Love the Songwriting of Jason Isbell and Robert Earl Keen? Credit Cormac McCarthy

For a writer who spent most of his career outside the limelight, the outpouring of public admiration in the wake of Cormac McCarthy’s death on June 13 at 89 testified to the power of his work. An obscure figure with a cultish following for much of his writing life, McCarthy had long been esteemed by members of the literati. The late literary scholar Harold Bloom placed him on his very short list of American authors in the 20th century who had in their writing achieved the sublime, naming him alone as “the true heir to Melville and Faulkner.”

Nearly three decades into his career, McCarthy found mainstream success with the publication in 1992 of his Western epic All the Pretty Horses. Later, he would achieve greater renown when the Coen Brothers’ film adaptation of No Country for Old Men won the Academy Award for Best Picture in 2008. But it was his 2005 parable about a father and son navigating a post-apocalyptic world, The Road, that first catapulted him to household-name status, winning him a Pulitzer and landing him on Oprah’s Book Club list. More recently, in 2022, McCarthy released two companion novels, The Passenger and Stella Maris, a suite of stirring swan songs that stand as a fitting coda to his challenging and brilliant body of work. On the day of McCarthy’s death, Stephen King said that he was “maybe the greatest American novelist of my time.”

More from Rolling Stone

Jason Isbell Unveils 2023 Ryman Residency with Guests S.G. Goodman, Lawrence Rothman

Cormac McCarthy, Novelist Who Explored an Apocalyptic American West, Dead at 89

Jason Isbell Hits a Brutally Beautiful Songwriting Peak with 'Weathervanes'

But for all the merits of his art, it was the “American language,” as historian Shelby Foote once put it, that was perhaps the true star of his novels. McCarthy wrote in cadences that many likened to the King James Bible (though much of his late work was marked by a more stripped-down prose style approaching that of Beckett). McCarthy’s imagery is strikingly visual and the rhythm of his prose has a sonority to it that, when read aloud, flows like music and puts most capital P poets to shame.

Perhaps it is no surprise then that among the hosannas following the news of his death, something interesting began to emerge: The prose-poet of Homeric proportions had left his mark on songwriters and musicians too. Social media was dotted with tributes from those in the music world who felt compelled to acknowledge McCarthy’s influence. Songwriter Jason Isbell, who’s talked before about his reverence for the Tennessee-bred author, might have said it best: “How many of us did he influence? Immeasurable. I could go onstage and say ‘this next one was influenced by Cormac McCarthy’ and literally sing any song I’ve ever written.”

Bruce Springsteen has checked McCarthy among his favorite writers, telling the New York Times in 2014 that Blood Meridian was a “watermark” in his reading. The Road, he added, was the last book to make him cry. And McCarthy is also a darling of Tom Waits, who apparently was hipped to the writer long before the author’s mainstream arrival. Nick Cave, who helped compose the score for the 2009 film adaptation of The Road, also counts himself as an admirer. “It’s clever, that book,” Cave told Radical Reads in 2018, “because the environment that they’re living in is so unremittingly pessimistic that he’s able to weave this extraordinarily sentimental story about the love between father and son and completely get away with it.”

Hataa?ii, a 20-year-old Navajo singer-songwriter from Window Rock, Arizona, whose new album Singing into the Darkness came out last month on Dangerbird Records, tells Rolling Stone that his worldview had been shaped by the novelist.

“Because of McCarthy I figured out that the desert was more than just a void, but rather it was filled with spirit and that the people who truly live in the desert see things differently,” Hataa?ii says. “There was a sudden appreciation and immense respect that I now held for the history of the area and even the landscape formations, which saw me and every other generation that came before me, and that I was simply in line with my ancestry and that me and my ancestry were the same thing.”

Texas singer-songwriter Robert Earl Keen is something of a Cormac super-fan and collects first editions of his novels. He once had designs on purchasing McCarthy’s Olivetti Lettera 32 typewriter, which the novelist had used to write all his novels, when it went up for auction at Christie’s in 2009. Keen was prepared to spend $50,000 but bowed out after the bidding hit that figure in no time. “It shot through 50 like butter, man, like boom!” Keen tells Rolling Stone. It ended up going for nearly a quarter-million to “some guy in a blue raincoat, like in the Leonard Cohen song,” he says with a laugh.

McCarthy’s influence found its way directly into Keen’s songwriting. His 1998 album Walking Distance contains a five-song concept piece that loosely tracks the trails of The Kid in Blood Meridian, from the eastern United States into Texas and then down into Mexico. He wrote the songs in the first-person and set them in the present day, as opposed to the mid-nineteenth century when the novel takes place.

