A Lotta Love to Give: The Brilliant Voice and Too-Short Life of Nicolette Larson

When Nicolette Larson was growing up in Kansas City, Missouri, she’d ask her friends to drive over bumpy roads so she could show off her Neil Young impression. As the truck moved up and down, she’d break out into a shaky vibrato.

Just a few years later, the singer found herself in a pickup again, this time with the very man she once emulated. Young — who first worked with Larson on his 1977 LP American Stars ‘n Bars, and briefly dated her afterward — was driving her around his Northern California ranch when she spotted a cassette tape on the floor containing songs that would wind up on his 1978 album Comes a Time.

More from Rolling Stone

“I picked it up, blew the dust off it, I stuck it in the cassette player, and ‘Lotta Love’ came on,” she told Jimmy McDonough in the Young biography Shakey. “I said, ‘Neil, that’s a really good song.’ He said, ‘You want it? It’s yours.’”

Larson recorded “Lotta Love” for her 1978 debut, Nicolette, which coincidentally landed on shelves the same day as Comes a Time. Produced by Ted Templeman, who also helmed records by Van Halen and the Doobie Brothers that same year, the song immediately transformed her from an obscure backup singer to a hit solo artist, peaking at Number Eight on the Billboard Hot 100. Rolling Stone called her the Female Singer of the Year, writing, “No one else could sound like she’s having so much fun for a whole album.”

But Larson’s time in the spotlight was extremely brief. Though she continued to make albums with Templeman into the next decade, she failed to become a star like her friend and roommate Linda Ronstadt. She ventured into country in the mid-Eighties, released a children’s lullaby album in 1994, and unexpectedly died of a cerebral edema in 1997. At the time, she was married to drummer Russ Kunkel and raising a seven-year-old daughter. She was just 45 years old.

Larson has remained relatively unknown to all but die-hard aficionados in the years since, but that may change when Young releases the long-awaited third volume of his Archives series, which will include a previously unheard tape of the two rehearsing with an orchestra in 1977. It will pull the curtain back on Young’s creative process and reveal the integral role Larson played in the creation of some of his most enduring music.

“She was absolutely fearless,” Young tells Rolling Stone of Larson. “She told me, ‘I’m the best one. I can follow you anywhere you want to go. No one can follow you better than I can.’ And she could.”

“With the possible exception of [Crazy Horse guitarist] Danny Whitten, Nicolette sang better with Neil than anyone,” says Young archivist and photographer Joel Bernstein. “Nicolette and Danny absolutely were the two best singers with Neil who really understood his singing, his soulfulness, and what to get across. When you hear Comes a Time now, many years later, it pulls at your heartstrings as much as it did the first time you heard it.”

The tape might also shed light on Larson’s life and career, and show that she was much more than a one-hit wonder with a unique dating history (she also was linked to Cameron Crowe, “Weird Al” Yankovic, and others). “It’s got to be so different for a female in this business, especially back then, and that’s all I’ll say on that,” Steve Wariner, who duetted with Larson on the country hit “That’s How You Know When Love’s Right,” tells Rolling Stone. “She’s one of the best-kept secrets in music. The world should know her.”

Before she sang at the kitchen table she shared with Ronstadt, Larson first learned music in her family home, practicing piano and guitar as a child. She was born on July 17, 1952, in Helena, Montana, one of six children: Bobby, Danny, Nicolette — or Nicci, as they called her — Mike, Judy, and Heather.

Larson’s father, Bob, worked in the U.S. Treasury Department, so the family moved frequently. Larson had lived in St. Louis; Boston; Alexandria, Virginia; Birmingham, Alabama; and Portland, Oregon, before the family settled in Kansas City.

“It’s hectic when you have that many kids,” Mike, who is five years younger than Larson, says. “It was one bathroom, one phone, one TV, everybody was jammed into a couple of rooms. It wasn’t a big house. And dinner time was always together.”

Larson attended Bishop Hogan High School, and in interviews she’d look back on her youth and describe herself as unpopular, yet not an outcast. She was a member of the chorus, but not a cheerleader — and she certainly didn’t attend her prom. Her senior photo, incorrectly labeled “Nicki Larson,” shows her looking apprehensive, with a string of pearls around her neck.

Courtesy of Elsie May

“I wasn’t that groovy in high school, I wasn’t that popular,” she told Crawdaddy, then rebranded as Feature, in one of the magazine’s final issues, in May 1979. “I mean, I wasn’t the dog, I wasn’t the one in class that nobody would sit next to, but I wasn’t comfortable, either. Everybody’s idea of a good time was getting a case of beer and sitting around fumbling with one another in somebody’s basement. I thought sex and romance were going to be great, magnificent. The first time it wasn’t that great, but at least it wasn’t in somebody’s basement.”

