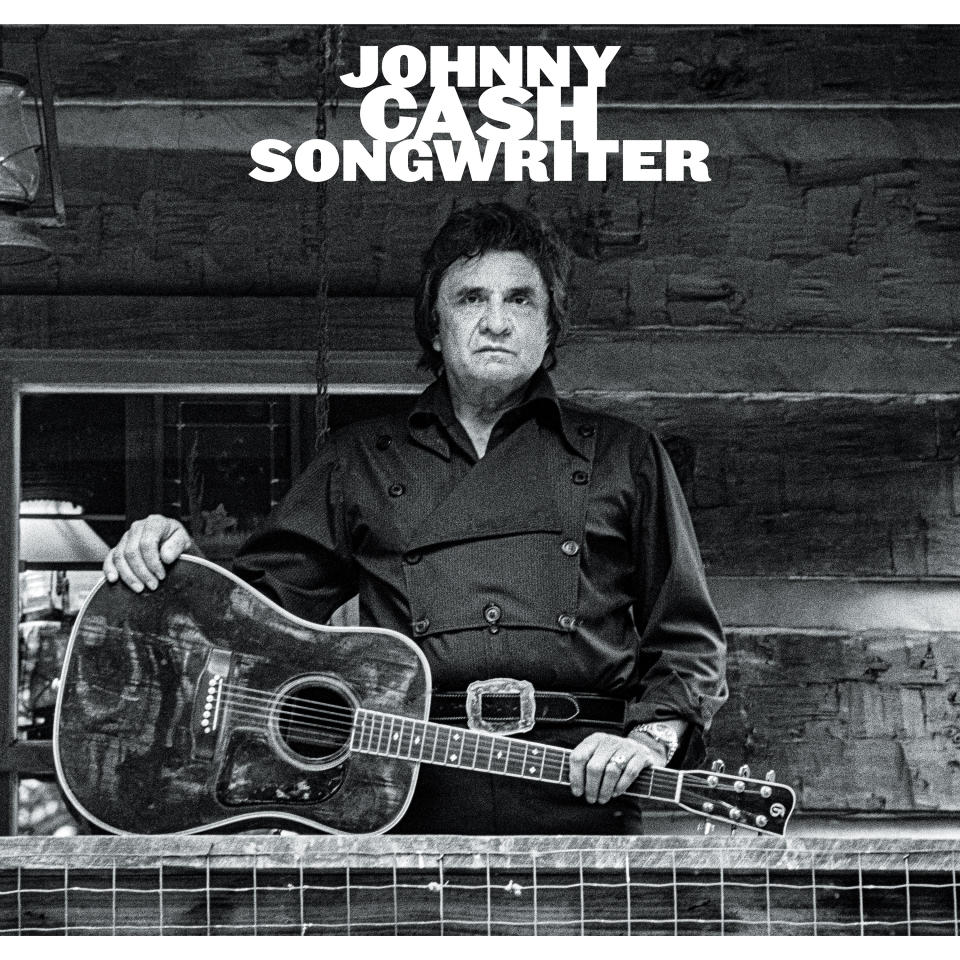

The Making, and Remaking, of Johnny Cash’s ‘Songwriter’ Album: How John Carter Cash, Marty Stuart and Others Brought the Icon’s Buried Treasure Back to Life

Very few people would have guessed that we’d be getting an album of previously unreleased original material from Johnny Cash in 2024 — a collection that really feels like a “new” album from the legendary singer, 21 years after his death. Far fewer still bet on anything coming out at this late date would be any good, if the original recordings sat in the vault this long. So “Songwriter,” which came out Friday, registers as a real surprise on every count. It offers a Cash who not only sounds like he’s right there in front of you, in his fullest, richest voice, but trotting out a batch of completely self-penned songs so strong it’s hard to believe he didn’t release them in his lifetime.

The new album’s co-producers, John Carter Cash and David “Fergie” Ferguson, spoke with Variety about where the project came from and how it got reinvisioned for the 21st century, as did Marty Stuart, the Country Music Hall of Famer and close friend of Cash’s who went into the studio to record new guitar parts for the set.

More from Variety

Grand Ole Opry to Celebrate 5,000th Weekly Broadcast in October

Unreleased Live Johnny Cash Album From 1968 Due in September

They explain how Cash went into a studio with members of his touring band in 1993 and quickly recorded these 11 demos of songs he’d recently written, and then set the recordings aside as he soon moved on to a highly fruitful collaboration with Rick Rubin. Two of the 11 compositions Cash played for the first time in that ’93 session, “Drive On” and “Like a Soldier,” did end up getting picked up and re-recorded by Rubin for the comeback albums he produced. But the other nine never saw daylight again in any form until now, and there are some real gems among them, including some highly personal material he wrote about his relationship with June Carter Cash and her family.

