Lost on Boogie Mountain: How the Bee Gees’ Kid Brother, Andy Gibb, Hit the Peak of Pop Only to Die of a Coke-Broke Heart

In the late 1970s, at the same time Pablo Escobar and the Cartel de Medellín were turning Miami, Los Angeles, and New York into dumping grounds for planeloads of cocaine, Andy Gibb, kid brother to disco giants Barry, Robin, and Maurice Gibb of the Bee Gees, was the biggest teen idol in America.

It proved to be an unfortunate confluence of events. By the early ’80s, in the aftermath of a failed relationship and derailed career, Andy was hoovering a thousand dollars of blow every day. Adjusted for inflation, that’s about $3300 per day in today’s money. But, for a time at least, before his long-abused heart gave out on March 10, 1988, the British-born, Australian–raised, Miami-and-LA-residing youth phenom could afford it.

More from Spin:

Never Play Fleetwood Mac After Shock Treatment, and Other Tales of Music in the Psych Ward

Capricorn Records: The Rise and Drug-Addled Fall of the Label That Launched Southern Rock

The Gospel of Being an Ally to the Afflicted, According to Robert Randolph

In 1977–’78 Andy, not even 20 years old, had three Billboard number-one hits in a row: “I Just Want To Be Your Everything” (written by brother Barry), “(Love Is) Thicker Than Water” (written by Barry and Andy) and “Shadow Dancing” (the title track of his second album and written by the four Gibb brothers).

Over the course of three albums, Andy was the first male recording artist in American history to achieve that feat. He also amassed eight Top 20 singles between his first album, Flowing Rivers, in 1977, and his third and last, 1980’s After Dark (March of that year saw his last top ten hit, “Desire”).

Meanwhile, his brothers dropped an astonishing six consecutive number-ones between 1977 and 1979 (“How Deep Is Your Love”, “Stayin’ Alive”, “Night Fever”, “Too Much Heaven”, “Tragedy” and “Love You Inside Out”).

To this day, Andy has two songs on Billboard’s Greatest of All Time Hot 100 Songs: #33 (“I Just Want To Be Your Everything”) and #55 (“Shadow Dancing”). The Bee Gees have three: #27 (“How Deep Is Your Love”), #47 (“Night Fever”), and #66 (“Stayin’ Alive”).

To put that in perspective, not even Paul McCartney, Michael Jackson or Elton John has two songs on the list as a solo artist (they do in duets).

In September 1978 New York magazine called Andy “the world’s hottest recording star”. Bob Hope said he was America’s “hottest-selling import to hit our shores since the Toyota”.

Andy sold an estimated 20 million records in just three years. From magazine covers to telethons to celebrity galas to duets with Olivia Newton-John, you couldn’t escape him.

For good reason: Andy was handsome, polite, personable, a gifted songwriter and musician with a wonderful voice.

On his records he had behind him some of the best studio musicians in Miami, a visionary and irrepressible manager, fellow Australian Robert Stigwood (who’d masterminded the seismic cultural event that was Saturday Night Fever), and two crack producers in Albhy Galuten and Karl Richardson (who’d worked on Fever).

But most critically of all, he possessed a direct line to the greatest songwriting engine room outside the Beatles in pop-music history: his older brothers, the Bee Gees.

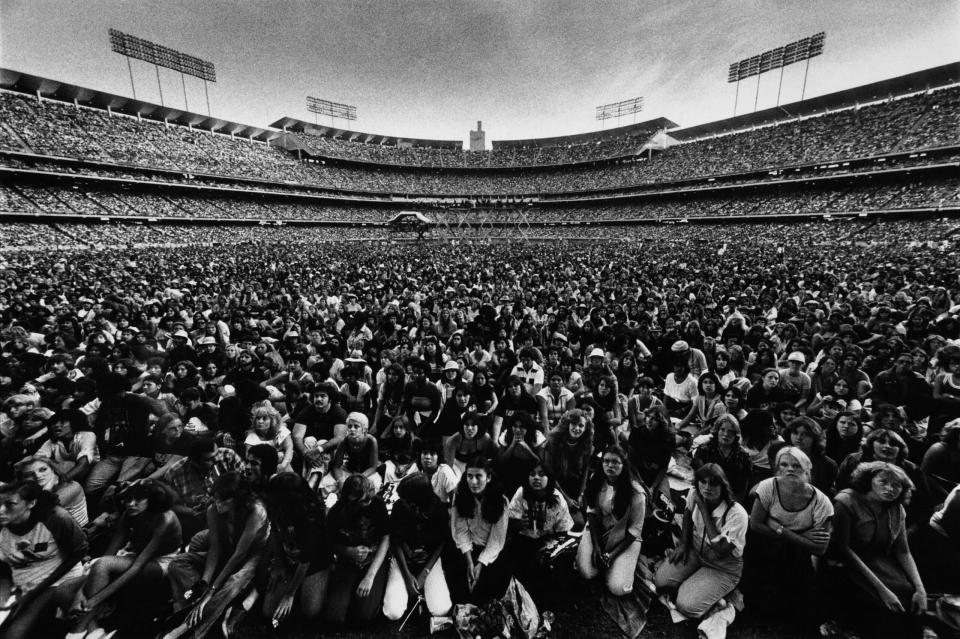

Andy came close to joining the Bee Gees as a permanent fourth member (it was even officially announced before he died) and you can see how the four Gibbs would have been as a group by watching them together performing “You Should Be Dancing” in Oakland in 1979. Andy is like a clean-shaven, younger (twins Maurice and Robin were about nine years older than him, with Barry a dozen years his senior), even more striking (if it were humanly possible) version of the leonine, blond-flecked Barry, with a similar falsetto and vibrato and perfect pitch.

