The Many Lives of Rubén Blades: From Salsa Legend to ‘Fear the Walking Dead’s’ Ruthless Zombie Killer

In his brownstone in Manhattan’s Chelsea district, Rubén Blades is wrapping up a call with a business associate when one last question comes to mind: “Hey, when you seeing Bad Bunny?”

The friend doesn’t know.

More from Rolling Stone

Boza Talks About Finding New Maturity - And Romance - on His Album 'Sin Sol'

'All the Instruments in the World': Jorge Drexler on His Bountiful New Album 'Tinta y Tiempo'

“Just tell him that I would like for him to help me in a production of something I’m doing,” Blades asserts. “See what he says. And let me know.”

Despite their four-decade-plus age difference, the request isn’t surprising. Blades has met Bad Bunny a few times, starting with the time a young Benito and his parents attended a Blades concert in Puerto Rico, and they’ve had at least one phone conversation in which Blades advised him to save his money. Early on, Blades realized the potential of Bad Bunny. “Even that day,” he laughs, “I said to him, ‘I want to do something with you so I can pay my fucking mortgage.’”

With his graying sliver of beard, blue work shirt, and sneakers, Blades resembles a tidier, friendlier version of Daniel Salazar, the Salvadoran death-squad killer turned barber turned zombie killer he’s played in Fear the Walking Dead for eight seasons. As he fends off death and betrayal in the apocalypse, Salazar would surely covet Blades’ home, a converted convent — complete with an elevator and roof deck — that he shares with his wife, the musician, singer, and actress Luba Mason (most recently in Girl From the North Country, the Broadway musical based on Dylan songs).

Blades knows that the general public likely knows him best as Salazar, but those in the music community, especially the Latin one, know differently. Thanks to the likes of Bad Bunny and Rosalía, Spanish-language music has never been more massive nor more uncompromising, pulling in record sales and arena crowds without making blatant crossover moves like English-language records. Starting almost 50 years ago, Blades, who grew up in Panama, helped lay the groundwork. One of salsa’s most charismatic performers of the Seventies and beyond, he made million-selling albums with bandleader and trombonist Willie Colón that validated the breadth and power of the Latin-music market. He also pushed the genre out of his comfort zone, singing and writing songs about street hustlers, people who vanished under Argentina’s military takeover, and superpowers who intervene in Central America.

“He’s always been unapologetic,” says Marc Anthony, who met Blades at the dawn of his own career and became a protégé. “He didn’t give a shit about anybody’s opinion. He was like, ‘Hey, this is me. If you don’t like it, then don’t buy it and don’t consume it. It’s not for everybody.’ He was powerful that way.”

The next generation of Latin artists also seems keenly aware of Blades‘ status. “He’s like a father to my music,” says Puerto Rican rapper Residente. “We didn’t have money to have someone clean the house, so we had to do it for my mom when she went to work. So we’d be listening to his music all the time every morning, blasting albums like Buscando America while we were cleaning. He was teaching me a lot of lessons through his albums.” Residente particularly points to Blades’ “Pedro Navaja,” the tale of the life and death of a criminal, for inspiring him. “It was well-written,” he says. “It was entertaining. It was very cinematographic. And that’s what I do. And I do it because I grew up with his music.”

Yet for all his acclaim, awards, and affability, Blades, who turns 75 next month, seemingly hasn’t lost the burning intensity of his work and persona. His liberal political beliefs are intact, he still gets riled up when talking about the fate of democracy here and in his native Panama, and he’s still writing songs that will make some people squirm, including a new one in the works about child sexual abuse. “Most of the sexual abuse against children comes from family members or people who are known in the family: uncles, grandparents, fathers, friends, close friends,” he says. “No one talks about that. It’s a horrible thing. What about the people who get affected? They deserve to know they’re not alone. But you don’t touch that because again, when you touch it, then the radio doesn’t want to play it.

“People say, ‘Why do you keep singing these songs?’” Blades continues, leaning forward on his couch for emphasis. “Because the fucking problem keeps happening. You think that we cannot have another dictatorship? You think we can’t have another fucking war? You’re wrong.” He punches his fist in the air. “You have to keep fighting.”

