"There are no words in any language to express how badly I feel about that night": The strange and terrible story of Great White, and the Station nightclub fire

It was the summer of 2011 and Alan Niven sat on the deck at his house in the desert, waiting as a small speck made its way up the road towards the town. Out here he could see for miles. They say that in the desert each man sees what he’s looking for. That was part of the reason he had come. Maybe this was his answer. The speck got closer, became a truck. There were two people in the cab. It made its way off the road and onto the track that led to the house. It drew up outside and a woman got down from the driver’s side.

She took a wheelchair from the back and unfolded it. The other door opened and from it slid a thin figure, skin and bone, crutches under his arms. With some effort, he lowered himself into the chair. For a moment Alan wondered, but then he caught sight of the face, the hawkish nose, the bandana and its shock of hair, and he realised. It was certainly Jack.

They hadn’t seen each other for 17 years. A lot had happened. Jack’s appearance wasn’t a complete shock. Alan had watched the YouTube videos of him on stage, when he’d fallen over and had to be helped to his feet. He’d heard a recording of an interview that was up there with ‘The Troggs Tapes’ for stupidity. He remembered the hundreds of gigs, the endless tours: five nights a week of suffering for a singer. The expectant arenas, the calls to the doctor, a shot of cortisone or prednisone to get him through. Years of that causes the bones to degenerate. Now Jack had legs as thin as pipe-cleaners, a big old distended belly and he’d been drinking vodka and orange all the way from Palm Springs.

For a long time they had hated each other, but then Jack had made a couple of pleasant phone calls, and living in the desert had given Alan time to think. “I may have despised the little fucker,” he says, “but I would have felt bad about myself. I thought, ‘Why don’t we open our door?’” Palm Springs was only a couple of hours from Prescott. He invited Jack out for the weekend. Jack’s wife, a nurse called Heather, drove them. Now Alan watched Jack struggle to wheel himself up the driveway and he thought, “This could be the last time I ever see you.” Maybe it was the moment when they would heal something, turn a page. Six hours later, Alan’s partner, who is also called Heather, astounded by Jack’s behaviour, threw him out of the house.

Mark Kendall was 17 years old and living in El Monte, California when he first met Jack. It was the summer of 1978, and he was looking for a singer for his band. They were called ZZYZX, although the name kept changing. Mark had been playing guitar since the age of nine. His father was a trumpet player, his mother a jazz singer, his grandfather a Vaudeville pianist. Mark was good at baseball too, a pitcher, but his shoulder had begun hurting after he threw fastballs, so he felt that music was the way for him.

Jack lived in Whittier, and his heroes were Robert Plant and Steven Tyler. Mark thought that he had some of their swagger and a great bluesy voice that sounded a lot older than he looked. He dragged Jack into another room at a rehearsal one day and showed him a couple of songs he’d written.

“Jack said: ‘Man, we should make a band playing this,’” Kendall says. “So we picked up his PA, went to his parents’ house and started.” They found a drummer called Tony Richards and a bassist named Randy Knapp and played around for a few weeks but then Randy took off. Other guys came and went. For a while they called themselves Livewire, then it was Highway. Mark had a job painting road signs. He was on his way to work one morning and had stopped at the liquor store for some cigarettes when he looked at the newsstand and saw a headline that read, ‘Jack Russell, Whittier-ite, shoots live-in maid’.

“I’m going, ‘Whittier… That’s where Jack lives… But it can’t be the same guy. He’s not going to shoot somebody, that’s crazy…’”

Mark crossed the street to a payphone and rang Jack’s mother. “I said: ‘That’s not the Jack I know, right?’ And she said: ‘Yup, that’s him…’ I started thinking, ‘This guy shoots people? What have I got myself into?’”

Jack was bailed before trial. He told Mark he’d been so high on PCP that he’d blacked out. He couldn’t remember shooting anybody. He suggested that they play a concert in the park ‘against PCP’ because it might get him a lesser sentence. They changed the band’s name to Wires and did the show.

“Next thing I know,” says Mark Kendall, “I’m seeing another newspaper headline: ‘Jack Russell, Whitter-ite, sentenced to eight years.’”

Mark felt like he was starting all over again. He put an ad in the paper and found a drummer called Tony Montana and a bassist named Don Costa. They gelled right away but they couldn’t settle on a singer. They had a guy called Butch who sounded like Rob Halford. Then they auditioned John Bush. He was great but he didn’t fit. Then they found a girl called Lisa Baker who turned them into something very different. Her father worked in TV and he organised a couple of industry showcases but before anything could happen with that, George Lynch came and poached her for his band Xciter.

George was the first guy that Mark saw tap the fretboard with both hands, but the guitarist everyone was talking about was Eddie Van Halen. Mark had watched Van Halen play a backyard party, admission one dollar. Now they’d signed to Warner Bros and had a record out. “I couldn’t believe that a band from just up the road signed to Warner Bros. It made me think that if they could do it maybe we could do it too, if we got really lucky. We just had to put ourselves in a position to get lucky.”

