Mick Jagger’s ‘ideal woman’: How Fran?oise Hardy seduced swinging London

The front page splash of Melody Maker on May 22 1965 didn’t hold back. “Jackie leads chicks chart invasion!” it screamed, before explaining how Staffordshire’s Jackie Trent was “thrilled to bits” to be number one that week. The story then named all the other “chicks” riding high in the singles chart: among them, Marianne Faithfull, Sandie Shaw, Cilla Black and Fran?oise Hardy.

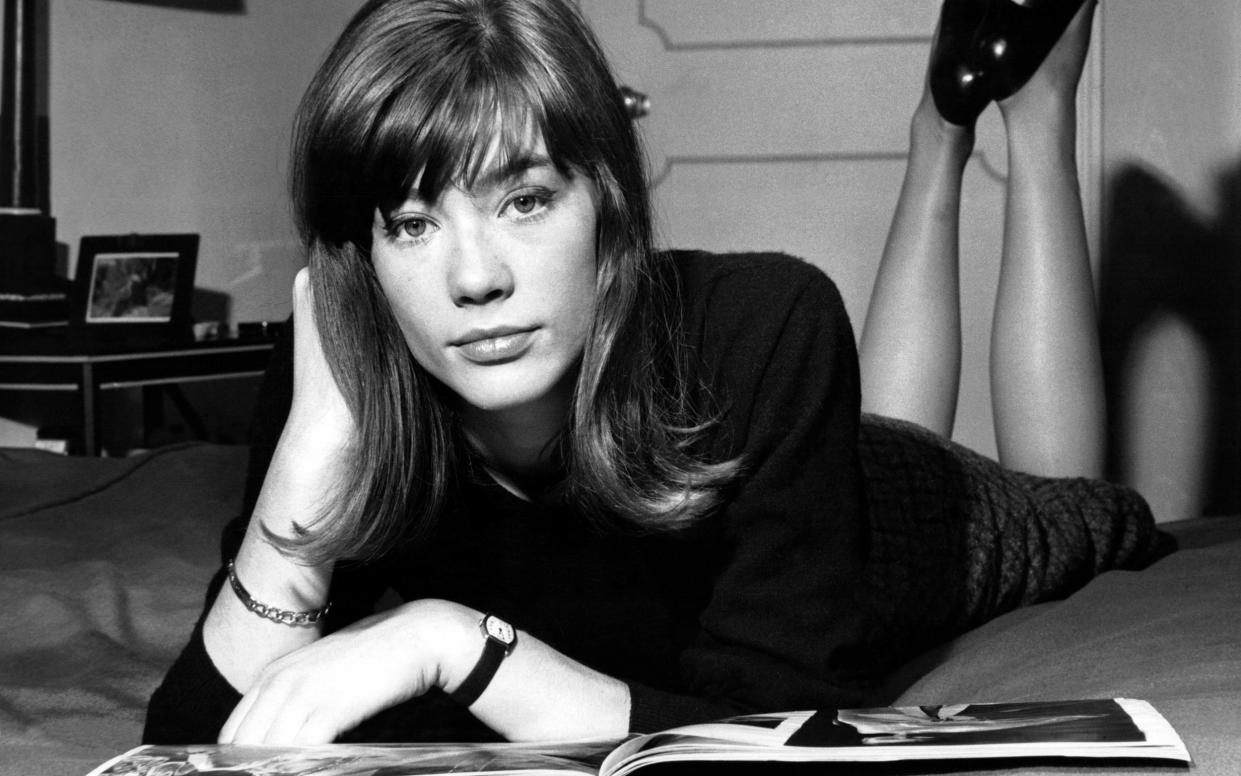

Paris-born Hardy, at number 16 that week with All Over the World, was singled out for special attention. At the bottom of the page, beneath images of Mick Jagger and Bob Dylan, was a photo of the 21 year-old, sultry and unsmiling beneath her trademark fringe. “Fran?oise Hardy – Continental pop invades the chart” read a second headline. That year Melody Maker readers voted Hardy, already a big star in France, their third favourite female singer after Dusty Springfield and Brenda Lee.

Hardy had become a pop phenomenon in the UK. Indeed the singer, who has died aged 80, seduced London and was seduced by it in equal measure. She recorded much of her best work here and filmed pop videos in tourist-y locations: on the London Underground, next to Tower Bridge and even driving around Piccadilly on an open-top bus wearing pyjamas. She’d visit pubs and sip pints of bitter. It was quite the pivot for the poster girl of yé-yé, the jauntily breezy and manufactured French pop style through which she’d made her name back home.

It wasn’t only British pop fans who noticed Hardy. She drew the attention of Jagger and Rolling Stones bandmate Brian Jones. David Bowie admitted to being smitten with her. She had dinner with two Beatles. And tragic folk hero Nick Drake almost recorded with her. Her connections with British musicians didn’t end there. In 1995 when Britpop was at its height, Blur recorded their song To The End with Hardy singing the verses in French. It was released as the B-side to the band’s mockney cor-blimey-me-old-china single Country House – at the time the epitome of Britain’s pop cultural identity.

