Jeff Lynne recalls how easy it was for ELO to take over the 70s

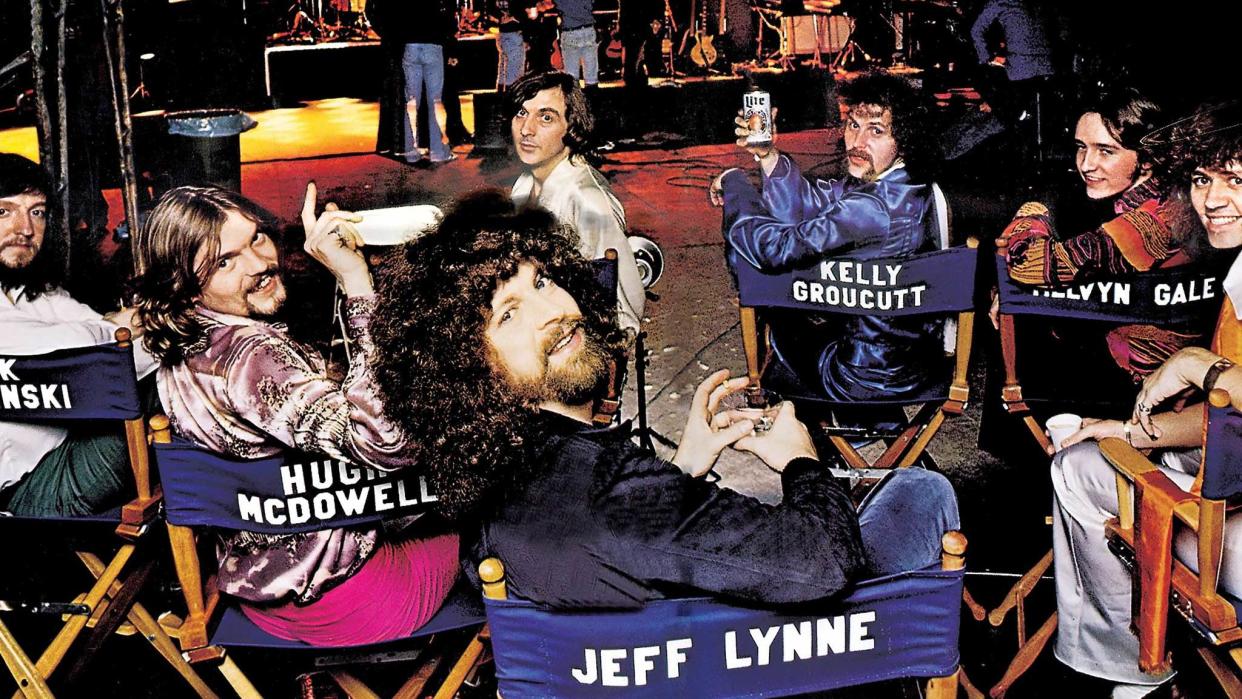

Jeff Lynne recently announced ELO’s last-ever tour. When the band played their first show in April 1972 he couldn’t have predicted the success ahead of him – and how easy it would be for him to write the songs that made his name. In 2016 he told Prog about the ELO’s formative years.

Only the wildly optimistic would have predicted from listening to Electric Light Orchestra at the start of the 70s that by the end of the decade, they would be one of the biggest bands on the planet.

Actually, the first track by the fledgling outfit, the Jeff Lynne-penned 10538 Overture (originally intended to be a Move B-side when it was recorded in July 1970), was a Top 10 UK hit, despite sounding, with its big cello riff, like heavy metal played by classical musicians, or hard rock chamber music.

Much of the rest of Electric Light Orchestra’s self-titled debut album was more progressive than pop. Look At Me Now was like Eleanor Rigby on downers. Nellie Takes Her Bow was a riot of discordant strings that could have been Bernard Hermann running amok with a rock band. Manhattan Rumble (49th Street Massacre) might have soundtracked a horror movie shower scene.

The Battle of Marston Moor (July 2nd 1644) brought to mind a 17th-century ELP, while Queen Of The Hours used violins less as a sweetener than a shrill counterpart to all the low-register sawing cellos. Only the projected second single from the album, Mr Radio, exhibited any of the qualities of the band who would later colonise the world’s hit parades. Issued in December 1971, the album faltered at No.32 – ELO’s highest-charting UK album until 1976.

Still, if it hardly augured well for their commercial fortunes, it was certainly a fine showcase for mainmen Jeff Lynne and Roy Wood’s prodigious talents. They may have had fellow founder member Bev Bevan on drums, timpani and percussion, Bill Hunt on horns and keyboards, Steve Woolam on violin, plus three cellists – but it was mainly Lynne and Wood’s show.

Lynne, who got involved in production on The Electric Light Orchestra, just as he did on the final two Move albums (1970’s Looking On and 1971’s Message From The Country), denies that the famously multifaceted Wood provided the inspiration for his multifarious contributions.

