Lionel Richie: Writing “We Are the World” Was a “Train Wreck in My Head”

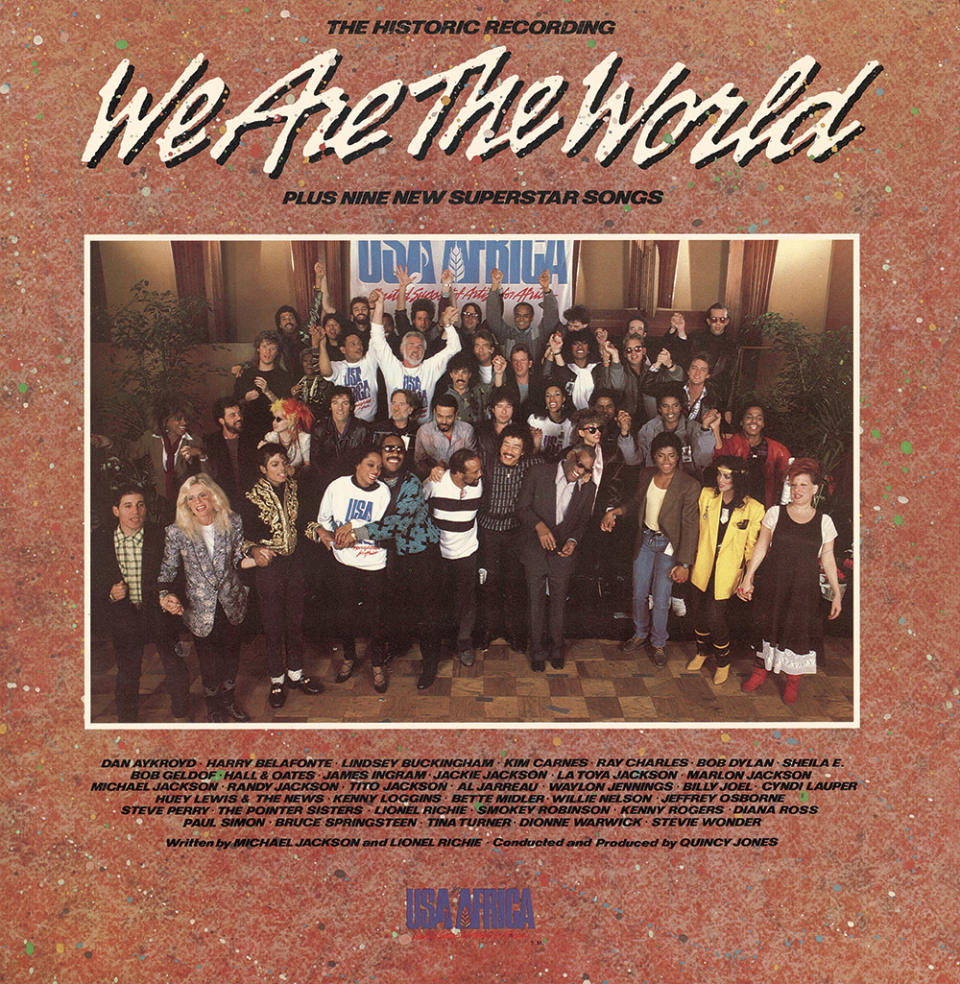

As a global pop culture event, it’s hard to match the release of “We Are the World,” the charity single that sold more than 20 million copies in 1985 and united 46 musical stars as enormous and disparate as Michael Jackson, Bruce Springsteen, Bob Dylan and Diana Ross at an all-night secret recording session. The story of that night — the scrambling, the egos, the moments of creative kismet — is now told in Bao Nguyen’s documentary The Greatest Night in Pop, which will premiere Jan. 19 at Sundance before streaming on Netflix beginning Jan. 29.

“When I heard how they assembled the team, to me it was almost like a heist film,” says Nguyen, who directed the 2020 Bruce Lee documentary Be Water. “You have Quincy Jones as the Danny Ocean of the whole effort. And they’re assembling [the team] — who’s the best rock star, who’s the best legend? There’s a bit of a ticking time bomb structure to what was, essentially, the making of one song.” Archival producers combed through some 50 hours of footage that had been shot for a TV special, as well as audio recordings made by a Life magazine journalist who was there that night.

