Linda Ronstadt Talks Heritage, the Immigration Crisis, and Joni Mitchell

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through the links below."

“There’s been prejudice against Mexico ever since the United States stole it in 1846,” says Linda Ronstadt. “We forget that Arizona, New Mexico, Utah, California, they were all parts of Mexico. It’s a huge swath of land, and it was taken unfairly by the Americans. So, the Mexicans who stayed didn't migrate—the border migrated.”

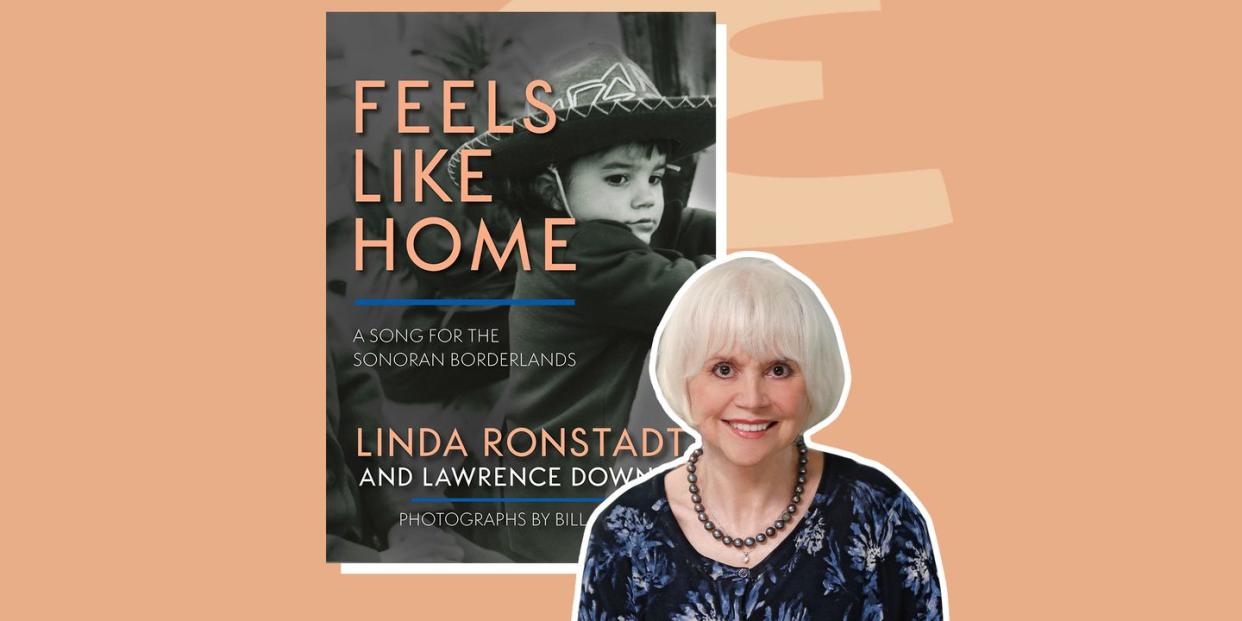

The Rock and Roll Hall of Famer, granddaughter of Mexican immigrants and descendant of Spanish settlers, explores her family history and the complicated relationship between the US and Mexico in her new book, Feels Like Home: A Song for the Sonoran Borderlands. Co-written with former New York Times editor Lawrence Downes, it’s filled with traditional Sonoran and southern Arizona recipes, traditional song lyrics (there’s a companion playlist), and evocative photos by her friend Bill Steen.

But this territory isn’t new for Ronstadt; it’s something she’s consistently been examining at least since her groundbreaking 1987 album Canciones de Mi Padre. A collection of traditional Mexican songs was an unprecedented move for a star of her stature at the time, but it went on to become the biggest-selling foreign language album of all time and was followed up with two more albums of Latin music, Mas Canciones and Frenesi.

She wrote about her family in her 2013 memoir, Simple Dreams, and after her 2019 Grammy-winning biographical documentary The Sound of My Voice, she released a companion film, Linda and the Mockingbirds, which chronicled a trip she took with a busload of schoolchildren to the small Mexican town where her grandfather was born.

All this work, of course, has come during a time of increasing tension and political grandstanding over immigration. But Tucson-born Ronstadt points out that her own roots run deep in both countries. “My family has been very happily existing on both sides of the border since the early 1800s,” she says, on the phone from her home in San Francisco. “Actually, longer than that, because the original ancestor came in the 1500s. We've been there longer than anybody but the native Mexicans, the Native Americans”

What you might never know from reading Feels Like Home is that Linda Ronstadt was one of the biggest rock stars of her time, selling more than 100 million albums and winning 12 Grammy awards. Considered by many to have the best pure voice of her generation, her work was staggering in its range, encompassing everything from country to American standards to light opera, in addition to introducing many listeners to such songwriters as Warren Zevon and Elvis Costello.

