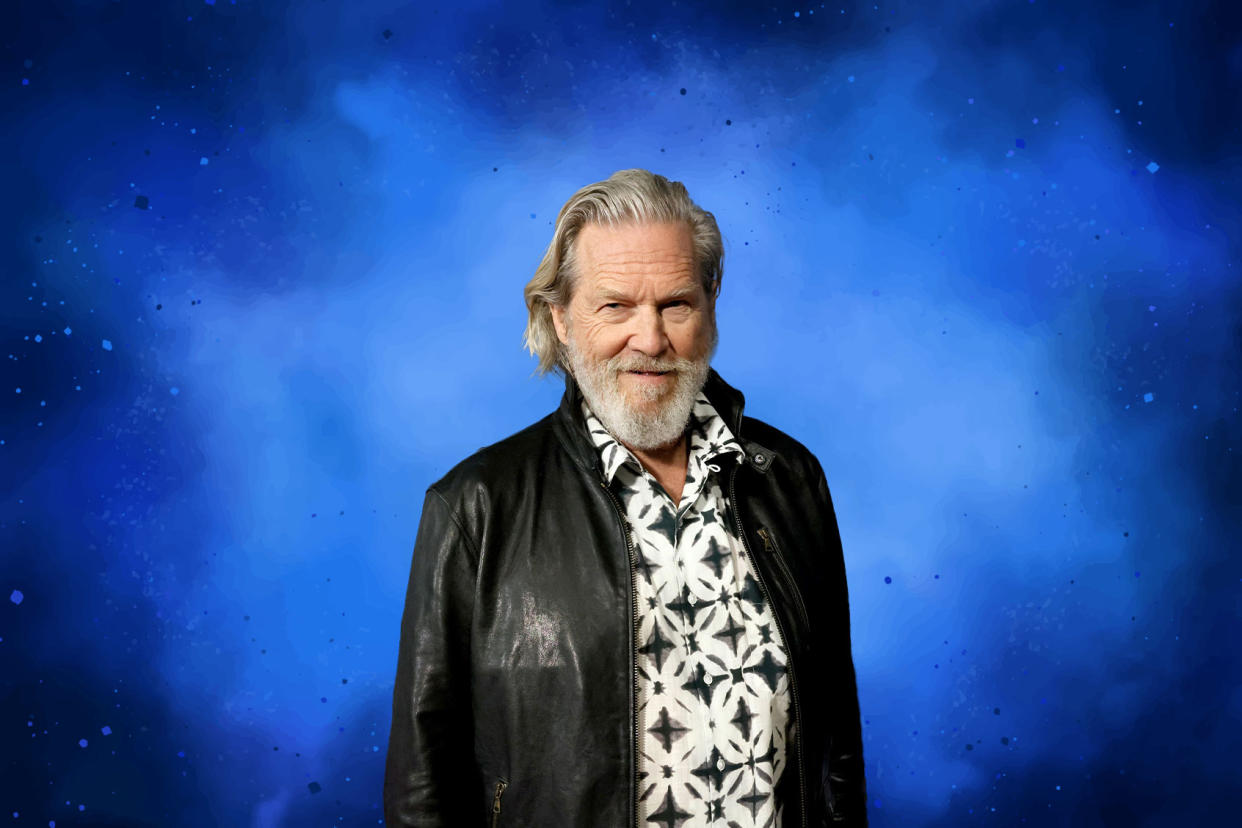

"The Old Man" star Jeff Bridges: "I didn't think I was going to work again"

Jeff Bridges really is that chill. Within minutes of our meeting for the first time, he is recommending meditative breathing techniques and calling me by the name I reserve for close friends. And by the time he's left our "Salon Talks" interview, I've also received a big, encompassing hug, because he's a hugger.

Though he has played psychopaths and Marvel villains, there's every good reason to understand why Bridges' most iconic role is as The Dude in "The Big Lebowski." It's because no one else could have embodied a character with such a convincing level of easygoing wonderment, and done so with Bridges' seemingly effortless commitment and precision. "That movie has bloomed in beautiful, beautiful ways," he says.