THE NEXT DAY, Blades takes in a few exhibits at the Museum of the City of New York. In a section devoted to the city’s cultural history, he sees a flier for an early Grandmaster Flash gig, at a venue where Blades himself played. He stops and smiles at a photo of the Ramones, whom he caught at CBGB. At an exhibit focusing on the history of social and political activism in the city, he nods approvingly. “This is really important that they have this,” he says both approvingly and sternly. “People have no idea what’s going on or what happened before. None.”

Blades’ own New York story dates back to those days and earlier. Born in Panama to a Colombian father (a musician turned member of the secret police) and a Cuban mother (an actress and musician), Blades came to Manhattan in 1969; worried he would get into some sort of trouble at home, his mother bought him a ticket to visit the city, where his brother was working for an airline company, and encouraged Blades to pursue the music career he’d started in his home country. Thanks to a contact he’d made back home, he made his first album during the trip. Back in Panama, he earned a law degree but returned to New York in 1974, where he worked in the mailroom of the leading salsa label, Fania. First joining Ray Barretto and the Fania All-Stars and then, in 1977, Colón’s band, Blades quickly became one of salsa’s young guns, its newest soneros.

The combination of Colón’s expertise and Blades’ singing, stage presence, and topical lyrics took salsa to levels few had seen before. On albums like 1978’s Siembra and the double-disc Maestra Vida, Blades wrote about the downside of Western-culture assimilation (“Plastico”) and the travails of the working class (“Pablo Pueblo”). According to Blades, Fania was less than enthusiastic at first. “They were not happy with the material,” he says. “But they let me do it only because Willie was involved. Willie must have said, ‘Hey, it’s going to be good, it’s going to be OK.’” Siembra would become the bestselling salsa album of its time, reportedly selling several million copies.

“In the neighborhood, and in my house, it was what you would liken to a Number One pop record that’s playing everywhere,” Anthony says of Siembra. “You were constantly aware of it.“

When Anthony was launching his own career around that time, he and Blades shared the same manager, who suggested Anthony work as Blades’ tour assistant to learn more about the business. On a tour with his hero, Anthony was given a job as what he describes as “towel boy and water boy” for Blades. “I would stand on the side of the stage and just marvel,” he says. “I would be just dying for him to ask for a towel, dying for him to get thirsty so I could run up onstage. I never met anyone like that. He would read The New York Times on the bus.”

Leaving Colón’s band, Blades formed his own, Seis Del Solar, and signed with Elektra, becoming the only Latin act on a label dominated by the likes of the Cars, Queen, and Jackson Browne. His first album for the label, 1984’s Buscando America, was both lyrically ambitious and musically grounded to his roots. “El Padre Antonio y el Monaguillo Andrés,” about the murder of a priest and an altar boy, made a particularly strong impression on Lin-Manuel Miranda, whose parents had Blades’ albums in their record collection. The song, Miranda says, proved “you can write a tasty hook, you can write incredibly complex rhythms, and you can be telling a story all at the same time. I really don’t know of any other Latin writers who staked out so much territory for what can be a song. It’s like if you listen to pop music on the radio your whole life, and then you hear Randy Newman and go, ‘Oh, my God, it can also be that.’”

Just before Buscando America was released, Blades previewed the album for Elektra staff in a conference room, acting out the parts and explaining the songs in English. “It was so moving, and we thought, ‘This is incredible,’” says Sari Becker, the label’s publicist at the time. But since the music business at the time tended to marginalize the Latin market, Becker says not everyone in the company knew what to do with it. “The sales department was really angry at us for spending so much time with Rubén and the album,” she says. “It wasn’t something they could get on the radio.”

