"As long as you can talk, you have a voice": An epic Bruce Dickinson interview

Bruce Dickinson has a didgeridoo. He’s owned the indigenous Australian wind instrument for years, but has yet to master it. “I’ve passed out a few times, trying to do the circular breathing,” he reveals. “I get as far as semi-circular breathing and then it’s all over.”

Dickinson hopes to pick up some tips when he visits Australia soon. His psychologist friend Kevin has also brokered a deal for them to attend a ceremony, access to which is usually denied to non-aboriginal people. “I’m looking forward to experiencing more of the culture,” he says, breezily.

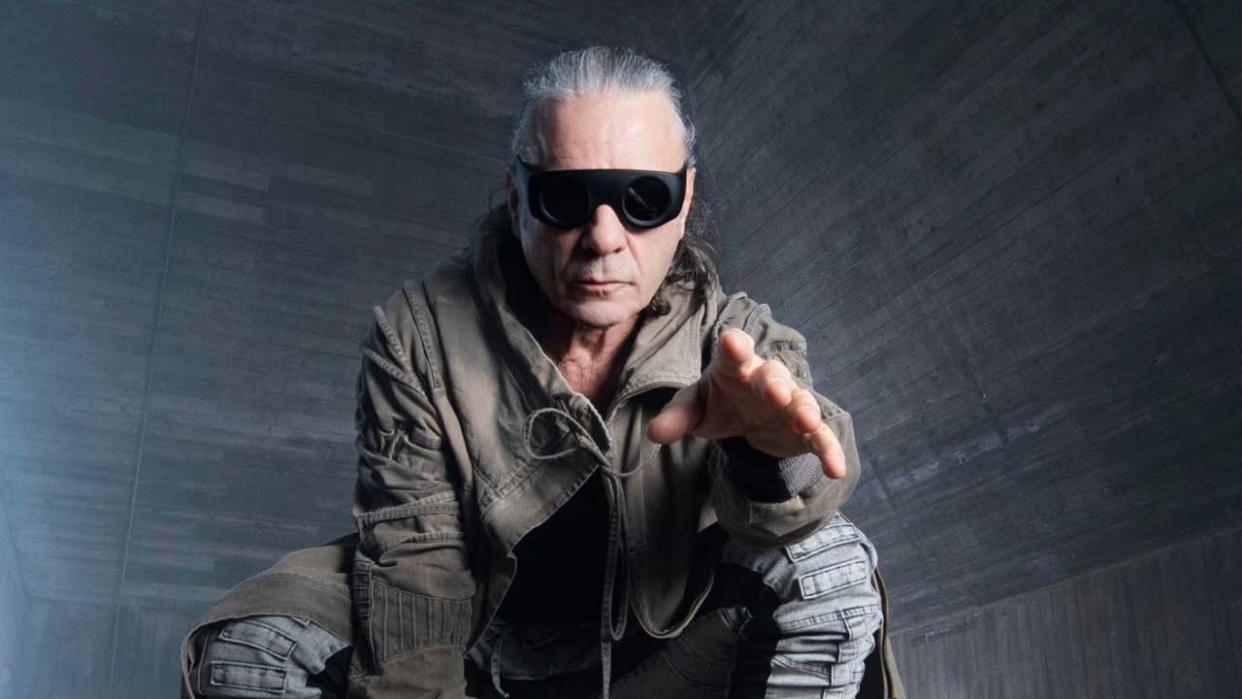

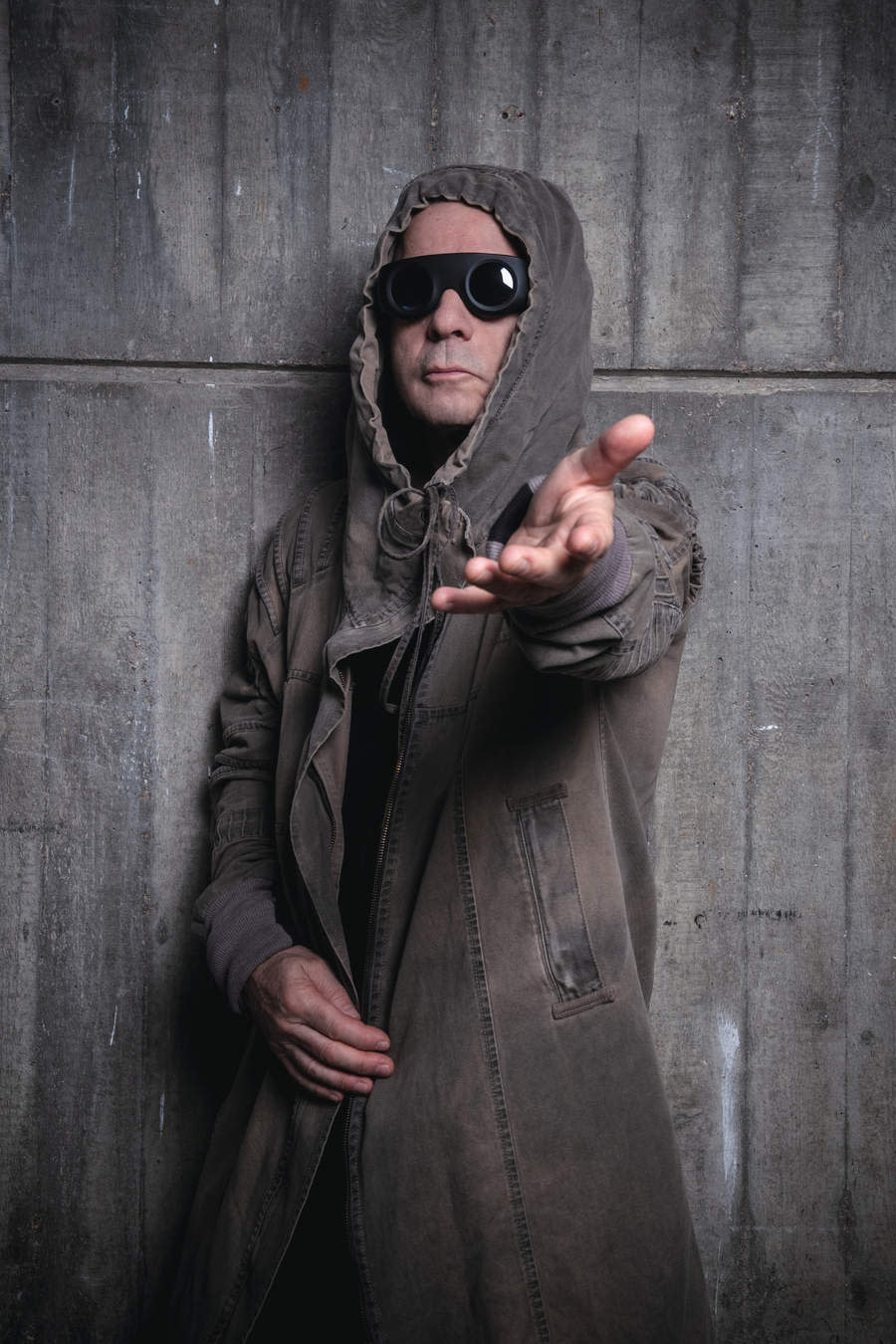

The eternally curious Dickinson is in a breezy mood. He’s releasing a new solo album, The Mandrake Project (which reunites him with long-time collaborator guitarist/producer Roy Z) on March 1, which will have an accompanying tour and a comic-book series of the same name.

You hear Dickinson arriving at Iron Maiden’s West London HQ before you see him. That familiar voice booms out from behind the Samurai Eddie cardboard cut-out guarding the doorway, and then a pint-sized colossus in black boots and with an iron-grey top-knot saunters into view.