Explaining her Anglophilia, Hardy said that London liberated her from her fabricated image in France. Fed up with being pigeonholed, she insisted in 1963 on recording in London and linked up with producer Chris Blackwell. “I was happy from that moment,” she said in a 2018 interview. “I was free to make another kind of music, not this mechanical music I had been trapped in.”

You can hear the difference in her output. Her breakout 1962 hit Tous Les Gar?ons et Les Filles, recorded in Paris’s Studio Vogue, was an airy and pretty slice of pop. But her 1964 album Mon Amie La Rose, recorded in London, was a darker and more dramatic beast altogether. It included the song Je N’Attends Plus Personne, on which a filthily scuzzy guitar line was provided by a pre-Led Zeppelin Jimmy Page. Sixty years on it still sounds unhinged, like something metal duo Royal Blood might come up with. Mon Dieu, indeed.

Hardy was in many ways doing a reverse Petula Clark. The Surrey singer had proved to be a big hit in France in the early 1960s. Clark recorded songs by Serge Gainsbourg and Jacques Brel and moved to Paris for seven years. In a strange musical French exchange, Hardy did the precise opposite. “Many felt that Hardy’s career was paralleling that of Britain’s Petula Clark, who had moved to France and become a pop star there,” wrote pop historian Nick Johnstone in 1999.

Given her striking looks, it was not surprising that Hardy attracted the attention of Britain’s pop elite. She took it all in her stride. “I think I was a source of fascination for the English pop musicians,” she said in 2018. Jagger once described her as the “ideal woman”. Jones took to visiting her at her hotel. “I heard much later that there was a rumour that I was a lesbian, but really I was just shy and unsure. When Brian Jones introduced me to his girlfriend, Anita Pallenberg, I was very flattered and charmed, but then I heard that they were each trying to figure out which one of them I was interested in sexually,” Hardy told The Guardian. “Of course, this was the very last thing I was interested in. I was unbelievably innocent.”

Bowie was a huge fan. “I was for a very long time passionately in love with her,” the singer told a French TV interviewer in January 1997. “As I’m sure she’s guessed, every male in the world and a number of females also were. And we all still are.” The appreciation was reciprocated – Hardy was herself a Bowie fan. Displaying admirable Gallic obtuseness, she once revealed her favourite Bowie track to be I’m Deranged from his 1995 album Outside, hardly a fan favourite. She told Bowie as much “and he was stunned. He couldn’t believe it. I think he was quite happy to hear that”.

But it was perhaps Nick Drake with whom Hardy had the most interesting relationship. The introverted Drake, who overdosed on antidepressants fifty years ago this November, first met Hardy when he was a guest at a taping of BBC Two’s International Cabaret in London in the late-Sixties, compèred by Kenneth Williams. Drake was introduced to Hardy after she’d finished recording but plans to go for dinner fell through.

However, the French singer was an admirer of Drake’s work; she said she was moved by the “soul”, the romantic melodies and the melancholy timbre of Drake’s voice on his Five Leaves Left album. Drake’s producer Joe Boyd thought it would be a good idea for Drake to write a song for Hardy or for Hardy to cover one of Drake’s tracks. Drake himself was “cautiously open” to these ideas, according to biographer Richard Morton Jack. So the pair flew to Paris with arranger Tony Cox to meet Hardy.

The meeting didn’t go well, with Drake – perhaps starstruck – hardly saying a word. This didn’t stop him bragging about it to his mates in the pub back at Cambridge University. “I said to him, ‘Where have you been?’” recalls pal Rick Charkin in Morton Jack’s recent Drake book. “He replied, ‘In France with Fran?oise Hardy. She’s interested in recording my songs.’ I was speechless.”

Indeed Drake developed something of an obsession with Hardy, who recorded at the same studio as him, Sound Techniques on Chelsea’s Old Church Street. He took to visiting her at the studio or impulsively turning up at her apartment in Paris. Sometimes he’d ring in advance, other times not. She’d take him along to dinner with friends but admitted to finding the situation strange.

“It was so odd that he would show up like without warning… He knew nothing about me and I knew nothing about him, and we didn’t try to get to know each other better. Did he expect something? A word, a gesture, a step? What had brought him to Paris? Could he have come because of me? This last possibility never crossed my mind,” Hardy said. Morton Jack has a theory about why young genius Drake revered the French singer so much: she “represented a vital link in his sense of relevance as a musician”.

It wasn’t only British artists who were mesmerised by Hardy. Bob Dylan, who like Jagger had appeared with her on that 1965 Melody Maker cover, wrote letters to Hardy. She always declined to reveal what they say. He also wrote an ode to her on the back of his 1964 album Another Side of Bob Dylan. “For Fran?oise Hardy, at the Seine’s edge…” it started.

But it Blur’s Alex James who best sums up the late singer. He describes spending an “enchanted afternoon” with Hardy in her Paris apartment – all “black walls and exquisite treasures” – with his bandmates in the mid-Nineties. “She was a truly beautiful woman, around fifty, skinny as an elf and confident, yet delicate,” he wrote in his autobiography A Bit of a Blur. France doesn’t have a royal family, he noted, but if it did, she would be its “fair queen”. Given her love of all things British, she’d have no doubt approved.