Les Paul Innovation Award recipient Peter Frampton on talk boxes, teen stardom and why he'll 'never stop thanking' David Bowie

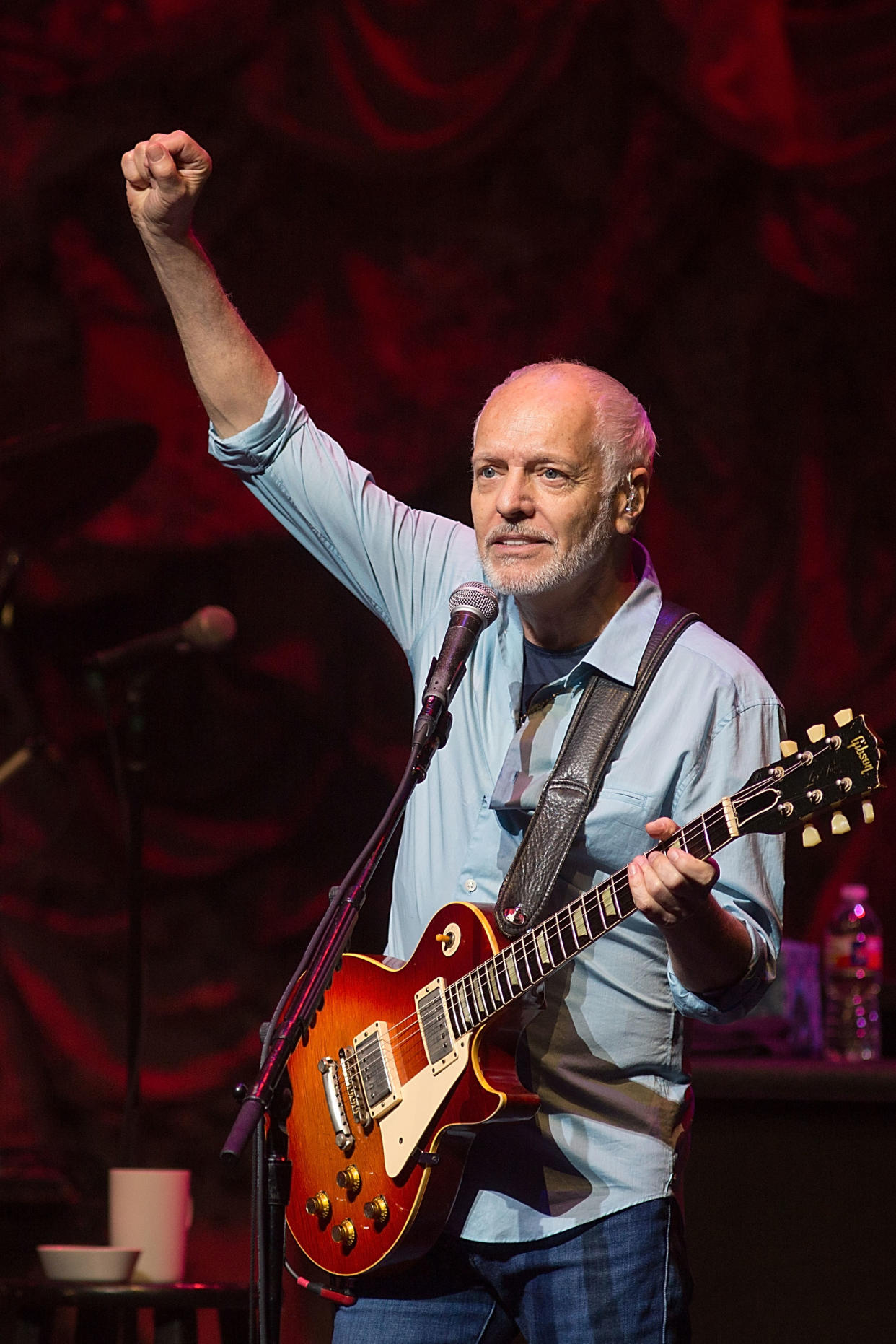

On Jan. 26, rock legend Peter Frampton will receive the Les Paul Innovation Award at the 34th Annual NAMM Technical Excellence & Creativity Awards in Anaheim, Calif., joining an elite hall of fame that includes past honorees Jackson Browne, Joe Perry, Don Was, Slash, Todd Rundgren, Pete Townshend, Steve Vai, and Lindsey Buckingham. Considering that Frampton, now 68, has been playing since he was 7 years old, joined his first band at age 12 and has reinvented himself repeatedly throughout his illustrious career — and was named one of the 100 greatest guitarists of all time by Rolling Stone — the accolade seems long overdue.