Over the last few years, Cash’s son, John, and “Fergie,” who’d engineered the senior Cash’s albums since the early 1980s, came together at the famous Cash Cabin outside of Nashville and invited players in to record new backing tracks for the 11 tunes, to replace original arrangements that everyone involved agreed felt under-rehearsed or dated. Here, captured in separate interviews, Cash, Ferguson and Stuart offer a history of the project, from 1993 to now, along with thoughts about Johnny Cash’s legacy as a tunesmith.

Where was Johnny at when he laid down these tracks? Since this was before his fateful hookup with Rick Rubin, was he down at all from the downturn his recording career had suffered in the ‘80s?

John Carter Cash: He was sort of in limbo, just before he was cool again, I think. He had just done the stuff with U2 [singing lead on “The Wanderer,” which appeared on the band’s 1993 “Zooropa” album], but I don’t think that was released yet at this time. So he was on an upswing, but it was before he had officially left Polygram and before he was officially with Rick Rubin. He may have met Rick, but he was still not under contract. So he was considering songs, for what he might do possibly with Rick.

When he recorded this, with the way that it was recorded, I don’t know if he ever intended on it being a quote-unquote album. But when you have these amazing vocals and the great presentation of all original Johnny Cash songs, and his guitar, that’s what we had. The question was, how do we under-produce it, to let it be an album that that works in a way that’s right, without being trite, and add the music that he would’ve added if he was here?

Two of the songs wound up on the “American” series. “Drive On” was on the first American record, but there it was just done with him and a guitar. Some of these were fun things that were just sort of silly, like “Well, All Right” [a song about hooking up with a woman at a laundromat]— those weren’t the kind of songs that he would consider for a record with Rick Rubin. But this works as a body of work, because it shows all these different variances of who he was as a songwriter. If you look at the styles of songs that are on his greatest records, that they’re the ones that are on this album — the same style of songs that are on “American 1” or “American 4” or the live records for that matter, like “Folsom.”

The quality of his voice knocks you down. So if I ever questioned whether the record should be released, then hearing the tone of his voice and the power of his presentation at this point in his life… He was in a great space. He was clearheaded at this time. He was in recovery. He was connected with family. He was in healing relationships when he made this album.

Marty, you were in his band in the ‘80s, but gone from that circle by the time of this session. Did you know about these tapes?

Marty Stuart: I wasn’t aware of these songs or sessions. I think it was during COVID that John Carter called me and told me the story: “We’ve rescued these tapes, and some of the songs are pretty good, but we’re gonna take it down and build them back up.” So I went to Cash Cabin, and I think me and the engineer were the only two people there. The goal was to take it down to the voice and the guitar. And some of John’s guitar parts we could use and some we didn’t. But the thing that that first struck me was hearing that voice and being like, “Well, there he is. Oh, geez.”

Hearing his voice on this is kind of startling, if you’re thinking it is going to sound like he sounded on “Hurt” — it’s so robust.

Stuart: What I loved about it the most is that he sounded so healthy and vibrant and there was so much fire in his voice. As the guitar player in his band in the ‘80s, the thing about playing with him is that voice was like this big oak tree. You could take anything you threw at it and it never moved. There was a power about it, and it had a thousand different colors inside of it, and nuances of tone, that all he did was just open his mouth and there it was, but it was a great voice to play to. … So it was great to have him back in the room. It was a great visit. I left the studio stepping higher, because it felt like I’d hung out with the chief.

David “Fergie” Ferguson: When you hear his voice on this, it really sounds like it could be to me like Johnny Cash in the late ‘60s or ‘70s. Johnny Cash was a man of many voices. I’ve discovered, there’s this voice from the mid-‘50s, where he sounded different — it’s not as resonant, or wasn’t as matured. The voice that we have here is the one that caught on with him in the late ‘60s and ‘70s, I think, when it kind of mellowed, when he had “One Piece at a Time” and “Blistered” and those kind of things.

What was wrong with the backing tracks on the original tapes, that you felt you needed to replace them? Did they just sound dated?

Ferguson: His voice was in great shape the day he made these recordings. He sounded like he felt really good. But what he did is he would sing the song, get the band to play along with him, and sing until he thought he had gotten it all out without stuttering or making a mistake. And they’d say, “OK, let’s move to the next one.” So therefore, the band wasn’t as good as it could be — kind of really not very good. I think the band members that were on the original recordings would want them redone. They’d say, “We’d love to have another crack at it,” but most of ’em are gone. So it was not a matter of the arrangement sounding dated so much as just the performances weren’t what they needed to be.