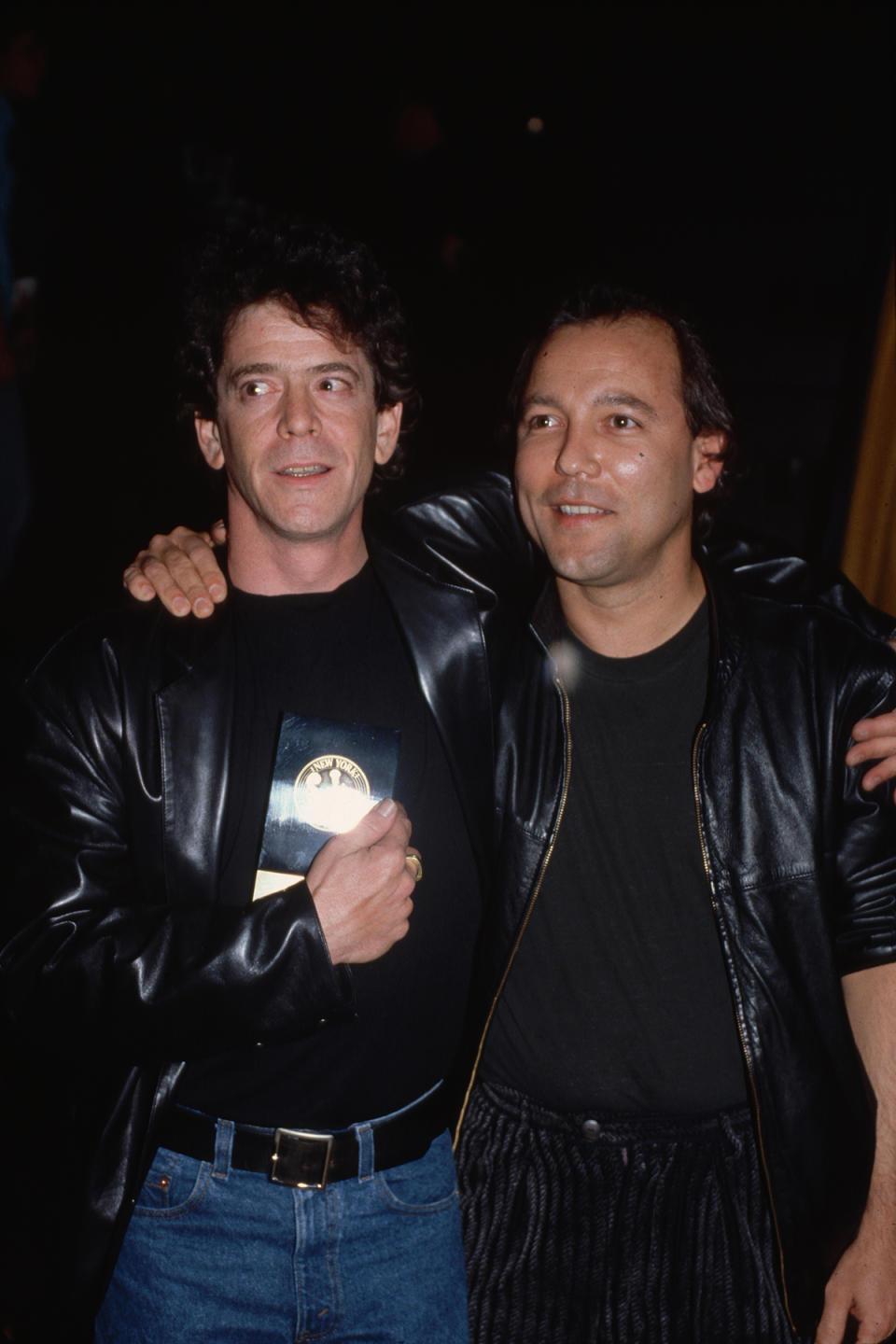

Nonetheless, Blades used his major-label moment in the Eighties to push several envelopes. On 1985’s Escenas, he showed how synthesizers could be as much a part of his genre as horn sections. Agua de Luna was based on the short stories of Gabriel García Márquez, and he talked Elektra into letting him make an English-language rock album, Nothing But the Truth, with songs co-written with Lou Reed, Paul Simon, and Elvis Costello. For that project, Blades also hooked up with Bob Dylan to write a song Blades says would have been about “people who want things they don’t need who ended up doing things they shouldn’t be doing.” Since Blades didn’t (and still doesn’t) have a driver’s license, Dylan had to visit him at the apartment Blades was renting and kidded Blades about it. Unfortunately, the song was never completed.

Blades wouldn’t be constrained in other ways. He made his acting debut during his time with Colón, playing a boxer in the low-budget The Last Fight. But starting in the Eighties, he ventured even deeper into that world and wound up with roles in feature films that starred Robert Redford, Harrison Ford, Whoopi Goldberg, and others. In 1990, he almost lost out on a role in Roman Polanski’s The Two Jakes thanks to a tour he had scheduled, but a call from star Jack Nicholson changed his mind. Nicholson invited Blades over to his house in L.A., greeted him outside in a Japanese bathrobe, and told him he was a fan of Blades’ music. “You think I’m bullshitting?” he said, revealing his collection of Blades albums. He then arranged so that Blades could still play one of his shows, fly to the movie set the next day, and return in time for the next gig.

