Michelle Obama: It's Up to Us as Mothers to Give Girls the Support That Keeps Their Flame Lit

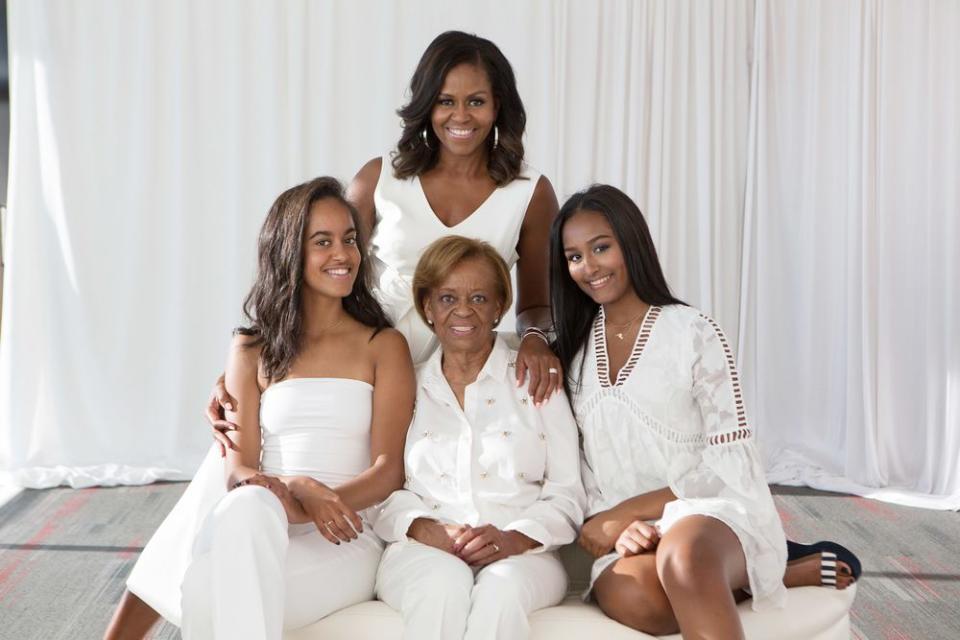

In honor of Mother’s Day this year, Michelle Obama shares memories of her mom, Marian Robinson, and women who shaped the extraordinary life of the girl from Chicago’s South Side who would grow up to be America’s first lady. In a special personal essay, excerpted here, for the new issue of PEOPLE, Obama reflects on what she learned about parenting from her own mother:

My mother is a woman who chooses her words carefully. She’ll sometimes speak in clipped sentences, her wisdom packed into short bursts and punctuated with an infectious smile or a wry laugh. It’s a style that makes her a favorite of everyone she meets — a sweet, witty companion who doesn’t need the limelight.

As I’ve grown older, I’ve seen how her manner in conversation also reflects her approach to parenting. Because when it came to raising her kids, my mom knew that her voice was less important than allowing me to use my own.

That meant she listened a lot more than she lectured. Growing up, she was willing to endure endless questioning from me — Why did we have to eat eggs for breakfast? Why do people need jobs? Why are the houses bigger in other neighborhoods? She didn’t chide me if I scrapped with some of the neighbor kids or challenged my ornery grandfather when I thought he was being a little too ornery. She listened intently to the lunchtime conversations I had with my schoolmates over bologna sandwiches, and nodded patiently along to tales of my contentious piano lessons with my great aunt Robbie.

In today’s world, it’s easy to hear all that and think that Marian Robinson was bordering on negligent, that she was letting the kids rule the roost. But the reality was far from that. She and my father, Fraser, were wholly invested in their children, pouring a deep and durable foundation of goodness and honesty, of right and wrong, into my brother and me. After that, they simply let us be ourselves.

… I see now how important that kind of freedom is for all children, particularly for girls with flames of their own — flames the world might try to dim. … It’s up to us, as mothers and mother-figures, to give the girls in our lives the kind of support that keeps their flame lit and lifts up their voices — not necessarily with our own words, but by letting them find the words themselves.

For Mrs. Obama’s complete personal essay on motherhood, pick up the new issue of PEOPLE on newsstands Friday.