More from The Hollywood Reporter

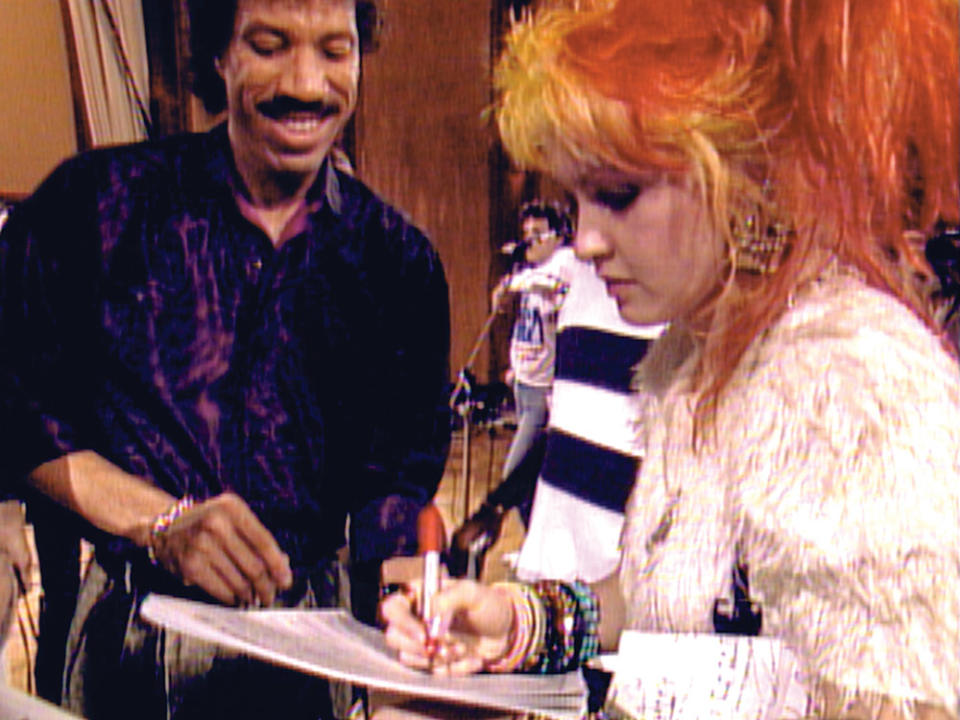

One of the key figures in the room was Lionel Richie, who co-wrote “We Are the World” with Jackson in a two-week sprint and served as producer Quincy Jones’ “floor man” during the recording session, troubleshooting and helping to keep his anxious peers on task. Richie, who was also hosting the American Music Awards that night, spoke to THR about the adrenaline-fueled process and the long-held mysteries of the night, like where was Prince and why does Dylan look so stressed? He also shares why you could never pull off a comparable talent coup in 2024, and why he considers the night they recorded “We Are the World” “the end of my innocence.”

Bob Geldof’s charity song to benefit the Ethiopia famine victims, “Do They Know It’s Christmas?,” came out a few months before you recorded “We Are the World.” Did that song help spark this one?

What it did was it opened the door. It set up the power of artistry. I got a call from [my manager, Ken] Kragen, saying, “Harry Belafonte’s looking for you.” Wonderful thing about back then, you could call somebody at 3 in the morning and they pick up the phone. When I called [Belafonte] back, there was one line he put in there that made it all come together. He said, “Black folks dying, Lionel. I need some Black folks to save them.”

Tell me about writing the song with Michael Jackson.

Kragen decided, well, everyone’s going to be in town for the American Music Awards. That’s the perfect place to have everybody do it. Great, except one thing. We didn’t know anything about that, me and Michael. So Kragen’s calling people and planning. And Michael and I are having the best time. We haven’t hung out together like this. I got a terrifying phone call on the second day of [meeting with Jackson], which is that [the other singers] are going to come the night of the AMAs. Kragen, that’s two weeks away! We don’t have a song. All we kept hearing was, “Well, we’re adding more people.” You’re adding more people to what? I would love to tell you we were focused. But this was like trying to get two 3-year-olds to sit down and focus. We were all over the place. We were down at the house and watching the dog argue with the bird — who could talk. Looking at the snake and Bubbles.

These are the Jackson family animals you’re describing?

These are Jackson family animals in the house. It was one big zoo inside, and hilarious. And we’re having the best time, except Quincy [Jones] is calling on the phone saying, “Guys, I need a song.” Meanwhile, at the same time, Dick Clark is sending me copy of what I’m going to say hosting the American Music Awards. By the way, I’m also going to open the show by singing. So now I have to rehearse with the dancers and the singers and the la, la, la. And it was one big train wreck in my head.

The caliber of artists who were all coming to sing a song you hadn’t written yet — was that energizing to you or paralyzing?