By straddling music, Hollywood (where he lived for a time in the Nineties), politics, and celebrity, Blades risked wrecking his credibility. But in light of the ground he was breaking as a Latino musician and actor, few held his crossover moves against him. “You can get down with Rubén Blades at any level,” says Miranda. “You can be a fan of Predator 2 and still connect with Rubén. You can want to dive deep into Latin American history and find that in his music as well. It’s whatever entry point you want.”

BLADES’ OUTSPOKENNESS BOLSTERED him as well. In 1980, Blades and Colón were booked to play Studio 54, the New York disco still in its heyday. Blades was told not to say anything political onstage and to wear a suit and tie. Just before their set, a DJ-MC announced to the largely Latino crowd, “Another door opened for our music — we finally made it!”

Despite his marching orders, Blades — who showed up in a T-shirt with suspenders, jeans, and “the oldest hat I had” — couldn’t help himself. “This event is billed as a giant step for Latinos — that’s bullshit!” he told the stunned crowd. “If you want to make giant steps for Latinos, you should all register and vote!” Backstage between sets, an argument between him and the promoters ensued. “I said, ‘You’re just so stupid,”’ he recalls. “’We have a fucking heroin epidemic in this city, and you’re talking that we arrived? The fucking Bronx is, like, burning.’” To him, the club was only allowing Latinos in “to make money,” he said later. He finished the show, but at time, the MC was none too happy, telling the newspaper Latin New York, “It wasn’t so much his speech that bothered me, it was his portrayal of the facts in such an unethical, impolite, and unintelligent way.”

Looking back on that moment now, Blades pauses for a moment. “I hope I didn’t offend some people,” he says, finally. “But I wouldn’t take it back.”

Neither, he says, does he have regrets about songs that were at various times banned in Miami, Cuba, and even his home country, resulting in a degree of backlash. “Some people say, ‘You’re a hypocrite because you criticize the U.S. and you live there,’” he says. “And I said, ‘Look, go to the fucking dictionary and look up the word hypocrite.’ Hypocrite is the person who doesn’t say what they feel. When Reagan was in power, and they’re intervening in Central America, I’m writing about that. I don’t have a problem with the United States. I don’t have a problem with the New York Yankees. I don’t have a problem with my wife’s family. I’m making a statement about something that I feel very strongly is wrong.”

His voice rises. “I wasn’t asked like, ‘OK, you get your green card, but you can’t say shit about this country.’ Because then I would have said, ‘Sorry, I thought this was the United States. This is not China or some fucking communist country.’”

Blades also made waves, and a few enemies, fighting for his and others’ rights. In 1984, he sued Fania, claiming he hadn’t been paid for publishing and record royalties. The suit was settled out of court, but Blades wound up suing the company again, in 2004, claiming the deal had been breached. Speaking more broadly about the music business, he adds, “They used to call it ‘paying your dues.’ That’s not paying dues. That’s abuse. No, you’re not gonna buy me with a little coke or show me a girl. Fuck you. Not gonna happen. You’re gonna fucking pay us.” Soon after, he earned a master’s degree in international law from Harvard, all while promoting Buscando America.

Even when he didn’t intend it, a degree of controversy followed him. In 1997, he took a co-starring role in The Capeman, the Paul Simon-written Broadway show based on the true story of Salvador Agron, a 16-year-old Puerto Rican in New York who stabbed two teenagers, thinking they were gang members. Anthony played the younger Agron, Blades the older, imprisoned one. A teenage Miranda saw the show three times, once waiting by the stage door so that Blades could autograph his copy of Maestra Vida. But on opening night, family members of the victims protested: “Other people’s tragedy is not entertainment,” said one. Already battered with mixed to poor reviews, the show — now considered ahead of its time — closed just under two months later.

The protests still rankle Blades. “Let me tell you about that, how wrong that was,” he says. “We’re doing previews. Then we’re having people — I never knew how many — attacking Paul and saying The Capeman glorifies murders. I say, ‘Have they ever heard of a play by Sondheim called Assassins?’ Were there any pickets for that one? Another one: Ragtime. You got a guy who’s blowing up people’s property because he’s pissed. Isn’t that terrorism? It was so unfair. Paul was not treated right. I was very surprised by that. And if I had thought it was a glorification of murder, I would have not played the character.”