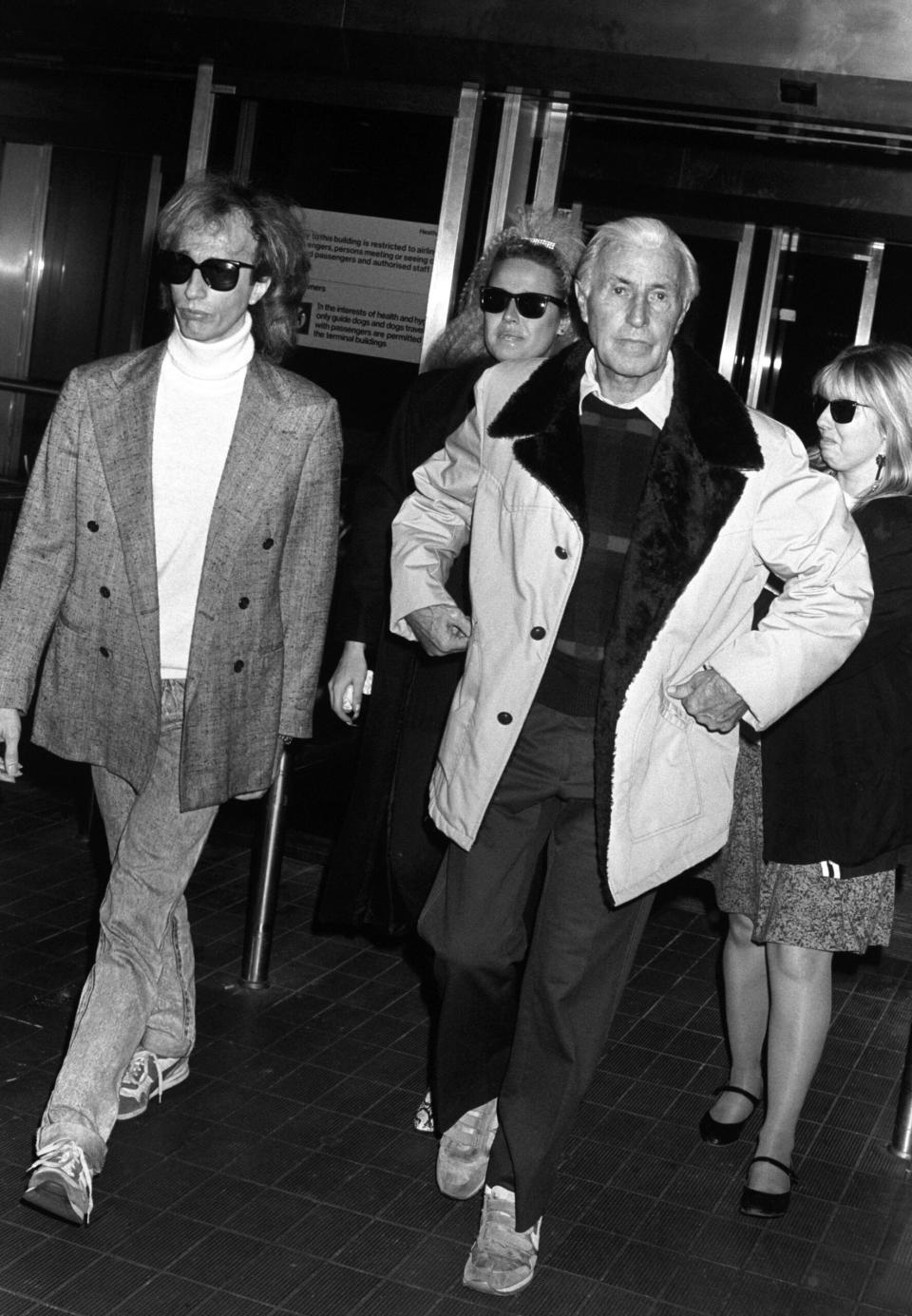

But when the Bee Gees and disco became so unfashionable as to be considered utterly toxic, Andy’s life played out like a real-life Boogie Nights. Shuttling between Florida and California, struggling with a growing cocaine habit, he was out of a record contract by 1980 and fell out with and got into debt to Stigwood.

The music industry was about to change irrevocably with the arrival of MTV and Andy had become a glitter-ball relic no one wanted to touch. Various lifelines were offered to him (a hosting role on Solid Gold, starring parts on Broadway in The Pirates of Penzance and Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat) but he failed to seize these opportunities.