All of a sudden there were bands playing everywhere, all over the suburbs of LA at clubs and parties and in backyards. Mark, Tony and Don got Butch back in the band and played wherever they could.

“Then, after not even two years, they let Jack loose out of jail,” Kendall says. “I had a call from his mom. He was out on a furlough in a halfway house, then he went back. While he was on the furlough, he came and sang with the band. I liked it right away. Tony wasn’t sure. Costa said: ‘We’re gonna get more girls with this guy’. I really liked his voice.

“He told me he was not the kind of person that would shoot someone, he was just kind of super-high on this PCP. He said he blacked out and didn’t even know what he was doing.

“I didn’t know anybody who’d shot anyone, let alone been in a band with someone who had. In fact, I didn’t even know anyone who knew anyone who’d shot somebody. But he did seem like he’d changed…

“Jack’s strength is the pipes he was born with. What worked well was my guitar and his voice. I had this keen sense of melody. I would hum melodies to Jack and he would sing the words. He could imitate anybody. He could sound like Klaus Meine, Robert Plant… he could just mimic anyone.”

When he was six years old, Jack wanted to be an archaeologist, digging up dinosaur bones, but for his birthday he was given a Beatles album and he fell in love with the song Help, and the drummer Ringo Starr. He didn’t care that Ringo was a drummer, what he liked was that Ringo was a rock star: cheeky, funny, a hit with the girls. From that moment on, Jack knew that he was going to be a rock star too. It was fate. It was destiny.

By the time he was 11 he was already in a band. When he was 16 he met Audie Desbrow. He played in Audie’s band for a while but quit because they didn’t want to play original songs. This tall, freaky-looking guy called Mark Kendall kept calling him, but Mark’s band were cross-town rivals. He knew they were no good even though he’d never heard them. Jack was 17 by the time they hooked up and pretty into coke.

“At the time, we thought a real easy way to get it was to put some ski-masks on, we’ll get a gun, and we’ll go rob some dealers,” he says. “Unfortunately, the second time we tried to pull this off, I smoked some PCP and I blacked out. I’ll make a long story short, I don’t remember any of this, but this is what the police told me afterwards. I guess I shot through a door, the bullet hit a St Christopher medal on the maid’s neck and ricocheted into her shoulder. I was given eight years in court, but there was a bunch of clerical mistakes made and different things that happened and I ended up getting out in eleven months.”

Even while he was inside, he knew that his future was decided. Six days after he got out, the band played their first show. Their name was now Dante Fox.

“I was extremely focused after that,” says Russell. “In fact, I was focused in jail. I would tell people, ‘I’m gonna be a rock star’, and they’d be ‘Like, man you’re in jail…’ I remember years later getting some fan mail from people I met in there, saying, ‘Man, you pulled it off…’

“Some people are allowed a little peek at what their future’s gonna be. I kept looking at my watch thinking, ‘When’s this going to happen?’ I wasn’t real surprised when it did. I had to work at it of course. I wasn’t going to sit in my garage and hum and some guy’s gonna drive past in a Cadillac and go, ‘Who’s got that marvellous voice?’ I didn’t have illusions, but I always found the path to be reasonably easy. Even though there were hard times, I knew I just had to hold the course.”

Alan Niven was in LA working for a distributor called Greenworld. He’d had some success with M?tley Crüe’s first record Too Fast For Love. They’d sold 20,000 copies and Alan had helped the band make their deal with Elektra. Don Dokken brought Breaking The Chains to Greenworld and asked Alan to do the same for him. Greenworld weren’t the right fit, but Alan introduced Don to his friend Tom Zutaut, who was doing A&R for Elektra, and to Cliff Bernstein and Peter Mensch, and got him started that way. Alan and Don became good friends and shared a house in LA. Don told Alan to go and see Dante Fox.

“They were fucking abysmal,” says Niven. “They were ridiculous. The bass player was all in black. The guitarist was all in white. The singer was half in black and half in white. He had this big old hunting knife duct-taped to his arm. It was wannabe Halen-Priest. I went home. Don said: ‘No, you missed it. Look again.’ I went again and they were even worse. But I respected Don. I went again. They did Humble Pie’s …No Doctor as an encore, and Kendall just ripped the roof off the Troubadour. I asked them to bring over a tape.

“I decided to sign them to a label we’d just started. That was Aegean. AGN are my initials, you see. My first signing was Berlin, and I wanted Great White to be my second. Jack and Mark asked me to manage them as well. I told them that would be a direct conflict of interest. Jack looked at me and said: ‘You’ll learn’. I realised that if I didn’t have to deal with a dumbass manager… Fuck it. I stepped off that cliff.”

