A music professor breaks down Sabrina Carpenter's Espresso

There’s an emerging consensus that Sabrina Carpenter’s “Espresso” is going to be 2024’s song of the summer. What makes it such a bop? Let’s find out!

There are a lot of alternate versions of the track out there: the extended “Espressooooo” version, the sped up “Double Shot” version, and my personal favorite, the slowed down “Decaf” version. The instrumental is called “On Vacation”, and the acapella is called “Mochapella”. Somebody in Island Records’ marketing department was very caffeinated that day.

The lyrics are not exactly groundbreaking: they tell us that Sabrina Carpenter is extremely hot and guys are obsessed with her. The fun is in the fractured grammar: “That’s that me espresso.” What does this mean? In this Vox explainer, Alex Abad-Santos says that it “sounds like a baby asking for a caffeinated beverage.” This is not necessarily a problem! Some of the best pop songs of all time are nonsensical.

Carpenter’s persona has a glossy professionalism that matches “Espresso”, a finely engineered product of the pop machine

See the end of Michael Jackson’s “Wanna Be Startin’ Somethin’” for a case in point. I also adore “Umbrella” by Rihanna, with the timeless lyric, “under my um-b-rella-ella-ella, eh eh eh, under my um-b-rella-ella-ella, eh eh eh.” In a song meant for dancing, the sound of the words matters more than their sense. When Carpenter rhymes “singer” with “finger”, giving both the hard G, she is communicating a playful vibe rather than any semantic meaning.

I had never heard of Sabrina Carpenter before this song came onto my radar. Like Ariana Grande and Miley Cyrus, she was a teen TV star before she was a singing star, and was already a show business veteran in her early twenties. Carpenter’s persona has a glossy professionalism that matches “Espresso”, a finely engineered product of the pop machine.

“Espresso” was written by Carpenter, Amy Allen, Steph Jones, and the track’s producer Julian Bunetta, best known for writing and producing a big swath of One Direction’s output. Jones and Bunetta seem to keep a low profile, but Allen was featured in a recent Variety article, and it portrays her as a professional at the top of her game.

She has been a writer on four different top ten Billboard hits this year so far: “Espresso”, another Carpenter song called “Feather”, Tate McRae’s “Greedy”, and Justin Timberlake’s “Selfish”. (All of these songs have at least four co-writers, which is common in the present pop landscape.) Allen has also written hits for Harry Styles, Olivia Rodrigo, Camila Cabello and various other artists more familiar to my kids and students than to middle-aged dads like me.

READ MORE

Beyond her songwriting for other people, Amy Allen is also a recording artist; her most recent solo single, “Girl With a Problem,” sounds more like indie rock or grunge than pop. How does one learn to be a successful pop songwriter? In the Variety piece, Allen describes a formative experience of long drives in her native Maine, listening to classic rock radio with her family. But many people have that kind of experience; the more germane part of Allen’s bio is that she went to Berklee, where she studied songwriting with Kara DioGuardi, who also taught Charlie Puth and Sam Fischer.

Why does “Espresso” sound so comfortingly familiar? My wife thought it sounded like European club hits of the late 90s, but those club tracks have their own origins further back. My friend Dan Charnas hears influences of the early 80s funk and soul that our age cohort grew up with. (Dan’s book Dilla Time is an absolute must-read for hip-hop heads.) He threw the question out to his Twitter followers, and suggests “Walking Into Sunshine” by Central Line as one possible origin point. The thread concludes that the real forerunner is Larry Graham's "Sooner or Later". Flipout placed the “Espresso” acapella on top of Larry Graham’s instrumental, and the fit is flawless.

On Pitchfork, Jeremy Larson offers an alternative origin theory, another dance floor filler from 1982: Carly Simon’s club hit “Why,” featuring Nile Rodgers and Bernard Edwards. Everything currently on top 40 radio sounds like 70s disco, and it makes sense that the next hot thing will be the synth and drum-machine-oriented 80s flavor of disco.