Now, after enduring non-Hodgkins lymphoma, a life-threatening bout of Covid, and a few entertainment industry strikes, Bridges is back at last for the second season in his Emmy-nominated role as resourceful, brutal former CIA agent Dan Chase in FX's "The Old Man." The Academy Award winner dropped by Salon's studio to talk about doing action scenes in his 70s, carrying the mantle of Dude for Kamala, and how recovering from his health scare got him to "fire up the old man again." The secret to his survival, in health and in Hollywood? "The L word, love," he says with a chuckle. "That corny thing."

This conversation has been lightly edited and condensed for clarity.

It's been more than two years since the last season of "The Old Man" and we pick up right where it left off. For those who need a refresher, where are we with Dan and his journey?

[My character] Dan finally gets together with John Lithgow's character, Harold, and they're off to Afghanistan to find their daughter. We left season one with him walking from the airport to the plane, and we open up and they're in Afghanistan, and the adventure begins.

This is a high-energy project for you "old dudes." I want to ask what that feels like for you. This is physically demanding, this is travel, it's intense. What do you do to prepare for a role like this?

Well, work out, do a little training so you can do some of the stuff that's required, which is a lot of fighting. Fortunately, we have Tim Connolly as our stunt coordinator and he's just so great to work with. Also, Tommy DuPont, my stunt guy who we've worked with in several pictures together. The basic assignment for a fight scene is like any other scene that you're doing where you want it to be interesting, but at the same time look very real and like it's happening just for the first time. In a dramatic scene, that's what you're going for, and that's what you're going for in a fight scene. Everything we're doing is an illusion. We're pretending, right? But we want it to seem as real as possible. To make that illusion, you practice, you figure it out. It's like a dance routine. You work it out and then you make it seem like it's happening for the first time after all of that work.

This is really the little show that could, because you began production in 2019. It gets shut down for COVID. Then you unfortunately get diagnosed with cancer. You get diagnosed with COVID. Then there's the strikes. In terms of keeping the momentum for yourself, physically, mentally, emotionally, staying true to this arc, to these characters, to their story over five years while you're going through the wringer, how do you do it?

Well, it's a good question, and I don't know exactly the answer. Something that pops into my mind is just momentum. We were off for two years, and you come back and you see all the same people and it feels like you just had a long weekend. You pick up where you left off, like muscle memory or something. That was fascinating to go through that experience. But talk about who you're coming back to: Amy Brenneman and John Lithgow and Alia Shawkat, it's a wonderful team. That makes all the difference.

You talk about coming back and picking up where you left off, but you've been through something truly life-changing. You had a very, very intense health scare with cancer and then Covid. How does that change your approach to the work that you're doing, and to the relationships you have on and off set?

Going through something like that exacerbates lots of stuff. Your philosophy of life, what's your strategy now, here, in this situation? You bring out everything that's ever worked for you in your life. A lot of that has to do with the L word, love. That corny thing.

You realize how much you love your family, how much you love the nurses and the doctors who are there for you trying to get you better. And you feel all your loved ones, you feel their love. All of that is quite intense. It's interesting that everybody goes through it, I think, differently. Not only the people who are going through the illness, but the people who love you. Each one of them is going through it in their unique way.

I remember my doctor saying to me, "Jeff, you're not fighting. You've got to fight." I had no idea what they were talking about. I was in surrender mode. I say, "Oh, people. That's right. People die. This is me doing that. Oh, okay, well what's this like?"

Do you feel there's a difference between fighting and surrendering, because you can surrender to the process in a very constructive way?

Absolutely. You can also surrender to fighting in a funny sort of way. They blend. It's like the particle and wave thing, quantum computing. That seems to be what life is about, it's a big paradoxical thing.

When you talk about love, you got a trainer so you could walk your daughter down the aisle?