It’s the imagery in McCarthy’s prose, Keen says, that’s inspired him most. He mentions McCarthy’s first novel, The Orchard Keeper (1965), as an example. “He’ll talk about some steps going up to the porch, and how the moss is a certain color and it’s still sort of moist and it gives you that feeling that you’re really back there in the shadows in eastern Tennessee, and how cold it is and wet it is, at the same time without ever really saying it’s cold and wet — he’s just talking about the moss. He taught me that it’s about the importance of the imagery within a piece of writing, or even a song, and does the imagery mean anything in and of itself, no matter if it seems off-track.”

As a devoted reader of McCarthy, Keen is also in awe of his “narrative [gifts] and that ability he has to make a story that doesn’t have a real obvious trajectory,” he says. “And the stories never really wrap up. Time just sort of continues … I have to say he’s really spoiled me as a reader, so I just keep re-reading his books. Other than Henry Miller or even Emerson maybe, I never found writing like his that really grabs me and makes sense to me.”

McCarthy’s most pronounced influence on the American songbook comes in the form of The Last Pale Light in the West, a 2009 album inspired by Blood Meridian that was written and recorded by Ben Nichols, best known as the frontman for Memphis rock band Lucero. The album features seven story-songs based on different characters from the novel (“The Kid”, “Toadvine”, “Chambers,” et al.), set to acoustic guitar, pedal steel, accordion, and piano.

“If I had set down to write a concept album about a Cormac McCarthy novel, well, that just sounds terrifying,” Nichols tells Rolling Stone when asked about the chutzpah it must have taken to translate a novel like Blood Meridian into song form. “Just doing it piece by piece by accident, just for the love of the words [is how it happened] … I wanted my dad to hear it. He’s a big Western fan. And so I put together these little short stories to songs, taking snippets out of the book and putting them to music. It just started as a little project to amuse myself. If I had known what I was actually pursuing, I might not have done it.”

Nichols says there’s a reason McCarthy’s work speaks to songwriters. “I wasn’t always a big poetry fan, but I’ve come around some in my older age. But Blood Meridian always sounded like poetry to me and the way I wish more poems sounded. It has that lyrical quality and it’s in the cadences and the rhythm of the language. For the last 20 years Cormac McCarthy has functioned as my go-to poet, even though he’s writing prose.”

But it wasn’t just the language that appealed to Nichols. It’s also the truths embedded in the poetry, and the sheer daring of this singular artist. “Blood Meridian still my favorite novel,” he says. “I respect McCarthy for tackling such a soaring epic that was really reaching for the stars and dealing with some really fundamental human concepts, and doing it not ironically at all.”

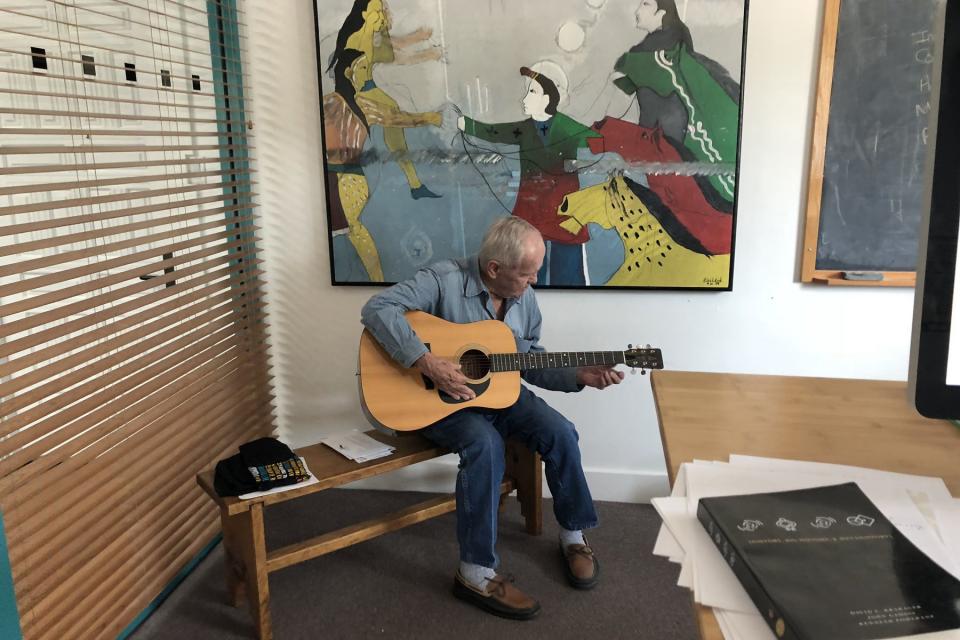

Shortly after McCarthy’s passing, the Santa Fe Institute, the theoretical research nonprofit where McCarthy was a trustee and kept an office for decades, posted a photo of the writer holding an acoustic guitar in the SFI office.