“Not at all,” he says on the phone from his home in California. “I was already playing quite a few different instruments. I took up the piano pretty much as soon as I joined [pre-ELO band] The Idle Race because I wrote most of the songs on the piano – I used to transpose them from the guitar. So I could play quite well after a few months, just by teaching myself.”

Lynne gives Wood credit for the cello part on 10538 Overture, played on a “Chinese cello that he bought for 40 quid”. But as Lynne points out, that cello playing, and his other contributions to that first ELO album, marked the end of Wood’s involvement with the band, give or take some bass and cello parts on two tracks from 1973’s follow-up album, ELO 2.

My dad would say, ‘The trouble with your tunes is you ain’t got no tunes.’ And I thought, ‘I’ll show yer, you bugger’

“His cello parts on 10538 Overture sounded fantastic,” he says, miming the jugga-jugga-jugga-jug riff. “And then he left after about six months to form his own group, Wizzard. That was the last time, really, that we hung out together.”

If Lynne is keen to minimise Wood’s inspiration, he does admit to loving Paul McCartney’s DIY job on McCartney (1970). Of course, The Beatles had always been one of Lynne’s primary influences. And he had first-hand experience of his idols while still with The Idle Race when he met them during the making of The White Album. Not that he heard any of the music.

“I didn’t actually listen to The White Album,” says Lynne of that fateful day in 1968. “I was invited to Abbey Road by an engineer I knew from where I was recording the first Idle Race album [Advision Studios]. But all I saw was Paul and Ringo in one studio and John and George in the other. They were really friendly, the lads, and there was George Martin, leaping around, conducting the strings for Glass Onion. I couldn’t believe I was there! I couldn’t sleep for days.”

One of the original aims of the Electric Light Orchestra was to take up “where The Beatles had left off, and to present it on stage,” so it must have come as a pleasant surprise when John Lennon himself rechristened the group “the sons of The Beatles.”

“Yeah,” acknowledges Lynne, very much the fan even after all these years, “that was rather a good compliment. I’ve still got that down on tape.” Was Lennon the Beatle he most admired? “I admired all of them, to be honest,” he says, diplomatically.

Despite handling many of the instrumental chores and all of the songwriting ones from ELO 2 onwards, Lynne denies being all four of the Fabs in one: “No, course not,” he says. “I think they beat anybody.”

Besides, he never had the advantage, even when Wood was still there, of having a head-to-head writing partner. “When Roy was in the group, we never collaborated,” he says. “We always brought our own songs in. We never sat round the same table and said, ‘Give us a bridge for this.’ That’s why The Beatles were so brilliant, because they had totally different styles blending in together. Whereas I’d make my own odd bridges and put them in.”

So Lynne had to push himself in the way that Lennon and McCartney would each other? “Yeah,” he allows. “I was always trying to find out how everything worked. It was quite amazing to be able to use a giant orchestra when I wanted to and have all that studio time.”

All credit to Lynne because he managed to replicate the Fabs’ diversity with little outside help. On ELO 2 there were harsh prog workouts, such as In Old England Town (Boogie No. 2), 11-minute anti-war tirades (Kuiama), pretty ballads (Momma), and Chuck Berry rewrites (Roll Over Beethoven).

“I would venture into all different types of worlds to make tunes,” he says. “You could do what the hell you liked. I did quite a few of those adventurous, ‘out there’-type things in those days.

“It wasn’t about ambition,” he adds. “The songs just came out that way. I think some of the real pop ditties we were doing in The Move were nowhere near as good as what we were doing in ELO because they were a lot freer. There were no boundaries.”

I was always surprised when anything did well. And they all started to do well at that point

Was he a prog musician with a pop sensibility, or vice versa? “I just liked spreading myself across the board,” he says. “I loved doing wacky things – progressive things, I suppose you could call them – but basically I’m a pop songwriter. As the years go by, I have become more interested in concise, shorter pieces.”

The third album, 1973’s On The Third Day, was the one with the Richard Avedon sleeve in the States where the famed photographer got the band members to display their belly buttons. (“I’ve no idea why,” says Lynne. “I just think he liked people’s belly buttons.”) The songs may have been mostly around the four- and five-minute mark, but it’s possibly ELO’s proggiest album, with titles such as Ocean Breakup/King Of The Universe on Side One and a continuous suite on the flip.

“I suppose that could be said of it,” concedes Lynne, who considers it “one of my favourite of our albums.” Did he meet any resistance from the record company baffled by the presence of concertos by Grieg (In The Hall Of The Mountain King) alongside neo-soul ballads?

“Not at all,” he says. “People used to accept what you gave them in those days. I remember doing the mastering of Showdown and the guy who did the edit said, ‘This has a real touch of class.’ I was really chuffed.”

There would be more praise as ELO’s music became progressively less progressive. Even his old man, a classical music fan, would be forced to concede that his son was on the right track. “I was concentrating on trying to get the melodies where I wanted them,” he says, his voice betraying more than a hint of Brum. “That was my dad’s criticism. He’d say, ‘The trouble with your tunes is you ain’t got no tunes.’ And I thought, ‘I’ll show yer, you bugger.’”