Cash: There was gated drums, and a lot of harmonica, albeit a great harmonica player. To me, it was of the time. I think with the tones of the upright bass, it wasn’t played that well. Dave Rowe was not as great a player back then when he first did this recording. So when Dave came back all those years later, and we added him at that point, after all those years of him playing on sessions and working with my dad, he was one of the best bass players in Nashville. But when it was first done, he wasn’t playing as well as he did later.

My father’s voice is timeless. His guitar is timeless. The recordings, though, were of the time, including that one rhythm guitar player that was on most of it, who happened to be me. So I took me off — I’m also one of the musicians that was removed.

My favorite song on the record is “Spotlight,” which is just classic country songwriting. It doesn’t hurt that you enlisted Dan Auerbach for a solo.

Fergie: I work a lot with Dan, and I played “Spotlight” for him. He said, “Man, I’d love to play on that.” And I said, “Well, there’s nothing we’d like more.” So that’s one where we did change the arrangement and add some space in there for him to take that solo. He really enjoyed it and then he played some licks on the end of it. It fit Dan’s style really well. I hope everybody else thinks so, too. Dan is so proud. He sent me a picture of the title coming up on the radio on the dash of the car, where it said “Johnny Cash and Dan Auerbach” on the same line. He said, “Man, I can’t believe it.”

“Spotlight” has kind of a little rock groove and it seemed to really fit what he was singing, or what he was feeling when he wrote it, I think. And what was on the original tape was nothing like that — it was not good. But some of ’em, we kept really kind of true to what was to the tape too, like “Well, All Right.” That and a few others are straight-up Johnny Cash beats, and so we didn’t mess with the man’s beat too much on those. Some of them we had to add a bar here and take a bar or two out there to make ’em make more sense.

Cash: “Spotlight” was so short, in its original form. We wound up doubling the chorus because it was just like a minute and a half. I was like, there’s got to be more.

Do you have a favorite song on the new record?

Stuart: I really love “Drive On” a lot. But there’s a song called “Soldier Boy,” and there’s a reason I love it. Everybody has their favorite version of Johnny Cash. But you know, that Johnny Cash from the late ‘50s, early ‘60s when it was Luther and Marshall and him — the Tennessee Three was my Beatles. And that character who was making records from then right along about up to the “Folsom Prison” live album, that was my favorite. So when I heard “Soldier Boy,” John Carter owns one of Luther Perkins’ guitars, and I said, “Let me have Luther’s guitar,” and I rolled all the tone off of it so it would sound like he did on “I Walk the Line” and “Give My Love to Rose.” All of a sudden that Johnny Cash that I fell in love with as a kid reappeared in my speakers when I framed it in that sound. So if I had to point to one song on this record and go, “That’s the one I want to put in my pocket,” it would probably be “Soldier Boy,” for that reason.

Fergie: I think my favorite, or one of my favorites, is “She Sang Sweet Baby James.” That’s some real gut-wrenching, beautiful Johnny Cash songwriting.

Where do you think his songwriting legacy stands?

Stuart: Merle Haggard and I used to talk about John’s songwriting and one day we went, “All right, we have to pick a favorite.” I said, “Yeah, that’s like picking one of yours as a favorite. You can’t do it.” But somehow we settled on “Five Feet High and Rising.” That would’ve been from the late ‘50s. And it’s like, man, that is one of the most perfect songs ever written, everything about it, and it defined him. And there’s an obscure song that he wrote in about ‘65, called “The Walls of a Prison That Nobody Knows.” It was buried on a record called “From Sea to Shining Sea.” The tune is (borrowed from) “The Streets of Laredo,” but the words are just incredible. So no, he was never, ever, ever to be taken lightly as a writer.

Fergie: He could be a silly, silly man. That guy, he was just fun… When I was working with him in the ‘80s, he’d go up to the studio and Cowboy (Jack Clement) would say, “Ferg, go up there … Johnny wants to do something.” I’d go up there and put a couple microphones on Johnny and turn on the little quarter-inch tape machine, and he would put down some silly song that he had written that morning. There was one called “Wackos and Weirdos” that came out on a record later, and the chorus was, ”There were wackos and weirdos and dingbats and dodos and movie stars and David Allen Coe / There was leather and lace and every minority race with a backstage pass to the Willie Nelson show.” It was talking about all these nuts backstage at a Willie Nelson show. And one of my all-time favorite songs of his is called “Beans for Breakfast.” And I mean, it’s a piece of work. It’s got the word “histoplasmosis” in it. That ain’t a word you hear in songs.