Mark Kendall was just ‘shockingly elated’ to be in a record company office, however small. “Alan could have told us anything,” he says. “He said the name has got to go. Jack didn’t want that. He thought that we’d lose all of our following. Alan said: ‘Don’t be concerned with those 70 people…’ It was so hard to think of a good name. Alan eliminates all that in 30 seconds and throws Great White at us: ‘The name’s no problem, I already got the name…’”

Alan wasn’t the kind of guy to sit back and wait for things to happen. He’d been to boarding school in England from the age of seven (“The first major trauma of my life. English boarding schools were all about the maintenance of empire. If you could fucking survive boarding school, there was nothing an Afghan tribe could throw at you that would be worse”) and then he’d worked for Virgin in London. In LA, his accent and his background set him apart.

“One of the very few times I’ve ever worn a suit and almost the last time I ever cut my hair was when I went to a probation meeting on Jack Russell’s behalf,” Niven says. “He was claiming he was going to be a singer and a rock’n’roll star and the authorities were taking a dim view of this. So I went in there with a suit on and said: ‘I have no doubt that with Mr Russell’s level of talent he will have a very productive career and future in entertainment.’ They saw the suit and heard the English accent, and they thought, ‘Well if this man says so…’”

One of Jack’s probation documents had what Niven calls ‘some very sarcastic and cynical language’ about Russell’s dreams and aspirations, so he used it as the inner sleeve for the Out Of The Night EP that Aegean put out. “When you’ve got something negative to deal with, get it out there and control it,” he says.

At first it seemed Alan and Great White could do no wrong. Niven persuaded two Los Angeles radio stations, KMET and KLOS, to playlist the EP. They went from appearing in front of a couple of hundred people to headlining at Magic Mountain to more than six thousand. For a week and a half they met major labels every day. Eight gave them written offers. They signed to EMI America, who had Queensr?che on their roster, recorded an album with Michael Wagener, came to Europe to support Whitesnake and toured the US and Canada with Judas Priest.

Yet even while they were making the record, something ate away at Alan. He knew Michael Wagener well – when he was over from Germany he’d spent several months living with him and Don and eating gallons of macaroni cheese at the house in Manhattan Beach. His calling card was his work with Accept and Dokken. “One of the most common directives I heard Wags give in the studio was ‘Make a fist Jack… Make a fist…’” says Niven.

“We didn’t have a big radio song,” says Mark Kendall. “Stick It was the mild hit with our fanbase, but when you’re getting played on MTV at 4.30 in the morning, it’s hard to have a hit. We sold 100,000 records or something, but it wasn’t what they were expecting.”

EMI America dropped them. Niven went back to the seven other labels who’d offered them deals. “I was utterly na?ve. I thought I’d have seven companies interested in taking a look at the situation. What I actually had were seven pissed-off bridesmaids who said that they weren’t good enough for us first time around.”

But he knew too that business wasn’t really the problem. “The record wasn’t good and the relationship [with EMI] was a disaster,” he says. “In the wake of that, I had to evaluate my involvement. I realised there would have to be some serious reinvention. We had to go back the beginning, and that was Mark Kendall playing …No Doctor. Let’s build on something with an English blues-rock sentiment. It’s got to have a fundamental integrity and be umbilically connected to the strongest aspects of the talent.”

For a few weeks, they sat around feeling sorry for themselves. “What we had, though, was a sense of family heightened by adversity,” says Niven. “Each one came to me and said: ‘If you stay, I’ll stay.’”

Alan got the money together for another independent release, Shot In The Dark. He gathered more radio play with a cover of the Angels’ Face The Day and got a deal with Capital Records, who were the parent company of the label that had just dropped them.

“I still don’t know to this day how Alan got Capitol to come and see us play when they were the father company of EMI,” says Mark Kendall. “How do you get dropped from a subsidiary and then the big guys come and say, ‘Yeah, we’ll have you’? I almost felt like, we’re destined here. People don’t get second chances. There was a lot of pressure for me to come up with music and it made me creative. It was do or die, and I knew it.”

The line-up solidified with the arrival of Russell’s old friend Audie Desbrow on drums and Michael Lardie, who’d been the second studio engineer on Shot In The Dark, on keyboards and guitar. Niven sent the band up to Big Bear for a week to work on material for what would become the Once Bitten album, but brought them back when he heard that all they were doing was getting fucked up.

They came home to the South Bay and the extraordinary, perhaps unprecedented, relationship between band and manager really began. Niven, who had some early songwriting credits with Great White because he’d essentially reshaped Jack’s lyrics (“Jack wasn’t very well developed in that area,” says Kendall), would now co-write all but one of the new songs. Beyond that, he had the sense of an aesthetic of what the band should be. He turned the sound into imagery, lyrics, album covers, videos – he understood better than anyone else what the band actually was.

