Notorious B.I.G. and The Doobie Brothers have nothing in common - except great books out this week

There isn’t anything in common musically or stylistically between The Doobie Brothers and the late Notorious B.I.G.

But both the persevering rock band and venerated rapper have noteworthy – albeit divergent – histories worth sharing.

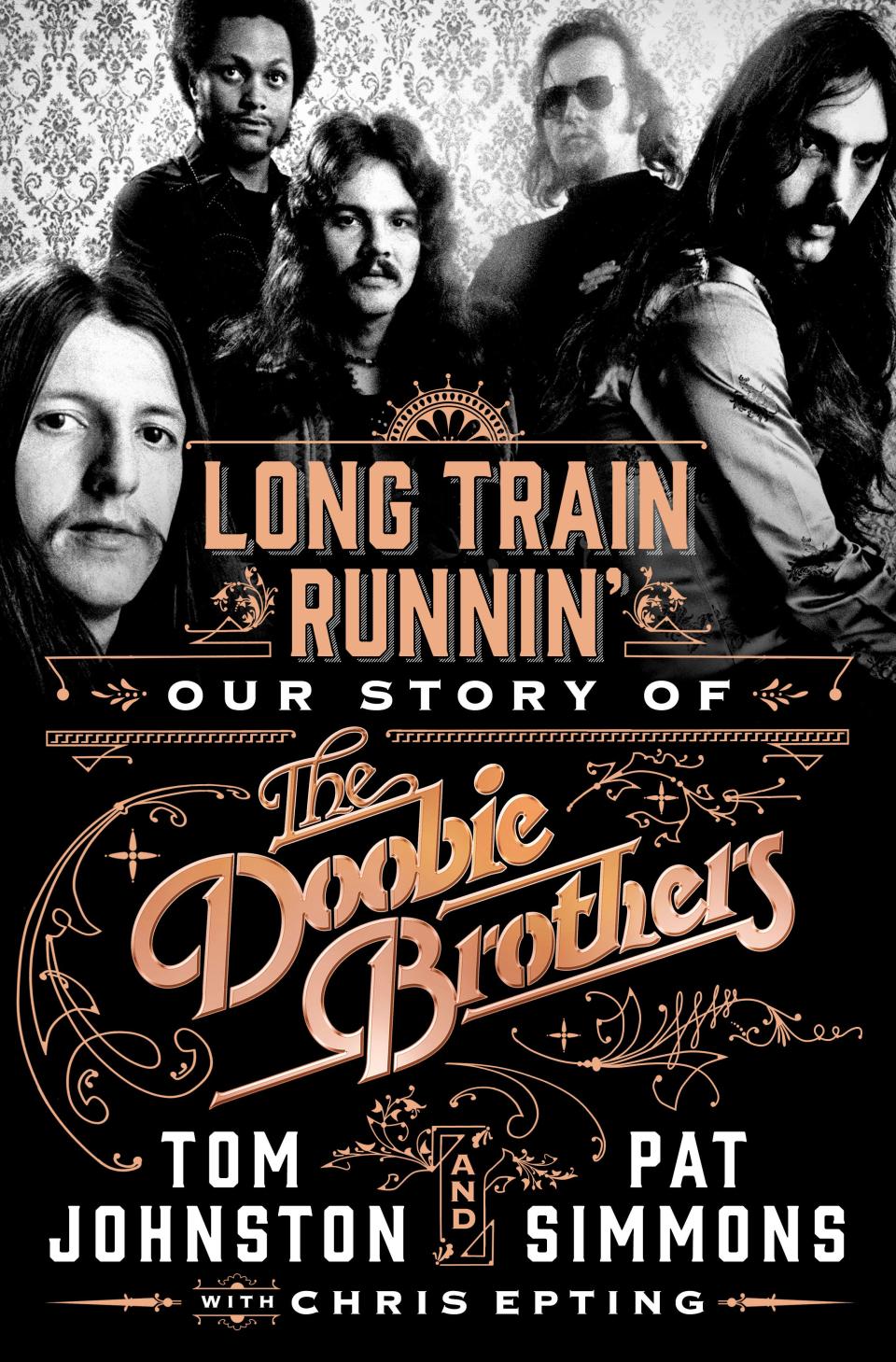

“Long Train Runnin’: Our Story of The Doobie Brothers” (St. Martin’s Press, 368 pp.), written by the band’s Tom Johnston and Pat Simmons with author Chris Epting, shares personal stories – often the same event told by various members – as they recollect their 50-plus year career.

