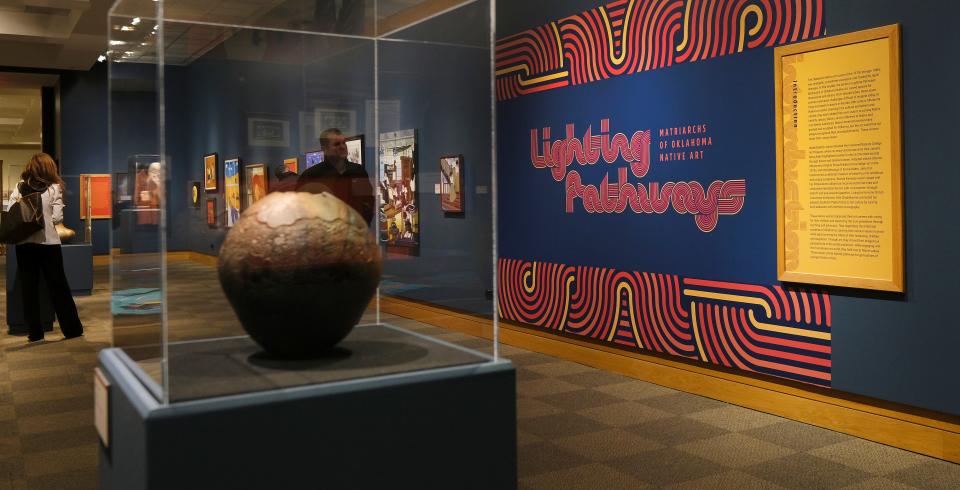

'Lighting Pathways': National Cowboy Museum spotlighting 'Matriarchs of Oklahoma Native Art'

To honor the "Matriarchs of Oklahoma Native Art" who have been "Lighting Pathways" over the past four decades, an exhibition at the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum is digging into the past.

In the 1970s, contemporary Native art began to surge in popularity, as major museums organized exhibitions, the Cherokee Heritage Center near Tahlequah launched its prestigious Trail of Tears Art Show, and the Institute of American Indian Arts was founded in Santa Fe, New Mexico.

But something was missing from the movement.

"You might see Harry Fonseca or you might see T.C. Cannon or Fritz Scholder. But, like today, the art field was very dominated by male artists," said Tahnee Ahtone, a Kiowa, Seminole and Muscogee curator.

"The female artists, they were still having to maintain their day jobs, they were still maintaining to be parents, and also to have an art career. And there was a very strong influence within galleries in the market to pay the female artists less than their male peers ... even though the women were creating just as elaborate art."

So, her aunt Virginia Stroud, a Keetoowah Cherokee and Muscogee painter, helped organize in 1985 the groundbreaking traveling exhibition "Daughters of the Earth." Featuring works by eight Oklahoma Native American women artists, the exhibit launched in Oklahoma City on a three-year tour across the country, according to The Oklahoman Archives.

The National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum is celebrating the "Daughters of the Earth" trailblazers, along with three of their fellow Oklahoma Native women artists, in its exhibit "Lighting Pathways: Matriarchs of Oklahoma Native Art."

"They had an impact on the Native American art movement across the country (as) Oklahoma is the heart of Native America," said Eric Singleton, the museum's curator of ethnology. "It was really important to put these artists in a place where people could see their work again — and see it in the context of the individual artists and not some larger show. It's just about them."

'Lighting Pathways' pays tribute to living Native women artists from Oklahoma

On view through April 28, "Lighting Pathways" is paying tribute to seven living women who overcame significant challenges and emerged as influential artists in the late 20th-century Oklahoma Native American art scene. It is curated by Ahtone and America Meredith, who is Cherokee.

The exhibit features works by Stroud; her sister, Sharron Ahtone Harjo, who is Kiowa; Mary Adair, who is Cherokee; Allie Chaddlesone, who is Kootenai; Ruthe Blalock Jones, who is Shawnee, Delaware and Peoria; Brenda Kennedy, who is Citizen Potawatomi; and Jane Osti, who is Cherokee.

Although some of the artists featured in the 1980s exhibit have died, Jones, Adair, Ahtone Harjo and Stroud were part of "Daughters of the Earth."

"This is to remind the arts community that these women contributed in this way, during a time period that many of us have probably fallen asleep on. ... Back then, there really wasn't a living time stamp on them that lived on the internet or within archives. Even though we share these memories with one another in the community, we wanted to make sure that we still celebrated them," said Tahnee Ahtone, the daughter of Ahtone Harjo.