Anthony recalls Blades helping to keep everyone’s spirits up backstage. “Shit, I cried half the time — it was so brutal,” he says of the experience during the show. “But Rubén was always the one who would fortify everybody, saying, ‘What we’re doing is brave. We’re still showing up. There’s no way I’m ashamed of this being on my résumé — if anything, it’s one of the proudest projects I’ve ever been a part of.’”

On the upside, The Capeman is where Blades met fellow cast member Mason, who only knew Blades for his film roles. “I’m in rehearsal and I start hearing this guy singing, and I said, ‘He sounds pretty good for an actor,’” she says. “It was an all-Latin cast, for the most part, and they’re looking at me like, ‘You don’t know who Rubén Blades is?’” The two married in 2006.

RECENTLY, MIRANDA WAS in New York’s theater district when he ran into a familiar face: Blades. “He’s like, ‘Lin-Manuel, you have to buy a theater — the same three guys own all the theaters,’” Miranda says. “I said, ‘I don’t want to run a theater!’ He says, ‘No, Lin-Manuel. It’s your responsibility. You gotta buy a theater so we can put up our shit.’”

Miranda was neither the first nor likely the last Latin artist who would hear from Blades. He’s now an elder statesman, keeping an eye on rising talent and advising them on ways to avoid the pitfalls he’s experienced, financially or otherwise. Residente has known Blades for about 15 years, dating back to his days with his alt-reggaeton band Calle 13. “He gives me advice every moment I ask, and sometimes I don’t ask and he still sends me a message,” he says. “Every time I fucked up by saying something that maybe I should have said a different way, he sends me an email. Not in a bad way, but just giving me advice. Through my whole career, he’s been that person.”

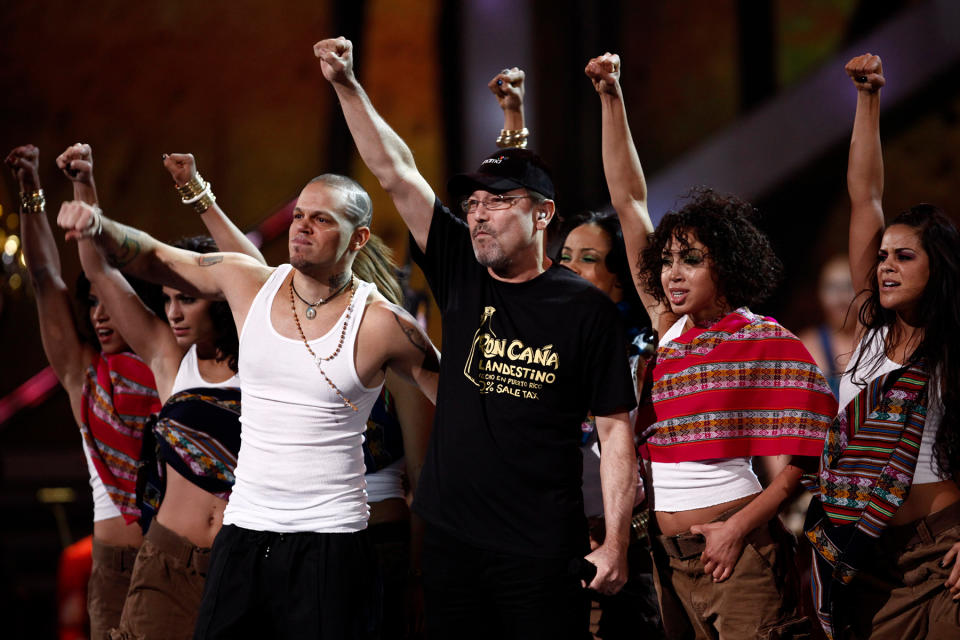

Last year, Blades took an even-more proactive stance when a feud broke out between Residente and J Balvin. After Balvin proposed a boycott of the Latin Grammys, claiming the awards didn’t give enough props to reggaeton, Residente took offense and went after Balvin in an eight-minute freestyle track. Blades was drawn into the throwdown when Residente also thought Balvin’s idea for a boycott was unfair to Blades, who was receiving a Person of the Year honor. “I found it disrespectful to Rubén — anyone who calls for people not to go to the Grammys where this guy who is a master and a mentor [is being honored].”