Dickinson has fronted Iron Maiden since late 1981, barring a few years off for solo ventures and selfdiscovery. In between he’s written novels, screenplays and an autobiography; presented radio shows, fenced for his country, acquired an airline transport pilot’s licence, and helped invent a bottled ale. Just don’t mention the Vikings. More on them later…

The Mandrake Project is your first solo album since 2005. What kept you, other than being in Iron Maiden?

It’s been on the boil since 2014. Then I got diagnosed with throat cancer, then we had fucking covid, so there were two years when I couldn’t go to the USA. So by the time I reconvened with Roy Z everything had moved on.

Is this a covid project?

Not exactly. I had the idea before covid, but then it got kicked into touch because of getting ill and getting busy with Maiden. But during lockdown I was scratching my balls going: “What the fuck do I do now? Learn to cook?” Okay, but there are only so many people I can poison: myself and [new wife] Leana.

So I started writing a treatment for a sort of ‘four bikers of the apocalypse’ story, involving Eddie. During the process I was introduced to the screenwriter Kurt Sutter, who wrote [gritty biker drama] Sons Of Anarchy and [cop show] The Shield. I told him I had this other crazy idea for a screenplay, and he liked it.

That is a serious endorsement.

Yes it is. But Kurt suggested instead of a screenplay, it would make a great cartoon, a comic-book series. He recommended talking to Z2 Comics, who hooked me up with a writer called Tony Lee, who did Dracula AD and Doctor Who, and he suggested a very well-regarded cover artist, Bill Sienkiewicz [Marvel’s New Mutants]. So now we have this Watchmen-style series, which will come out in three volumes.

Is the comic the story of the album?

No [laughing]. It’s related to it, but the album has a life independent of the comic and the comic has a life independent of the album. When I got back with Roy Z, we wrote [the album’s first single] Afterglow Of Ragnarok. I thought: “I like the title, I like the chorus, it’s all good, but it’s got fuck all to do with the comic.” But then I thought, it doesn’t matter, and the album is not a concept album, because that limits you, and you end up shoehorning in things to fit the concept.

In Norse mythology, wasn’t Ragnar?k some catastrophic event that wreaked death and pestilence across the land, killing off all the gods etcetera?

Yeah. But the song’s got nothing to do with Norse mythology whatsoever. I knew that would be a problem, because as soon as you say ‘Ragnarok’ people think Vikings. I immediately thought this has unfortunate connotations, because I do not want a fucking Viking pointy helmet anywhere near the cover of this thing!

So what is The Mandrake Project story about?

The Mandrake Project aims to capture the human soul and bring people back from the dead. The two protagonists are Doctor Necropolis and Professor Lazarus. They’re like a modern-day [19th-century murderers] Burke And Hare, and both trying to raise the dead for various reasons. Necropolis is an orphan and a digital genius, tortured by the voice of his brother who died at birth. He’s also obsessed with [occultist] Aleister Crowley and sex magick, and wants to bring his brother back from the underworld.

Professor Lazarus’s father passed the secret of the Mandrake Project on to him, and now he wants to bring his father back when he dies. At the end, you realise the Mandrake Project has conquered death, which raises all sorts of philosophical questions. At the heart of the comic is the question: is the universe scientific, or poetic?

It’s a long way from Bring Your Daughter To The Slaughter.

Ha! That song was written very tongue-in-cheek. Then Steve [Harris] said: “Oh, I like that. Can I have it?” I said: “Er, okay.” I thought it was very catchy, but not sure I ever thought that was going to be a hit.

You’ve re-worked Iron Maiden’s If Eternity Should Fail as Eternity Has Failed on the new album. When you have a song idea, do you know if it’s going to be for Maiden or a solo project?

