How Mister Rogers' Life of Quiet Grace Turned Him Into an Unlikely Pop Culture Hero

Fred Rogers isn't your typical pop culture icon.

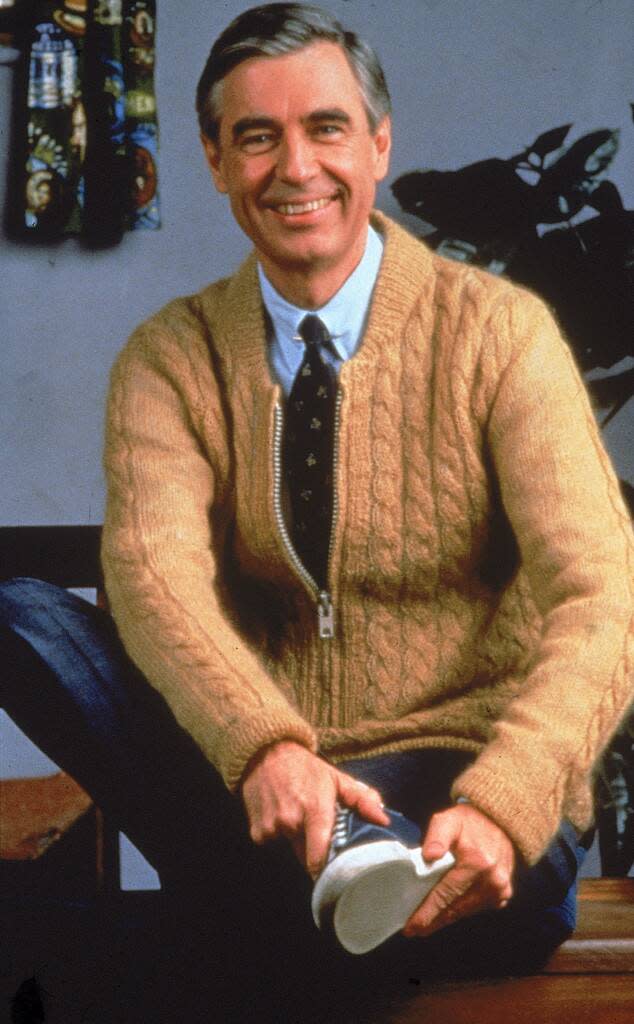

As the host of the long-running PBS children's program Mister Rogers' Neighborhood, he wasn't slick or sarcastic, hip or cool. He was sincere to a fault and spoke with a slow determination and a pure warmth uncommon for TV. Had his show still been on the air in the social media age, there's every reason to believe that Twitter trolls would've dunked on him any chance they got.

There's a whole generation of children who've come of age not even knowing who the man was, considering his show went off the air in August 2001 and he died only a year and a half later. And for the whole generations of children who did spend their formative years taking trips with the man into the Neighborhood of Make-Believe one half-hour episode at a time, well, they became adults, as all children hopefully do, and a fast-paced world full of distractions and cynicism pulled focus, forcing Rogers and his innate goodness to become something of a distant memory—twinkling, yet fleeting.