“Oh, well, I don’t know about that,” Frampton says humbly. “I’m just thrilled that I’m being put in that category of the other honorees.”

It hasn’t always been an easy road for Frampton. He struggled with the stigma of being a reluctant teeny-bopper star; suffered a near-fatal car accident; bore the brunt of the backlash surrounding 1978’s box office bomb movie musical, Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band; and found himself in a late-’70s career slump after his overeager record label rushed out a follow-up album to capitalize on his phenomenally successful double concert album, Frampton Comes Alive! But over the years, this true survivor has maintained his guitar-god status through his solo material, his work with his past bands and his collaborations with everyone from George Harrison to his childhood schoolmate David Bowie.

Ahead of this month’s NAMM ceremony, Frampton speaks with Yahoo Entertainment about the incorporation of the talk box into his signature sound, his attempts to distance himself from his teen-idol image and how his old friend Bowie helped him reboot his career. One thing he doesn’t speak about too much? That Sgt. Pepper movie, of course. But you can’t say we didn’t try.

Yahoo Entertainment: Congratulations on your award. Frampton Comes Alive! was your big solo breakthrough, selling 8 million copies in the U.S. alone, but you’ve experienced so many career highs — and lows — before and after that. You’re back in a great career period now, but what do you think went wrong after the live album?

Peter Frampton: I think that there would have been a lot to be said for not releasing the follow-up album. That’s my main thing that I always say. We didn’t need to release I’m In You for a good three, four years. …Everybody rushed me. I was young, 25 or 26, and I was indebted to everyone, I thought, around me who knew best, because they had handled big artists before. But to be honest, I was the only person that knew, because no one had been where I was. It was the biggest-selling album of all time when it came out. I was the biggest act in the world, and the old rules kind of go out the window there. You’re only as good as your last record, so don’t release one until it’s good — and that adage wasn’t followed. And I think the combination of the [Sgt. Pepper] movie and that was the reason for the downfall, definitely.

When you teamed with David Bowie in the mid-’80s to play guitar on his Never Let Me Down album and Glass Spider tour, was that when you felt things start to turn around for you?

It was, definitely. I had not been touring in the ’80s — I had stopped in like ’82, I think — and David called me up. We went to school together, and we had been friends ever since then. He said, “I love your new record. Come and play some of that guitar for me on my next record.” I said, “You’re kidding me! It took you long enough!” So yeah, I went and did the record, and then while I was in Switzerland where we were, he asked me to do the Glass Spider tour, and it took me about two-tenths of a second to say yes. … We had such a long history together, and it was a giant gift he gave me. I’ve never stopped thanking him, and I still do to this day.

He knew what had happened. He saw me, the musician, because he knew me, Peter, the guitar player. He didn’t know Peter the teeny-bopper star. So when he saw all that happening to me, and there was a major downswing in my career, I think that’s when he realized that “people need to know the truth about Peter.” He could have chosen anybody [to play guitar for him], but he called me. He took me around the world in stadiums and reintroduced me as the guitar player. You can’t thank someone enough for that, especially David. It was definitely a turning point for me.

You and David Bowie attended the Bromley Technical School together and played in bands there — you with the Little Ravens, and Bowie with George and the Dragons. Please tell me there’s some footage out there of you two jamming together on Buddy Holly songs when you were 12 years old!

No, there isn’t — but we did! [Laughs] But there’s footage of us walking around, I think somewhere in Spain, looking for a beer. That’s on the internet.

Since we’re talking about going back to your school days, when you were just starting out, what’s your first memory of picking up a guitar?