I chuck everything in Steve’s direction. That’s how it works. Then he turns around and says: “Yeah, yeah, yeah, no, no, no…” These days we tend to write more in the studio, though, so I come up with stuff specifically for Maiden. Me and Adrian [Smith] write a lot together. Steve might take a couple of ideas from Janick [Gers] and then he’ll disappear into his little hole in the ground for two to three weeks. Then he’ll suddenly emerge and go: [impersonates Harris’s voice] “I think I’ve got one.” That was how we did [2021’s] Senjutsu, which is a cracking Maiden album.

In Maiden you have to adapt to Steve Harris’s lyrics and riffs. The Mandrake Project sounds like it was written for your voice.

Yeah, they were. But I also great take pride in being able to voice Steve’s riffs. There’s not many people that can do it. I could never figure out why he wrote such bloody difficult words, though. Then we were chatting one day and it came out – the words follow the bass and drums. I tried to explain to him early on: “Look, Steve, I’m going to lose my front teeth trying to sing this.” But Steve has compromised over the years. I never thought I’d be able to sing Alexander The Great [from 1986’s Somewhere In Time] when I first heard it, but that worked out fine.

Who was the first vocalist that inspired you?

One hundred per cent Ian Gillan on Deep Purple’s In Rock. I bought a third-hand copy of it that was scratched to fuck, and I knew every note and scratch on it. After that I went straight to [Purple’s] Made In Japan, which is one of the greatest live recordings ever. Then there was the first Black Sabbath album. I didn’t get into Led Zeppelin until later when I heard Zeppelin II. Steve was a big Genesis fan. Me not so much. I was more into Van Der Graaf Generator.

You can hear parallels between your voice and Van Der Graaf’s Peter Hammill’s, but their music is scare-the-horses, hard-core prog rock. You must have been popular with your friends.

Absolutely [laughing]. “Let me just put this record on, and clear the room!” Or play it to a potential girlfriend and then wonder why she threw herself out the window. But I was playing Van Der Graaf’s H To He, Who Am The Only One and Pawn Hearts to death, along with Purple and Sabbath.

An Egyptian mummy’s mask, a vintage aviator’s flying hat, the Charge Of The Light Brigade trooper’s uniform… Where did theatrical Bruce come from?

After Deep Purple I got into Jethro Tull, and I liked Ian Anderson’s lyrics and presentation. So there’s some of that. But really it was Arthur Brown [of Fire hit single and flaming headdress fame]. Arthur is totally responsible for that operatic thing, and he was a complete showman. That’s why I had him narrating on [Dickinson’s fifth solo album] The Chemical Wedding. I was a huge fan of Arthur.

Reading your memoir, What Does This Button Do?, it seems like being at boarding school was a good apprenticeship for being in a band.

If you can put up with Oundle (public school), you can cope with life in Iron Maiden. But I’m not sure being in boarding school enables you to get on with people. People in boarding schools are not… how can I put this… normal people.

Do you consider yourself abnormal, then?

Possibly. But I was thirteen when I went to Oundle. A lot of the kids had been there since they were five or six years old, so they were completely institutionalised. Thirteen is an important age, butI didn’t have a clue what the school was all about. So of course I got the shit kicked out of me because I refused to back down, and I was a mouthy little fucker.

What happened next?

I eventually got kicked out of school [for famously urinating in the headmaster’s runner beans before a formal dinner], which was probably the best thing that ever happened to me. Then I went to what you might call a normal school in Sheffield. I thought, these people are alright, there’s no one waiting to beat you up in the corridors at night. The trouble is, it was six months before my A Levels, and I did no work at all.

What did you do instead?

I’d been studying a different syllabus at Oundle, so the teachers told me there was no point in me coming to class, just sit in the library. So I sat there and wrote lyrics for [his future band] Samson instead. I found a book on Norse mythology, funnily enough, and ripped off five lines straight for Samson’s song Hammerhead. I scraped into university with three Es, because I had an unconditional offer.

What would you have done if you hadn’t become a rock singer?