Looking back on this time, in ’93, do you think he had this confidence about himself that things were going to turn back in his favor, or did it really take working with Rubin a bit later to get there?

Stuart: I think it was a time where, if you knew where to look, you could tell that the telegraph was kind of clicking in his favor. Like, man, this is gonna pop again. You know, he is one of those characters. He always comes back around. And it hadn’t quite happened yet, but there was enough evidence on the table to know that this is gonna happen again.

When I was in the band, you know, we would play a lot of concerts and he was like Patriot Cash to older citizens in the heartland. And a stray rock star would come by every now and then. He would fill up state fairs and performing arts centers. But when we would go to Europe, that’s when I would see what could potentially happen, because all the rockabilly kids came out and pop stars came out, and he was still a pop star over there. I went to him after a show one night and I said, “Why don’t you fire me and everybody else on this stage that couldn’t have anything to do with your real sound? That’s what people are longing for out of you.” And he says, “A lot of people depend on me.” I said, “I get that, but there’s a day coming that you’re gonna have to address this.”

And a few years not long after that, in the ‘90s, he called me to his office one day and he said, “Have a seat.” And he opened a Coca-Cola and he handed it to me. He said, “Don’t talk to me for 21 minutes.” I laughed and said, “OK.” And he sang me 10 songs in a row, just him and his guitar. And at the end of it, I said, “What did I just hear?” He said, “My new record with Rick Rubin. What do you think?” I asked, “It’s just you and your guitar?” He said, “Yep.” I said, “I think it’s brilliant.” And that became that first “American Recordings.” It was just a matter of getting it back to square one and turning the wheel just in enough where the world saw it in a different light. And I loved it for him. Couldn’t have been happier.

Ferguson: I like this record being in-between the stuff from the ‘70s or ‘80s and the Rick Rubin era. It has its own sound. And, God bless Rick Rubin. I love Rick. Rick single-handedly brought that man back from the doldrums of not getting any airplay at all or nothing going on, and turned it around for him, and was very respectful and kind to Johnny. He did Johnny right, and Johnny loved the guy. But this is just a bit prior to that. And John Carter and I had some freedom, and we took it. I’d never been able to make a Johnny Cash record where I wasn’t working for the producer, so it’s kind of nice.

He was in a really good place also because he was doing the Highwaymen during this period, and he enjoyed that. Those guys loved each other. But yeah, Johnny was happy, man. He was. You can tell. I can tell he is happy in those recordings. I can tell he feels good. I can tell he’s sober. I can tell he wanted to be there.

You know, that guy loved to sing. I’d be sitting in a room with him, sitting there talking. I said, “Hey, sing a song, JR.” And he picked the guitar up and would sing a song in a second. Or my mother or a friend would walk in, and I said, “Hey, that’s Johnny Cash. You want him to sing a song?” And Johnny would grab that guitar and just sit there and give you the most beautiful performance. I get chills just thinking about it, you know? Because I loved it when it was happening and I’m so glad to have been there to listen to it. To hear the tone coming out of that guy’s head, you know, it’s crazy. And this record is the period that is really my favorite period of his singing voice.

Do you think he valued his songwriting as much as everyone else did? He didn’t fill his own records with his own songs, which makes this one unusual. The “American Recordings” albums that reestablished him were mostly covers, although “The Man Comes Around” became one of his most iconic songs.

Cash: A song like “Well, All Right” on this is just him having fun. My dad, he wrote a lot of wonderful things, and then he wrote some songs that weren’t quite as good. There are other writers that were more consistent in writing these masterpieces. Dad wrote some things that weren’t quite masterpieces sometimes, but there are the masterpieces there within the catalog.

He never wrote a song because he felt like it was time to sit down and write a song. If he wrote a song, it was for fun or for healing or for education. Some of the gospel stuff, like “Man Comes Around” — I mean, he would get lost in studying for the song itself, in scripture, and be looking up things in a Thompson chain cross-referencing system for weeks at a time. It almost became an educational thing for him. He was becoming educated through the process of writing. But he never was the kind of person that said, “Oh, it’s time to go to work. I better write a song.” It was never him.

Ferguson: You know, “The Man Comes Around,” I was around for all of that. He worked on that song a long time. He worked on it a long time. He worked on it a long time and it was like, I think that song’s a masterpiece. I think it’s a masterpiece, that song. He’s written some songs that were just glorious, I think, like that song “Redemption,” I think that’s the name of it. “From his hands, it came down / From the side, it came down / From the feet, it came down, ran to the ground.” That’s just incredible writing.