Documentaries That Made a Difference

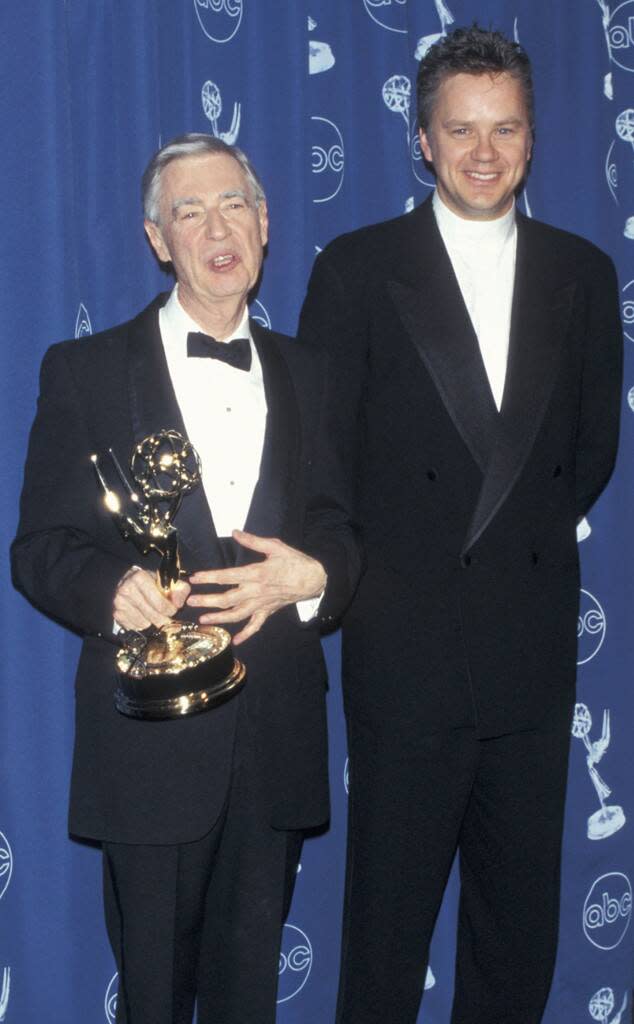

And yet, at a time when civility and kindness seem like four-letter words you can't say on TV, in a world gone stark raving mad, Rogers has emerged to be one of the unlikeliest pop culture heroes of our time. With a rapturously-received 2018 documentary Won't You Be My Neighbor? followed by a well-reviewed 2019 biopic starring Tom Hanks as the beloved figure, entitled A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood, Rogers' story continues to return exactly when we need it most, bringing with it a beacon of hope amid a sea of indifference and a gentle reminder that it doesn't have to be this way.

Before Fred Rogers became the hug of a man generations of children knew him to be, he was first, as all adults are at one point in time, a child. And like all those children who Rogers sought to comfort and make feel special as an adult, his childhood was a lonely one. Only, without a Mister Rogers of his own to turn to, the shy, introverted and overweight young Rogers, taunted by his classmates as "Fat Freddy" and often made homebound by childhood asthma, was left to his own devices.

"It was a lonely childhood," Won't You Be My Neighbor? director Morgan Neville told Entertainment Weekly. "I think he made friends with himself as much as he could. He had a ventriloquist dummy, he had [stuffed] animals, and he would create his own worlds in his childhood bedroom."

He also spent time with his maternal grandfather, Fred McFeely, who he was named after and who would go on to inspire the Mr. McFeely character made famous on Mister Rogers' Neighborhood—and who was also responsible for patiently imbuing in Rogers a sense of self-esteem. "You know, you've made this day a special day just by being yourself," his grandpa would tell him.

All superheroes have their origin stories, and that potent mix of childhood pain and gentle grandfatherly guidance was the blueprint for all that Rogers would become.

Tom Hanks Is Mister Rogers in First Look at You Are My Friend

After overcoming his shyness in high school, where he served as Latrobe High School student council president and editor-in-chief of the school yearbook, he studied music composition at Rollins College in Winter Park, Florida—where he met his future wife Sara Joanne Byrd, who he married in 1952, a year after graduation, had two sons with, and remained married to until his death in 2003.

With plans to enter seminary school after graduation, a chance encounter with an emerging piece of technology changed the course of his life. After his parents got their first TV set, the legend goes that Rogers did not like what he saw on the newfangled thing. "I was appalled by what were labeled 'children's programs'—pies in the face and slapstick!" he wrote in his book You Are Special. "Children deserve better. Children need better."

So he decided to do something about it.

"I got into television because I hated it so," he once told CNN. "And I thought ... there's some way of using this fabulous instrument to be of nurture to those who would watch and listen."

So, he headed to New York City, where he worked at NBC as floor director on a handful of shows before returning to the Pittsburgh area in 1953 to work as a program developer at public television station WQED, where he worked with Josey Carey to develop The Children's Corner, a show that featured many of the puppet characters who would go on to populate his later work.

"I really believe it was the power of the Holy Spirit," Rogers told The Washington Post in 1982. "I mean, what did my parents think about all this? Here I was, leaving New York and network television to come back to Pittsburgh to start working with puppets. It was all so vague. Why, in the beginning, we used to go into the studio and just sort of...play."