Below is an excerpt from Michelle Obama’s bestselling memoir, Becoming, in which she recalls how her great-aunt Robbie’s tough love and piano lessons helped shape who the woman she is today:

At home, I continued to work on my own progress as a musician. Sitting at Robbie’s upright piano, I was quick to pick up the scales — that osmosis thing was real — and I threw myself into filling out the sight, reading worksheets she gave me. Because we didn’t have a piano of our own, I had to do my practicing downstairs on hers, waiting until nobody else was having a lesson, often dragging my mom with me to sit in the upholstered chair and listen to me play. I learned one song in the piano book and then another. I was probably no better than her other students, no less fumbling, but I was driven. To me, there was magic in the learning. I got a buzzy sort of satisfaction from it. For one thing, I’d picked up on the simple, encouraging correlation between how long I practiced and how much I achieved. And I sensed something in Robbie as well — too deeply buried to be an outright pleasure, but still, a pulse of something lighter and happier coming from her when I made it through a song without messing up, when my right hand picked out a melody while my left touched down on a chord. I’d notice it out of the corner of my eye: Robbie’s lips would unpurse themselves just slightly; her tapping finger would pick up a little bounce.

This, it turns out, was our honeymoon phase. It’s possible that we might have continued this way, Robbie and I, had I been less curious and more reverent when it came to her piano method. But the lesson book was thick enough and my progress on the opening few songs slow enough that I got impatient and started peeking ahead—and not just a few pages ahead but deep into the book, checking out the titles of the more advanced songs and beginning, during my practice sessions, to fiddle around with playing them. When I proudly debuted one of my late-in-the-book songs for Robbie, she exploded, slapping down my achievement with a vicious “Good night!” I got chewed out the way I’d heard her chewing out plenty of students before me. All I’d done was try to learn more and faster, but Robbie viewed it as a crime approaching treason. She wasn’t impressed, not even a little bit.

RELATED: Michelle Obama‘s Becoming, with 10 Million Copies Sold, Could Be the Most Popular Memoir Ever, Publisher Says

Nor was I chastened. I was the kind of kid who liked concrete answers to my questions, who liked to reason things out to some logical if exhausting end. I was lawyerly and also veered toward dictatorial, as my brother, who often got ordered out of our shared play area, would attest. When I thought I had a good idea about something, I didn’t like being told no. Which is how my great-aunt and I ended up in each other’s faces, both of us hot and unyielding.

“How could you be mad at me for wanting to learn a new song?”

“You’re not ready for it. That’s not how you learn piano.”

“But I am ready. I just played it.”

“That’s not how it’s done.”

“But why?”

RELATED VIDEO: Michelle Obama Shares the Advice She’d Give Meghan Markle: ‘Don’t Be in a Hurry to Do Anything’

Piano lessons became epic and trying, largely due to my refusal to follow the prescribed method and Robbie’s refusal to see anything good in my freewheeling approach to her songbook. We went back and forth, week after week, as I remember it. I was stubborn and so was she. I had a point of view and she did, too. In between disputes, I continued to play the piano and she continued to listen, offering a stream of corrections. I gave her little credit for my improvement as a player. She gave me little credit for improving. But still, the lessons went on.

Upstairs, my parents and Craig found it all so very funny. They cracked up at the dinner table as I recounted my battles with Robbie, still seething as I ate my spaghetti and meatballs. Craig, for his part, had no issues with Robbie, being a cheerful kid and a by-the-book, marginally invested piano student. My parents expressed no sympathy for my woes and none for Robbie’s, either. In general, they weren’t ones to intervene in matters outside schooling, expecting early on that my brother and I should handle our own business. They seemed to view their job as mostly to listen and bolster us as needed inside the four walls of our home. And where another parent might have scolded a kid for being sassy with an elder as I had been, they also let that be. My mother had lived with Robbie on-and-off since she was about sixteen, following every arcane rule the woman laid down, and it’s possible she was secretly happy to see Robbie’s authority challenged. Looking back on it now, I think my parents appreciated my feistiness and I’m glad for it. It was a flame inside me they wanted to keep lit.