Her chorus instructor Sister Mary Madeleva told The Kansas City Star in 1997 that Larson was “one of those quiet little creatures in the front row,” while Louis Read, who taught world history and humanities, described her as a neat student who stayed out of trouble. “Her senior year she had become kind of, well, she was into long hair and peace, very into music,” he recalled. “She was very aware of a lot of the stuff that was going on, more so than some of the kids.”

That long hair would become Larson’s signature look, often reaching below her waist and swaying chaotically back and forth as she delivered harmonies. Following her graduation in 1970, she waitressed and briefly attended the University of Missouri Kansas City before deciding to pursue music full time. “I wanted to be a musician, something different than a secretary or waitress,” she told Crowe in Rolling Stone. “Kansas City wasn’t the place.” Like so many singers of the era, she headed to the West Coast.

It’s unsurprising that Larson’s father disagreed with her career choice. “I thought it was a waste of time,” he told The Kansas City Star in 1982. “How many girls go out there to be singers, and how many of them make it?” But Larson would be one of the few who did. She got a job at a record store in Berkeley, began hanging around clubs, and landed a gig as a production secretary at the Golden State Country Bluegrass Festival.

It was through the festival that Larson began performing. She opened for Eric Andersen, and sang with Commander Cody and Hoyt Axton. (Axton even brought Larson on the road in 1975, when his Banana Band opened for Joan Baez on her Diamonds & Rust tour.)

But it was a chance meeting with songwriter and Buddhist teacher David Nichtern a year earlier that helped Larson’s career take off. Nichtern, who wrote Maria Muldaur’s “Midnight at the Oasis,” was performing with his band at the Sweetwater Saloon in Mill Valley, California, one evening, when Larson and a friend approached them at soundcheck. He soon hired Larson to sing in his band. “I think it’s fair to say I discovered her,” Nichtern says. “It was called Nichtern and the Nocturns and Nicolette, but she didn’t get billing.”

All these years later, Nichtern can still recall Larson’s unique ability to harmonize. “She had this really graceful gift of being able to wrap herself around the lead vocal and make it feel like you had rehearsed for a million years already,” he said. “It was like if you get a good suit, and it fits. It had that custom-tailored kind of feeling.”

That same evening at the Saloon, Larson also met Nichtern’s pedal-steel guitarist Hank DeVito, who would become her first husband. “They had a lot of spark between them,” Nichtern says. “I had this total flash of intuition that she and Hank were going to get married. I literally said, ‘Do you, Hank DeVito, take — what’s your name? Nicolette Larson? — to be your lawfully wedded wife?’”

DeVito also remembers he was instantly taken with Larson: “She was charming as hell when I first met her.”

Larson and DeVito married that year on the coast, north of Santa Barbara. In attendance was musician and best man Rodney Crowell, and his then-wife Muffin and their six-month-old daughter, Hannah. After the couple said their vows, they ate Mexican food and drank margaritas. “They found an old Indian medicine man,” Crowell remembers. “Just a California outdoors wedding.”

In early 1975, DeVito and Crowell joined Emmylou Harris’ Hot Band, leading Larson to duet with Harris on “Hello Stranger,” off 1977’s Luxury Liner. She had already racked up several recording credits that year — from Crowell’s solo debut Ain’t Living Long Like This to actress Mary Kay Place’s Aimin’ to Please — but “Hello Stranger” showcases Larson’s abilities beyond harmonizing. She delivers powerhouse vocals, trading off lines with Harris while completely in sync.

Harris introduced Larson to Ronstadt, and the two became fast friends. “Our lives were very similar,” Ronstadt says. “We were very close. We knew what was going on in each other’s lives and what you were wearing and who your boyfriend was and what books you were reading. We shared everything.”

Ed Perlstein/Redferns/Getty Images

Larson and Ronstadt would often go shopping for clothes to wear on tour, especially in the summer, when it was sweltering during the day and chilly at night. It was with Larson that Ronstadt bought her iconic Cub Scouts uniform at an Army surplus store in New York, while Larson bought Hawaiian button down T-shirts.

“It was perfect outdoor wear,” Ronstadt says. “She was gorgeous, and she had that hair. The less makeup she wore, the better she looked.”