"We included Brenda Kennedy, along with Allie Chaddlesone ... and Jane Osti, for their contributions as somewhat the generation following the 'Daughters of the Earth.'"

For Ahtone Harjo, "Lighting Pathways" has reignited her 40-year-old memories of "Daughters of the Earth."

"At that time, things were lacking in the way of promotion for Oklahoma artists, so we got on a bandwagon Virginia started. ... We're all really pretty close friends and relatives now," Ahtone Harjo said.

"To be included in something such as this is special. ... I have lived in the Oklahoma City area since The Cowboy first opened — and that was a long time ago. I've seen it grow and grow and grow, and it's good to see the Native things here. It's been here, but sometimes you couldn't see it as visibly as (you can) now."

Here's what to know about the seven artists included in "Lighting Pathways: Matriarchs of Oklahoma Native Art:"

Sharron Ahtone Harjo (Kiowa)

Kiowa artist Sharron Ahtone Harjo, also known as Marcelle Sharron Ahtone Harjo, has devoted her career to reviving and ensuring the continuation of ledger art, a Native narrative pictorial style of painting on paper or muslin. She and her adopted sister, Virginia Stroud, were instrumental in bringing back ledger art in the 1970s with encouragement from Kiowa elders and their teacher, Cheyenne artist Dick West, at Bacone College.

Ahtone Harjo's grandfather, Samuel Ahtone (1864-1949), was a Kiowa ledger artist, and she studied his ledger book and calendars growing up. Her great-grandmother Millie Durgan Goombi, a captive adopted into the Kiowa Tribe, was a master cradleboard maker. Ahtone Harjo inherited her Kiowa name Sain-Tah-Oodie, which translates to "Killed With a Blunted Arrow," from Durgan Goombi.

After graduating from Bacone, she served as Miss Indian American 1965 and earned her bachelor's degree from Northeastern State University in Tahlequah. In 1978, she helped establish the Center for the American Indian in OKC.

The Oklahoma City resident is also a longtime arts educator who taught in many schools nationwide, including at the Concho Indian Boarding School before taking a position in Edmond Public Schools. She was honored at the 2024 Oklahoma Governor's Arts Awards as one of five recipients of the Arts in Education Award.

Virginia Stroud (Keetoowah Cherokee/Muscogee)

Virginia Stroud, who is Keetoowah Cherokee and Muscogee and lives in Tahlequah, is considered one of America’s foremost female contemporary Native painters.

Born in California, she was just 11 when her mother died, and the future artist moved to Muskogee, where she studied at Bacone. Jacob and Evelyn Ahtone (Kiowa) adopted Stoud, and she and her adopted sister, Ahtone Harjo, were key in reviving ledger art in the 1960s and '70s.

The Cherokee tear dress was invented in 1969 for Stroud to wear as Miss Cherokee and popularized when she was crowned Miss Indian America.

Mary Adair (Cherokee Nation)

Cherokee Nation artist Mary Adair, who lives near Sallisaw, was born on her grandparents' Oklahoma allotment and immersed in Cherokee history by her relatives. She started in oils and then moved to watercolors, creating her version of the flatstyle painting that West taught her at Bacone. In the first art show she ever entered, the 1967 Philbrook Indian Annual in Tulsa, she won a prize.

Teaching and mentoring youth took precedence over her own art career, but she has exhibited her work throughout Oklahoma and nationwide. Along with painting, Adair has crafted moccasins, shawls and finger-woven sashes for her family and other Cherokee youth, eventually winning in New Mexico a Santa Fe Indian Market award for fashion.

Brenda Kennedy (Citizen Potawatomi)

Citizen Potawatomi artist Brenda Kennedy, also known as Brenda Kennedy Grummer, is arguably best known for her naturalistic acrylic paintings of powwows but has experimented with many styles.

Raised on a farm in the Cheyenne and Arapaho nation, she graduated from Southwestern Oklahoma State, where she met her husband, Ken Grummer, who's encouraged her throughout her art career.

She reconnected with her Potawatomi community as a young adult and attended dances in Shawnee and throughout the state. She's won numerous awards, including the Grand Awards at the last Philbrook Indian Annual in 1979. Her work is in several public collections, including the Citizen Potawatomi Nation Cultural Heritage Center.

Jane Osti (Cherokee Nation)

Cherokee Nation potter Jane Osti, of Tahlequah, creates utilitarian vessels as well as more experimental and sculptural works. She has always combined Cherokee and Southeastern iconography with her observations of the natural world and geometric abstractions. She hand-coils her clay forms, which she can fire outdoors or in a kiln.