As soon as I got out of the hospital, I had a trainer and I would have these little goals. The first goal was, let's see how long you can stand, "...89, 90. 90 seconds, good, good." Then you walk around the hospital floor and you've got your oxygen. You've got the thing up your nose and the pursed lips breathing. That's a wonderful skill that pursed lips breathing. I still do that.

Just to get yourself to the toilet, it's a good day.

That's a toughie, right? Defecating, oh my God. So I gave myself these little goals and I didn't think I was going to work again. "No, Jeff, if you live, you're not going to be able to do that." And then my daughter Hayley was getting married and she said, "Come on, dad, walk me down the aisle." This is an interesting thing about fighting and surrendering, surrendering to the idea of walking her down the aisle. That's what I was into. It was difficult. We go up to our edge where we think, "This is far," and then I like to do little experiments on myself. I say, "This is my edge. Wonder what would happen if I just go a little farther?" To reach that edge is a wonderful thing. That's where all the gold is really. That's where the treasure is, when you can mess around with that edge and see where it is.

So the day came and I said, "Gee, I can do it. I can walk her down the aisle." Then I was walking her down the aisle and then the dance, "You think you've got enough to dance with your girl?" I said, "Well, let's see. I'll give it a shot," and surrendered to it. It is difficult, I raced back to my chair, put the [oxygen] thing on. But after that I said, "Maybe I'll be able to go back and fire up 'The Old Man' again."

And I did. Zach, my trainer, worked with me to do that. He was so skillful at just enough challenges. But let me do that in my own speed. I appreciated that.

When you've been through all of those things, it gives new context to this character that you're playing, to be able to own that phrase, "the old man." How does that feel for you to be the old man?

Well, I qualify, 74 now, but Joel Grey, he trumped us all in his 90s. John Lithgow is older than me. But being an old man, fascinating thing. Having gone through that illness and stuff, one of the things that occurred to me is this doesn't go on forever. You're going to end. You've got some stuff to do. Now's the time, man. That's what this age has given me. It's like, "You got some stuff? Let's see it. Let's hear it."

And you've been doing this for basically 74 years, right? You started as a baby.

Six months old.

You come from a show business family: your father Lloyd Bridges, your mother Dorothy Bridges, and your brother Beau Bridges. Yet you've said you weren't sure you wanted to go into this profession. What made you change your mind?

Unlike a lot of showbiz parents, my parents dug showbiz a lot and wanted all their kids to get into it. That was the atmosphere I grew up in, and what teenager wants to do what their parents wanted them to do? So I resisted. I had a lot of reasons for my resistance, I didn't want to compete with my father and my brother. I was interested in music and painting and a lot of other creative endeavors. My dad said, "Jeff, don't be ridiculous. That's what's so wonderful about acting. All those interests? You're going to be called upon to use them in the work." I'm glad I listened to him. He was absolutely right. Now, as an older guy, a lot of those desires that were pushed down when I was a kid are kind of coming up now.

I grew up with The Beatles and Bob Dylan, and [there's] nothing like getting a band together. Like my dad told me, "You're going to be asked to do some of these things." And "Crazy Heart" came along and my dear friend T Bone Burnett was doing the music. After the success of that, I thought, "Gee, I've got all these other tunes. Maybe I'll call up T Bone to see if he wants to get these done." So we made an album. And I said, "Yeah, I've got all these great musicians that live in Santa Barbara." And my dear friend Chris Pelonis, he's a wonderful musician, we formed a band called The Abiders. Then I got sick, then the strikes, and there was all this downtime.

What I found coming up for me was, "Gee, Jeff, you've got all of these tunes in your music mine," [that's what] I call it. "Why don't you go in there and see if there's anything there that you want to realize?" I found a whole slew of songs, and I didn't feel like getting a band together and rehearsing. I'd say, "Just put this rough stuff out and juxtapose it to some interesting images that you shoot on your cell phone." I put out five volumes of that adventure called "Emergent Behavior," and if people are interested they can check it out on my website.