“He had a vision. He was right most of the time,” says Kendall. “The only negative side for me a little bit was the intimidation. I started to feel a little bit like I was writing for his brain and not mine. It kind of narrows your range. But at the same time, he was right most of the time. What do I know? Alan liked straight-ahead rock’n’roll blues songs that would stand the test of time. He wanted the best for us and he had a lot of input. He picked up on the vibe, on something that was in us. That’s exactly what it was. It was easy for him to stand outside of our painting and figure it out. We were all inside, going, ‘Okay, now what?’”

Once Bitten was released in July 1987, the same month as Guns N’ Roses’ Appetite For Destruction. Alan Niven was by now managing both bands with his company Stravinski Bros. Guns N’ Roses had been signed to Geffen by his old friend Tom Zutaut but they had a bad reputation and Zutaut had almost pleaded with Niven to take them on. Alan got some synergy going between the two bands, piggybacking a couple of Guns’ video shoots onto the back of Great White’s, and getting Guns’ good support slots with Great White.

It was Great White that broke first, on the back of an eight-minute song called Rock Me, which was characterised by Kendall’s guitar solo. There was a longstanding ‘four minute rule’ for radio play, but Niven figured that if they put out a song that played for exactly twice as long, there were a lot of DJs who would want to call their girlfriends or take a piss while it was on. He was right.

Once Bitten and Appetite For Destruction were both certified Platinum in April 1987, in the week of Alan Niven’s birthday. Bobby Blotzer presented Jack Russell with his disc on stage at the LA Forum, where Russell had watched his first ever live show, Blue ?yster Cult, a decade before. Both bands went away on long tours. Although Great White were headlining, Mark Kendall and Jack Russell were in their way introverted and insecure characters who needed to ‘get outside of themselves’ to be up on stage on front of thousands of people each night.

“Because I know Jack so well, his confidence isn’t the way it has been perceived,” says Mark Kendall. “He was pretty insecure. I’m a pretty reserved person. We did what worked.” What worked was whatever drugs and substances it took to keep the fear of failure at bay. “We’d been through the experience of having those eight labels wanting to sign us, and overnight it disappeared,” says Niven. “I wasn’t going to have that happen again and I was going to keep things moving because this dark spectre was always five or six steps behind and you could hear the footfall.”

From 1986 until 1991, from Once Bitten to its double-platinum follow-up Twice Shy, that fear drove them forwards. Niven kept a diary with three columns in it: one showing where Great White were on any given day, one displaying where Guns N’ Roses were, and third where he was supposed to be. The bigger everyone got, the more the columns filled up, the greater the pressure became.

If Great White weren’t playing they were writing. If they weren’t writing they were recording. If they weren’t recording, they were rehearsing to go back on the road. With their first big royalty cheques, Niven had them buy apartments in the same complex. They were rarely there, but it offered a sense of permanence amongst the madness. Ever the rebel, Jack bought a boat instead, and moored it on the coast. Inevitably, though, a familiar rock’n’roll story began to play itself out. At its heart was what Alan Niven calls “Jack Russell’s incredible consistency and capacity for self-destruction.”

“It was kind of like having everything I dreamt about coming true tenfold,” says Jack Russell. “I nailed it. It was completely nuts. We were the kings of Hollywood. We thought we could run around town doing anything we wanted. I loved those years. I would get someone to drop me off on the Strip on a Friday night. They’d say, ‘How are you getting home?’ ‘Well, don’t worry. I’ll figure it out…’ Some crazy stuff happened. The band was really close, we used to dine together.

“There was a night when I was sitting in the back of my boat. It was a full moon. I was looking into the salon, which is the main room of the boat, and on the right hand side of the dash was my Platinum album for Once Bitten, and on the left side was the Gold record, and I sat back and I was drinking a Budweiser and listening to Cinderella, and I went, ‘Wow dude, you really pulled it off’.

“But I always lived for the day. Enjoy yourself, you don’t know how long you’re gonna be here. One hundred miles per hour, that’s the way I’ve lived my life, but the walls hurt when you hit them…”

“After you get a band rolling, the most delicate transition is from being a support band that everyone wants to a headline band that promoters want,” says Niven. “We took that step. We had MSG and a Finnish band I was working with called Havana Black and we put a tour together with Great White headlining. Off we went. One of the toughest places to sell tickets, because of economy and attitude, was the North-East, up around the Great Lakes area. And it was all sold out. The tour was working. They were going to make the transition. While they were crossing Texas and heading east, Jack went off the rails with his consumption of chemicals and artificial euphorics.