John Miller, a research fellow at SFI, tells Rolling Stone that “Cormac had an encyclopedic knowledge of song lyrics — you could ask about any old song and he would know the lyrics and melody. Though in all our conversations over the years, I never heard him say anything about how a song was based on his writings.”

SFI’s obituary for McCarthy said he could also “sing and play a folk song” after a single listen. I mentioned this to Nichols and he wasn’t surprised. “That might be the Tennessee coming out in him,” he says. “He’s one of those guys, probably like Bob Dylan, he probably knew the Alan Lomax catalog of field recordings back and forth. I can see folk music being a giant influence on McCarthy’s writing in numerous ways. You combine the King James Bible and the folk tales and the mythology and you put it all in a cauldron and mix it up into a brew, and you throw in a dash of science and philosophy, it’s going to be good, if it’s written well.”

In the cosmos of McCarthy’s novels, music often occupies a place alongside the sacred, among the mysterious rites. Blood Meridian and Stella Maris in particular enjoin it with the primeval, timeless forces that precede our own human origins. Judge Holden of Blood Meridian is one of the most complex archetypes of human villainy ever written — on the stock of his rifle is inscribed a line from Virgil, “Et in Arcadia ego” (“I too was in Paradise”) — and McCarthy ensures he bears more than a passing resemblance to the Satan of Milton’s Paradise Lost. Like many presentations of the devil from the 17th century onward, the Judge, who may or may not be Beelzebub, is a fiddle player. The final scene of the novel finds him in a Texas saloon, floating naked and barefoot across the dancefloor, “dancing and fiddling at once.”

Blood Meridian dives into the cosmic dark with a searchlight, and the great questions raised in Stella Maris offer a similar probing. Here, the character Alicia Western seems to echo many of McCarthy’s views regarding the human condition. Hers is one of the few minds on Earth that can grapple with the questions at the heart of quantum physics, and tellingly, it is music that she holds aloft when reflecting on the universe’s deeper mysteries. A violinist of the highest order, she plays an ancient Amati, paid for with the sum of her family inheritance.

The allegation that McCarthy’s work presents a certain nihilism is superficial. It requires a wholesale denial of the human kindnesses and tender mercies throughout his books, and the moral perseverance exhibited by so many of his characters.

If McCarthy is a nihilist, he is not a very good one. “Nothing smells like a three hundred year old violin …,” Alicia Western says to her psychiatrist in Stella Maris. “I tightened it and then I just sat there and started playing Bach’s Chaconne … I started crying and couldn’t stop… And I remember saying: What are we? Sitting there on the bed holding the Amati, which was so beautiful it hardly seemed real. It was the most beautiful thing I’d ever seen and I couldn’t understand how such a thing could even be possible.”

Nichols says he called his album The Last Pale Light in the West for a reason. The Lucero singer says there’s a flicker of hope — along with wallops of humor, heartbreak, and empathy — in McCarthy’s books. He cites the fire Sheriff Bell’s father builds in a dream amid all the darkness and cold at the end of No Country for Old Men, or the man in the yellow parka who finds the child at the end of The Road after the father dies, or the last pale light glimpsed by The Kid as he comes upon the end of his own journey in Blood Meridian. “It might be small but there is always a light to follow somewhere out in the darkness,” Nichols says. “That’s something I always liked.”

In McCarthy’s work, music functions as one of the last pale lights in the void. Perhaps nowhere is this more evident than when the child in The Road whittles a flute from wood. It is a moving episode that signals a moment of fleeting joy amid the ashen desolation of his world. “The man thought he seemed some sad and solitary changeling child announcing the arrival of a traveling spectacle of shire and village who does not know that behind him the players have all been carried off by wolves,” McCarthy writes. It is an image that has its antecedent in McCarthy’s 1979 Suttree, for there, the novel’s namesake whittles a flute while sitting alongside the river, his life ghastly and nearly bereft of all hope, and yet he plows on.

In her disquisition to her psychiatrist on the nature of music, the kind of monologue for which McCarthy is known, Alicia Western says: “Music is made out of nothing but some fairly simple rules. Yet it’s true that no one made them up. The rules. The notes themselves amount to almost nothing. But why some particular arrangement of these notes should have such a profound effect on our emotions is a mystery beyond even the hope of comprehension.” May we continue to nurture that mystery. McCarthy would have it so.

Best of Rolling Stone