I spent four years in the army cadets. I was absolutely serious about that. But I think the army had a lucky escape. I never considered the RAF [even though Dickinson now has a pilot’s licence and has been made an Honorary Group Captain by the RAF], because I was shit at maths and thought I’d never get in. But when I got to Queen Mary’s university [in London] I was just interested in being the singer in a band.

At Queen Mary’s Dickinson studied history. A good grounding for someone who’d later sing about Macedonian kings and the Battle Of Britain. He also became the Entertainments Officer, booked Hawkwind to play a Fresher’s Ball, and borrowed the college minibus to play gigs with his early band, Shots.

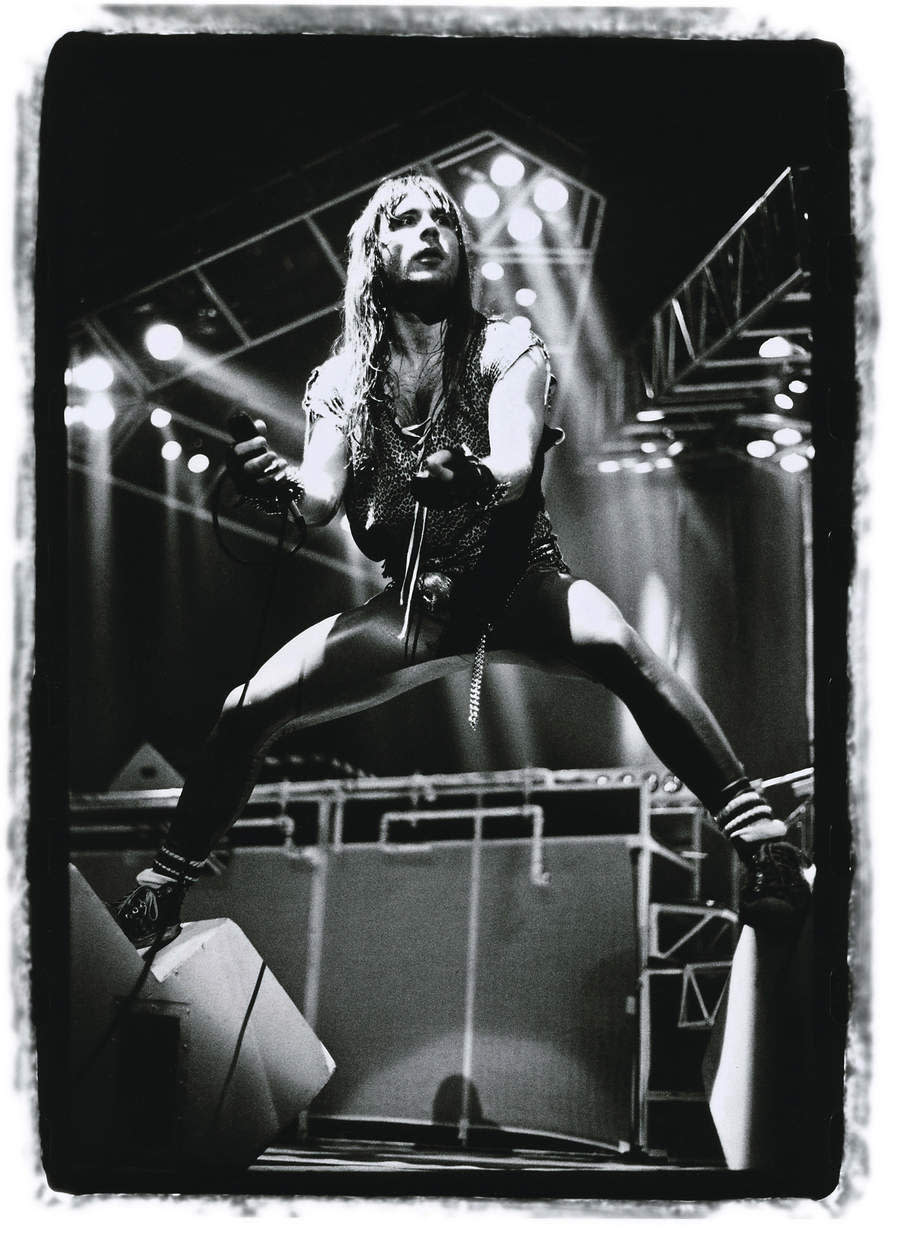

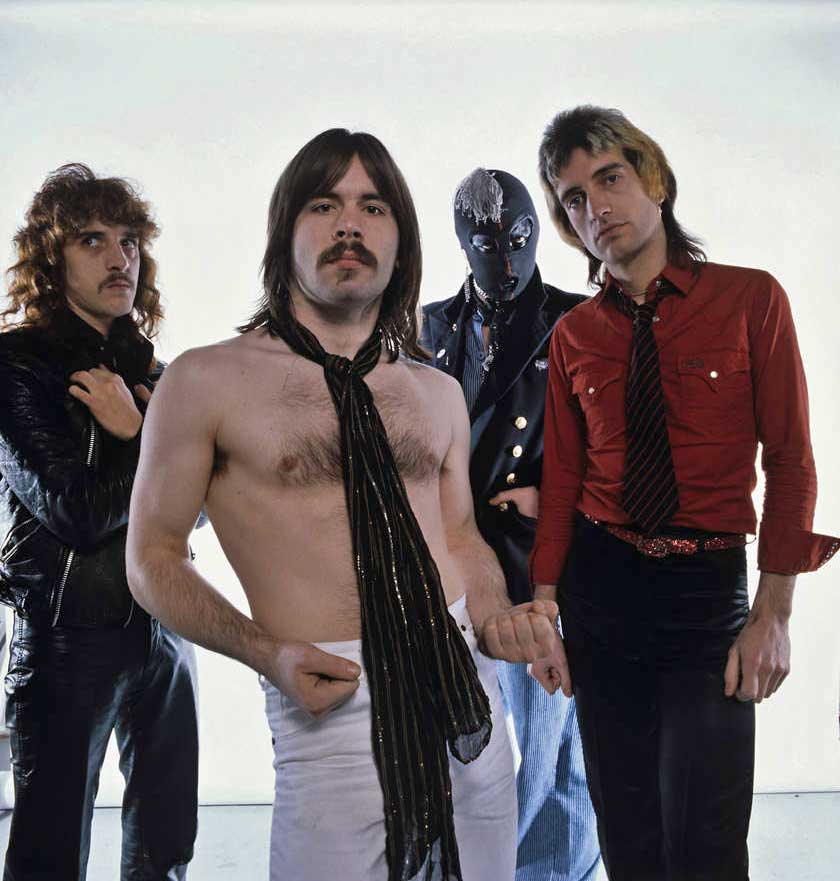

An offer to sing with middling blues-rockers Samson coincided with Dickinson’s final exams, but he joined them anyway. However, both his voice and on-stage persona were too big for Samson, and he left and joined Iron Maiden in time to appear on their third album, 1982’s The Number Of The Beast.

Did you think Samson were going to make it?

Not really. [Guitarist] Paul Samson wanted to do the bluesy thing. He was never really into heavy rock, and was a bit disparaging about it. Then we had a falling-out with management.

You never wanted to be a solo artist?

No, I always wanted to be in a band. But I remember Samson did a photo session and you’d have thought it was my solo band. I was standing about ten feet in front of the others. I saw the pictures and thought: “I can see where this is going.” But I didn’t want to be a solo artist. David Coverdale I am not. Nor probably will I ever want to be, at least not in that sense. So when the offer came to join Iron Maiden…

Did Maiden accept the fact that you were, as you put it, a “mouthy little fucker”?

They had to. I told Rod [Smallwood, manager] I am not going to be like the last bloke [previous singer Paul DiAnno]. I will push back. I also had positive ideas and opinions. I didn’t just push back for the sake of it. Someone who wasn’t a mouthy little fucker would have failed in that job.