“It was a day where I’d carved out some time to spend with my son. I was going to take him to Disneyland. He was four, maybe five at the time. I went into the office that morning just to tidy up some essentials then we were going to drive out to Anaheim. While I was in the office I got a phone call and it was Audie, who was in Phoenix, Arizona. Not Texas. He was on his way back to LA, but he said: ‘You need to get out there and pick Jack up before he gets arrested.’ They’d both been thrown off a plane in Phoenix for being drunk and obnoxious. The first question in my mind is, ‘What the fuck are you doing in Phoenix?’ I called a friend of mine, Ray Brown who lived in Phoenix and used to make stage clothes for all the bands, and I said: ‘Do me a favour. Get down to the airport and find him for me. He’ll be in a bar’. I got to Phoenix and I went to Ray’s house. He answered the door and his eyes were as big as saucers, and I looked at Ray and I went ‘Oh shit…’

“I walked through the house to the swimming pool where there was this enormous cactus. There was Jack, sitting cross-legged in front of it. As I walked up behind him, I could hear him talking to the cactus. He turned around with a big, shit-eating grin on his face and he said: ‘Ah Niv, I got some shrooms for you as well…’ I had to cancel the tour and try and get him back in shape. The band never really recovered from that. Promoters were always suspect about Jack.”

Jack Russell remained an enigma to Alan Niven, even though their relationship was central to the future of Great White. “It’s a mystery to me,” Niven says of his behaviour. “I met his parents when they were alive. They seemed to be very decent people. I have a notion that a lot of people in rock’n’roll bands are trying to create their idea of a perfect family because they’ve suffered a dysfunctional one. Jack had really pleasant parents. And yet he exhibited a destructive criminal streak from his early teens.”

Success had concealed as much about the band as it had revealed. The first intimations of change were coming. Capitol’s new president Hale Milgrim appointed Simon Potts as head of A&R. Alan invited Potts to dinner. Potts turned up 45 minutes late and the first thing he said was: “You’ve got to explain something to me. Great White. How did they sell so many records? They’re not very good, are they?

Niven went to Milgrim and asked him to invite the band to the label’s landmark Tower to reassure them about their future. When they arrived, they were shown into a boardroom where there was one six-pack and a plate of sandwiches sitting on the table. “It would have been better if there was nothing,” says Niven. “It seemed to be a very premeditated fuck you.”

Their next record, Hooked, was more of the somewhat timeless blues rock that had separated them from most of the hair metal crowd, but such slim divisions were being washed away by Nirvana and the Seattle sound. The record’s cover, which featured a naked model being lowered into the sea on a giant fishing hook, was a mis-step that made them appear more out of sync with the times than they actually were. “You were looking at a smouldering crater where our music used to be,” says Jack Russell. “I was looking into it going, ‘what happened to our music?’

They would make one more record for Capitol, 1992’s Psycho City, an album deeply personal to Alan Niven, and probably the band’s best. In retrospect, its themes of betrayal are obvious in some of the song titles: Big Goodbye, Never Trust A Pretty Face, Love Is A Lie, Step On You. At the time, Niven was writing about the general and growing unease he felt in LA. Its subtext was yet to come.

Both Kendall and Russell had been through rehab. The band had homes and cars, but they weren’t a position where they could simply stop working and wait for the tide to turn back their way.

“I was sober during Psycho City and remained so for almost eight years, but the feeling was kind of impending doom,” says Russell. “All of a sudden, we weren’t playing arenas and we weren’t making as much money. You go from three million down to 750,000 [sales]. That’s like a little tap on the shoulder, you know.”

“It was more than indifference,” says Niven of the mood towards the sort of music Great White were making. “If you’d had success in the 1980s, it was tantamount to having leprosy. The most leprous moment was when the next album Sail Away came out. That was when I felt the most alienated from the atmosphere of the music business.”

Russell liked the songs on Sail Away but felt the sound was too lightweight. It sold a quarter of a million copies. The title song was a minor radio hit.

“I wasn’t happy,’ says Russell. “A change needed to come. There was one day Alan came up to me and said: ‘You need to stop moving around so much on stage. You’re getting a little old’. I knew we weren’t seeing eye to eye any more. The songs I’d come up with for Sail Away didn’t come across like I’d wanted. They were meant to be more Aerosmith-y. It was too light of an album. That’s when things hit the bottom. Alan and I had an argument about something I said in a magazine, and I said: ‘I don’t need you telling me what to say in a magazine’. That was the beginning of the end. I hung up the phone and told everybody I wanted to fire him.”

“The one thing that changed that they could effect was Jack deciding he couldn’t have the relationship with me any more,” says Niven. “It was entirely unexpected and it was immediate. He had the gall to come into my home with the rest of the band, where my family was, and said they didn’t want to work with me any more. I couldn’t throw them out of the house fast enough. I didn’t know which one I wanted to grab first. I said: ‘You fuck! You fuck off out of my fucking house now’. And that was it.

“At that point they owed me one and a quarter million dollars. I had a lunch with the lawyer and the accountant, and they signed over certain live masters to me. We had a settlement agreement where I was to get my share from the work I’d done from 1982 to 1995. It may be a self-serving observation but look at what happened next.”