To take the war down a notch, Blades stepped in with a video of his own, in which he called on Residente to chill. “It was beginning to get nasty,” says Blades. “I thought, ‘No, not the time to have this fire spread. Let’s cut this shit. Now.’ I thought it might lead to escalation. Look what happens between Biggie and Tupac.”

Residente says he took it in stride and remains on close terms with Blades. “He just told me, ‘Look, I did this in a fun way, but also saying what I think,’” Residente recalls. “And I said, ‘Yeah, man, that’s fine.’”

“This I tell everybody,” Blades says. “What the fuck good is knowledge if you don’t share it? So if I can have something that’s going to help them not make the mistakes I’ve made, and have them do something better? I’m not saying I’m perfect, because I’m not. But it’s a contribution.”

Indeed, thanks to his own screwups, Blades insists he shouldn’t be called, in his words, “St. Rubén.” He still regrets using a racial epithet to describe the audience during the Studio 54 incident. A few years ago, he learned he had a son from a previous relationship. He declines to go into specifics, but says he was dismissive of the claim when it was brought to his attention and only realized he was wrong after taking a paternity test. “That’s something I will never fucking live down, ever,” he says solemnly. “That’s my worst moment in my whole existence. I have a great relationship with my son. Fucking sent me a Father’s Day card. And I said, ‘I’m like the last fucking guy you should send a card to.’ He said, ‘Let’s see towards the future,’ and I said, ‘That’s very big of you.’ But I will never stop looking back at this. I always try to do things right. And I fucked up this one.”

AS BLADES MAKES his way through the museum exhibit, the topic of the Latino vote, in last year’s midterms and the upcoming 2024 presidential election, comes up. Blades has seen the polls and stats in which Latino voters have been veering more right, and he doesn’t disagree. “You have to consider the fact that Latinos are conservative, most of us,” he says. “So issues like abortion, the right to life, are very large in the way we were all brought up. Also, few people leave a country because they want to. We are driven out, by some reason, whether it is a dictatorship or lack of opportunity or gangs. So when we come to a country that accepts us, we feel it’s almost a betrayal to criticize. So rather than becoming involved in politics, a lot of people say, ‘You know what? I don’t want to make waves. I’m grateful. So I’m not gonna get involved.’”

He also points to the impact of crime and law and order. “People are immediately impressed with anybody who says, ‘I want to stop crime. I want to bring order to things,'” he says. “So it’s all those things combined. And the Democrats have been horrible in explaining that they can, in fact, empathize and guarantee the same concerns. The Latino shift should be of concern for the Democrats. The message is not getting there. And the image they’re projecting doesn’t instill trust in Latino voting blocks.”

Taking a seat in a museum coffeeshop, where two older Latino customers recognize him and ask for a selfie, he continues. “Young kids, they say, ‘Politics is shit,’” he says. “I say, ‘Yes, because you let shit people get in politics. Why don’t you want to get in? Somebody’s got to drive the bus.’”

At least once, Blades tried to set an example. By 1993, he’d been talking about returning to Panama for a possible presidential run. In 1994, he delivered on that promise, offering himself as a solution to dictators and corruption. “I always knew he would run for president,” says Anthony. “I mean, if you didn’t see that coming …”

After placing third, Blades returned to music and acting, but in 2004, after the election of Martin Torrijos, he took a job as the minister of tourism in Panama. Blades came in with criticism (“Successful artist; unpopular minister,” read one newspaper headline), but he also scored his share of accomplishments, like recruiting gang members as tour guides. “We ran a [training] program to make sure you don’t have a fucking psychopath saying, ‘Let me show you something,’” he recalls with a laugh. But more seriously, it seemed to work: The original lineup of 60 gang members was whittled down when seven died and others quit the program, but in the end, Blades says, 25 wound up working those jobs.

When his term in office expired in 2009, Blades found himself without his old career and little income. He applied for a loan to purchase the brownstone he would eventually buy in 2015 and was turned down since he hadn’t made enough money in the ministry of tourism job, which paid $65,000 a year. “We went to have a coffee, and he wanted to see the state of things,” says Anthony, who by then was a major star in his own right. “He wanted to know what booking was like now. What concerts were like. The industry had changed. He was curious. I don’t know if Rubén ever worries. He just sees change as a challenge.”