Yet she shrugs off her fame and even the caliber of her singing. “I always had a real problem with phrasing,” she says. “I don’t like the way I phrase a lot of stuff. I hear my records and I go ‘Oh, my God, I can't believe I did that.’ “

Ronstadt, 76, announced her retirement in 2011 and revealed shortly afterwards that she is no longer able to sing as a result of Parkinson’s Disease; she was later re-diagnosed with a similar condition, progressive supranuclear palsy. But in the book and in conversation, her continuing love for the music and culture she grew up with shines through.

“I've been singing since I was three,” she says. “So, some of these Mexican songs are deeply personal for me, sacred to my family. We had a picnic, a pachanga we call it, where you cook outside and sit outside. And my family was there singing, four or five generations, and we all still do the same songs.

“I can't sing at all anymore, my voice has tanked. But we’ve got a lot of different good voices in the family, from soprano to bass. And when they sing, I have to put on a harmony—even if it’s just in my brain, I hear where I fit.”

Esquire: You've revisited the history of your family and of the Sonoran region multiple times. Why is it important to you to continue to tell this story?

Linda Ronstadt: Because people need to know what it's like in Mexico. They need to know what the people are like. They're extraordinary in this particular valley. An American cowboy who wants to be a rancher buys 1000 acres of land, but out in the middle of nowhere, and they're not part of a community. Their life is lonely, kids are bored, whatever. They don't get to see other people unless they drive miles into town. But in Mexico, they make a village, and they share the grasslands. You help each other with everything you do—if your roof needs fixing, or you need a new house put up, your neighbors will all help you. It's a very cooperative society, and it’s been kept away from other evil things. If you get a flat tire, someone will pull over and help you and take you an hour away to buy a tire and back. But if you break down on the California freeway, they’ll run over you.

The Canciones de Mi Padre album was such a pivot point in your career and your relationship to your heritage. How difficult was it to get that record made and what did it mean for you to do it at the time?

The record company, of course, didn't want the record. And my manager thought I was committing career suicide. They just couldn’t hear it, it was like birds chirping in the wind, but I could hear the music. So I set myself to learning the music up to a better standard.

My manager, Peter Asher, to his credit really got behind me. He thought I was crazy, but he produced the album, and he did a good job. And same with my record company. They went along with it. I’d made a bunch of hit records, and the record I made with Nelson Riddle [What’s New in 1983, the first of a trilogy with the legendary arranger] wasn't supposed to be a hit and it was, so I’d earned the right. I just went into the studio and started cutting old Mexican songs—it seemed perfectly logical to me!

In the book, you write powerfully about going to visit refugee centers and migrant camps. We're back in an election season with a lot of focus around immigration issues. What do you hear in this latest version of that debate?

Well, put it this way: I've read quite a lot of German history, especially around the Weimar Republic, and when the person who used to be President came down his escalator—so grandiose and so stupid—and said that Mexicans were rapists and murderers, I thought, this is the Weimar Republic, he’s Hitler and the Mexicans are the new Jews. He’s taking advantage of people that are ignorant and don’t know any better and convincing them that Mexico is responsible for their problems. That’s why they can’t get a date, or they failed to go to school so they can only earn substandard wages.

You’ve seen this your whole life. Is it anything new, or is it just a game plan that still works?

That game plan works like a charm. But we're all just people, we have the same needs and desires, to live and thrive. There's been a drought in Mexico, a terrible drought like we have in California. People are desperate. Nobody really wants to leave their home unless they live in a floodplain. They don’t want to leave their home and their family and their friends and come to a strange place that’s hostile to them. That's not the attraction. The attraction is, I need to go north or I starve. I have to go and send money back to my family so they won't starve.

These last few years, there have been a number of documentaries and books about the Laurel Canyon scene where you started. Did you watch any of those?

I didn't see the Laurel Canyon one. I don't know what streaming channel to get it on. I didn't have a TV for 30 years. and finally, when President Obama was elected, I said “I have to get a TV so I can see his speeches without having to go to a friend’s house to watch.” I don't know how to work a television—I think you have to get a 13-year-old for that.

Why do you think there’s still such a fascination with that place and time?

I think people like their grandparents’ music. I liked my grandma’s music. It might be genetic, I don't know. I think there was a lot of quality that came out of the Laurel Canyon scene. Neil Young and Crosby, Stills and Nash. Joni Mitchell by herself would have put it on the map.

Did you see Joni’s performance at the Newport Folk Festival?

I watched it on YouTube. She’s obviously vocally impaired, but she’s still a great singer, still a great songwriter. I liken it to a ruin, a beautiful ruin. In her position, I wouldn’t have done the same thing, but I understand why she did. It was inspiring to see generations of kids up there with her, all influenced by her music.

In interviews and in your books, you often seem reluctant to talk about your own celebrity and success.

Most important is the work. I know what I did well and what I didn’t do as well. The rest is just noise in the background.

You Might Also Like