For a while they seemed to be engaged in a race to the bottom. For Sail Away, Great White toured clubs. Their next record, Can’t Get There From Here, came out on yet another label, Portrait. They played a nostalgia package tour with Ratt, Poison and LA Guns. Mark quit the band in 2000, followed by Audie, who left with a tirade directed at Jack on his website. Jack announced the end of Great White on November 5, 2001.

Alan Niven had been fired by Axl Rose in 1991 and replaced by his former partner Doug Goldstein. Soon after he was fired by Great White, he discovered that his then wife had been having a relationship with Jack Russell for much of the time he’d been managing the band. The betrayals that he had sensed when he was writing Psycho City had revealed themselves to him.

“LA corrupts and Hollywood corrupts completely,” he says. “I found out about it [the relationship] and it illuminated certain things. Of course I laugh now because when I think of the creative content, how twisted is that? Look at the content of the songs and whose mouth it’s coming out of. In the last meaningful conversation I had with my wife she said something that rang true as the most honest thing she’d ever said to me: ‘What you don’t understand is that our marriage was a matter of convenient opportunity.’ It sent me into the pit of deepest depression. When you get to a point where you think every major relationship in your life is defined by betrayal, it sinks you.”

By 2003, his state of mind was such that he drove from the middle of Arizona to New Orleans; 1,600 miles in 24 hours. He wanted to leave everyone and everything he knew behind. He went to stay with a friend who he knew would ask no questions. He spent two weeks lying on a couch watching television and sleeping.

“My head was twisted and knotted. I was trying to lose myself in TV. I woke up one night and Jack Russell’s fat face is filling the screen. I thought, ‘what the fuck is going on here…?”

Jack was by now a solo act, and things weren’t going too well. He was playing clubs but sales were slow. He contacted Mark and asked him to help. Mark joined the tour. They played some Great White songs and some of Jack’s solo material and Jack billed the shows as ‘Jack Russell’s Great White’, even though it was just Mark plus Jack’s solo band. Sales picked up and the tour reached Rhode Island on February 20, 2003. They were playing at the Station nightclub, capacity 400. Jack spent a part of the day walking around town handing out tickets to make sure that the house was full.

The show began with Jack stepping out in a halo of ‘cold’ pyrotechnics as the band played Desert Moon. Mark had been wary of the pyro the first time he’d seen it, and Jack reassured him that it wasn’t dangerous to stand near. But when the tour manager Daniel Biechele set it off in the Station, the sparks landed on the soundproofing at the back of the stage and caught light.

A video of the gig, which with dreadful irony was being filmed by a TV channel as part of a piece on nightclub safety, shows Russell saying, ‘Wow, this isn’t good’, and trying to put out the flames with his water bottle. Most of the band escaped through the stage door. The audience surged towards the hallway at the main entrance and became trapped by the bottleneck. One hundred people died, more than 230 were injured.

The fire moved so quickly, engulfing the venue within five and a half minutes, that Mark didn’t realise that people were still inside. He even called his wife to say that the show might resume once the flames were extinguished. Jack stood outside giving interviews to local TV stations that had raced to the scene. It was these pictures that were being repeated across the US as the realisation of the scale of the Station nightclub tragedy, the fourth worst in US history, became apparent.

Like many other people, Alan Niven had woken up to find Jack Russell on his television screen. For an hour or so, as the broadcasts confirmed that the band’s guitarist had died, Alan thought that it was Mark. Only later was the name of Ty Longley, Jack’s solo player, who was 31 years old and an expectant father, released among the 100 names of the dead.

In December 2003, the brothers who owned the station, Jeffrey and Michael Derderian, and Jack Russell’s tour manager Daniel Biechele, were charged with 200 counts of involuntary manslaughter. A trial was scheduled for 2006, but before it began, and against the advice of his lawyers, Biechele entered a plea of guilty. In his statement he said: “I’m so sorry for what I have done, and I don’t want to cause anyone any more pain.”

In sentencing him to four to eleven years, the judge told Biechele, “the greatest sentence has been imposed on you by yourself”. At Biechele’s parole hearing in 2007, twenty of the Station families wrote to the court to express their support for him. As one family pointed out, “he made no attempt to mitigate his guilt”. He had written to the families of each of the victims whilst in jail.

The Derderian brothers pleaded no contest. Michael received the same sentence as Daniel Biechele, Jeffrey was given a 15 year suspended term. More than 11 separate parties with degrees of culpability in the fire have offered a total of $175m to the families in the form of compensation, with further settlements still to be made.

Those are the facts, but the matters of blame and guilt for such an overwhelming tragedy cannot be contained by the law. Great White undertook a benefit tour, the proceeds of which went to the Station Fire Memorial Foundation. Their insurers settled for the maximum sum payable under the policy, which was reported by the press as $1m.

Relations between Jack Russell and the Station families have been strained. Many were upset by his apparent insensitivity in undergoing a televised facelift, and by announcing a benefit concert to mark the tenth anniversary of the fire which they felt was calculated to boost publicity.