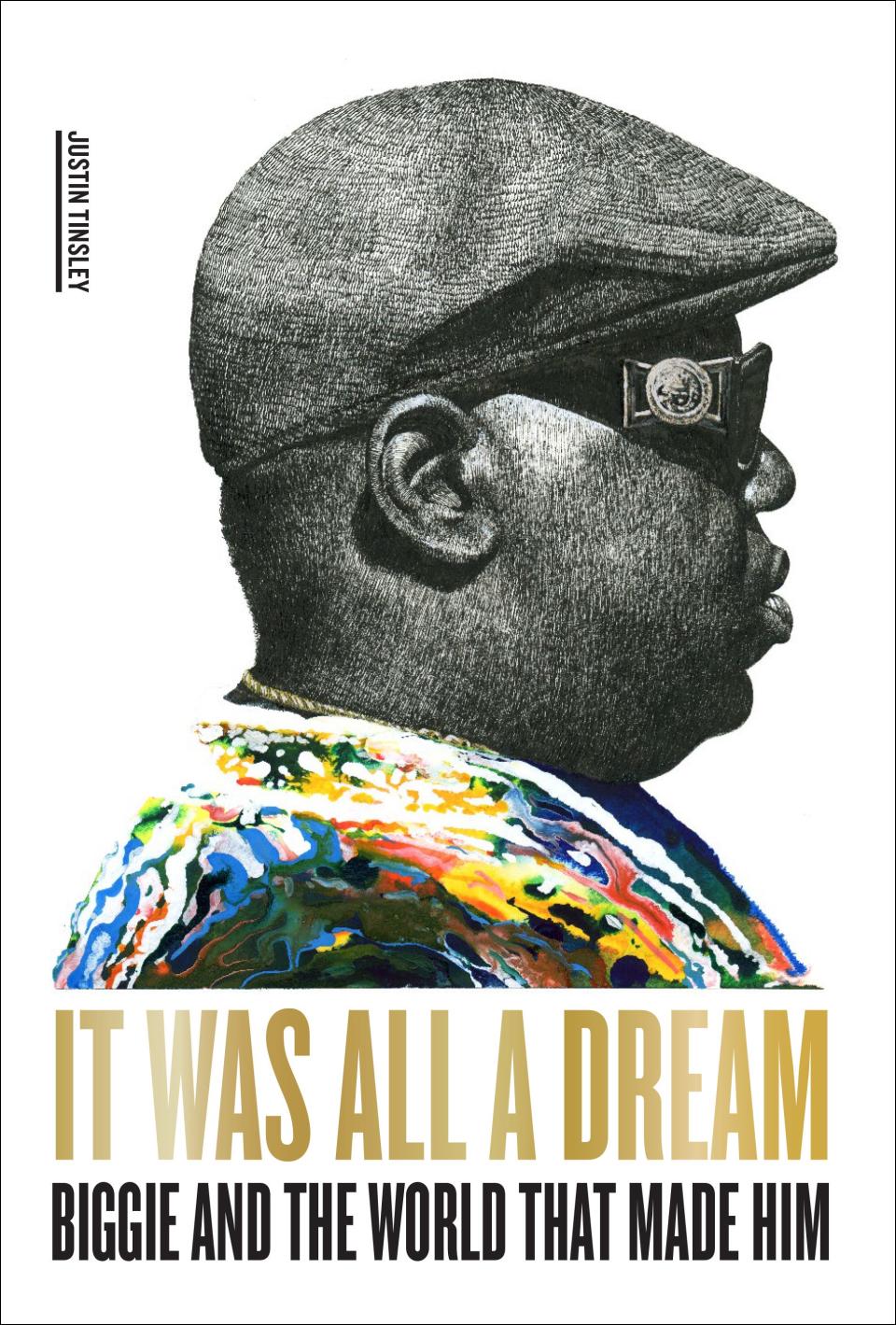

“It Was All a Dream: Biggie and the World That Made Him” (Abrams Press, 352 pp.), is a deeply reported saga of the ephemeral, yet colorful life of The Notorious B.I.G. (aka Biggie Smalls, aka Christopher Wallace) written by culture and sports reporter Justin Tinsley.

Here are some essentials gleaned from each:

The Doobie Brothers

An unlikely double bill

No one would necessarily peg the stew of rock, country and soul generated by The Doobie Brothers to mesh with the flashy glam rock pioneered by Marc Bolan and T. Rex.

But in 1972, around the same time that the Doobies’ “Listen to the Music” was positioning itself as the band’s first big hit, they were tapped to tour with Bolan and his “Bang a Gong (Get It On)” crew.

Johnston acknowledges that not only was the band treated extremely well as the opening act, but the flamboyant style and showmanship of Bolan “taught us to step up our stage show and stage presence.”

Following the tour, Johnston, Simmons and John started shopping at Jumpin’ Jack Flash in New York City, a vintage clothing store well-regarded within the rock ’n’ roll community for its decorative platform boots, shimmery skin-tight pants and other glamorous outfits.