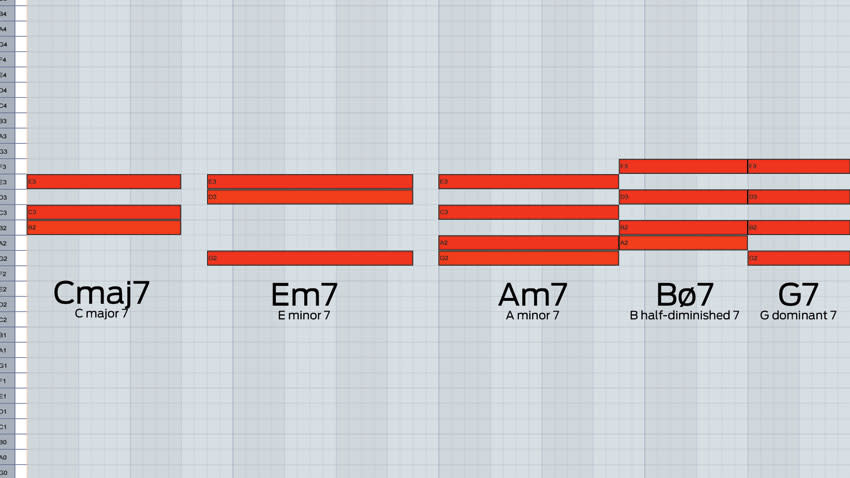

There is one big difference between “Espresso” and its early 80s predecessors: the number of instrument and vocal layers. Larry Graham’s “Sooner or Later” has a lead vocal, a few layers of backing vocals, and maybe five or six instrument tracks total. “Espresso” sounds it like it has about ten times that many tracks. There are ten or twenty tracks of vocals, and every instrument is multiply stacked, with different reverbs, panning, filtering and other effects. I love 80s disco, but it sounds thin compared to a dense slab of 2024 production.

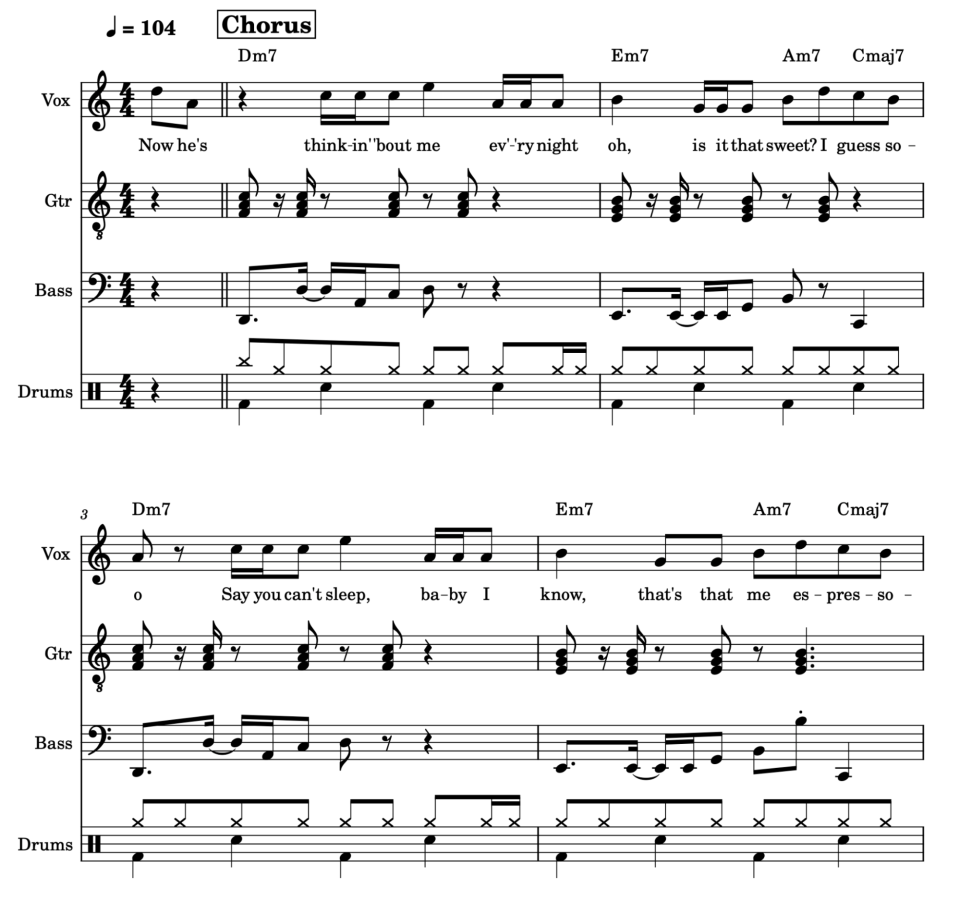

Imitating the vibe of early 80s dance music but with more expensive production is not enough to have a hit this big. What is going on beneath the surface of “Espresso” that makes it so compelling? Let’s start with the groove. The tempo is a laid-back 104 beats per minute, much slower than a typical dance groove. It has light sixteenth-note swing, a rhythmic feel you hear in funk and R&B more than in top 40 pop. That feel fits well with the early 80s R&B/disco production.