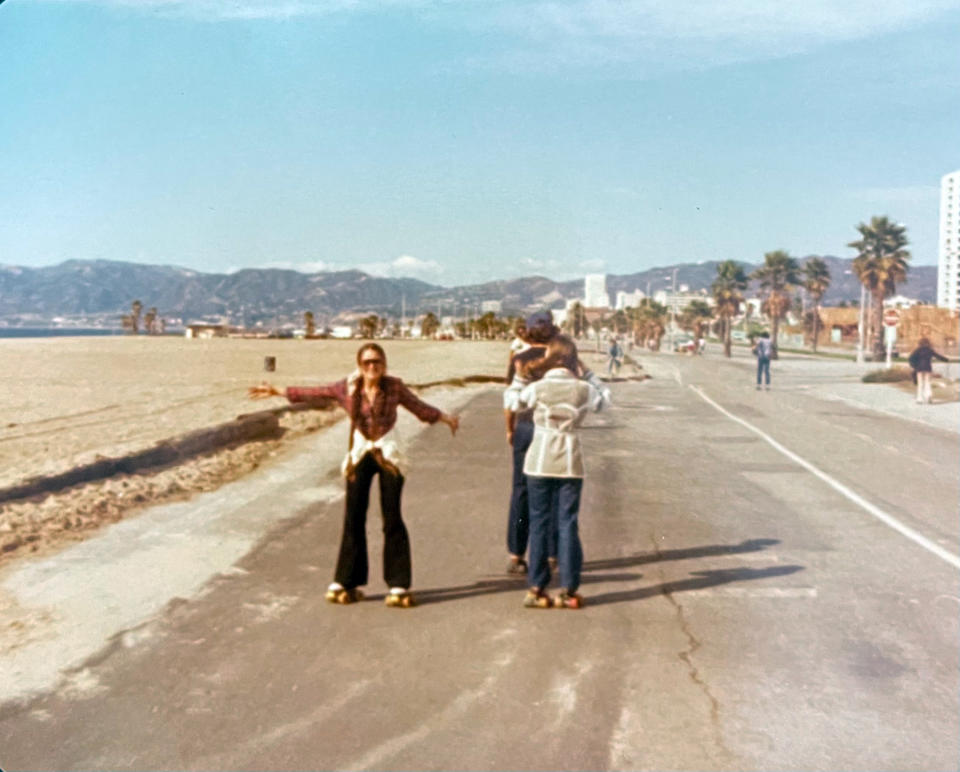

Larson also got Ronstadt into roller skating; the pair Ronstadt wears on the cover of 1978’s Living in the USA was a gift from her friend. “We only knew how to go forward, we didn’t know how to stop,” Ronstadt says with a laugh. “I don’t know why we weren’t nervous. We weren’t good skaters.”

One evening, around 11 p.m., Ronstadt received a phone call at her home in Malibu. It was Neil Young, asking if she’d lend some harmonies to his upcoming record, American Stars ‘n Bars. “He said, ‘You know anybody else?’” Ronstadt recalls. “I said, ‘Well, Nicolette Larson’s here. We’ll try.’”

Young remembers coming over that evening with his producer, David Briggs: “We’re sitting around a table and we put down a cassette recorder and as I played all these songs for the first time, they started singing them.”

In Shakey, Larson remembers how Young greeted her that rainy night. “He said, ‘I guess I’m supposed to meet you, ‘cause I called three people lookin’ for a singer and everyone told me your name.’ Neil’s kinda cosmic about things like that.”

Young named Larson and Ronstadt the Saddlebags, and the singers headed up to Broken Arrow Ranch to record, providing swirling, cozy backing vocals to “The Old Country Waltz,” “Hold Back the Tears,” and other songs. American Stars ‘n Bars came out that May.

In the fall of 1977, Young asked Larson to come to Nashville to record his next album, Comes a Time. He had already completed a solo acoustic record in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, but Warner Bros. suggested he overdub all the tracks with a band — something Young rarely did. “Piecing together things can be a very artistic thing to do, but it’s not what I like to do,” he says. “I like to perform a song, feel the energy, and then leave.”

But Young agreed, and recruited drummer Karl Himmel, steel guitarist Ben Keith, bassist Tim Drummond, fiddle player Rufus Thibodeaux, Spooner Oldham on keys, and Larson. Keith and Himmel both hired acoustic guitar players by accident, and Young used them anyway — resulting in eight acoustic guitarists on the record.

Comes a Time contains some of Young’s most beautiful material — the songs are earthy and intimate, with Larson’s tender vocals blanketed over top. Her voice intertwines perfectly with Young’s on tear-jerkers like “Already One” and the Ian & Sylvia cover “Four Strong Winds.”

“If I was singing, she was right there with me, like a semi-fraction of a second behind, going everywhere I went,” Young says. “It was uncanny.”

When Larson returned to Los Angeles, where she was living with DeVito, just east of Marina Del Rey, she confessed to her husband she’d been having an affair. “She fell in love with Neil Young,” DeVito says. “From there, it just fell apart. I assumed she was leaving me anyway, because she ended up going north to Neil’s ranch. She was very ambitious, so the Neil Young connection was a lot better than a sideman for Emmylou.”

DeVito recounted the breakup in “Queen of Hearts,” which was a hit for Juice Newton in 1981. The lines “The Joker ain’t the only fool/Who’ll do anythin’ for you” make it obvious who it’s about. “It’s Hank writing about her,” Joel Bernstein says. “The Joker is Neil.”