It was actually a banjolele — a ukulele shaped like a banjo. It was my grandmother’s. She gave it to my dad [Owen Frampton, who was Bowie’s art teacher] and said, “Put this somewhere where Peter finds it.” So I found it, and I said, “What’s this, Dad?” And he said, “It’s a banjolele. Your grandmother thought you might want to try it.” … I was about 7, and he started to teach me “(Hang Down Your Head) Tom Dooley” and “Michael, Row the Boat” and “She’ll Be Coming ‘Round the Mountain (When She Comes).” I learned those very quickly, and then before I was 8, that Christmas I asked for Santa to bring me a guitar; I still believed in Santa. The guitar was at the foot of my bed when I woke up on Christmas morning — and I saw “Santa” leave the room, and I knew it was Dad. It was kind of bittersweet: Yes, I got a guitar, but Santa isn’t real, he’s Dad! [Laughs]

Did you take to the guitar right away?

Well, I said, “Dad, there’s six strings on this. How do I tune the other two?” Because a banjolele, or ukulele, only has four. So he tuned it for me and said, “Now go away.” And that was it. I’m not sure if they were thrilled afterward that they gave it to me or not! But it was the beginning of where I am today.

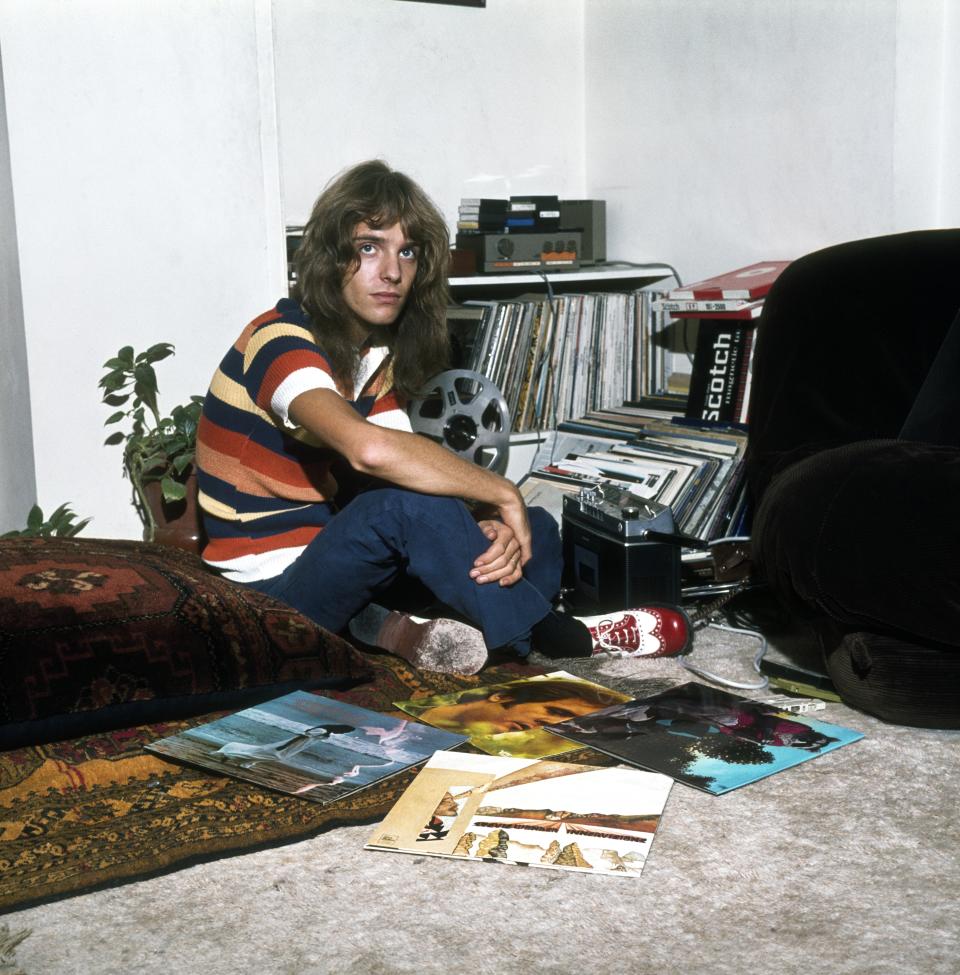

I know that when you were in the Herd at age 16, but then at age 18, you left that band to form Humble Pie, because you didn’t want to be a teen idol. Do you think because of your good looks that you were unfairly stuck in that category at times, and thus your guitar skills were overlooked? You were definitely a teen idol in the late ’70s.