Eldorado (1974) may have had a loose concept about a daydreamer journeying to fantastical places to escape his boring reality, but it was ELO’s first bona fide pop album. It even contained a US Top 10 hit, Can’t Get It Out Of My Head. “I was always surprised when anything did well,” Lynne admits. “And they all started to do well at that point.”

The success of Can’t Get It Out Of My Head opened up doors for the band to tour America, under the watchful eye of their notorious manager, Don Arden, father of Sharon Osbourne.

“The first few tours were really exciting,” recalls Lynne, although he doesn’t recall Osbourne attempting to kick-start some on-the-road shenanigans – from a band she regarded as staid – by throwing a TV set out of a US hotel window. He laughs, perhaps thinking back to his impoverished upbringing. “No, we never did any TV-throwing – I’d rather nick ’em than throw ’em out the window.”

Back in Blighty, ELO’s upward trajectory continued apace with 1975’s Face The Music and singles Strange Magic and Evil Woman, which Lynne professes to have written in minutes.

“We were in the studio and I thought, ‘I ain’t got a single yet for this album.’ So I sent the other guys out to play football and said, ‘I’m going to make this up now in five minutes.’ And of course, I didn’t think I would, but I did – I went to the piano and those three chords of Evil Woman just came right out of my hand.”

Prog fans might also have noticed the opening track, Fire On High, with its symphonic grandeur, multiple sections and eerie backwards message, which was drummer Bev Bevan proclaiming, “The music is reversible but time is not. Turn back. Turn back. Turn back. Turn back.”

“I used to get stick for that,” he grumbles. “These weirdo guys – pseudo-religious people – said, ‘It’s all talking about the Devil!’ What a load of crap. If you say something and then play it backwards, it always sounds like that.”

The spaceship was great. At the end of the show I’d jump off the back of the stage and watch it closing…That was the highlight of the show

From then on, ELO could do no wrong – they bossed the second half of the 70s. A New World Record (1976) sold five million copies within its first year of release and included global hits Telephone Line and Livin’ Thing – testaments to Lynne’s ability to compress elaborate musical ideas into three and four-minute pop symphonies. “Tightrope is quite complex,” he agrees. “There’s quite a lot going on in those songs. I used to have a joke in the old days where I’d say, ‘I don’t stop till I can see through the tape.’”

Would he have just fiddled and fiddled if he’d been left to his own devices? “I would have, yeah. But I’m glad I didn’t now because it left the songs fresh. I only had a certain amount of time anyway: probably about six weeks to make an album, and a month to write it.”

True enough: 1977’s Out Of The Blue double-LP opus – the 10-million-seller featuring Sweet Talkin’ Woman, Turn To Stone and the Concerto For A Rainy Day, including Mr Blue Sky, that catapulted ELO on to a whole new level of stardom – was written in four weeks in the mountains of Geneva. And that included a period of writer’s block.

“The weather was crap for the first couple of weeks,” he remembers. “I didn’t come up with anything and I was down the pub all the time, this nice little tavern in the village. Finally, the weather cleared and that’s what gave me the idea for the words to Mr Blue Sky. Inspiration could come at any moment. And did, frequently.”

ELO’s subsequent tour was suitably spectacular, featuring an enormous set and a hugely expensive spaceship stage with fog machines and a laser display. Billed as The Big Night, it was the highest-grossing concert tour ever up to that point.

“That was fun,” says Lynne with an audible grin. “The spaceship was great. At the end of the show I’d jump off the back of the stage and watch it closing. I’d hide behind a barrier and it used to knock me out every night. It made such a bloody racket. There were jets of steam coming out, a ridiculous low rumble, and this big, loud classical music as it closed. That, for me, was the highlight of the show.”

Was that weird? The boy from Shard End, part of this Spielbergian extravaganza? “Heh heh, yeah. The thing is, though, it happens so gradually that it’s not a shock. It’s like, ‘Wow, it’s got better than it was last year.’”

Really, it couldn’t get any better for ELO. By Out Of The Blue and the follow?up, 1979’s Discovery, they were the biggest rock band on Earth, arguably rivalled only by fellow quasi-proggers Supertramp. Everything they released, everything they did, was a newsworthy event. Was Lynne aware of how mega ELO were?

“Not really,” he says. Perhaps he had learned by then to switch off – their commercial enormity was only matched by the critical enmity they faced as the punk and post-punk music press poured scorn on the band’s every lavish note.

“Obviously when you put out a record you hope it’s going to do well. I used to be very wary of reading anything in case it changed me or my thoughts about what I was going to do next. Some of the media were great, like Kenny Everett. But some were wicked. You got some reviews that were like, ‘Bastard!’”

Still, creatively speaking, did he feel as though he was on a roll? “Yeah, I really did,” he says. “I could do no wrong. Every song I wrote came together easily. It was just one of those patches – about five years’ worth. I was really lucky to go through that.”