Larson and DeVito divorced in 1978. Crowell recalls how devastated DeVito was: “It was a tragedy for Hank. We were young and out on the road, and we were silly boys, but never Hank. Hank was steadfast, committed, and the rest of us were just dogs. It seemed unfair that Hank, the most all-true husband, was the one who would get dumped by a chance encounter with a rock & roll star. So I always thought, ‘Why Hank? He doesn’t deserve this.’ But I completely understood when Nicolette fell under Neil Young’s spell. I would’ve.”

“I’m seconding that emotion,” Nichtern says. “[Hank] was just looking for true love. In the end, he thought he found it.”

In November, Young returned to Nashville to rehearse with the musicians from Comes a Time and his Give to the Wind Orchestra — which the public will finally get to hear this year. The following day, they flew to Miami for a benefit show he spontaneously decided to perform on his birthday. The concert was held at Bicentennial Park, and admission was free, with donations going toward the South Florida Chapter of the National Hemophilia Foundation, the Pediatric Care Center, and other causes.

Carlos Rene Perez/AP

For Young die-hards, the Miami concert is notable for his tribute to Lynyrd Skynyrd; he covered “Sweet Home Alabama” and dedicated it to “some friends in the sky,” referring to their fatal plane crash the month before. But for Bernstein, the highlight of the day was sitting on the bus prior to the show with just Young and Larson, listening to them duet on Comes a Time songs — a private concert, for one.

It’s unclear exactly when Young and Larson split, but it was sometime before the holidays that year. Larson likened the romance to a Hollywood fling. “Neil and I had a brief relationship, probably no more than in a movie where a leading man and leading lady get a crush on each other,” she told McDonough in Shakey. “He wasn’t involved, and I was in a relationship that was falling apart. It was pretty much over — whatever it was — by Christmas.”

Young admitted to McDonough that he essentially ghosted Larson — “I just kinda disappeared from that relationship” — while Himmel confirms Young “disappeared and left town.” But all of these years later, Young says their musical bond is what matters most. “It didn’t matter what was going on,” he says. “The music was first with us, and we really loved playing and singing together.”

Young’s half-sister, Astrid, who sang with Larson and remained friends with her for the rest of her life, agrees: “Where she was at in her career and what she was doing was not really what he was looking for. I think he wanted something that was a little bit more home. [They] were on different roads. Even though they parted ways on a personal level, I think they still had a lot of love and respect for each other. Neil valued her so much on the work that she did with his music that was so incredibly pivotal to the sound at the time.”

Larson moved in with Ronstadt after the breakup, telling Crawdaddy, “One thing that I learned from the whole Neil episode: Good friends are essential. Linda pulled me through so much of that.” Ronstadt tells Rolling Stone she thought the split was for the best: “We go through those things, and they’re a drag. It was hard for her because they sang really well together, but I don’t think it was meant to be. Neil is really sweet, but he’s moody, and I think that was puzzling to Nicolette. He’s a real complicated guy, and he’s got a wonderful heart.”

Naturally, when her cover of “Lotta Love” hit the charts, Larson was frequently asked about the relationship in interviews. “People are always asking me to talk about Neil,” she said. “It drives me nuts. It’s nothing bitter, it’s just very taxing.” But with the single came her 1978 debut album, Nicolette, signaling her pivot away from backup singing. From now on, Larson would be doing things on her own terms.

Like she did with Young, Ronstadt introduced Larson to Warner Bros. vice president Ted Templeman. “She called me up and said, ‘Teddy, I’ve got just the ticket for you!'” Templeman recalls. “‘I’m having lunch with her right now. Her name’s Nicolette Larson. You’ve got to hear this girl.'”

Templeman initially didn’t think Larson’s voice was distinct enough. “I always feel that you need to be identifiable,” he says. “You can’t just be a voice out there. Nicolette didn’t sit apart like that. She just sounded like another background singer to me.” In an interview with Crowe, Larson echoed the same opinion of herself: “I worried that I wasn’t unique enough. ‘I sound like Emmylou’ or ‘I sound like Bonnie Raitt.’ I just figured my own style would evolve naturally.”

But Templeman took a chance on Larson and signed her. He even saw Larson’s role as an interpreter — rather than a songwriter — in a positive light. “Frank Sinatra never wrote a song,” he says. The two began selecting songs for her to cover on the album, and ended up with everything from R&B classics like Sam Cooke’s “You Send Me” to the wistful folk of Burt Bacharach and Bob Hilliard’s “Mexican Divorce.”

Holed up at Amigo Studios in Los Angeles, Templeman and Larson recruited Little Feat keyboardist Bill Payne and guitarist Paul Barrere, the Doobie Brothers’ Michael McDonald and percussionist Bobby LaKind, Ronstadt and Valerie Carter on backing vocals, and other musicians to record. In between takes, Larson would ride around on her roller skates.

Courtesy of Mike Larson

Eddie Van Halen contributed a solo to Lauren “Chunky” Wood’s “Can’t Get Away From You,” but his bandmates didn’t want him credited. “Ed did it as a favor to me,” Templeman says. “They had a little agreement where nobody in the band would ever play [on] anybody else’s record.” However, the band did record a parody of “Lotta Love,” changing the words to “Lotta Drugs.”