Nevertheless, in 1981, in somewhat of a professional nadir at the age of 23, Andy became arguably better known as the boyfriend of 31-year-old Dallas star, September 1973 Playboy Playmate and recent divorcee Victoria Principal.

Their attraction to each other was sparked that year on the set of The John Davidson Show, the high-glam couple later recording a song together, a cover of the Everly Brothers’ “All I Have To Do Is Dream” (which went to #51).

After eyebrows were raised about the age gap (unremarkable though it was, especially if the genders were reversed), Principal said on The Phil Donahue Show: “Young men seem to mature faster than when I was growing up.”

But Principal dumped Andy within 13 months, later speaking of the rampant drug habit he carried into their relationship. She remarried in 1985.

Andy booked into rehab; he struggled with depression and anxiety, and was beset by panic attacks; he lost his millions and filed for bankruptcy; and as the ’80s wore on, he was living in a flat paid for by his brothers and getting by on a $200-a-week allowance.

In 1986 Andy earned just $8000. By 1987, he was trying to get his life back on track and had recorded four songs in the studio for a comeback album that was never released (one of them being the notable “Man on Fire”, released as the opening track on the posthumous 1991 greatest-hits collection, Andy Gibb).

On March 10, 1988, five days after his 30th birthday, Andy died at John Radcliffe Hospital in Oxford, England, with myocarditis (inflammation of the heart) the official cause of death, most likely from years of rampant coke abuse.

But as much as his musical achievements were impressive in such a short space of time, it’s the personal tale behind the record sales and the number-one hits that is the heart of the real Andy Gibb story. It’s much darker than all those flashbulb-popping, gloriously dentured promotional pictures from his musical career might suggest.

His agent from 1983 to ’85, Jeff Witjas, once said of Andy, “When he looked in the mirror, you always had the feeling he didn’t see anything.”

How was that possible? How could a man who had had everything – fame, looks, connections, money, adoration; he was one of the Gibb brothers, for god’s sake – bottom out so completely in the space of ten years?

Perhaps the greatest tragedy of Andy’s wasted life was that he’d had a wife, Kim Reeder, whom he’d married in Australia in 1976, and in 1978 their relationship produced a young daughter, Peta – something to center him among all the craziness. (His celebrity ex, Victoria Principal, had spoken to the press about bringing an adopted child into their relationship, saying that at 33 years of age she was too old to bear one herself.)

However, that year Kim divorced Andy because of his drug use and chose to return from the US to Australia, where Peta was born. As he chased stardom in America, Andy barely came to know his own child.

When in the mid 1980s he belatedly decided he wanted to be a better father, Andy’s clarity on what was really important in life all came far too late.

In Miami, just months before his death, Andy, a licensed pilot, told freelance journalist Malcolm Balfour: “The only time I get high these days is when I’m flying an airplane. I can promise you one thing – no matter what happened to me in recent years, I’ve had 18 wonderfully clean months in Florida. The future has never been brighter […] I’m totally off drugs.”

I met Barry Gibb’s eldest son, Stephen Gibb, in Miami in 2019 to talk about the possibility of writing an Andy Gibb biography with the family’s blessing, and he was nothing but supportive, telling me Andy was his favorite uncle, and that the Gibb family cherished and was very protective of Andy’s memory.

Stephen, a musician, had had his own battles with alcohol and cocaine addiction. In 2020, he had his own podcast on addiction, Addiction Talks.

Robin’s son, Spencer, and Peta had sent me kind emails. Barry had been absolutely devastated by Andy’s death. He’d remarked in an interview, “Andy and I were twins just as much as Robin and Maurice were, in every sense of the word. We looked alike, we had similar moles, similar birthmarks, everything.”

I felt at the time, as I still do, that Andy’s story was an American showbiz tragedy with all the elements of a gripping, dramatic TV series.

His dependence on drugs and private despair also had unexpected parallels to the life of another fallen Australian music star, Bon Scott of hard-rock band AC/DC, whose biography I’d written two years earlier. I felt real empathy for Andy as I had Bon.

But as Stephen told me, the family (and Barry, as executive producer) was preoccupied with an upcoming Paramount-bankrolled Bee Gees biopic that had been greenlighted largely due to the success of the 2018 Freddie Mercury/Queen biopic, Bohemian Rhapsody.

The Bee Gees film was at the time attached to British director Kenneth Branagh but has since been handed over to Irish director John Carney (no release date is publicly known). I was told Barry was also (slowly) writing his own memoir. That was the last time Stephen and I spoke about it. It just fell to the wayside, like a lot of these ideas and projects do.

Perhaps one day Hollywood will realise there’s an even more incredible story than the Bee Gees in the dark, unsettling, very human but fascinating tale of their little brother, Andy Gibb.

How the upcoming biopic features Andy and his relationship with his three brothers will be interesting to see, though I do remember Stephen saying Barry and the producers had been very mindful to make Andy an integral part of the screenplay.

Either way, 35 years on, Andy Gibb and his music shouldn’t be forgotten.

To see our running list of the top 100 greatest rock stars of all time, click here.

The post The Gospel of Being an Ally to the Afflicted, According to Robert Randolph appeared first on SPIN.