Russell went ahead with the show. Thirty people came, and $180 was raised. The Foundation has refused to accept the money, or any further funds from Jack Russell or Great White, a decision that Mark Kendall supports.

“If you want to donate $180, just write a cheque,” he says. Kendall has become friends with several of the survivors of the fire and their families in what he characterises as mutually supportive relationships.

“I can’t imagine a more horrific death,” says Alan Niven. “The horror of it. Great White is something I’m umbilically connected to for the majority of my creative life. You’ve got this awful feeling in the pit of your stomach. You even think, ‘Those people were only there because I pulled the assholes out of a bar in Orange County in 1982. A hundred souls would still be here if I hadn’t’. It goes through your head.

"I was fucking furious. I didn’t want to talk to any of them. I thought it was an act of inane vanity to let off pyro in there. I still feel the same way. I still feel it was an utterly stupid thing to do. The anger subsides because you realise that it wasn’t a malicious act. It was not something designed to create all of that horror and death.”

When Jack Russell speaks to Classic Rock about the fire, he cries, and takes time to compose himself. “Tragedy is almost cheapening it,” he says. “There’s nothing I could ever say, there are no words in any language to express how badly I feel about that night. I lost a lot of friends, and some really close friends. People who were coming to see us for twenty years.

"I remember watching the news on TV the next night, and they were showing pictures of the people that were lost and there was not one that I did not recognise. I remember them when they were little kids… pardon me… It’s something that never goes away. I’ll sit here on my boat some mornings and think, ‘There’s 101 people that aren’t here to see this sunrise’.

“After it had happened, I just thought, ‘That’s it, we’re never going to go and play again’. How can we go and play again and smile when 101 people are dead and so many others injured, how could you do that? You look over, you don’t see your guitar player there because he’s dead. Then the idea of the benefit tour came along, and it was something that was not entirely altruistic but as close as you could get. We tried to help out the families. We went out and did the best we could. That’s as much as I can say.

"It really affected my life in a lot of ways, but I can’t complain because I’m alive. My demons are my demons, and at that time, they were coming and going as they pleased, but that just took me to my knees. There’s no psychologist you can talk to, and trust me, I’m still talking to them, who could ever help me come to terms with that and go, ‘Okay, I feel better now’. Because I don’t. I don’t feel better about any of it and I don’t think I ever will.”

Russell is aware that some of the families feel that he has not accepted any culpability for the fire. In a report on his plans for the 10th anniversary show, the Boston Globe called him “a vilified figure” and quoted Chris Fontaine, whose son died and daughter was badly burned at the Station: “I think it’s so unfortunate that [Biechele] took the rap and not Jack Russell.”

The report went on: “Russell’s lawyers say he wasn’t charged because his actions were not criminal: He did not ignite the pyrotechnics, he had no financial interest in the club, and he had no role in installing the flammable foam. Russell also maintained that the band had permission for the fireworks.”

Jack Russell’s health has not been good. After a serious illness in 2010, he sometimes walks with a cane, and for a while wore a colostomy bag. When he visited Alan Niven in the summer of 2011, he was still in a wheelchair. But he is back living on his boat, and he says that his strength is returning. He is clean and sober, and a recent health check was positive about his future.

“I’m pretty good,” he says. “I had a physical in December and everything’s checked out. I needed a lube job, but that’s checked out…”