That's one of the things that has popped up, like saying, "Come on old man, what you got? Now's the time. You're going to wait until everything is perfectly polished? No, if somebody else wants to do that in the future, they can polish them up. Just put out what you got."

I'm also a photographer. My wife's a photographer, and we've been married 47 years. For our wedding, she gave me the gift of a Widelux camera. There was a fellow, Mark Hanauer, who came to our wedding and took some pictures and I said, "Wow, what kind of camera is this?" The format's kind of like a 70 mm movie format. My wife gave me one of these, and I started taking pictures during the movies that I was making and made books for the cast and crew of these pictures, and put out a couple of books that are available to the public.

Then I was upset because the camera was no longer being made. The factory burned down about 30 years ago. So I got this idea and started to talk to Sue. We got in cahoots with some Germans, Charys and Marwan, and we are remaking this camera. I can go on and on, I've got all these little side projects, it's fascinating. So, that's what old age is doing to me. It's funny.

The Dude has become an institution and a way of life for people. I want to ask you about that because you lean into it. You are happy to be The Dude, you are happy to be The Dude for other people. What has he meant to you in terms of your life and your identity over the last 26 years?

Oh yeah, gosh. Working with the brothers, that's the top. The Coen brothers and the team that they assembled, a lot of them have worked together many, many times. The experience itself was wonderful. I got my Widelux, and took a bunch of pictures. If I want to relive those times, I can just look at them. Then "Lebowski" has bloomed in all these different ways. I mean, there are these Lebowski Fests. I had my Beatles moment playing with my band, The Abiders, at a Lebowski Fest, playing to a sea of dudes. They're all dressed up like The Dude or bowling pins or whatever. That was wonderful.

Then I'm having a dinner. I think it was Ram Dass, it was his birthday. Ram Dass is sitting to my right and to my left is a guy named Bernie Glassman, who happened to be a Zen master. He had an organization called the Zen Peacemakers. And he leans over to me and says, "Jeff, I want to let you know I really enjoy 'The Big Lebowski.' It's filled with Koans, and I'm all about bringing Buddhism to these days that we are living now." I said, "Koan, what do you mean?" He says, "Well, look who wrote and directed the movie, the Coen brothers. And the movie is filled with Koans."

You know what a Koan is? "What's the sound of one hand clapping?" These mind challenges.

I said, "Well, what do you mean?" He says, "Well, first of all, 'The Dude abides.' That's very Buddhistic." Both of our favorites was, "Yeah, but that's just your opinion, man." "Shut the f__k up, Donnie. That's a good Koan." He says, "Let's write a book about it." So that's what we did. We went up to Montana, I got a place up there for two weeks. We wrote "The Dude and the Zen Master," and it's a wonderful book.

Later, Bernie came to visit when we were doing "True Grit," and he asked the [Coen] brothers, "Are you guys into Zen?" They said, "No, no, no, no." When making "Lebowski," we never talked anything spiritual or philosophical. But that movie has bloomed in beautiful, beautiful ways.

The Dude made a special cameo on a certain Zoom call this summer. Why was that important for you? You are a political guy, you are outspoken. You care a lot about things like childhood hunger and the environment. What are the stakes in this election, and why did you want to be involved in that?

Life is so serendipitous. I was invited to White Dudes for Harris. I qualify so beautifully for all those things, particularly The Dude deal. That's what really drew me to it. Another example of "Lebowski's" blooms. I got on there and I didn't really realize it was a more serious thing, that it was white dudes. I still don't quite get it, are we not respected or something? What is the thing? Do you know?

As a non-dude, maybe I shouldn't.

I don't really understand about the white guys thing for Harris, but I'm certainly in support of Kamala. My gosh, she's wonderful. Loved her the other night on that debate. And we got all the support from Taylor Swift and the Cheneys. Liz Cheney is such a wonderful hero, I think, to all of us. It's exciting.