Well, it’s always been about the music for me. My looks have obviously helped along the way, there’s no doubt. My success, I feel, is more built on the material than the looks — but it didn’t hurt, I’ll put it that way! [Laughs] But having been part of a teeny-bopper situation when I was 16, 17, and then I got out of that and formed Humble Pie with Steve Marriott … we basically went anti-pop star with that situation. Because Steve was screamed at [by teen fans]. I was screamed at. And we didn’t want to get screamed at! But we released our first single in England, “Natural Born Boogie,” and we went on Top of the Pops, and guess what? We got screamed at!

So we basically packed up, left and went to America, where we wanted to be accepted. We weren’t known as much there. … So when we got to America, we were bottom of the bill, and we built our reputation for what we sounded like on nothing else. There was no history, no baggage, and it worked. And then when I left Humble Pie, at that point, again it was going back to, not all the way down the ladder, but I was a couple of rungs from the bottom again, starting up once again. Obviously when I started to have success, I didn’t look too bad to the women. It was overkill. It’s one of those things where it took off, and there’s almost no controlling that.

Since you are receiving this Les Paul award for guitar innovation, I would be remiss if I didn’t talk to you about the talk box, which is such a part of your signature sound. Obviously, I know you weren’t the first to do it — but a lot of rock fans, when they think of talk box, they think of you. How did you first discover it?

Well, when I was in my very formative years, when I was 12, 13, something like that, there was radio station that beamed out from Luxembourg in Europe, and we could actually pick it up. It would fade in and fade out, but it was the only place we could hear great American music, because the BBC wasn’t thrilled with pop music as much as we were. We only had one channel, and it played everything. So this station every night used to have a call sign, and there’s another gadget that’s very similar to the talk box that you put on your throat. … So I heard that sound, that computerized sound, very early on, and then I listened to “Music of My Mind” by Stevie Wonder, and he was using a throat box, and I said, “There it is. There’s that sound again.”

I started to look around, and before I actually found one, I was in Abbey Road Studios with George Harrison doing All Things Must Pass, and that’s when Pete Drake, the Nashville No. 1 pedal steel player, was sitting right opposite me. In a slow moment, he got out this little box with a pipe and wires and plugged things, and we didn’t know what he was doing. He said, “Let me show you this,” and then the pedal steel started singing to us out of his mouth, and it was the sound of the pedal steel with that talk box sound. There’s actually audio of George talking, we’re all standing around him, and there’s actually audio online of us saying, “Oh, wow!” You can hear because they ran tape while he was demonstrating. It was a Eureka moment for me, and I just went, “Where did you get that?” He said, “I made it myself.”

That’s when I finally was back in America for a while, and my girlfriend went to [sound and radio engineer] Bob Heil, who was now making these talk boxes at the direction of Joe Walsh, who used a talk box on “Rocky Mountain Way” — which I still believe is the definitive talk box solo without actually talking; I think it’s one of the best solos out there. So anyway, I got given one for Christmas, must’ve been in ’72, ’73. And by the time we next toured, I was already using it. I had introduced it into “Do You Feel,” and the first time I used it, the crowd kind of moved forward about six inches. I felt I pulled them in, and they went berserk — because it was not something you’d heard at that point.

Since you mentioned George Harrison — I know that the Sgt. Pepper film has gotten a lot of flak over the years. And you seemed to get it the worst, for some reason. But that movie introduced me and a whole generation to the Beatles. I’m not kidding you: For some kids, that movie was a gateway into rock, or even into music in general.

Well, that’s the first plus I’ve heard for that movie coming out!

Ever? Really?

Ever. I know, I know, I shouldn’t put it down. It’s just that it wasn’t good for me. So obviously, it’s not something that I cherish when it comes on TV every year.

Your fondness for the movie hasn’t grown at all in the past 40 years?

No. I’m not going to talk about Sgt. Pepper. I’m sorry. You can say what you want, but it’s not something I wish to talk about.

I understand. I just want to let you know that when it comes on TV that I do watch it.

Well, thank you. [Laughs]

Read more from Yahoo Entertainment:

Follow Lyndsey on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Google+, Amazon, Tumblr, Spotify