen”), trippy blue-eyed soul from Rateliff (“Tight Rope”) and swaggering R&B from Russell’s daughter Tina Rose, who teams with Nelson’s daughter Amy Nelson and Louis XIV’s Jason Hill for “Laying Right Here in Heaven.”

“His songs were all over the place,” says Rateliff, who took on “A Song for You” at Nelson’s recent 90th-birthday bash at the Hollywood Bowl. “But he had such a unique voice” — high, scratchy, perpetually lagging behind the beat — “and such a funny emphasis on certain sounds and words that it was always just totally Leon.”

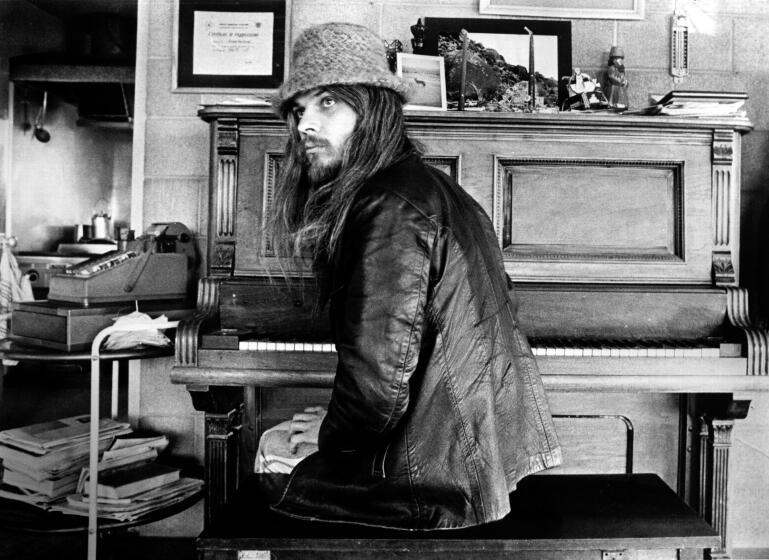

So too might Russell’s out-there look attract interest, just as it did back in the ’70s, when Jim Henson reportedly based his Muppets character Dr. Teeth on a combination of Russell and New Orleans’ Dr. John.

The Pixies’ Joey Santiago remembers glimpsing his older brother’s copy of 1974’s “Stop All That Jazz” — it’s got Russell with his trademark flowing white hair surrounded by a group of men in crude tribal dress — and wondering, “Who is this guy? Those dark eyes were made out of coal, man — just absolute rock ’n’ roll.”

Despite his obvious fondness for image-making, Russell’s semi-forgotten status is in part the result of his own ambivalence regarding stardom.

“Basically, he wasn’t tripping about himself,” says Collins, another experienced sideman with an outré appearance. Janovitz, who says he “can’t imagine Leon would have welcomed somebody writing a book about him," traces that aversion to fame to a traumatic childhood experience in which an aunt caught a 4-year-old Russell and a female cousin examining their differing body parts, then excoriated him in front of the rest of his family.

“That incident has affected me for my entire life,” Janovitz quotes Russell as writing in an unfinished memoir. “It has had an immeasurable detrimental effect on my career in show business in that I tend to freeze up around any situation that involves people watching me.”

Yet decades later he also seemed to relish confounding the music industry’s expectations, as in his eager experimentation with new synthesizers and drum machines — check out 1978's slick, disco-kissed "Americana" — and his decision to adopt an alter ego, Hank Wilson, to make old-school country records. He continued to record and tour in the ’90s and early 2000s to decreasing notice until John recruited him for “The Union,” which they cut with producer T Bone Burnett — and which provided the momentum to get Russell inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in 2011 (albeit through the side door of an award voted on by hall insiders as opposed to the full electorate).

According to Stearns, Russell’s estate was in a state of benign neglect — “His socials were so low,” she says — before Primary Wave got involved along with David Zonshine, a longtime music-industry figure who currently runs Harrison’s Dark Horse Records. Cornett says Dark Horse is planning a series of reissues of Russell’s albums and is exploring “the extensive audio archive that Leon left behind”; tantalizingly, Stearns adds that the archive includes “recordings with Leon and Willie that no one’s ever heard.”

What we won’t see anytime soon, Stearns promises, is anything that runs counter to Russell’s spirit just to make a buck. “So much of this stuff is really embarrassing,” she says of the suddenly booming rock-nostalgia market. “It’s not like we’re gonna do a Leon slot machine in Las Vegas.”

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.