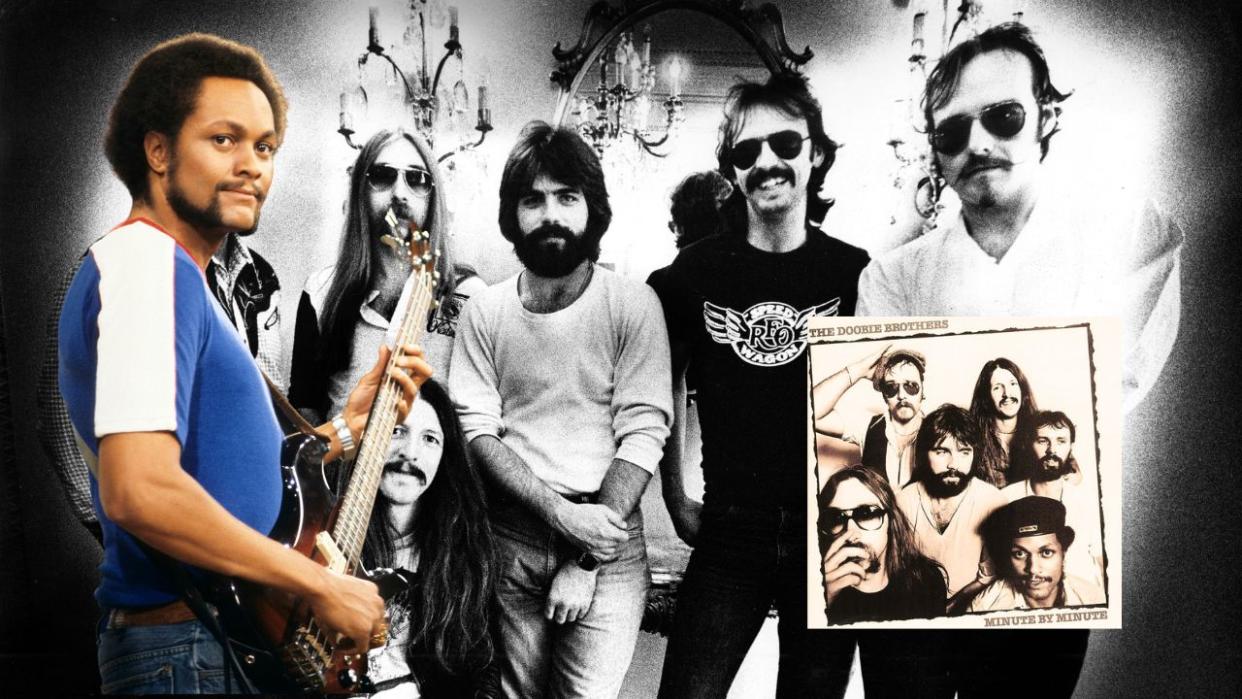

“When Michael McDonald first played it for me, I had him slow down and just show me his left hand”: Tiran Porter on The Doobie Brothers’ Minute By Minute

Tiran Porter was a member of The Doobie Brothers for the band’s busiest years, but 1978 may have been the busiest of them all. “We were constantly on and off the road,” Porter told BP. “That’s why it took a year to make Minute By Minute.”

Two singles from the album, both co-written by Michael McDonald and released in 1979, went on to score big at the 1980 Grammy Awards. What a Fool Believes was named Song of the Year and Record of the Year, but it’s follow-up single, the album's title track Minute By Minute, was also nominated for Song of the Year, and won Best Pop Vocal Performance by a Duo or Group.

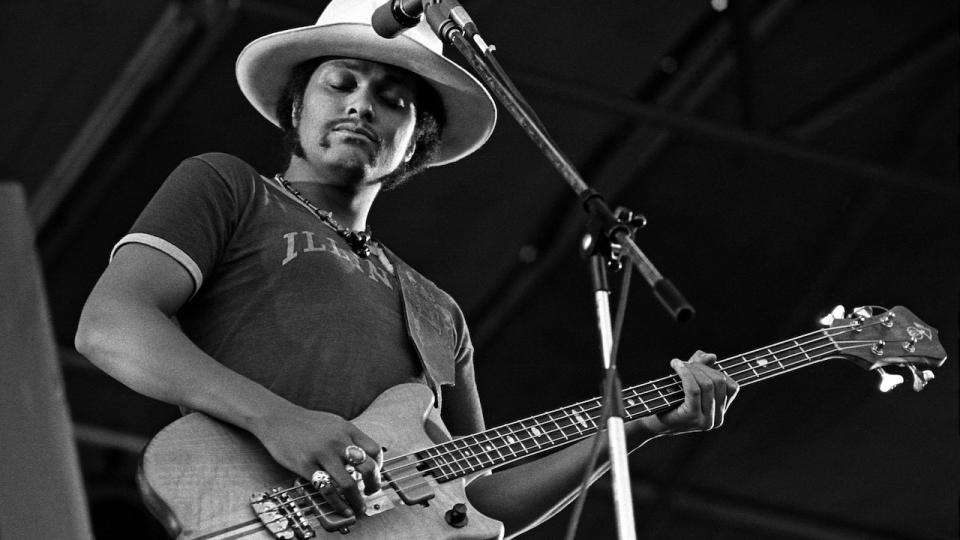

Speaking to BP in 2014, Porter said that while the What a Fool Believes bassline was written almost entirely by McDonald, Minute By Minute was developed more collaboratively, with McDonald sketching out what Porter calls the verse’s “cowboy-movie-theme-meets shuffle-feel” bassline. “When Michael first played that for me, I couldn’t hear what he was doing. I had him slow down and just show me his left-hand.”