What is going on beneath the surface of “Espresso” that makes it so compelling?

After a vaporwave-flavored intro, the song begins with the chorus. The words “Now he’s” are a pickup at the end of the intro, and then the first downbeat of the chorus is empty! The line “thinkin’ ‘bout me” starts on beat two. Every phrase in the chorus melody is delayed to start on beat two. In the verses, the phrasing shifts even later, with the first accent in each phrase falling on beat four. It’s so hip! In the prechorus, the accents are half a beat before beat two and a quarter of a beat before beat four. Those are two extremely weak subdivisions, and that is not at all where you expect accents to be.

In The Musical Language of Rock, the musicologist David Temperley draws a distinction between beginning-accented and end-accented melodies. Beginning-accented melodies start at (or slightly before) hypermetrical downbeats, which is common. End-accented melodies conclude on a hypermetrical downbeat, which is uncommon. For examples of end-accented melodies, Temperley cites the verses of “Houses of the Holy” by Led Zeppelin and the chorus of “Like a Prayer” by Madonna. The melody of “Espresso”’ is very unusual for being end-accented all the way through.

What about the rest of the groove? The drums are mostly simple, kicks on one and three, snares on two and four, hi-hats on every eighth note. The bass dances around this predictable framework, accenting beats one, three and four, like the drums, but also hitting the subdivisions a quarter of a beat before and half a beat after beat two. There are guitar strums on these same subdivisions, as well as the one that’s half a beat after beat three. There’s also a subtle woodblock part scattered across yet other weak subdivisions. It’s not too wild or disruptive, but it’s more than enough to engage your ears.

READ MORE

Music theory you can use: How to create a chord progression from any melody

How about the harmony? It’s minimal, but it’s intriguing. The tune is in A minor, and every note in the melody and chords can be played on the white keys of the piano. This is familiar musical material, but it’s organized in an unfamiliar way. The chords are an endless two bar loop. The first bar in the loop, the hypermetrically stronger one, is on Dm7. This is the iv chord in A minor. The second bar in the loop is on Em7, the v chord. Notice that neither of these chords is the tonic. The melodic phrases in the chorus all end on A, which you would expect in a song in A minor. But those A’s don’t fall on tonic chords like you’d expect.

To make things more confusing, the bass does play the note A on the third beat of the second bar in the pattern, and C the fourth beat. That would normally imply an Am chord. But the guitar and keyboards ignore these bass notes, continuing to play Em7 on top. So are the implied chords here Am11 and Cmaj9? Or Em7/A and Em7/C? Or do the bass and guitar just not live in the same world for half a bar? I don’t know, but the ambiguity is cool.

How does the vocal melody fit the chords? It kind of… doesn’t. None of the notes clash, but they don’t feel particularly attached to the specific chords below them either. I tried the “Espresso” acapella over a few different instrumentals, and as long as they are in A minor or C major, it doesn’t really matter what the particular chords are.

Is “Espresso” a “good song”? Well, I can’t play it for my kids, who do not like f-bombs and are not ready to hear their beloved Nintendo Switch used as a sexual innuendo

This is a common feature of current pop music, described by another coinage of David Temperley’s: “melodic-harmonic divorce.” The melody and chords all belong to some key, but that doesn’t mean that they functionally agree. You can hear melodic-harmonic divorce in “Call Me Maybe” by Carly Rae Jepsen, “We Are Never Ever Getting Back Together” by Taylor Swift, and many other pop hits of the past couple of decades.

So is “Espresso” a “good song”? Well, I can’t play it for my kids, who do not like f-bombs and are not ready to hear their beloved Nintendo Switch used as a sexual innuendo. I’m sure my students know it and enjoy it in an ironic way, and I will get Cool Professor points for referencing it in class in the fall. Rick Beato decries corporatized songwriting by committee, but not every song has to have Leonard Cohen or Joni Mitchell levels of lyrical profundity. I can’t imagine having deep feelings about this tune beyond enjoying the groove, but maybe the groove is enough.