While at play, he also followed an earlier dream and attended Pittsburgh Theological Seminary, spending his noon hour for eight years until he graduated and was ordained in by the United Presbyterian Church in 1963. Along the way, he began studying with child psychologist Margaret McFarland, who shaped and informed much of his thinking about and appreciation for children. And rather than put all that studying to work, say, in the church, Rogers curiously kept the medium of television as his ministry, as it were.

Tom Hanks to Play Mr. Rogers in Upcoming Biopic You Are My Friend

In 1963, the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation sought Rogers out to develop and host a 15-minute black-and-white children's program entitled Misterogers. As he explained in his memoir, the offer for the show, itself born out of a segment in another program called Junior Roundup, came from the CBC's head of the children's department, Fred Rainsberry, who told Rogers, "Fred, I've seen you talk with kids. Let's put you on the air."

Misterogers ran until 1966, when Rogers acquired the rights and returned to Pittsburgh, taking the sets he'd developed in Toronto back with him to WQED. Renamed Misterogers' Neighborhood, the show began airing regionally in the northeastern United States until a lack of funding forced it into cancellation a year later. Immediately, the public outcry prompted a search for new funding and The Sears Roebuck Foundation stepped in. The new source of funding enabled it to be seen nationwide on National Education Television, the precursor to PBS and the slightly re-titled Mister Rogers' Neighborhood began airing nationally on February 19, 1968.

For the three decades it was on the air—with only a brief gap from 1976 to 1979 due to another funding issue, the show broadcast its last episode in 2001—Rogers never wavered in his sincere and simplistic approach. He eschewed the "bombardment" he saw coming from other children's programming, with their frenetic pacing and animation, favoring an unhurried pace. He wrote every script, composed every song. And he never dared shy away from complex social issues or real-world tragedies.

In the first year of the show's national run, he rushed a special to air only two days after the assassination of presidential candidate Robert Kennedy. "His funeral was televised nationally on Saturday and [Rogers] said, 'We have to get something on television before the children of America are sitting at home this weekend watching it and not understanding what happened,'" Neville told a crowd during a January The Envelope Live chat with the L.A. Times. It was that episode that convinced the director to tell Rogers' story.

"The world is not always a kind place," Rogers once said. "That's something all children learn for themselves, whether we want them to or not, but it's something they really need our help to understand."

Elaborating to CNN years later, he added, "I believe that those of us who are the producers and purveyors of television—or video games or newspapers or any mass media—I believe that we are the servants of this nation."

Along the way, Rogers' unflappable sincerity opened him up to mockery, with Eddie Murphy's "ghetto" version on Saturday Night Live perhaps being the most famous example. But it didn't faze the genial host. At least, not always. "I don't really mind the parodies of me as long as they're not hostile," he told The Washington Post. "I think some comedy can be downright hostile. And some of it can be dangerous. There was this radio disc jockey we heard about who was saying things like 'Now boys and girls, just go get your mother's hair spray and your father's cigarette lighter and I'll show you how to make a blow torch.'"

And it certainly didn't discourage him from being anything but his authentic self. "One of the greatest gifts you can give anybody is the gift of your honest self," he told Newsweek shortly before the show went off the air. "I also believe that kids can spot a phony a mile away."

Rogers was as fastidious in his personal life as he was with the crafting of his beloved program. Enamored with the number 143, linking it to the phrase "I love you" long before it became pager speak, he had the number stitched into his sweaters and maintained it as his weight for practically his entire adult life.

As journalist Tom Junod wrote in his iconic 1998 Esquire profile on Rogers, which formed the basis for the story of the Hanks-starring biopic, "Once upon a time, around thirty-one years ago, Mister Rogers stepped on a scale, and the scale told him that Mister Rogers weighs 143 pounds. No, not that he weighed 143 pounds, but that he weighs 143 pounds…. And so, every day, Mister Rogers refuses to do anything that would make his weight change—he neither drinks, nor smokes, nor eats flesh of any kind, nor goes to bed late at night, nor sleeps late in the morning, nor even watches television—and every morning, when he swims, he steps on a scale in his bathing suit and his bathing cap and his goggles, and the scale tells him that he weighs 143 pounds."