The track’s tricky opener starts with a mid-fingerboard D, with Porter following McDonald’s left-hand keyboard octaves. By the end of the third time through, drummer Keith Knudsen enters, establishing the 4/4 shuffle groove. The transition between the two different feels is fairly abrupt, and it’s even more jarring when it happens again at the bridge.

The verse vamp enters with the simple 1-5-6-5 “cowboy” bassline, but the way it aligns with McDonald’s right hand chord rhythm is noteworthy. Viewed from a thousand feet, the whole verse section is Cmaj7, but break out the magnifying glass and you’ll see that the keyboard cycles through Em7, Dm7, and Cmaj7, each played for a quarter-note, for two three-chord cycles in each 12/8 bar.

That gives the groove a three-against-two polyrhythmic feel, with the offset rhythms of the shuffling bass and triplet keyboard stabs converging twice in each bar, where the Cmaj7 chords hit on beats one and three.

As for the in-between chords, the Em7 aligns with its chord tone G in the bass, and the Dm7 comes just after its chord tone A. Note that the last two notes of the scale-like fills in the vamps second and fourth bars mirror each other.

“That was planned. I’m all for spontaneity and jamming, but there’s something to be said for composition,” said Porter. “I didn’t get too much chance with this, though. I wasn’t able to overdub or tailor my part to the vocals.”

A G major scaler lick leads into the chorus, which resumes the shuffle rhythm. At the end of the chorus, Porter revisits his scaler verse-vamp fill before diving into the second verse. After a few choice variations from the first time through, it’s back to the main vamp and the three quarter-note hits just before the bridge.

The same climbing eighth-note octaves from the intro return, but this time the drums hold onto the 12/8 rhythm. After two rounds through the full band play the unison E-D-B lick leading to the bridge and key change to E minor, before finally leading to the cathartic outro chorus, now in the key of G.

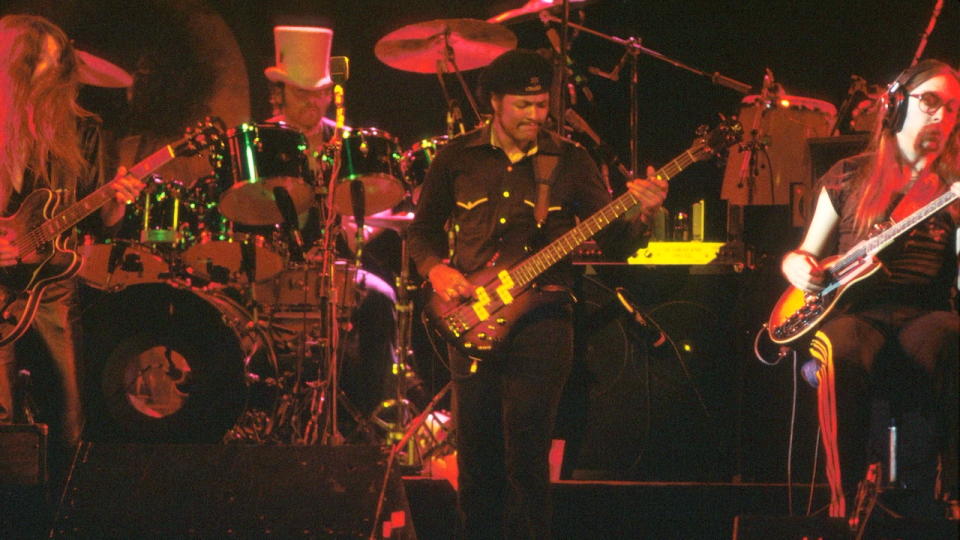

Present for the session were McDonald, Porter, percussionist Bobby LaKind, and drummer Keith Knudsen. Guitars and vocals came later; in fact, the melody and lyric hadn’t really been worked out at the time the basics were cut. “It was a complete head arrangement,” lauded Porter. “There weren’t even chord charts.”

Porter used different basses each year with the Doobies. In 1978, it was a B.C. Rich Mockingbird with twin DiMarzio P-style pickups. Porter played fingerstyle, as opposed to the Precision and Alembic he picked on earlier tracks.

At that time the Mockingbird was a radical new design, with dramatic curves and points (“I didn’t care what it looked like. It sounded great”). The bass went direct into the board alongside a track of mic'd Ampeg B-15, the same bass guitar setup on all the Doobie Brothers recordings.

Porter left the Doobies in 1980 when the road schedule got to be too much, both personally and professionally. With the group constantly performing, songs were written in the studio or on the road, with no time to sit with the tracks, which wasn’t Porter’s preferred way of working. “I feel a lot better about my parts when I can live with them. I like to make sure what I’m doing fits with everybody.”