(After recording five albums with Iron Maiden, in 1990 Dickinson released his first solo album, Tattooed Millionaire. He left the band two years later.) If you had your time again, would you still quit?

I would have done, yes. I wouldn’t have changed that, but I would have done it better [laughs]. I would have had more of a plan.

So was it a spur-of-the-moment decision to leave?

It was. I realised Iron Maiden were doing its thing and there was nothing anybody could do to change its trajectory. At the time, I was sitting there making what ended up being [second solo album, released in 1994] Balls To Picasso, and I realised that I didn’t have much clue what to do outside of Iron Maiden.

So you’d become institutionalised?

Yes. It was a shock – hang on a minute, when did this happen? And I thought what do I do about that. I made the decision that I either stay in Iron Maiden and become institutionalised for the rest of my life, or I have to leave.

You didn’t consider Tattooed Millionaire to be the beginning of a solo career?

No, it was a bunch of rock’n’roll clichés done quite well. People liked it – which I respect – but if I wanted to do something that was going to be the start of a solo career I wouldn’t have done Tattooed Millionaire. It fell into my lap. After I did Bring Your Daughter To The Slaughter [for the soundtrack to A Nightmare On Elm Street 5: The Dream Child], some A&R guy went: “I love this!” and signed me toCBS in America. I went: “Really?” We wrote that whole album in two weeks.

So there was no way that you could have run a solo career parallel to being in Maiden at that time?

I was in this state of limbo then. I thought, I have to leave, because otherwise, whatever I do, nobody’s going to take it seriously. They’ll just go: “Oh, bless his pointy little head, it’s his little side project.” I read a quote in a newspaper which finally provoked it, by [author] Henry Miller: “All growth is an unpremeditated leap in the dark with no idea of where you’re going to land.” [The quote is “All growth is a leap in the dark, a spontaneous unpremeditated act without benefit of experience”, but the point’s the same.]

Have you always been spontaneous?

All the major decisions I made in my life, I had no fucking idea where I was going to land. Like the time I was wandering around London with nowhere to live and just ten quid in my pocket. I thought I was going to have to sleep on a park bench. What shall I do with this ten quid? I know, I’ll go up to Dingwalls in Camden and buy a beer. When I got there, the sound engineer was someone I used to be in a band with. So I went up to him and asked if I could kip on his floor that night, and he said yes. That’s the way life is – you turn left, or you turn right.

Were you shocked by how some of your audience reacted to you leaving Iron Maiden?

Yes, I couldn’t understand it. Some of them told me they couldn’t even listen to Balls To Picasso at the time, because me leaving was still too raw.

You must have found that disappointing?

Absolutely. I got a bit down about the whole thing, to be honest, which is when I started to think, fuck it, I might as well get rid of me. Which is how [1996’s third solo album, and new band] Skunkworks happened. Skunkworks was a cracking album, but they weren’t really a focused rock band, and then they had this old bloke turn up to sing [laughs]. The best thing we did, though, was play in Sarajevo.

In 1994, Skunkworks were smuggled into Sarajevo to play a gig during a brutal civil war. (“I remember coming home and thinking: ‘Did that really happen?’ Because I’m now listening to these mundane conversations about things people think are important but aren’t.”)

The trip became the subject of 2016’s award-winning documentary Scream For Me Sarajevo. However, a second Skunkworks album never materialised. Dickinson quit the band, and found himself at a major crossroads in his career.

What went wrong?

I heard the demos they were coming up with, and said: “It’s not really my thing, is it.” But that band got me out of my comfort zone, and I learned a lot about singing, too. But by that point I thought: “What now?” I figured I would get a job stacking shelves or something.

Did you seriously consider becoming a train driver too?