There are several differing accounts of how Larson discovered “Lotta Love.” In Shakey, Larson picks up the cassette tape off the floor of Young’s truck. Karl Himmel tells Rolling Stone it was he who was driving the truck, while Ronstadt claims she was the one who introduced the song to Larson and Templeman. Bernstein also remembers teaching Larson the song on guitar. However it came about, the single almost didn’t happen.

Templeman was having difficulty coming up with an arrangement for the cover, and they were nearing the end of their sessions. “I didn’t know what the hell I was going to do,” he tells Rolling Stone. “Because, to me, it was just another folk song.”

But one day while driving, he had an epiphany when Ace’s “How Long” came on the radio. “I got in the studio and I said, ‘Don’t talk, everybody!’ and I played the chords,” he says. He fleshed out the arrangement with Payne, adding a sax line and a disco bass run that was popular at the time. “I stole that whole chord change, to put an intro,” he says.

Nicolette was released on Sept. 29, 1978, landing on the Billboard 200 a month later. The single “Rhumba Girl” followed “Lotta Love,” and the album peaked at Number 15 in March of the following year.

Despite Larson’s success, some male critics didn’t embrace the album. “I’ve liked this woman on record with Neil Young and on stage with Commander Cody, but her solo debut is the worst kind of backup-chick garbage,” Robert Christgau wrote in Record Guide: Rock Albums of the Seventies.

Rolling Stone was kinder: “Her voice doesn’t have the plaintiveness or sheer beauty of Ronstadt’s or Harris’ or Dolly Parton’s,” wrote John Rockwell. “None of [this] is a serious problem, to be sure. There’s a lot on Nicolette that’s already very good, and Larson is still a young, growing singer.”

On Dec. 20 1978, Larson performed at the Roxy in Los Angeles, one of her first few shows with her band. Actress Mary Kay Place introduced her onstage as “the only person on the charts today who can sit on her personal hair.” According to the Crawdaddy profile, Larson wore a burgundy silk blouse and jeans, delivering tracks from her debut. The performance was recorded, and Warner Bros. released the live album as a promo.

Following a tour to support the debut, Larson and Templeman went to work on a follow-up, 1979’s In the Nick of Time. Although the album featured “Let Me Go Love,” a yacht-rock duet with Michael McDonald that sailed to Number Nine on the Adult Contemporary chart, the album was unable to maintain the momentum of the debut. It spent 21 weeks on the Billboard 200, peaking at Number 47.

Andrea Bernstein

“It was a tough reminder for me, and for her, that it’s really hard to find and deliver a hit single,” Templeman said. “In this case, lightning didn’t strike twice.”

Her next record, 1981’s Radioland, performed even worse, failing to crack the top 50 on the Billboard 200. It was her final album with Templeman. “Ten years from now, I would hope that I wouldn’t be too much of a memory,” she told DJ and promoter Billy Brill ahead of the release, already feeling like a one-hit wonder. “I would hope that I was remembered as someone who made good music.”

Larson’s final release on Warner was 1982’s All Dressed Up and No Place to Go. The record showed Larson fully immersed in the Eighties, from the cheesy arrangements to the bubblegum-pink towel she wears in the shower on the album cover.

The record was produced by Andrew Gold — whom Larson was briefly engaged to — and they co-wrote the saxophone-laden “I Want You So Bad.” “I was real skeptical of that,” she told Fort Lauderdale News on working with her significant other. “I queried Andrew on this. I didn’t want to sacrifice a romance for a record. Being together all the time is rough. You need a very strong relationship. Ours wasn’t.”

Although her cover of “I Only Want to Be With You” landed on Billboard’s Hot 100, All Dressed Up and No Place to Go was another flop. Warner dropped her following its release.

“I know how fragile success can be, how intangible and fickle it all is,” Larson told The Kansas City Star that year. “Having a hit at the beginning like that is a little odd. But then that’s better than spending four years trying to bust through and going through all that frustration. At least I know I can do it.”

Larson ventured into musicals over the next couple of years, including a role in Pump Boys and Dinettes and — oddly enough — Jesus Christ Superstar, with David Cassidy. She was looking for a career renewal, a way to retrace her steps back to “Lotta Love,” embarking on any path that would lead her there.

“She went whichever direction,” her brother Mike says. “Something would come up, and she goes, ‘Oh, I’m going to do that.’ I said, ‘What about this?’ [And she’d say], ‘I want to do this now.’” In 1984, that path suddenly became clear to Larson. She fired her manager, booking agent, and accountant, and headed south.

Donn Landee*

It’s almost impossible to talk about country music in the Eighties without mentioning the name Jimmy Bowen. The producer was a former teenage rockabilly singer who became Frank Sinatra’s producer in the Sixties. He won Record of the Year for 1966’s “Strangers in the Night,” becoming a Grammy winner at just 30 years old.