Let me explain to you my very sick MO. If you give me a whole semester to write a term paper, I will wait till the last five days and write the term paper. So the more it became clear that there’s a cliff at the end of the street, the more focused I got. I’m going to tell you how ADD works and ADHD works. You can’t leave it open-ended. You’ve got to give me a crash point, and then I’m there. I’m all there. So the two of us were la, la, la, la, la. Until we realized (imitating Jackson’s voice), “Oh my God, Lionel, this is going to happen next week.”

You referenced ADD. Do you actually have attention deficit disorder?

The answer is yes. And whenever I like to make an excuse for myself, I go, “Eh, this is what ADD does.” Now, it drives everybody else crazy because everyone else is spinning, going, “Is Lionel going to deliver this or not?” But it gives me an excuse to go, “Guys, it’ll happen.”

[With Jackson] everything was, “Oh my God, Lionel, what are we going to do now?” As we were putting it together, we were also thinking about how the words would last over a period of time. There’s no words in there like, “Right on.” Once you say “Right on,” you’re locked into the ’60s. If you say, “Yo, dawg,” you’re locked into the ’90s. So you can’t use anything hip or slick. It has to be really well thought-out.

As the performers entered the recording studio that night, you were all greeted by a sign that said, “Check your egos at the door.” Did that work?

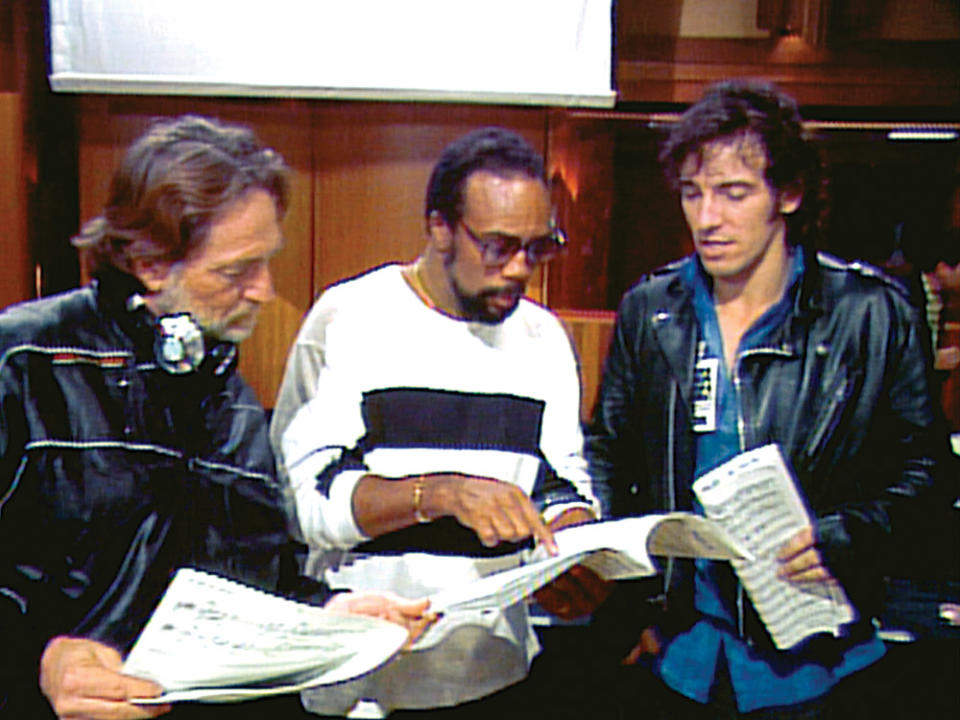

Quincy put that up. He’s the master of chaos. One other part of this whole equation: We have solos that are going to be done. Who does the solos and in what key can they sing? So [before recording], we had a meeting at my house and put a fan [of artists’ names] on the floor. We brought in [music producer] Tom B?hler. He has listened to everybody’s records and figured out what key everybody can sing in. “OK, Cyndi [Lauper]’s going to sing here, Lionel, you’ll start with Stevie [Wonder] down here.” There was one other point that got my attention. I said, “OK, are we going to bring them in the room one by one to put their parts on?” And Quincy said, “No, no, no. We make a half circle and we have them face each other.” I said, “You’re going to have everyone walk in the room, look at each other and sing their part?” He said, “That’s correct. We won’t have to worry about concentration. They’ll all be thinking.” Quincy said, “OK, now this is the only session in the world where you don’t ask the question, ‘What do you guys think?’ You have a room full of creatives. You’ll have 20 different arrangements of ‘We Are the World.’ You don’t ask Bob Dylan, what do you think? You don’t ask Bruce. You don’t ask Steve Perry, you don’t ask Michael, no one. Don’t ever say that.”