But he also loved great songs and he knew what fit his voice. He wasn’t above recording somebody else’s song, and he was always open to the idea if you would bring him a song. I took him a lot. I took him a Stephen Foster song, “Hard Times Come Again No More.” He goes, “I can’t believe I’ve never heard this song before. And I was like, how did you not know that? Anyway, he loved for people to bring him a song, or a song idea. I think his son-in-law, Jimmy Tittle, took him that song “Unchained” (by Jude Johnstone). Him packing a record with only his songs, I don’t know that he ever did that, other than this one. I don’t know there’s ever been a Johnny Cash record where there wasn’t anything but Johnny Cash songs on it. And I think that’s the point with this one.

Cash: He was a poet. He couldn’t help but write. But when it came time for feeling life, whether it was for healing or whether it was just to get his angst out, or whether if it was to tell a story, he could also look at someone else’s song and know if that could apply to that character that was that songwriter. Like “Hurt” (his hit Nine Inch Nails cover) — I mean, it’s autobiographical, coming from Johnny Cash, because it’s honest. It could just as easily be his words, the same as a great actor or the same as a great writer. And (Depeche Mode’s) “Personal Jesus,” it was not intended to be the message that my dad related when he sang it. But he made it his own, because specifically it was about Christ. It wasn’t originally written as that.

Bob Dylan says he’s one of America’s greatest writers. And I mean, talking about “Big River,” it’s just a wondrous song. But it’s like, on this album, “Well, All Right” is not one of my favorite songs, but people love it. “Hello Out There” [which opens the album] is one of my favorite songs he ever wrote.

“Well, All Right” is valuable on the album as a reminder that your dad loved goofier songs, too, and was not just the Man in Black.

Cash: I mean, case in point, this “The Chicken in Black” business. It’s all over the internet right now. And you know, Dad didn’t like that song…

Wait, “The Chicken in Black” is big now?

Cash: Yeah. It was a big TikTok thing. The song talks about the guy grabbing a chicken and holding it up like a gun and saying, “Get down, everybody, get out of this place. Put all your money in my guitar case.” So what people started doing is grabbing their pets and aiming them at the camera and singing along with my father, lip-syncing to my dad’s track. And so it was this monstrous TikTok thing. And it’s okay. The record sales for that song was went through the roof. He didn’t write it, but he appreciated the song. It was written well, but now it’s just a monstrous hit, you know? It’s what fits and what connects with the people. And who am I to say?

Is there more where this new album came from?

Cash: No, not where this came from. If there’s more, it’s mostly in the American Recordings years. And it’s stuff that maybe my father was more the producer on, because Dad would call different bands in and have different ideas and go into recordings that maybe didn’t necessarily fit within the Rick Rubin releases. And I believe that there are recordings that he would’ve loved people to hear that were done during that time period, but I’m not working on those.

Although most of the backing tracks were replaced on this album, you kept Waylon Jennings in the mix, when he showed up.

Cash: They were really dear friends and, at the time, they were very close, in the Highwaymen years, and Waylon’s office was right across the street. My guess is he just dropped by and Dad said, “Why don’t you sing on a couple?” Or Waylon might’ve said, “I hear a part on there, Johnny.” You know, Waylon did a lot of recording. And I know Shooter just came across some tapes that he didn’t realize how much there was. The way that Shooter’s talking, it’s like there are dozens of Waylon records — like, full albums. Anyway, I’ll let Shooter tell.

Recording in the cabin, even though the original session wasn’t done there, is there still something special about going to that environment for you with your players?

Cash: Man, it’s the only place I ever make music. I mean, this is home. And it’s just where I go for music, no matter what kind of music it is. I spent a lot of life in these walls. But Dad’s definitely a part of this. His energy and spirit is thick in here, you know. It always is. You can feel him around. Of course, he’s definitely in our face for this one with all the working on his voice, working on the tracks, listening to the music. It was great to be in the studio with my dad again, in that way.

Did you get emotional or were you stoic when you were working on?

It was definitely emotional at times. I’d get working on it on a technical level, and then it would just hit me that, you know, wow, I’m back sort of feeling the connection with my father in a way that I didn’t anticipate. One thing is, it connected me back to when he was so strong, and that was a good experience because I’d worked with him a lot in the studio, but mostly when he was struggling, when he was weak. The endurance and the strength that he had through it all, I admire it amazingly. But just to look at the face of the simple thing that he was so strong while he was making these recordings was great.

Best of Variety

Sign up for Variety’s Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.