In 1977, Bowen packed his bags for Tennessee, and six years later, he became the president of MCA Nashville. “Nashville at that particular point in time was in transition,” says Russ Kunkel. “Jimmy had come to town and shaken things up.”

Bowen revolutionized the genre, shifting from analog recording to digital. “That was blowing my mind,” says Steve Wariner, who signed with Bowen’s label in 1984. “Technically speaking, the world of country was changing.”

Also changing were the amount of signees outside of Nashville. Pop artists were crossing over to the genre, from Kenny Rogers to the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band to Orleans. “A lot of artists were going, ‘Hey, we’re not so big in pop anymore. We’ll go to Nashville and be a big fish in a small pond,’” says Tony Brown, whom Bowen hired as executive vice president and head of A&R. “All of the sudden, it wasn’t so embarrassing to be in country music.”

It was Brown’s love of the Eagles and country rock that led him to signing Larson. “That’s my favorite kind of music, so it’s only natural that I jump at the chance to sign Nicolette to the label at the time,” he recalls. “I thought it would be a rebirth of her career, and a big feather in my hat.”

Brown and Emory Gordy Jr. produced Larson’s 1985 country debut, …Say When. Despite the Academy of Country Music naming her Best New Vocalist that same year, the album was another misfire.

“I think it’s very fair of country programmers to be protective of their audience, but I think I’ve made a sincere album that should be evaluated seriously,” she told Billboard. “In one sense, it would be easier if I were starting out completely new, instead of as the girl who had ‘Lotta Love.’”

Larson made another attempt the following year with Rose of My Heart, with the cover art featuring the musician in a black blouse with embroidered flowers and a red scarf around her neck. She got a bite with “That’s How You Know Love’s Right,” her duet with Steve Wariner, which peaked at Number Nine on the country charts.

Wariner was riding high on his album Life’s Highway, with three hit singles on the charts. He was familiar with “Lotta Love,” and quickly said yes to a collaboration. They spent an hour recording at Back Stage studios, and the two hit it off. “We immediately became friends,” Wariner says. “She was so sweet, but she was like one of the guys — right in the middle of the room, laughing, joking, and having fun. She wasn’t a diva, you know what I mean?”

The duo performed the sultry ballad on television, including a March 1987 appearance on Hee Haw. Wariner remembers being completely transfixed by her onstage: “I don’t talk about this much, but, boy, when she was singing, she’d look right at you,” he says. “Honestly, I can see myself being uncomfortable with her in some clips, because I was like, ‘Damn, she’s so pretty. Oh, my God, she’s singing about how much she loves me. OK! I’ve got to think about trees and rocks, or something!’ She had really great pitch and control.”

And yet, Larson failed to successfully cross over. Many have stated how difficult it is to break into the country scene, including Rodney Crowell, who suspects it would have taken more than one song. “It takes a while before you would be allowed in, and I don’t necessarily think that Nicolette was naturally a country singer,” he says. “I don’t think her mindset and her sensibilities were really geared toward what the gatekeepers of country music would project on her.”

Brown says that while Larson never complained about her lack of success, she remained puzzled. “She would ask me, ‘What is the problem? Is there something I should be doing?’” he remembers. “I really thought she was a special person and I really loved her voice. I was really disappointed that it didn’t work. As a record executive and a producer, I felt I let her down, and I’m sure she probably felt she let me down. Now that I’m older and wiser, I just realize, if the stars don’t line up, it’s just not going to happen. They got to line up.”

Larson’s stint in country is so little-remembered that neither album is on streaming services. They were only released on CD once, as a compilation in 2012, and copies usually sell for upwards of $100 on the internet. “When I hang up,” says Brown, “I’m going to go to eBay and see if I can find that damn record.”

She returned to pop with 1988’s Shadows of Love — released exclusively in Italy — and attempted to act, appearing as the bar singer performing with Jeff Beck in Twins, starring Danny DeVito and Arnold Schwarzenegger. But as she moved into the Nineties, something happened to Larson that made her struggling career her second priority: She became a mother.

Elsie May is at her home in Big Tujunga Canyon in the Angeles National Forest in February, using a landline because the cellular service is weak and she’s “perpetually in 1995.” She’s currently in Larson’s flannel, which she wears on hard days when she wants to feel close to her mother.

Like her parents, May is a musician — she just returned from a songwriting retreat with her husband and bandmates — and her resemblance to her mother is so striking that it proved difficult at first. “People would be like, ‘Why don’t you just play her songs?’” she recalls. “I got one horrid comment on a YouTube page at one point that was like, ‘You should just wear your hair and braids and play “Lotta Love” and it would be like Nicci never died.’ I was like, ‘Oh, God! Ouch!’”