Bob Dylan looks so uncomfortable.

Poor Bob was having a nervous breakdown. He’s trying to sing it. And we said, “No, we don’t want you to sing it, just do it like Bob Dylan.” If you’re thrown in a room with a bunch of singers, you have a tendency to get psyched out, that you want to sound like them. But everyone that we chose as the lead vocalists, they were not singers, they were stylists. We only had half a line, and, in certain cases, one line to sing. We had to make sure that whoever was singing, your voice was identifiable right away. Now, Bob Dylan has an identifiable voice instantly. But he was trying to sing it another way. We kept saying, “No, just sing it like Bob Dylan.” But did you see that look on his face? He was like, well, what does that sound like?

As we see in the documentary, you had a solo in mind for Prince, who never showed up, and Huey Lewis ended up singing his part. Why didn’t Prince show?

That’s the 97 billion-dollar question. Knowing him, it just wasn’t in his, what should I say, his brand. At that time, he wasn’t a group person. He was Prince. The next thing is his rival, Michael. Do you want to stop the rivalry and join a group of people singing a song, standing next to his rival? No. I mean, from a strictly egotistical point of view, I could see it. Now, was he going to show up? It was 50/50. I knew where he was. Carlos n’ Charlies [a Mexican restaurant on the Sunset Strip]. I was hoping he was going to come by. But there’s a point when that tape starts rolling, that’s it. But that has always been my only thought. What if. I don’t quite know what that would’ve been.

What went into the decision to swap Huey Lewis in for Prince’s part?

Poor Huey, even to this day, he still hasn’t recovered. He did a great job. But the thing about it, every time we started rehearsing, we get halfway around the thing. We go past Michael, and once we get past Michael, we would stop because we had to go back and correct somebody else’s microphone or somebody else’s vocal part. So we never got a chance to go from Cyndi to Huey. And Huey was going, “Guys, can you do me a favor? Can you just run it one time ’cause I don’t know what I’m singing yet.”

This music video has yielded so many memes with people speculating about what’s going on in the artists’ heads, especially Michael when he’s looking at Huey. People think he’s unhappy with how Huey’s singing. Are you aware of the memes?

Absolutely. And I laughed through each one of them because every one of them is wrong. Think about the insecurity, the ego, all of that switching back and forth. You’re standing next to Ray Charles. I mean, no matter how famous you thought you were, you’re not as famous as Ray. That’s Diana Ross over there. It is only so much ego we’re going to bring to the room before you go, “OK, hold on. Let me organize my head here.”

How come we don’t see a charity single like this today? Are there barriers to doing something like “We Are the World” in 2024?

What made “We Are the World” so fantastic was we snuck up on the world. It came out fast. You could surprise somebody. And now people are jaded. They’re more interested in themselves being famous than in famous people. The internet made everybody famous. When we put out “We Are the World,” Michael and I were sitting there watching, and here they are singing in the streets in Paris, in London. Here they are in downtown New York, in Tokyo. It was a movement. I use “We Are the World” as my example of the end of my innocence, because from that point on, the world became too hip. The way to judge it is, if we had to do it today, could we do it between 1 o’clock and 7 in the morning after an award show? No. The next thing, put me together, one line per artist, and without looking at a photograph, tell me who that is singing. One line, half a line. Tell me who that is today.

Is that because artists today sound too similar to one another?

It’s a different era. Rap is very strong. And, by the way, rap has its signatures. If you listen to rap, I can tell you one rap artist from the next because they have a signature style. But when you start thinking about vocalists, OK, who are the vocalists? I can name five or six who have identifiable sounds. When I do American Idol as a judge, I try to tell them, “Forget about singing. Do you have a style in your voice?” Bruce Springsteen, he could hum the phone book and you know it’s Bruce. Tina Turner, you knew it was Tina. Voices were different-sounding from one to the next.

Have you seen any of the parodies of “We Are the World”?

Yes, I have. “Weird Al” Yankovic. I remember that one years ago. Which ones are you thinking of?

I was thinking of a Doonesbury cartoon where the character’s only line in the song is the word “the.”

I love it. People say, “God, I can’t believe they’re teasing you about this.” I go, guys, teasing is the best form of flattery because it means it’s popular. When they don’t talk about it at all, that’s when you have a problem.

This story first appeared in the Jan. 18 issue of The Hollywood Reporter magazine. Click here to subscribe.

Best of The Hollywood Reporter

Solve the daily Crossword