As Neville later told EWi, "It almost doesn't seem possible or real. It makes you kind of stop and think, 'Is that something people can do?' But it's a window into his incredible willpower. He had such a strong devotion to everything he did from what he ate, to what he did every day, to his program. I mean, he was a man of incredible routine. He'd wake up at 5 a.m. and read the Bible every morning, often in Hebrew or Greek. He would go to the Pittsburgh Athletic Club and swim a mile every morning. He just had this very kind of almost monkish lifestyle."

Eventually, just as he had plainly and compassionately explained to his young audience over the years, that body would begin to fail him, as all bodies are to do at one point or another. And in December 2002, he was diagnosed with stomach cancer. By February, he had died, less than a month before his 75th birthday.

In the years since his death, as the world has seemed to tilt out of control more and more, Rogers' words have repeatedly gone viral in time of catastrophe. After the horrific Sandy Hook Massacre in Newtown, Conn., his "helpers" quote returned to the zeitgeist, a temporary balm to an unspeakable tragedy and a reminder that, even in the darkest of times, there is still good to be found.

"When I was a boy and I would see scary things in the news, my mother would say to me, 'Look for the helpers,'" the quote goes. "You will always find people who are helping. To this day, especially in times of 'disaster,' I remember my mother's words, and I am always comforted by realizing that there are still so many helpers—so many caring people in this world."

But while Rogers' words were of comfort, his image still hadn't become that of icon, as Neville recalled during that The Envelope Live chat. "For the past number of decades, he's kind of the quintessential cultural punchline, and if you look at how he's mentioned, it's often as a punchline and he's kind of this two-dimensional milquetoast character," the director told the crowd. "Like most people, I did not think about him for decades [after watching his show], and if I did, it's because I was making fun of him too."

But when he watched one of the many commencement addresses given by Rogers over the course of his storied career, a switch flipped. "It was late at night and I watched it," he recalled, "and at the end of it, I was like, 'Oh, my God, this is the voice I'm missing. Nobody is advocating for these things.'"

And those things he was advocating for? They've never felt more vital. During the course of Mister Rogers' Neighborhood, Rogers' mission to make sure that each and every child watching knew, just as Grandpa McFeely made sure he knew all those years before, how special they were faced, at times, criticism that it was instilling an inflated sense of self-importance in the youth. But always, always, in his next breath, he reminded children that their neighbor was special too.

"The underlying message of the Neighborhood is that if somebody cares about you, it's possible that you'll care about others," he told Christianity Today in 2000. "'You are special, and so is your neighbor'—that part is essential: that you're not the only special person in the world. The person you happen to be with at the moment is loved, too."

It's easy to look at that sentimentality and write it off as mawkish, reduce it to a punchline. And for years, most of us have. But as unrest and division feel more like the rule and not the exception, it's hard to listen to Rogers speak and not feel, like Neville did listening to that commencement speech, that this could be the way forward.

"I think to many Fred's message does feel very distant from today's world," Nicholas Ma, one of Won't You Be My Neighbor? producers and son of cellist Yo Yo Ma, who was a longtime friend of Rogers, told Forbes. "But our belief is, when audiences hear it, it surges back into our consciousness, familiar and powerful. Because his ideas — that we all long to know we are loved and capable of loving, or that we are called to be 'repairers of the world,' not destroyers of it — are so fundamental and human that they can't be silenced."

In one of his last public speeches before his death, Rogers delivered Dartmouth College's 2002 commencement. He would be dead within the year, and yet, there he was, delivering his undeniable truth.

"Our world hangs like a magnificent jewel in the vastness of space," he told the captivated audience of graduates early in his 16+ minute speech. "Every one of us is a part of that jewel. A facet of that jewel. And in the perspective of infinity, our differences are infinitesimal. We are intimately related. May we never even pretend that we are not."

(Originally published on February 9, 2019 at 3 a.m. PT.)