Pinpointing exact dates is challenging for May — she was only seven when Larson died — but pockets of memories are dear to her. She remembers Larson singing to her each night, strumming her Takamine guitar, and how May was able to fit into the instrument’s case and fall asleep. She remembers being a part of the photo shoot for Larson’s 1994 lullaby album, Sleep Baby Sleep, and suggesting to her mother that she title a song “Oh Bear,” after her teddy. She remembers Larson taking her to school one day, only to surprise her by driving to Disneyland instead. She remembers playing solitaire and puzzles in front of the fireplace, snuggled up in blankets. And she remembers saying goodbye to Larson when she was on life support, laying in bed next to her at the UCLA hospital, just before Christmas 1997.

Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Despite both being part of the Seventies Southern California rock scene, Larson and Kunkel didn’t actually meet until the end of the decade, and didn’t begin dating until the late Eighties. “We had been orbiting each other for years, but there was never an opportunity for us to spend any time together,” says Kunkel, whose legendary drum credits range from Joni Mitchell to James Taylor to Bob Dylan. “That was the time.”

Like every subject interviewed for this article, Kunkel emphasizes Larson’s personality — effervescent, charming, and humorous. “If she walked into a room, everybody just felt better,” he says. He also notes her obsession with Christmas, and how she once left their tree up for two straight years. “Nicolette said, ‘It’s a fake tree, what the hell? And every time you come in the house, you look at it and go: Oh, man, I feel better, it’s like Christmas is coming!'”

Despite being a natural onstage, Larson was happiest at home. She was usually in her pj’s — wearing a blue robe that May remembers having stars and moons on it — eating sugar-free popsicles, reading books, and watering her plants. “She was just a really cool lady that wanted to relax at home and do boring stuff, you know?” May says.

Larson told The Kansas City Star as much in 1984. “There’s a lot of times when I’ve been backstage before a show and I look into the mirror and I don’t want to do it,” she said. “I feel like looking at that image of myself and saying, ‘You go out and do it and I’ll stay here and read a book, and I’ll be here when you get back.’”

When Larson became pregnant, Kunkel dropped a ring into a champagne glass at lunch. “It wasn’t really traditional,” he says. “It was a mutual decision that was the best thing for us to do.” They were married at the Intercontinental Hotel in Maui, and May was born in 1990. Larson appointed Ronstadt as her godmother. “Nicci wanted a baby so badly, and she was so happy when she got Elsie,” Ronstadt says. “They were little buddies.”

Two years after May was born, Young recruited Larson for his new album Harvest Moon. They briefly worked together during the previous decade when she opened for Young’s International Harvesters in 1985, but this would be their first time reuniting on a record. Young also invited the same Comes a Time musicians to play on the new album, including Keith, Oldham, and Drummond.

If the heartwarming folk on Comes a Time harked back to Young’s Harvest era, Harvest Moon was revisiting that sound once again. It proved that at nearly 50 years old, Young was still capable of capturing that blissful barn-dance vibe, ushered in by Larson’s harmonies on “War of Man,” “Such a Woman,” and more.

Ronstadt and Young’s half-sister, Astrid, also supplied backing vocals; although Ronstadt is credited for singing on the title track, it’s Larson and Astrid in the video, ooo-ing along onstage with Young as he sings his love song for his then-wife, Pegi. It was Astrid’s first time recording with her brother, and Larson became her mentor.

“She really took me under her wing,” Astrid recalls. “Linda set a bar for us in the Harvest Moon recording because she held a note for an insanely long time. And I basically said, ‘There’s no way I can hold that note for that long.’ [Nicolette] goes, ‘Yes, you can. I’m going to show you.’ She taught me the technique and I instantly was able to do it. She did not take any of my insecurities for an answer, and probably had more faith in me than I did at the time.”

A year later, Larson came to Astrid’s aid again, during the taping of Young’s Unplugged, when he changed the set list at the last minute. “A lot of songs in the set we had never rehearsed, and I didn’t know the parts,” she says. “[Nicolette] was basically singing my line to me in my ear in between parts. When they cut away to us in the video, we’re just pulling back to our mics. She always had this ‘soldier on’ attitude about anything, and I really looked up to her for that.”

Astrid kept in touch with Larson over the next few years, going hiking with her in Runyon Canyon and seeing bands at the Viper Room. Eventually, though, Larson started to flake on plans. “She would invariably cancel on me,” Astrid says. “‘Oh, I think I’m just going to stay home and have a glass of wine and a Valium, and take a bath and go to bed.’ This happened more times than I can count. The first couple of times you don’t really think about it too much, but then it turns into a pattern.”

Despite the joy that came with motherhood, many have noted how withdrawn and depressed Larson was in the remaining years of her life, particularly with Kunkel often out on the road. “Elsie was the light of her life, and she loved Russ very much,” Astrid says. “But I don’t think she really expected to be alone quite as much as she was.” Joel Bernstein agrees: “I think the marriage was difficult for her, and I just wish that her last years had been happier ones.”