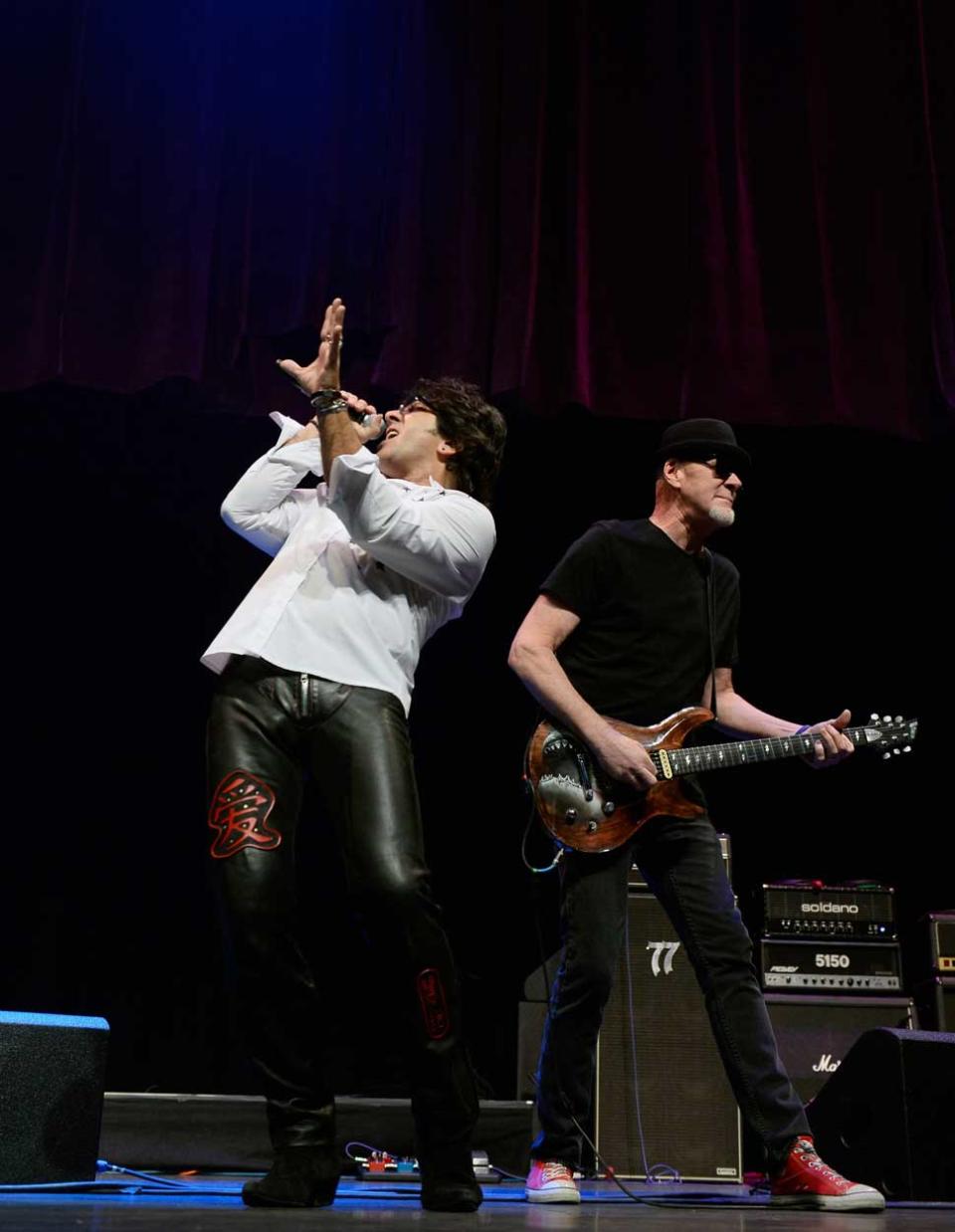

He and Great White, who have reformed with singer Terry Ilious and released a rather good record, Elation, in 2012, are engaged in a fractious lawsuit over the ownership and use of the Great White name. Alan Niven also gave a deposition in the case, which is now subject to court-ordered mediation. Leaked documents, and even a recording of one furious argument, have demonstrated the depth of feeling on both sides.

“Going through a lawsuit is quite possibly one of the worst things I’ve ever done in my life,” says Russell. “It’s one of the most stressful, hurtful things you can go through. So many things get said, trying to sway people to one side or the other. Memories get changed, people try to rewrite history. Old wounds come to light. It’s not something I’d recommend people go into lightly, but what’s right is right and you just need to plod along.

“I’ve always been an optimist. Whatever way it works out, it’s in God’s hands. I’m just happy I have my voice. I’ve made it to 50 when there was some question about that. Aside from all the stuff that’s going on right now, I think Great White was singular in a lot of ways. A real bluesy rock’n’roll band. The world’s biggest backyard party band. Great White was a great rock band.’

Alan Niven reconnected with Michael Lardie in 2006 (‘he was brave and decent’), and with Mark Kendall a couple of years ago. His aborted reunion with Jack left him feeling slightly rueful, but his life now is far removed from his time in LA. His marriage to Heather, an artist who had little notion of who Great White and Guns N’ Roses were when they met, has been a salvation, and their company Tru-B-Dor is working with metal band Storm Of Perception and Welsh blues guitarist Chris Buck.

Yet as he says several times, his ties with Great White are umbilical. In a way, their music and image are as much his life’s work as they are Jack Russell’s or Mark Kendall’s. Their musical legacy, which is significant and which stands apart from many of the bands of their era, has been re-framed by the tragedy of the Rhode Island fire. That’s something else that they have to come to terms with.

“I got to a point of all dreams being realised,” says Niven. “And then you have to evaluate whether those dreams were profound or of significant worth. When he’s in the right state of mind, Jack can be the most delightful company. He’s not an artist but he was and is a great entertainer. Will I ever trust him? I very much doubt it. I think we both made a decent effort to deal with the baggage. To find a way to be forgiving is healthy for me.”

This article originally appeared in Classic Rock 186, in Summer 2013. Terry Ilious left Great White in 2018, and was replaced by Mitch Malloy. He was followed by Andrew Freeman, and in 2022, Brett Carlisle became the band's fourth lead vocalist since the separation with Jack Russell. The same year, America's Deadliest Concert: The Guest List, a documentary about the Station nightclub fire, was released.