Receiving almost no art education in rural Oklahoma, where she grew up, Osti discovered art in California and returned to the Cherokee Nation to earn a master's degree in art from Northeastern State University. Osti apprenticed with Cherokee Nation artist Anna Bell Sixkiller Mitchell, who revived ceramics among Oklahoma Cherokee, and in turn taught subsequent generations of ceramics artists.

The Cherokee Nation named her a National Treasure in 2005.

Allie Chaddlesone (Kootenai)

Adeline "Allie" Chaddlesone did not know of any women who sculpted in stone when she became an artist, but she watched men carve stone and knew she could do it, too. She not only taught herself to carve stone but also quarried her own alabaster near Anadarko.

Born in Ktunaxa territory in British Columbia, Chaddlesone grew up in the Kalispel Reservation in Washington. Kalispel was her first language. She studied modern dance and two-dimensional art at the Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe, where she met her husband, Kiowa artist Sherman Chaddlesone (1947-2013).

At first, she painted and experimented with ceramics, but she taught herself to carve stone in the 1980s and has exhibited in Oklahoma and across the country.

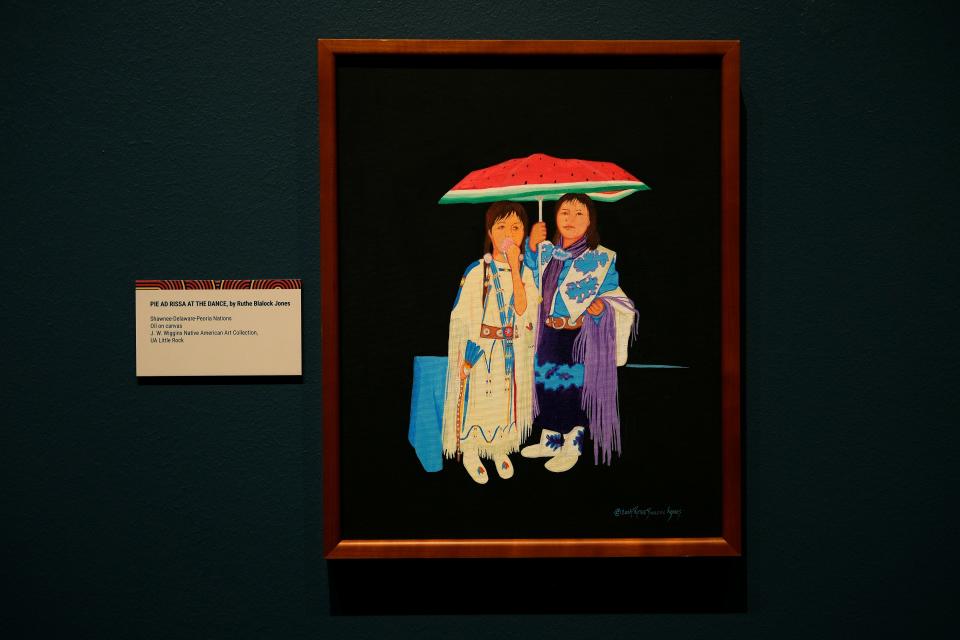

Ruthe Blalock Jones (Shawnee/Delaware/Peoria)

At age 13, Ruthe Blalock Jones, who is Shawnee, Delaware and Peoria, first entered a painting in the Philbrook Indian Annual in Tulsa. Her painting won an award, and famed Muscogee artist Acee Blue Eagle purchased it, launching her career as a painter and printmaker. Her graceful figurative works evolved from the heavily contoured Bacone school style.

Her traditionalist full-blood parents spoke their tribal languages and encouraged her to participate in Shawnee ceremonies, stomp dances, Native American Church meetings and powwows. Charles Banks Wilson was an early mentor, and Jones studied art under West in high school and at Bacone. She later earned her master's degree at Northeastern State University. From 1979 to 2009, she served as the first Native woman director of Bacone's art department.

Born in Claremore, Jones is an internationally known artist, educator and art historian and was named the 2011 Honored One at the Red Earth Festival. She lives in Okmulgee and has exhibited her work on four continents.

'LIGHTING PATHWAYS'

When: Through April 28.

Where: National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum, 1700 NE 63.

Tickets and information: https://nationalcowboymuseum.org.

This article originally appeared on Oklahoman: National Cowboy Museum spotlighting 'Matriarchs of Oklahoma Native Art'