Courtesy of Elsie May

Kunkel acknowledges that as two working musicians, he and Larson definitely had to spend a lot of time apart. But even at home, Larson requested they have separate bedrooms. “We were living together raising a child, but were also like roommates,” he says. “Whatever part of depression that our relationship contributed to her well-being, it was what it was. I loved her dearly. I just can’t say it any other way.”

Several sources have speculated that Larson’s use of Tylenol, wine, and Valium contributed to her death, but the truth is much more complicated than that, beginning with the fact that she rarely went to the doctor. “She was not one to go get checked up for things regularly,” May remembers of her mother. “Which, in turn, I am the exact opposite now.”

To Kunkel and May, Larson’s death is a blur, a tragedy that unfolded in just a week. After having flu-like symptoms and drinking protein shakes to soothe her stomach, she finally agreed to visit Providence Saint Joseph Medical Center in the San Fernando Valley. She was diagnosed with liver damage four days later, and was transferred to UCLA Medical Center for a transplant. David Crosby, who received his own transplant in 1994, warned Kunkel the waiting list would be extremely long. “He was honest with me about that,” Kunkel says. “Even though it might have been a long shot, I was going to try anything.”

At UCLA, they discovered that Larson had an ulcer, and in that process she had a seizure, which put her into a coma. “It happened quickly, one event right after the other,” Kunkel painfully recalls. “When she was in the coma and her brain started to swell, the doctors came in and they had the conversation. ‘We’ve done all the tests.’ You’re left with that horrible choice of whether you keep somebody alive on machines or you let them go.”

Larson died nine days before Christmas — her favorite holiday — of a cerebral edema. “The doctors did everything in their power to save her, but sadly they could not,” her friend Graham Nash told The Kansas City Star. “It is a very sad day for music.”

A funeral was held at Forest Lawn Memorial Park in the Hollywood Hills. Templeman didn’t attend (“I couldn’t have made it through it”), and Bernstein remembers that attendees were sobbing well before the service began. “It was just so tragic that she was gone,” he says. “I remember looking at that coffin and thinking, ‘OK, Nic, this joke has gone far enough. Just get out of the fucking casket, all right? We can’t deal with this anymore. Just fucking get up and get out of the fucking casket.’”

An all-star tribute concert was held for Larson the following February at the Santa Monica Civic Auditorium, featuring Ronstadt; Crosby, Stills, and Nash; Bonnie Raitt; Jackson Browne; Carole King; and others. “The people that knew her really, really were intent on bringing the most they could to dedicate to her spirit at that moment,” Bernstein says.

May mostly remembers playing hide-and-seek with her cousins in the green room, while wearing a sunflower shirt with matching leggings. “I remember being backstage and Joe Walsh gave me a hug,” she says. “It’s so funny saying it out loud, all these big names. But to me it was just more aunts and uncles.”

Young’s absence at the tribute was felt by many, including him. “I just couldn’t do it,” he says. “I just didn’t want to go. Because I have my own memories of her, and I just felt like I couldn’t do it at that time. But now I would like to say how great she was, and what a wonderful person she was.”

About a year ago, Kunkel stopped by May’s and gave her some of her mother’s belongings. “[He was] like, ‘Hi, you’re in your thirties, you’re married, you have a mortgage,’” she recalls her father saying. “’You can be responsible for her wedding ring now.’”

Kunkel thinks that had Larson lived, they’d still be married. He also admits that after nearly 25 years, he’s still grappling with her death. “I think in a lot of ways, I’m still processing it,” he says. “We carry trauma until we work [it] out. We carry those things with us. I’m a functioning processor. Let’s put it that way.”

The same goes for the 15 sources interviewed for this story. All these years later, they’re still trying to make sense of Larson’s death. “I wish I could go back in time and redo my Nicolette Larson experience,” Tony Brown says of her failed country career. “If that was now, I probably would’ve started a Highwomen [with] Nicolette and Emmy, like Brandi Carlile did.” Rodney Crowell regrets losing touch with Larson after she divorced DeVito: “When Nicolette passed away and I ran into Russell, I said, ‘God, you’re having your own grief and I don’t want to dump this on you, but I feel like as a friend, I let Nicolette down.’”

Others still marvel at how Larson touched their lives. For Astrid, she thinks of Larson every time she sings. “You meet people in your life that make a huge impact on you, and that’s never going to go away,” she says. Kunkel feels he’s grateful for their time together, however brief. “We were blessed to be on her journey for that short seven-and-a-half–year period,” he says. “Her story is so much bigger than me, anyway.”

“She was so much more than ‘Lotta Love,’ even though she had a lot of love to give,” May adds.

Beyond music, May is carrying on her mother’s traditions: She recently left her artificial Christmas tree up well past its due date. “I haven’t taken it down yet,” she says proudly.

Best of Rolling Stone