Blades put together his old band and hit the road, opening for Anthony. One sign that his core audience hadn’t forgotten him came at Miranda’s wedding, to Vanessa Nadal, in 2010. During the reception, Blades, an invited guest, joined the wedding band to sing “Pedro Navaja.” “This was a Puerto Rican and Dominican wedding,” Miranda says. “You imagine the collective loss of minds that happened when Rubén jumped up onstage and started singing that song.”

Around that time, Dave Erickson, the co-creator of Fear the Walking Dead, approached Blades about the role of Salazar, who is essentially the anti-Blades — “a killer, worked with the right wing, the antithesis of what I am politically.” But beyond the acting stretch, the job appealed to him on multiple levels. “People were asking the internet, ‘Is he dead?’” he says. “So that was also the reason. It helped me get back on the saddle and not have all my eggs in one basket. It provided me with a steady income but also visibility, which is super important in this business.” (Complaints about the shows’ recent seasons also rile him up: “I see people go, ‘What went wrong with Fear the Walking Dead?’ We had more seasons than Breaking Bad or Better Call Saul. What are you talking about, ‘What went wrong?’”)

Since he’ll be 80 in five years’ time, Blades has gone into creative overdrive, especially now that Fear the Walking Dead has finished filming for good; the first half of its last season just aired, with the second half coming this fall. (He’s mum on the fate of his character, who has already survived being shot in the face, a possible drowning, and being struck by lightning: “Let’s say that Daniel fans are going to be happy, OK?”) He’s working on a memoir, which also serves as a reminder to him of how few volumes have been written on Latin music. “Show me how many books are there on Elvis Presley,” he says. “Then show me how many books are there on Willie Colón or Ray Barretto or Machito or Héctor Lavoe or Celia Cruz. Why we don’t write about our own people, I don’t know. That is so fucking weird. It’s like we don’t care.” He also has several albums in the works: a big-band-rooted duet album with Mason (a thematic work tracing the saga of a relationship); a new, track-by-track live recording of Siembra to celebrate its 45th anniversary; another record steeped in Brazilian music; and another big-band album along the lines of 2021’s Salswing! He and Residente are also collaborating on a new track that brings back several characters in classic Blades songs, like Pedro Navaja, and connects their lives.

Blades recently auditioned for, but didn’t land a part in, a Marvel movie. That sounds surprising — at least until Blades takes the elevator to the fourth floor of his building, which is crammed with his collection of roughly 10,000 comic books, from pristine first issues of Batman and Superman up through X-Men and even Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles collections. “When I’m on the first floor, I’m 74,” he says, “but by the time I walk up here, I’m 15 again.” It’s also where he stashes his 11 Grammys, including the one he won this year in the Best Latin Pop category for Pasieros, a collaboration with the Brazilian band Boca Livre.

Blades has ruled out running for further political office. But disgusted by the state of politics in his native Panama (he remains a citizen of that country, with a green card here) and dreading the possible return to power of former President Ricardo Martinelli, Blades is also working on a campaign to encourage more than 300,000 young voters in the country to vote for other candidates. He’s equally concerned about this country. “I hope Trump doesn’t fucking win again,” he says. “I told [Mason], ‘If he wins, I’m fucking out of here. Swear to God.’ I cannot see this country destroyed by somebody like that. Biden perhaps is not the best guy because of his age. But he’s the perfect guy for setting the tone. The status quo has to be changed, but he can guarantee it won’t happen in a violent way. Trump is a fucking sociopath.”

As far salsa, Blades remains optimistic about its future even with other Latin genres taking center stage these days. “It’s not like reggaeton just came out,” he says. “It’s been around for 15, 20 years. That’s what’s occupying everybody’s attention right now. But salsa is a world movement. It is played right now in Pakistan. There’s a salsa band in Israel. It is true that salsa clubs have disappeared, but the music is not going to disappear and the clubs will come back. It’s like a pendulum.”

Back in his home, he stands up to demonstrate. “I’m going to the club. I want to dance with a girl — or a boy, or whatever you’re going to do. They put on the music.” As if he were a dancing instructor, he pantomimes approaching and clasping hands with an invisible partner, moving to unheard music. “It’s a Black person with a white person, an Asian person with a Latin person. The two of them are touching.” He presses in closer to his invisible partner. “You both have to be together.”

Then he sits back down. “Everybody’s in their own fucking bubble, on the phone,” he says. “Nobody wants to get involved with nobody. I see that more and more. But with salsa, no. People need to have people around them.” And then he gets up and takes one more dance.

Best of Rolling Stone