Most people misunderstand Walter Anderson, son says. How a new book explains the artist

John Anderson sails as often as he can to Horn Island. It’s mandatory, he said, that he camps there at least twice a year. He pitches a tent and enjoys the beauty of the barrier island.

His father Walter Anderson, the famed New Orleans-born artist who lived in Ocean Springs, loved the island. Much of his work captured the odd beauty that inhabited the thin barrier island about five miles from Mississippi’s coast.

Walter died of cancer in 1962 when John was 18.

Few people really understood his father, he said. Walter was diagnosed with schizophrenia, but John disputes the diagnosis. But even he was somewhat estranged, he admits.

Walter camped in solitude for 25 years on the island, his son said, only rowing back to Ocean Springs when he ran out of supplies. He carried his painting supplies in the brim of his cap, John said, recounting the way his mother told the story. And that hat was often the only thing he was wearing.

“He was Adam in a hat,” John said, quoting what a scholar had called his father. “And Horn Island was his Eden.”

Many artists were creative because they were artists, John said, but his father was an artist because he was creative. Walter’s art alone tells his life story, his son believes, and everything else is just an opinion.

Two years ago John embarked on a journey, compiling his father’s personal journals and some art pieces into a book he believed could help with the “public confusion” surrounding how people viewed his father.

“I can still visit him anytime I want by visiting Horn Island,” John said; he started visiting Horn Island religiously during the writing and research for the book.

He believed many incorrectly tried to assign intrinsic meaning to his father’s work and misunderstood the sort of character his father possessed.

John said that his father’s work articulates his love for nature and humanity. It wasn’t much deeper than that. Much of it was left for the viewer’s interpretation.

“I can state categorically that Daddy was more creative and productive than most people,” John said. “The thing that distinguished him from other people was that he loved more than most people.”

That’s actually why Walter constantly visited Horn Island, John said. He cared for people too much, so he went to Horn Island to keep some distance. He always invited those he loved to go with him, John said; he wanted to show them his Eden.

John said many have portrayed his father as a victim of illness, by the unconventional way he worked. But John believes they misunderstood Walter’s worldview. He believes that was a symptom of his health and love for humanity.

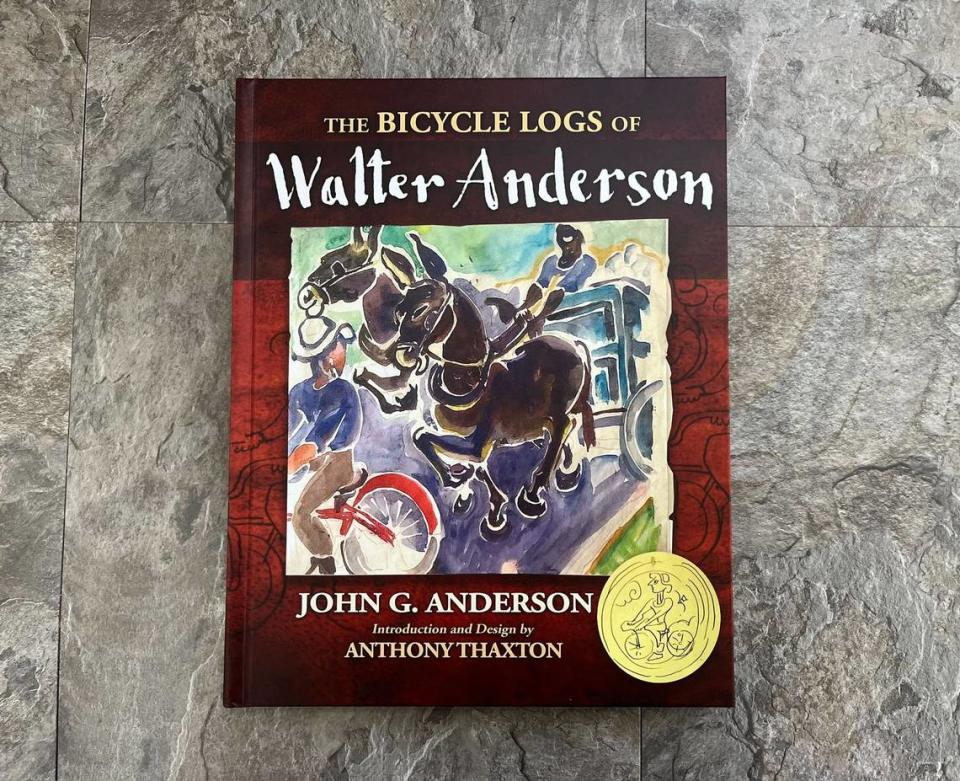

The book, called “The Bicycle Logs,” is now complete. An overhead look at the book might yield mild confusion to the insight John says it gave him. But through writing the book, John said, he feels closer than ever to his father.

He worked with the help of filmmaker and artist Anthony Thaxton to create the book. They compiled the personal journal entries, letters and relevant artworks associated with Walter’s many bicycle journeys. He biked to New Orleans, through Texas’ desert, to New York, through Costa Rica, through Florida and, famously, through China in 1949 seeking Tibet.

Walter had set out in search of like-minded people in Tibet, John said, but he never made it to the roof of the world. He was robbed while he was asleep on a rice paddy. And though he could see the mountains of Tibet, he was forced to turn back without ever crossing the border.

John said Walter kept a log of his adventures to share with his family and close friends. The book’s debut on June 23 will be the first time most of the texts will be seen by the public.

“A lot of people will just buy it and look at the images,” John said. “But that’s fine with me. The art tells the story.”