In true full-circle fashion, both The Doobie Brothers and T. Rex were inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in 2020.

Sheryl Crow talks sexual harassment, depression in new documentary

'Black Water' rises

The vivid storytelling that unfolds during the band’s distinctive 1974 hit “Black Water” was crafted from an observational approach.

During a tour of the South, Simmons took a streetcar through the Garden District in New Orleans, watching the sun peek out during a rainstorm. He grabbed the pad of paper in his pocket and scribbled, “If it rains, I don’t care, don’t make no difference to me/I’ll take the streetcar that’s going uptown.”

As he waited for his clothes in a laundromat, he started thinking about the Mississippi River (“Mississippi moon won’t you keep on shining on me”) and later visited the French Quarter to listen to Dixieland bands (“I wanna hear some funky Dixieland”).

“Like a tourist, I wanted to reflect on it,” Simmons writes.

A new member, a new sound

After Johnston was forced to leave the band’s tour in 1975 due to severe ulcers, Doobie guitarist Jeff Baxter suggested a young man whom they knew from singing backup with Steely Dan to sit in while Johnston convalesced.

The “shaggy-haired, bearded background singer” was Michael McDonald, who integrated seamlessly into The Doobie Brothers. The band quickly realized that between McDonald’s soulful voice and ace keyboard skills, “he was much more than just a background singer.”

All of the members praise McDonald’s professionalism and easygoing personality – the universe dropped in the right guy at the right time – while McDonald humbly credits the band’s immediate need for a new player as the reason for his quick integration.

Following the tour, the band returned to the studio, where McDonald shyly brought them a song he’d been toying with – “Takin’ It to the Streets.”

“Little did we know that another Doobie Brothers era was beginning right before our eyes,” writes Simmons.

The Notorious B.I.G. (aka Biggie Smalls)

A most important basement party

One standout quote from Biggie – “Get to know me, man. To know me is to love me” – follows Tinsley throughout his recounting of the life of a talented, complicated rapper mysteriously gunned down.

But the origin story of Smalls, a drug hustler with a talent for wordplay, vibrantly details the scene of a “marijuana-smoke-clouded basement” that held two turntables and a microphone.

Smalls was a novice, but at this ad hoc party, he “rhymed with the confidence of (Big Daddy) Kane, the fearlessness of Ice Cube and the precision of Rakim… his flow lived in the vein of every beat.”

Inadvertently, Smalls had created his first demo tape that would lead to his lauded 1994 debut “Ready to Die,” on Sean “Puffy” Combs’ then-new label, Bad Boy Records.

Kendrick Lamar morphs into Ye, Will Smith in new video

The Tupac connection

Even though they will always be eerily united by similar deaths – Tupac Shakur was gunned down in 1996 at the age of 25 and Smalls was shot to death in March 1997 at 24 – Tinsley wants to remind us of the mutual admiration between the two.

Shakur was a huge fan of Smalls’ “Party and Bull(crap),” and upon hearing Smalls was in town at the same time in California, raced down to meet him at his hotel.

“It was almost as if from the moment they saw each other in person that for the first time, the two Gemini twins (‘Pac was born in June 1971 and Big 11 years later), became instant friends,” Tinsley writes.

A party at Shakur’s house spawned a moment in rap history witnessed by few – Smalls and Shakur breaking into a cypher (an impromptu gathering of rappers).

“’Pac would spit for 15 minutes, then Big would spit for 15 minutes… the most incredible day in my music-and-fashion industry life,” says celebrity stylist Groovey Lew, who was in the room where it happened.

The mystery shooting

The night of Smalls’ 1997 death is reported in harrowing detail, from the celebratory after-party for his “Hypnotize” single to Smalls and his entourage departing to another party in the Hollywood Hills in their GMC Chevy Suburbans.

As the group rolled onto the streets, Combs’ car went through the intersection of Fairfax Avenue and Wilshire Boulevard. Smalls’ got caught at the light. A black Impala pulled beside the vehicle, the driver holding a .40-caliber automatic handgun.

“Before anyone in the car could react,” Tinsley writes, “the heinous deed was already done.”

Smalls’ friend, Damion “D-Roc” Butler was in the back seat of Smalls’ car with rapper Lil’ Cease.

“(Big) didn’t say a word. He didn’t even say ‘ouch.’ Nothin’. All he was doing was breathing hard,” Butler recounted.

A race to Cedars-Sinai Medical Center proved fruitless. Smalls was dead.

Tinsley adds another heartbreaking detail. A few weeks prior to Smalls' death, members of the Bad Boy Records team had checked on a custom-made car with bulletproof armor. They decided not to buy it.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Notorious B.I.G., Doobie Brothers books are essential music reading