Yes. I’d also got my airline pilot’s licence, so that was another option. But I really thought I was done with music as a career. Then the phone rang at midnight and it was Roy Z, who I’d worked with on Balls To Picasso. I told him I’d just got rid of Skunkworks, and he said he wanted to play me something. I swear it was that old cliché. He played me the intro to Accident Of Birth down the phone, and I wrote the lyrics straight after. Then I got on a plane to LA the next day.

You and Roy Z made two albums together, Accident Of Birth (1997) and The Chemical Wedding (1998), which marked the next stage in your solo career.

Accident Of Birth was a lot of fun to make and it turned everything around for me. The Chemical Wedding was the big one, artistically. That’s when I realised if I am going to do anything, I need to go deep – deep into the emotion and deep into the heart of it.

That seems to have been your philosophy when you rejoined Iron Maiden in 1999. Did you deliberate over going back? And how did the other guys respond?

I was working on what became Tyranny Of Souls [eventually released in 2005]. I took Roy and the guys in the band aside and said: “There’s something I want to run past you…” And they said: “Yeah, you’ve got to do it.” They told me it was the right thing to do.

There was a lack of compromise when you went back to Maiden. You didn’t go out and do a ‘greatest hits’ set.

Fuck! No, no, no, no, no, no, no, no, no, no, no, no no, no. Never!

It had to be about new music?

Yes. Steve was very suspicious. He said: “Why do you wanna come back?” I actually said [laughing]: “I want to come back, Steve, because, in the words of my mates, ‘the world needs Iron Maiden’, and secondly I think we can make amazing music.”

Also, they probably needed you.

Probably. But there was no point in saying that, because it would have sounded like sour grapes. What I said was: “We will sweep away the past by doing an amazing future.” Though the first words out of my gobby mouth were: “Of course we are better than Metallica!” People said: “You can’t say that.” I said: “I just did.” Then they started going: “Maybe he’s right.”

The return of the mouthy little fucker.

You’ve got to have that attitude, though. It’s like Mick Jagger didn’t get to be Mick Jagger by sitting there going [apologetically]: “Oh, we’re quite good, you know, we’re almost as good as The Beatles.” I also told them that we are not to just do ‘greatest hits’ albums, we are going to do a new album and it will be fucking great. And it was. Brave New World [in 2000] really delivered. So suddenly we’re off to the races again.

Brave New World was followed by five more Iron Maiden albums, and another Dickinson solo one, Tyranny Of Souls. Maiden and Bruce’s solo ventures now co-exist side by side. “I’ve done seven solo albums. That’s almost half of my output with Maiden,” he points out.

Dickinson’s forthcoming tour will also see him play highlights from his solo records to audiences as far afield as South America (“These people have been waiting years to see this stuff live”). Then there’s a new Iron Maiden album to be made, after his trip to Australia to, hopefully, improve his digeridoo playing.

You’ve written books, screenplays, now a comic book series… What’s left?

Really, I’ve been doing the same thing all along – telling stories. If I’m singing, I am telling a story. If I am doing a comic, it’s storytelling. I finally realised this is what I do. I love the musical part of it, but I’ve got to have a story before I’m there. When I got throat cancer, people said: “Oh my god, what’s going to happen to your voice?” I said I don’t know, but nobody actually loses their voice.

How do you mean?

As long as you can talk, you have a voice. If my voice was different, then I’ll tell stories in a different way. As a singer, your voice changes as you get older anyway. But I’ve never been absolutely tied to being a macho-man singer. Look at all the great singers that aren’t metal singers.

Who are you thinking of?

Leonard Cohen, who had a terrible voice, but he was a great singer because he was a communicator and a storyteller. Johnny Cash. Oh my god, Johnny Cash! When he did the video for [his cover of Nine Inch Nails’] Hurt, he owned the song. I remember looking at that and thinking if I was going to go out, I want to go out like that.

Is that the epitaph?

Yes, I’m a storyteller. A teller of tall tales.

The Mandrake Project is coming out on March 1 via BMG. Bruce Dickinson’s UK tour begins on May 16. Tickets are on sale now.